First of all, apologies for the break in transmission. We have been having some technical problems which our IT department is working on solving, and hopefully all will be back to normal soon.

On 1 April this year we published news of a recent ‘discovery’ in our archives that showed that medieval Chelmsford had its own John Lewis department store. The document in question said that a man named John Lewis had bought some land in Chelmsford fronting the High Street to build ‘a big shop’.

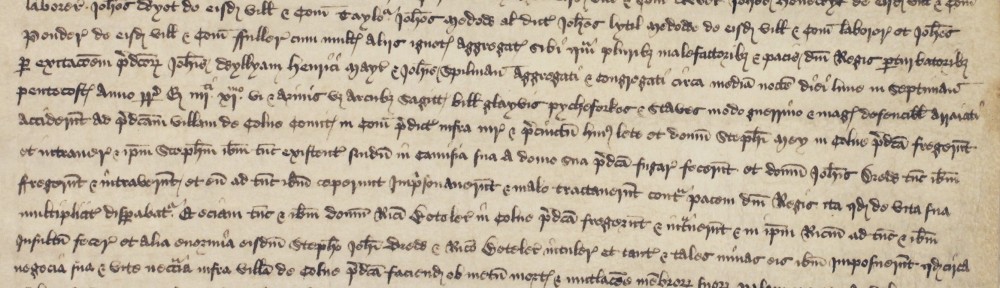

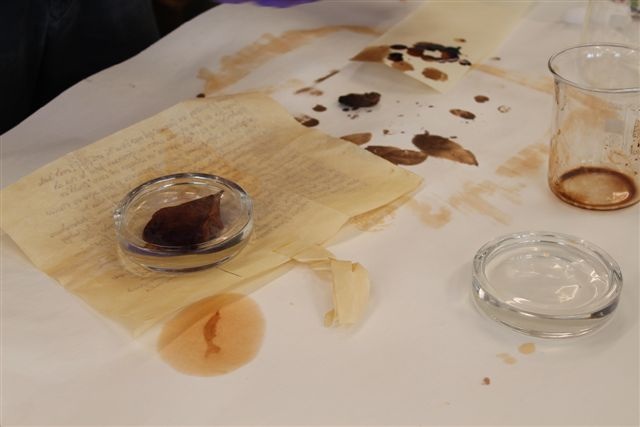

The text for the fake deed was constructed by Archivist Katharine Schofield, who specialises in medieval documents. She used her expertise to mimic the way in which medieval deeds were written, constructing it in both Latin and in English translation. The finished text was sent to our Conservation Studio, where Conservator Diane Taylor used her calligraphy skills to recreate the style in which a deed of this type would have been written.

Here we reveal what was right and what not quite so right about our April Fools forgery…

A question of language

Medieval legal documents were written in Latin, unless there was no Latin equivalent for an English word, when the scribe would have to resort to the vernacular to make the meaning clear. (See, for example, our post on ‘Names not to call the bailiff’, when the Maldon court had to break away from Latin to record the insults in question in the vernacular English.)

By the date of our forged deed (1405), however, English would have been much more commonly used and expressing something in Latin would have consequently been much more difficult.

Location location location

Field names do occur in deeds of this date (and earlier) and they are often obviously of a pre-Conquest origin. The land mentioned in this deed, ‘Le Backsydes’, is taken from the description of land on the Walker map of 1591.

Purpose

Our forgery tells the reader the purpose the land was being given for, i.e. the building of a ‘big shop’. Real deeds of this date, however, do not mention the purpose for which the land is being conveyed. (Moreover the idea of department stores was still some way off!)

Money matters

In our deed, the annual rent that John Lewis paid for his land was one chilli pepper on All Fools Day.

Token rents were quite common in deeds of this date and applied to land that had been bought and sold as well as to land that was leased. Rents could be flowers, items of clothing such as gloves, pepper and wax. Some of these would be of a monetary value, others would not. Chilli peppers, however, are native to the America sand were not introduced to Europe until the end of the 15th century.

Payment of rents was usually done on feast days, the most common in medieval deeds being Easter, Midsummer, Michaelmas and Christmas. Occasionally there were payments on feast days. However, All Fools Day is not a feast day.

Witnesses

The witnesses in our deed were chosen from the names of founders of stores which now all trade as John Lewis round the country. A number had to be discarded as the Christian names were 19th century and would not work in Latin. There was, for example, a third Cole brother but his first name was Skelton.

The land in question in our deed was being granted by the Bishop of London, who would have had his own men who would have been witnesses to his deeds and would not have necessarily had to call on men from outside his own diocese.

Our witnesses from Watford and Chelsea may well have been called upon as they were part of the Diocese of London, but our witnesses from Reading and Windsor(part of the Diocese of Salisbury) and Cambridge and Norwich(Diocese of Ely) would not have been.

We also gave our witnesses both first names and surnames and places of origin, but at this date witnesses were more often described by their first names only, e.g. Robert of Cambridge, or by a family relationship, e.g. Robert son of John. Since they would have been regular witnesses and known to the Bishop and his household no more accuracy was required. It is for this reason that medieval deeds usually conclude the list of witnesses with ‘et multis aliis’ (and many others). The deed was describing an act which had taken place, the transfer of land (hence it was written in the past tense) and the witnesses were people who would if called upon be prepared to bear witness to the transaction. It was unnecessary to list them in lengthy detail, it was sufficient to know that witnesses existed.

What’s in a date?

The date of 1st April in 1263 was Easter Day. It is very unlikely that any deed would be dated on Easter Day. Both Sunday and Easter Day were too holy for business to be transacted on those days. Deeds are often dated before or after Easter and are often dated by the number of days from Easter. It is also rare for deeds of the 13th century to be precisely dated. Dates can often be deduced from other evidence and sometimes if the witnesses are well known.