University of Essex MA student Grace Benham reflects on her placement spent working on a collection of oral history interviews tracing the history of women’s refuges in Essex. You can read her previous blog posts here.

Uncovering the hidden history of Women’s Refuges in Essex has been as rewarding as it has been difficult. The struggle of the women, and men, who fought to recognise the importance of protecting women from abusive histories, though tragic in its need, is incredibly inspiring.

In my academic history background, I have rarely delved into feminist history, and especially British feminist history, which surprises most as I have also been an outspoken advocate for women. This choice is rooted in two fundamental reasons: firstly, it is difficult to see the hatred and vile attitudes towards women that existed not so long ago which the matriarchs of my family would have grown up with, and it is hard to reconcile that with the privileges we hold today. But, more than this, I had never seen myself as a very ‘good’ feminist; in my younger years I failed to recognise nuance and my own privileges. But an important lesson from those who have dedicated decades of their lives for others is that, despite differences, unity for the common good is absolutely more important.

Tackling this collection was daunting to say the least. My own personal experience with abuse in a romantic relationship which had motivated the selection of this collection also made going through this material hard. However, the hidden histories of Women’s Refuges also provides a wealth of hope in the selfless willingness to help those who need it and to fight for everything they’ve got.

The oral history collection, ‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’, comprises stories from Colchester, Chelmsford, Ipswich, Grays, and Basildon and the women who worked, lived, and fought for refuges from domestic abuse (the interviews pertaining to London were beyond the remit of this placement). All stories which, although containing some collaboration and inspiration, tell of formidable and dedicated women who, born from the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s, took it upon themselves to fight for Women’s Refuges in a time when domestic abuse was not taken seriously at all, let alone seriously enough.

For an example of such strength and sacrifice, one should only look to Moyna Barnham MBE, who in her interview tells of how she would go alone in the middle of the night to collect ‘battered women’, having to go up against the abusers, such a dangerous role that one night her husband even followed her to ensure her safety. Such bravery is to of course be commended, but it is also unfortunate that the police and local welfare workers were not there for these women, and it was up to independent volunteers to provide such a service.

I also believe that such a study has come at an unfortunately poignant time as the tragic rise of people, particularly women, seeking help with domestic abuse during the lockdown period of COVID-19 paints a painful picture of the persistence of the problem. It is also important in such discourse to recognise nuance. In Alison Inman’s interview, a key figure at both Basildon and Colchester Refuges, she describes how society expects a ‘perfect victim’ of domestic abuse, i.e. an innocent and naïve woman. However the reality is that domestic abuse occurs in every gender, every sexuality, every class, and every age; it is a universal problem. I feel that the current COVID-19 domestic abuse discourse highlights this problem and its nuances. A recent BBC Panorama investigation revealed not only the scale:

‘Panorama has found in the first seven weeks of UK lockdown someone called police for help about domestic abuse every 30 seconds – that’s both female and male victims.’

BBC PANORAMA PROGRAMME BROADCAST 17 AUGUST 2020

But this investigation also showed a lacklustre government response that should not belong to a society that has, apparently, been acknowledging this problem since the 1970s.

‘It took the Westminster government 19 days after imposing restrictions to announce a social media campaign to encourage people to report domestic abuse, as well as an extra £2m for domestic abuse helplines.’

BBC PANORAMA, 17 AUGUST 2020

Of course the lockdown was an unprecedented event that, hopefully, exists in isolation, but surely such a demonstration of the terror in some people’s homes shows in undeniable terms that domestic abuse and violence remain problems, and the services and education addressing the problem are underfunded and underrepresented. Therefore, what we can glean from this oral history collection is an invaluable educational resource on how to combat domestic abuse, and to be inspired by those who came before us.

This truly has been a transformative experience, both personally and as a historian, and I would like to extend my warmest thanks to the Friends of Historic Essex for their funding of the project.

Sources:

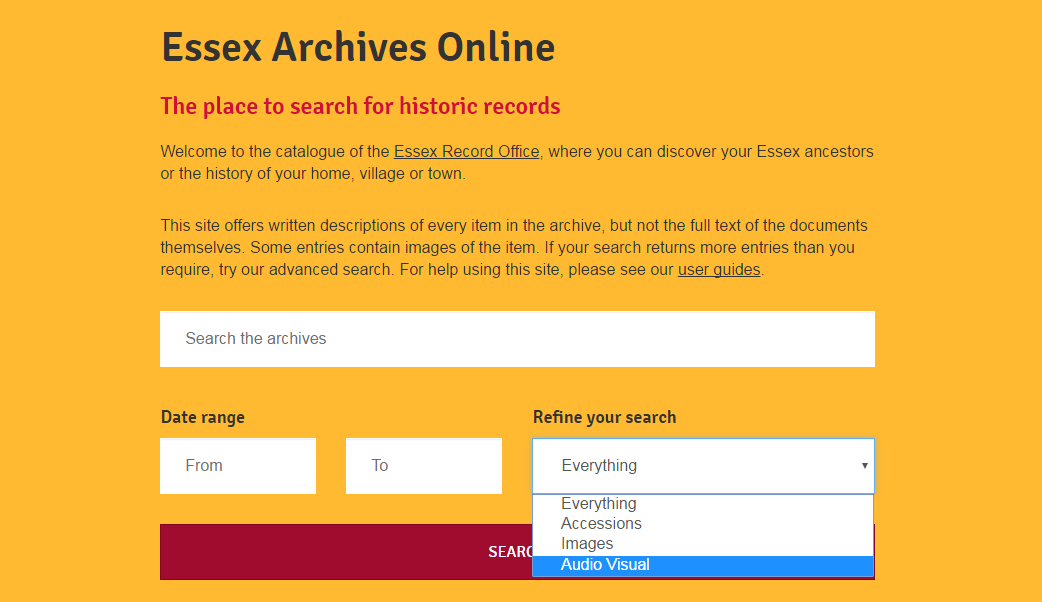

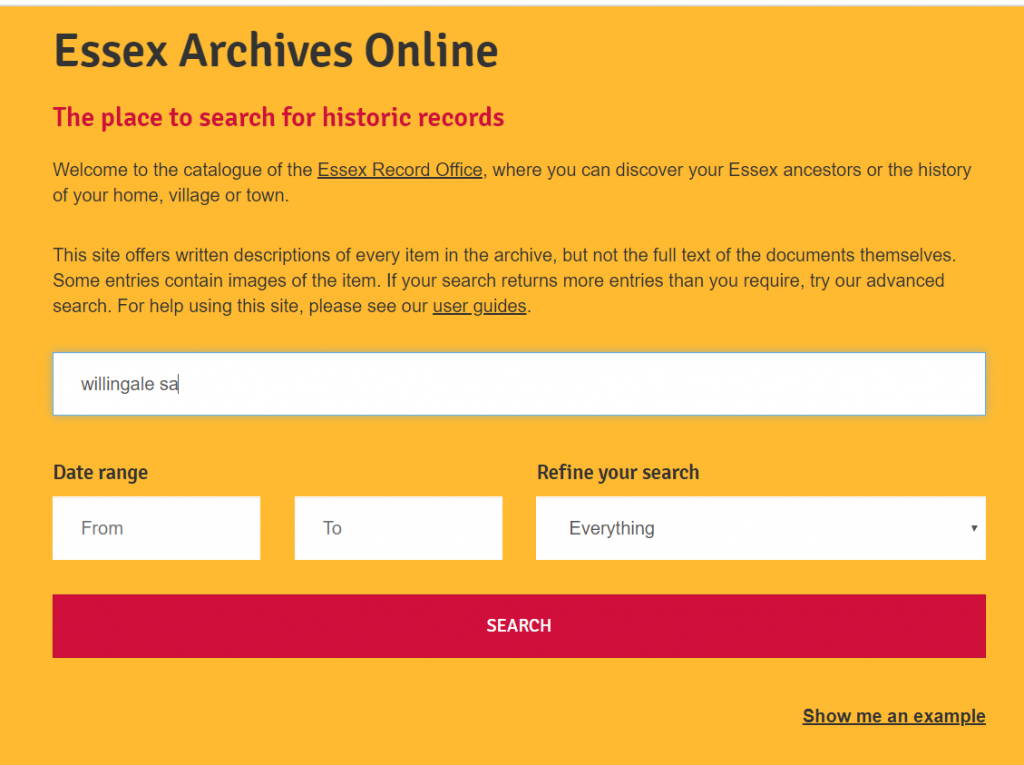

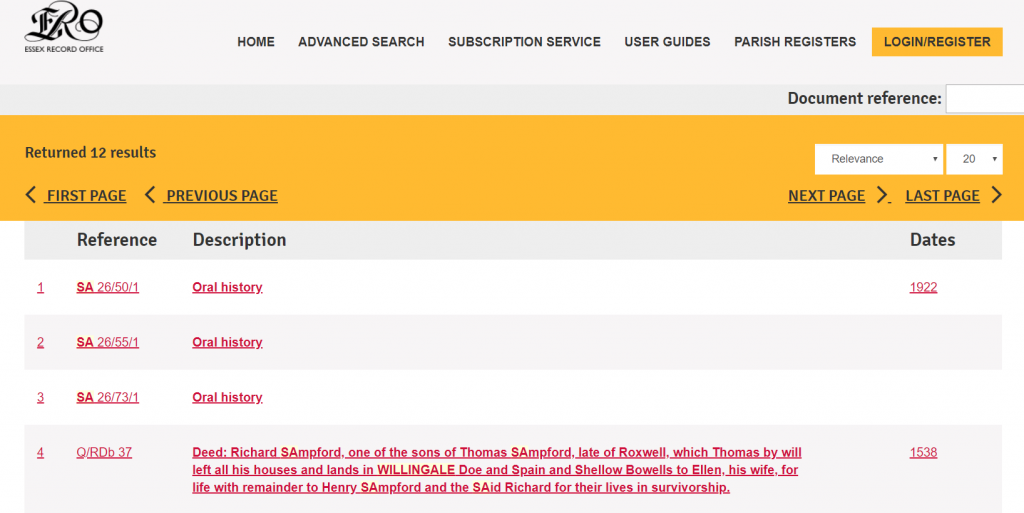

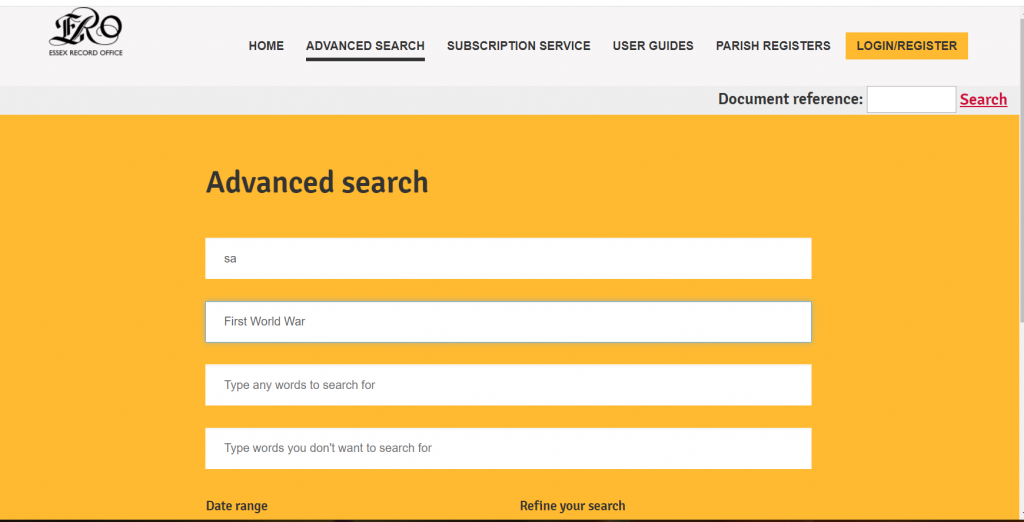

‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’ collection of oral history interviews in the Essex Record Office (Acc. SA853)

BBC Panorama report on domestic abuse during lockdown, published 17 August 2020

If you need support to deal with Domestic Abuse, please call the helpline below or check out the following guidance.

National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Local support: https://www.essex.gov.uk/report-abuse-or-neglect/domestic-abuse

COVID-19 Domestic Violence Guidance: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-and-domestic-abuse

He spoke to a variety of inmates about their experiences, their first impressions, their hopes for the future. As to be expected, different people had different responses: some created home out of their cells, some did not want to personalise their cells in any way, but just focus on getting to their home outside. Some found it an extremely trying ordeal; some survived by finding humour in the bleak situation.

He spoke to a variety of inmates about their experiences, their first impressions, their hopes for the future. As to be expected, different people had different responses: some created home out of their cells, some did not want to personalise their cells in any way, but just focus on getting to their home outside. Some found it an extremely trying ordeal; some survived by finding humour in the bleak situation.