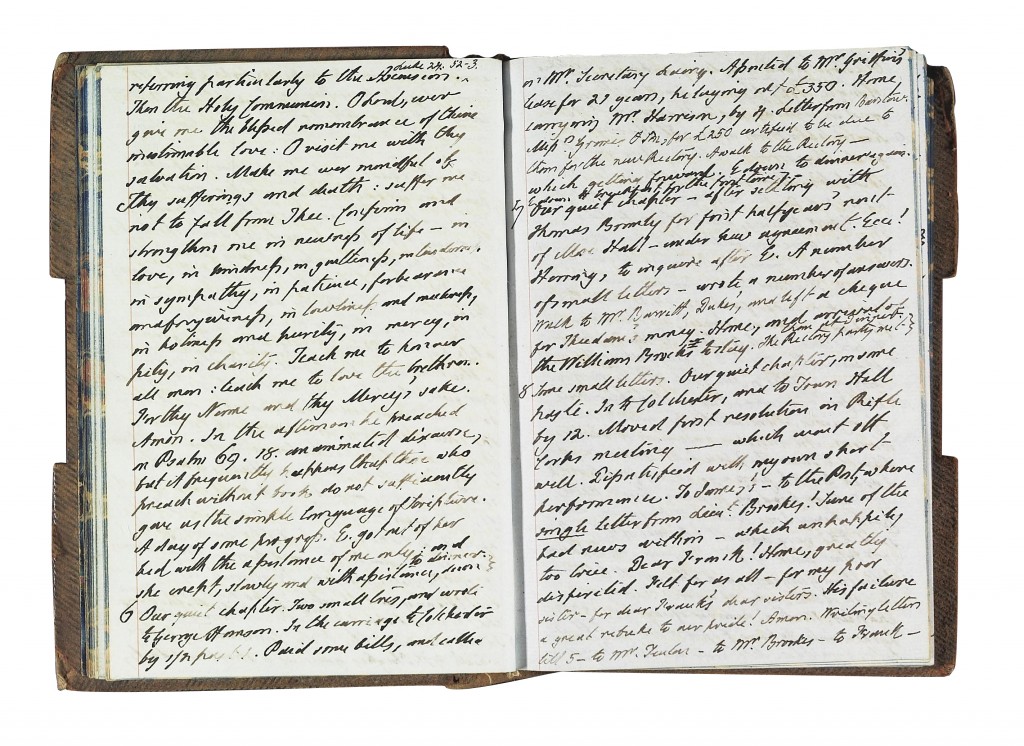

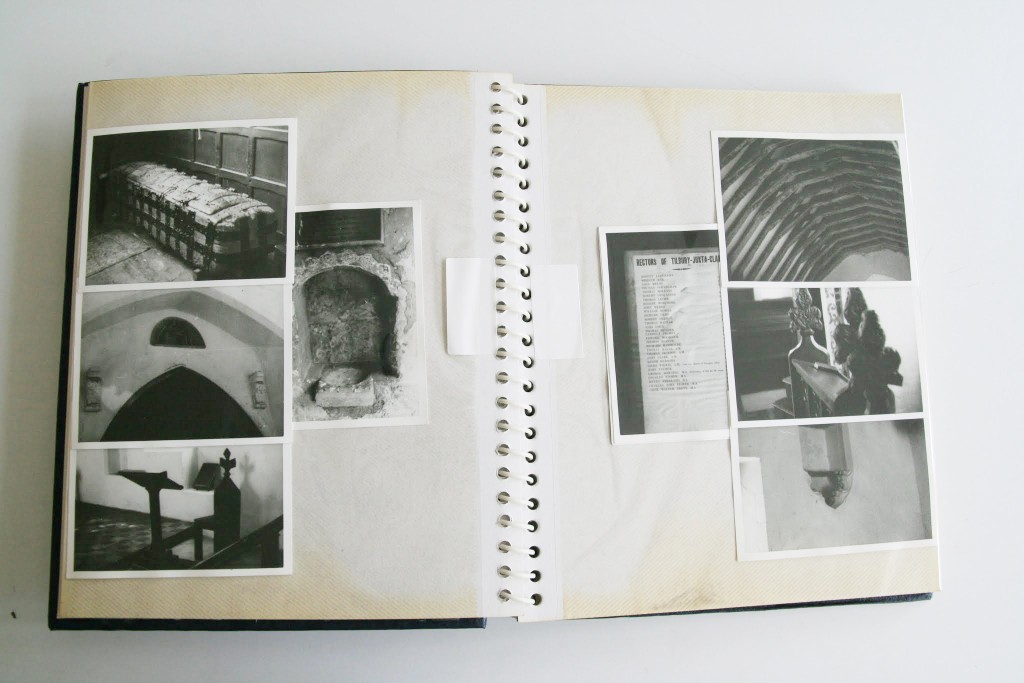

Back in May, our Senior Conservator Tony King visited the Deepstore facility in Cheshire. Here he writes for us about what he found there…

During a recent visit to Flintshire Record Office I was lucky enough to accompany some of their staff on a visit to the Deepstore Records Management Facility which has found a radical solution to the problem of finding space to store ever expanding archives.

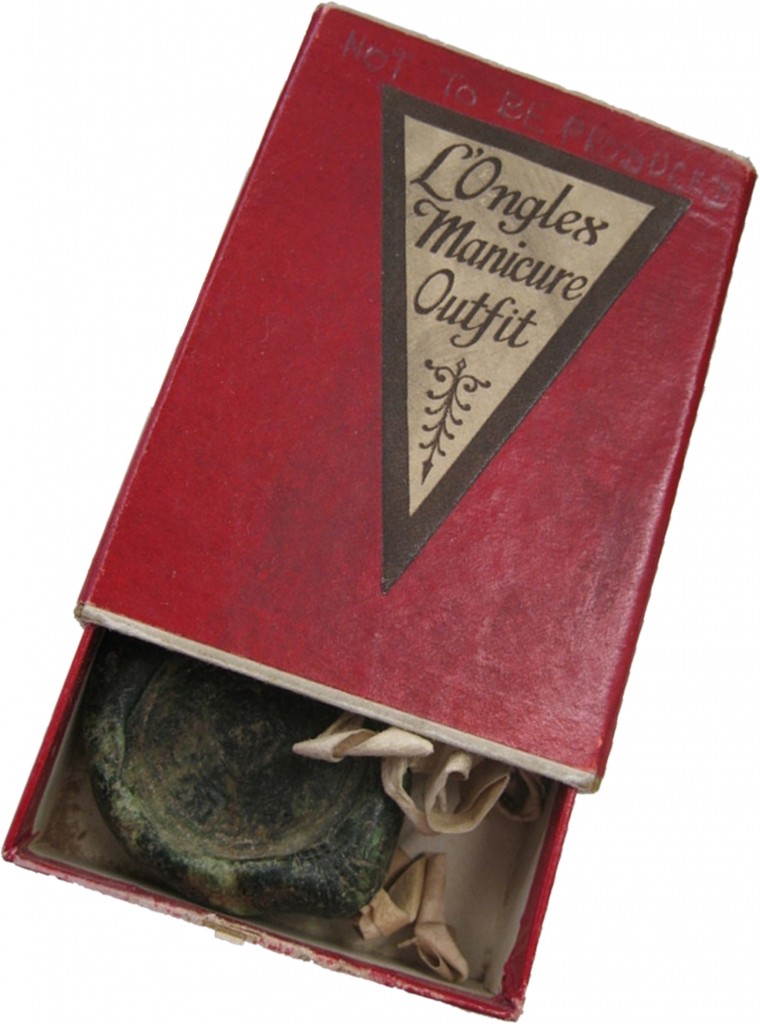

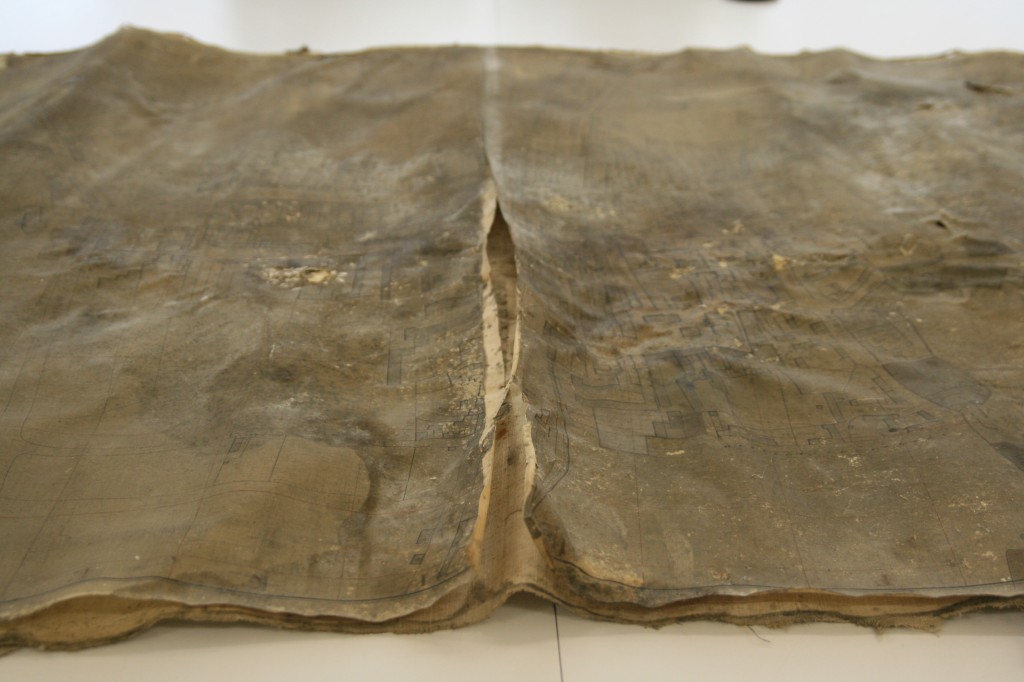

600 feet below the town of Winsford in Cheshire lies a 200 million cubic metre underground salt mine, one corner of which has been turned into a storage facility used by many organisations to house their archives. Opened in 1844, this working salt mine provides salt for treating icy roads but has made use of the practically unlimited space that results from the mining process to generate an income that is less weather dependant!

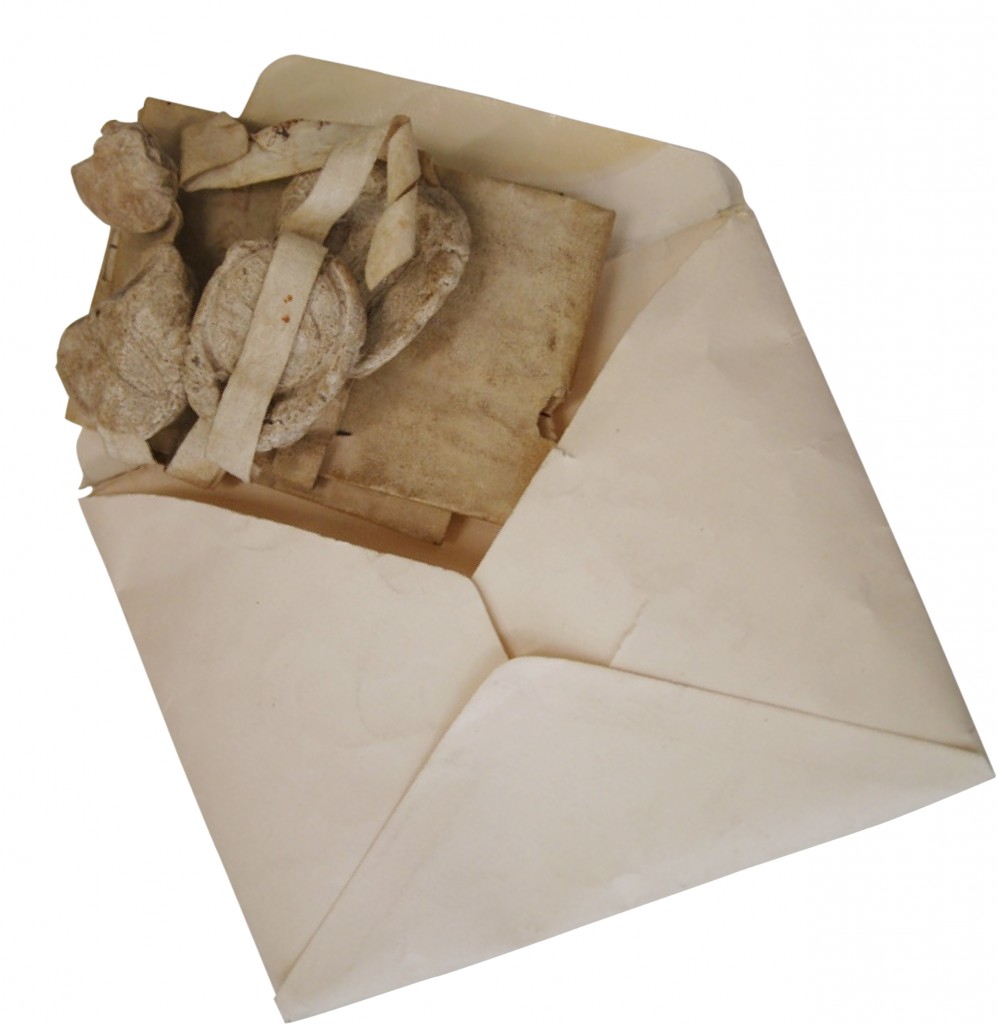

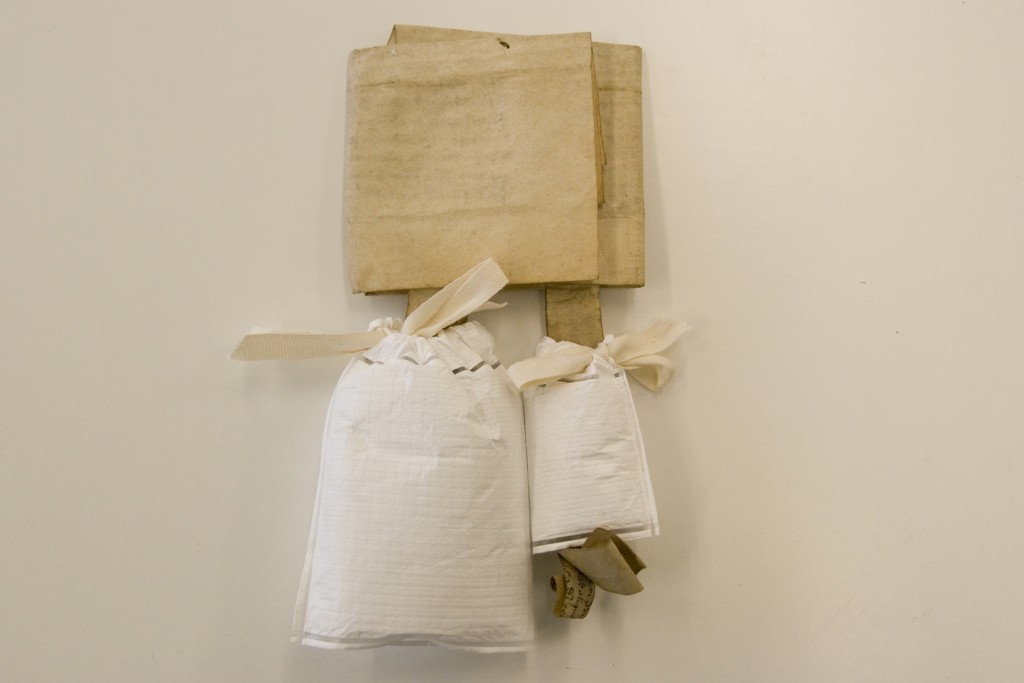

It may seem a bit drastic to store historically important and irreplaceable records in a working mine but many aspects of the way a salt mine is run and the conditions inside make it suitable for long-term archival storage. Temperature and humidity levels are very stable at around 14 degrees centigrade and a natural relative humidity of around 65% that can be brought down to 50% by dehumidifiers, achieving the conditions recommended for storage of archival material. The image of mines being wet places prone to drips and floods does not apply here; on leaving the access lift down which pallets full of boxed documents come daily the mine feels dry without a hint of damp.

A little distance from the lift is a large document reception area where the boxes are entered into the database and then taken to one of the numerous units constructed further along the mine. On entering a unit it feels remarkably like any other repository or strong room with boxes neatly arranged on the shelves that fill the 7-8 metre high rooms. The air in each unit is carefully monitored to maintain correct temperature and humidity as well as to check for smoke particles that may indicate a fire starting. As a working mine (the working face is many miles away from the storage areas) strict rules on air quality, security and fire response all apply which is something that benefits the material stored there.

National institutions such as The National Archives as well as many County Record Offices and libraries keep a proportion of their holdings at the site and along with banks, legal firms, police authorities etc. contribute towards the 1.9 million boxes of items currently stored down this mine. Although Essex Record Office currently has no plans to use a facility like this, it was fascinating to visit the site and the fact that many organisations have already moved documents to the mine shows that these sort of arrangements are likely to become increasingly common.

![IMG_0970[3]](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/IMG_09703-1024x648.jpg)

![IMG_0664[2]](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/IMG_06642-1024x648.jpg)

![IMG_0797[1]](http://www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/IMG_07971-985x1024.jpg)