Lawrence Barker, Archivist

(A14439, part)

The document of the month for June is the first volume of a two-volume publication entitled Psalmodia Evangelica, ‘a complete set of psalm and hymn tunes for public worship’, published in St Paul’s Churchyard, London by Thomas Williams of Clerkenwell Green in about 1789. It is a charming volume of psalm and hymn tunes which opens a window into protestant and non-conformist worship at the time of Jane Austen. The volume once belonged to Stebbing Independent Chapel (later Congregational Church), one of three music books we took into our custody at the beginning of April this year. Presumably, it was used in the worship of that church.

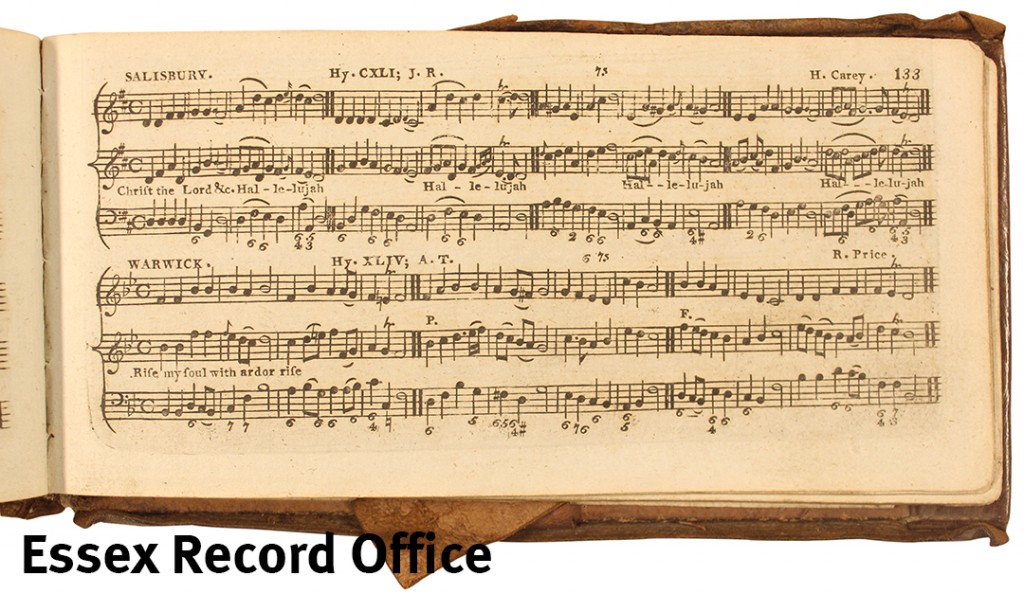

The title page proudly claims that it contains ‘a greater number and variety than any former collection’. There are some tunes which worshipers today would instantly recognise; such as ‘Salisbury’, the tune named by Wesley himself for his Easter Hymn Christ the Lord is Risen today, Hallelujah, or ‘Helmsley’, Lo he comes with clouds descending. But there are many more which have since fallen out of use.

Interestingly, the music is ‘correctly adapted for three voices [instead of the usual four found in hymn books today], and figured for the organ’; the main tune is in the middle, with a contra part on top harmonising above and below the melody and a figured bass below.

“Figured bass” is a common feature of eighteen century instrumental music, where the “continuo” part played by ‘cello, bass and bassoon, would also be played on an organ or harpsichord with chords above, indicated by figures under the part rather in the manner of guitar chords indicated in a popular song today. For example, where there is no number, a standard chord with the root note at the bottom would be played, whereas a 6 indicates a chord “in first inversion” with the third note at the bottom and the root note on top, i.e. six notes above the bass.

At the beginning of the volume, there is an introduction which offers a guide to performance expressed in language both redolent of the period and seemingly indicative of a non-conformist preoccupation with improvement. It begins:

Most people are sensible of the difference between a regular and just performance of Psalmody in divine worship, & that confusion and dissonance too often heard instead of it; though few, comparatively, will bestow any share of their own time & attention to apply a remedy…Should those who have already learned to sing condescend to look over these pages, it is not impossible that many of them may be either informed of reminded of some things tending to their improvement.

The Psalmodia includes advice for singers, including, crucially, remembering which part they are singing

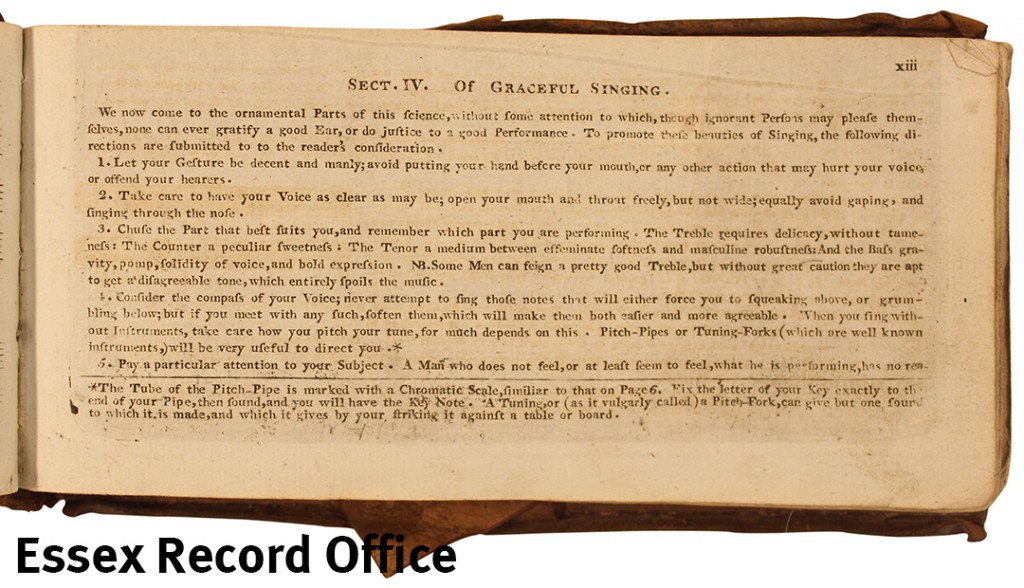

For example, in section 4, OF GRACEFUL SINGING, ‘the following directions are submitted to the reader’s consideration’.

1) ‘Let your gesture be decent and manly;’ which seems to point to an all-male choir made up of men and boy trebles.

3) ‘Chuse the Part that best suits you…The Treble requires delicacy, without tameness: The counter a peculiar sweetness: The Tenor a medium between effeminate softness and masculine robustness: And the Bass gravity, pomp, solidity of voice, and bold expression.’

6) ‘Express your words with all the politeness possible, without affectation; imitate the Orator rather than the Clown.’

The Psalmodia will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout June 2016.