As the nights draw in it’s the perfect time to gather to hear tales of dark happenings in the past. Here, bestselling novelist Syd Moore tells us about how she first became interested in researching Essex witches, ahead of her talk at our screening of Witchfinder General on Friday 26 October 2018 – find all the details here.

Best-selling novelist Syd Moore who will be speaking about her research into Essex witches at ERO

I first encountered Sarah Moore, when I visited the pub in Leigh on Sea named after her. It was shortly after it had opened and the name piqued my curiosity. This was mainly because a) we share the same surname and b) in my experience it’s unusual to come across a pub named after someone who isn’t famous or a king, queen, lord, lady, duke, admiral, marquis etc. When I asked about it at the bar the staff told me the brewery chain that owned the place often ran competitions to name their pubs. Regularly they would chose winners with a local flavour. Sarah Moore, I was informed, was the subject of a Leigh legend – an evil sea-witch who raised the Great Storm of the Estuary, caused great havoc about the town and sank a plethora of boats. When I probed further I learned the story of Sarah Moore. Which, if any of you don’t know, goes like this:

Sarah Moore was a bent and bitter old witch, who made her living sitting by the estuary down in Old Leigh, telling fortunes and selling sailors ‘a good wind’ for a penny. The latter was a common practice along various coasts. The ‘witch’ would take a length of string or ribbon and ‘tie’ the wind into it. The sailor would buy it. Then when out at sea, if they desired wind, they would untie the string. A single knot would loosen a breeze, two would summon a strong wind, and three would unleash a storm. Allegedly one day, a foreign captain rocked up in Leigh. He was a zealous man and, when he heard about Moore and her spells, he forbade his crew to consult her, give her any money or buy any wind. As the legend goes, when Moore heard about this she flew into a rage and, in revenge, summoned up The Great Storm of the Estuary. This, she threw at the vessel as it sailed out into the open sea. The poor boat rocked from side to side, with all aboard much afeared. The crew tried with all their might to get the sails down but, alas, the rigging kept snaring. One of them cried out in a moment of awful horror, ‘This is the work of the witch. It’s the witch!’ Whereupon, the story goes, the captain picked up an axe, ran to the mast and felled it with three hefty strokes. As soon as the mast hit the deck the storm instantly subsided. When the beleaguered crew got the wounded ship back to Belle Wharf, they saw, there on the floor the dead body of Sarah Moore, three axe wounds across her corpse.

This was a splendid tale, I thought at the time, full of intrigue, horror, suspense and supernatural murder. And as soon as I heard it my interest was immediately fired up. But I was left full of questions: was the story really a myth or a legend? Had Sarah Moore been a real person? Was there some truth in parts of it? Any of it?

In a strange synchronicity, at about the same time, I was asked to present a pilot for a TV series about legend and lore of the land. Cunningly I suggested we look at Sarah Moore and, microphone in hand, ventured out with the team to quiz a whole host of strangers about the legendary sea-witch. I heard variations of the tale many times, but nobody really knew whether Sarah had ever existed. A couple of Leigh locals suggested it was possible that the myth had been stitched together from various Essex witch stories and that Sarah was a conflation of sorts. It wasn’t what I had been expecting to hear, to be honest. And although I was disappointed I determined to keep on going with my own private research. Which I did. And over the next few years I delved deeper into the myths and legends of Leigh and its surrounding areas, and read up on local history. Yet I did not find much else about the witch.

Until one day when my friend, the writer Rachel Lichtenstein, invited me to go with her to the Essex Record Office. Believe it or not it hadn’t dawned on me that I might be able to find out more about Sarah outside of history books. Neither was I aware that anyone could pop along to the offices. Somehow I had it in my head that it was something you could do only if you were a professional researcher or a historian or historic writer or had some other kind of credentials. So the whole trip really was a bit of a revelation.

That afternoon spent at the Record Office I discovered the numerous resources: books, reports, various antique volumes, microfiche. With great excitement I dived straight in to see what I could find. It took me several visits but one dark and stormy afternoon, almost as I was about to give I up, I hit upon a record!

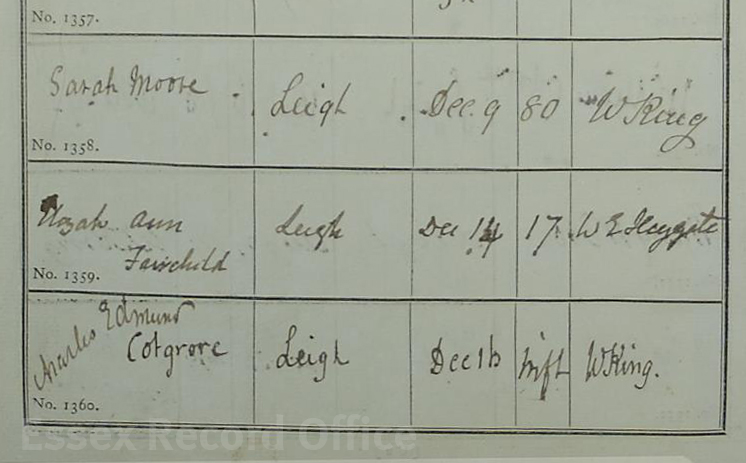

Burial record for Sarah Moore at St Clements church, Leigh-on-Sea, 14 December 1867 (D/P 284/1/38 image 87)

This was the burial entry in the St Clement’s church register for one Sarah Moore. It was dated the 9th of December, 1867 and was my ‘light bulb’ moment. I remember sitting in the record office as the rain pelted against the windows and feeling flooded with light. For not only did the record confirm my hunch that Sarah had been a living breathing woman, it also gave me a solid date around which to research. Another thought that immediately struck me was the fact she had died in 1867. The Great Storm of the Estuary had occurred in 1870. Sarah couldn’t possibly have been responsible for raising it, even if you did believe poor dispossessed old women had control over meteorology. She had been dead for three years. This realisation prompted me to conclude that Sarah had been scapegoated for the event posthumously. During my further research I was to learn that this was not the only natural disaster that had been attributed to her. All of this evoked a tremendous amount of pity for the woman, and despite the centuries that separated us, I felt outrage on her behalf. The feeling spurred me on to explore the real woman behind the myth and to tell her untold side of the story.

Soon I found her on the census of 1851, by which time she had been twice widowed and left with a great number of children to provide for. In fact, Moore had a terrible life. Perversely over the years, her association with witchcraft and tragedy, metamorphosed her reputation into a ‘wicked’ one. Through careful consideration I was able to track the route that had facilitated the switch from tragic victim to sinister oppressor and highlight this in the novel, that was published in 2011, The Drowning Pool. It was the start of a career investigating the other miscarriages of justice that occurred in our county: the Essex Witch Hunts.

If you would like to hear more about them I will be speaking on the 26th of October at the Record Office, before a screening of the very relevant classic horror film The Witchfinder General.

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the

Ahead of his talk at ERO as part of the