We never seem far from an election these days, so it seemed a good opportunity to compare today’s elections with one that took place in Essex over 250 years ago in 1734.

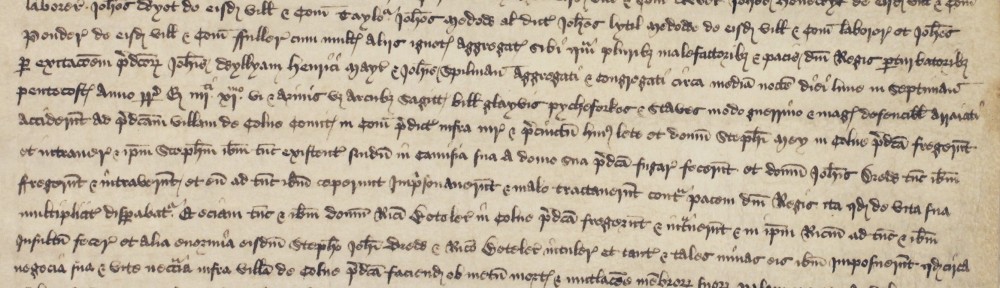

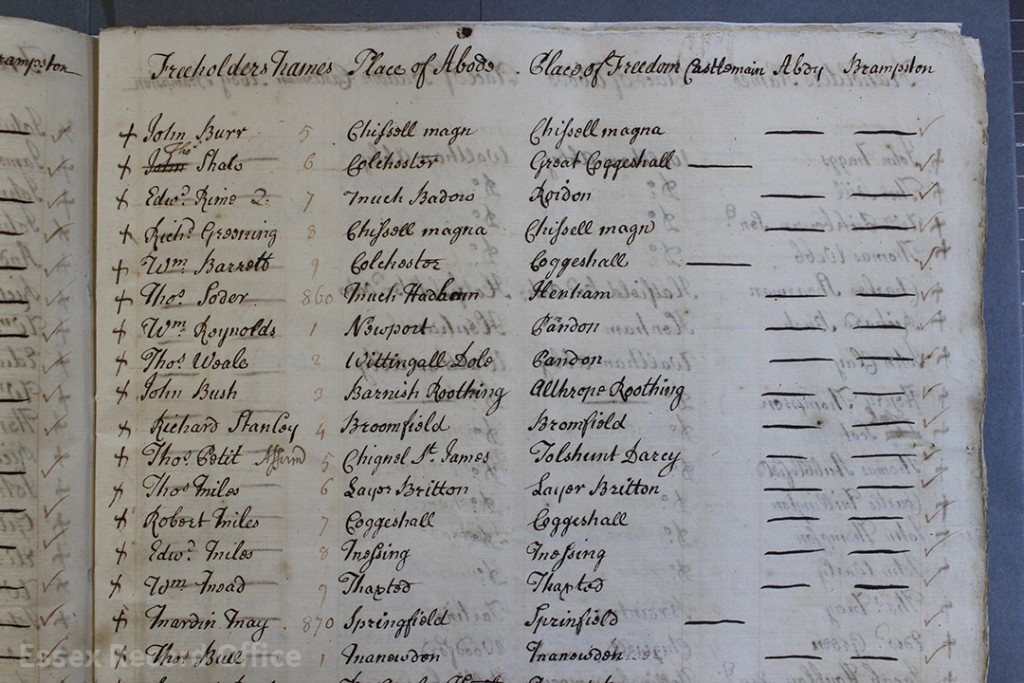

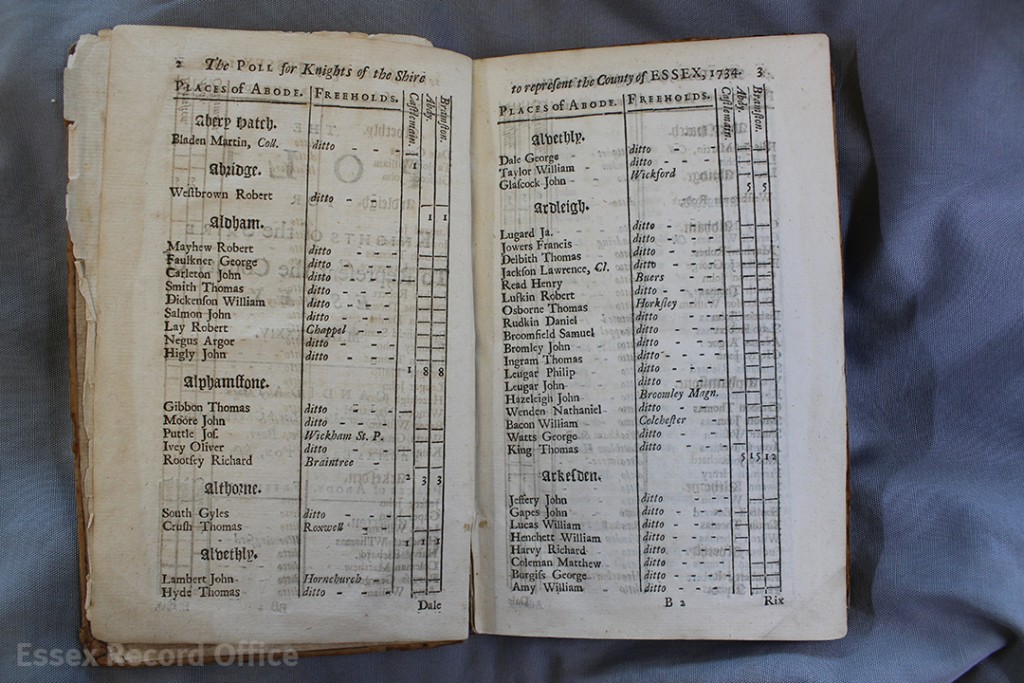

This month’s document (D/DU 3053/1) is a rare survival. It looks to be the original working draft of the poll of 1734 used by the Sheriff, Champion Bramfill, to record the votes cast by electors. The electors’ names are recorded along with where they lived and where they held property that qualified them to vote in Chelmsford, and the votes that they cast. The list does not appear to be in any order, suggesting that what we see is the order in which electors appeared in Chelmsford to vote. Their actual votes can be seen recorded in columns on the right.

A page from the 1734 poll book (D/DU 3052/1). Electors seem to be recorded in the order they turned up to vote. Their name is recorded, along with where they lived, where they held land that qualified them to vote in Chelmsford, and the votes that they cast.

There is not much about the 1734 election that we would recognise today as a free and democratic election. Only a small proportion of the population was entitled to vote; electors had to be male, and had to own property of a certain value. The Reform Acts of the nineteenth century gradually extended voting rights but it was not until 1928 that all men and women aged over 21 were entitled to vote.

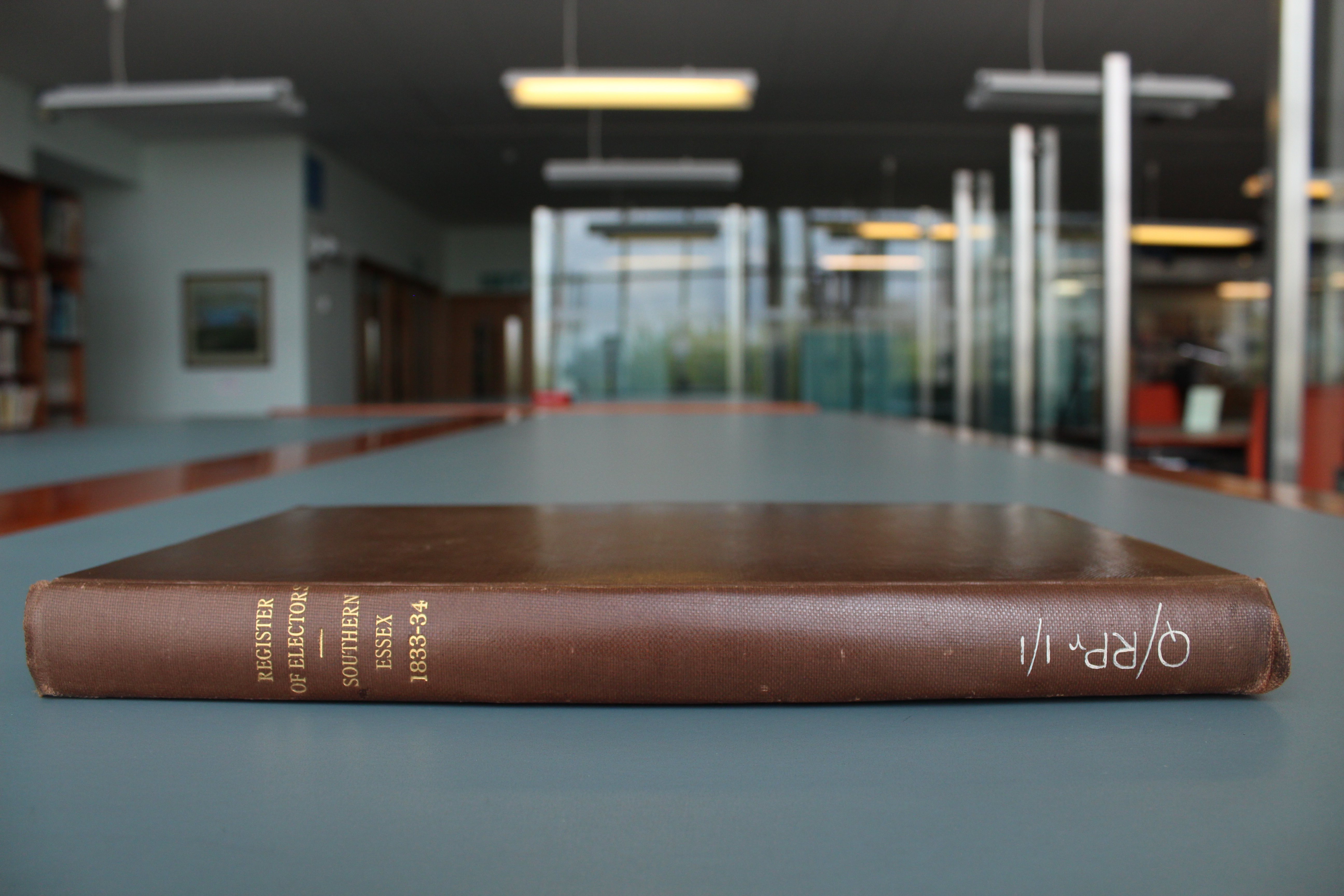

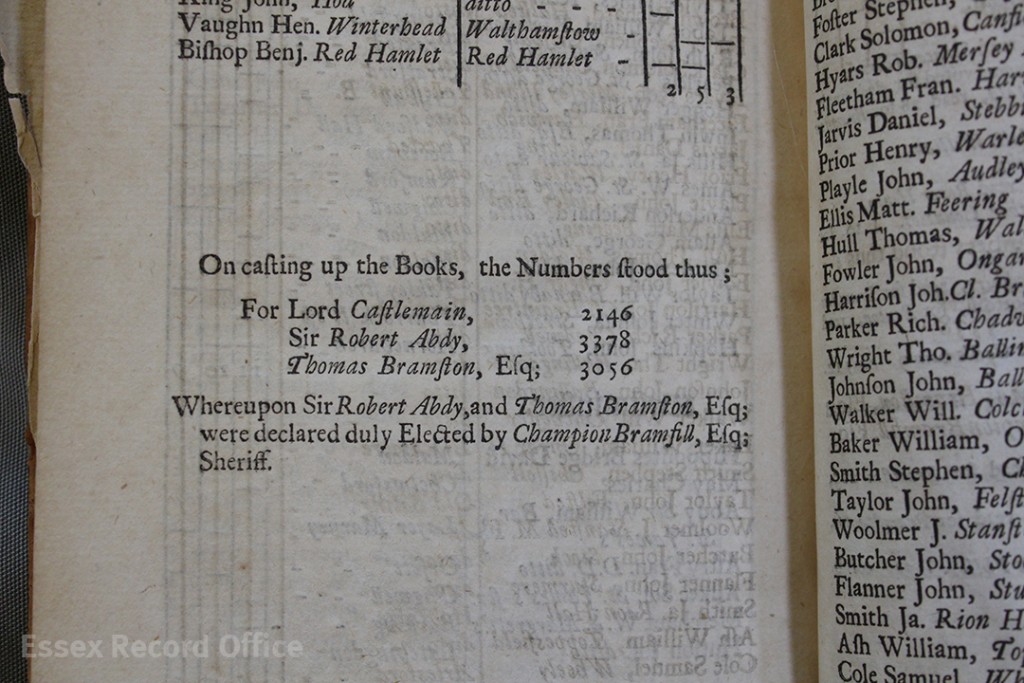

The secret ballot was not introduced until 1872, and the votes cast were published in a printed book (we have a copy catalogued as LIB/POL 1/5).

The published version of the poll book, which showed who each elector voted for (LIB/POL 1/5).

At the time, two “Knights of the Shire” as they were termed, represented Essex in Parliament (the Boroughs such as Maldon and Colchester also had their own representatives). Voters were entitled to cast two votes, and had three candidates to choose from; Lord Castlemain was a member of the Whig faction, while Thomas Bramston and Sir Robert Abdy were both Tories.

Both seats were taken by the Tories (Castlemain received 2,146 votes, Abdy 3,378 and Bramston 3,056). This was contrary to the national trend, during the period known as the ‘Whig supremacy’ between 1715 and 1760.

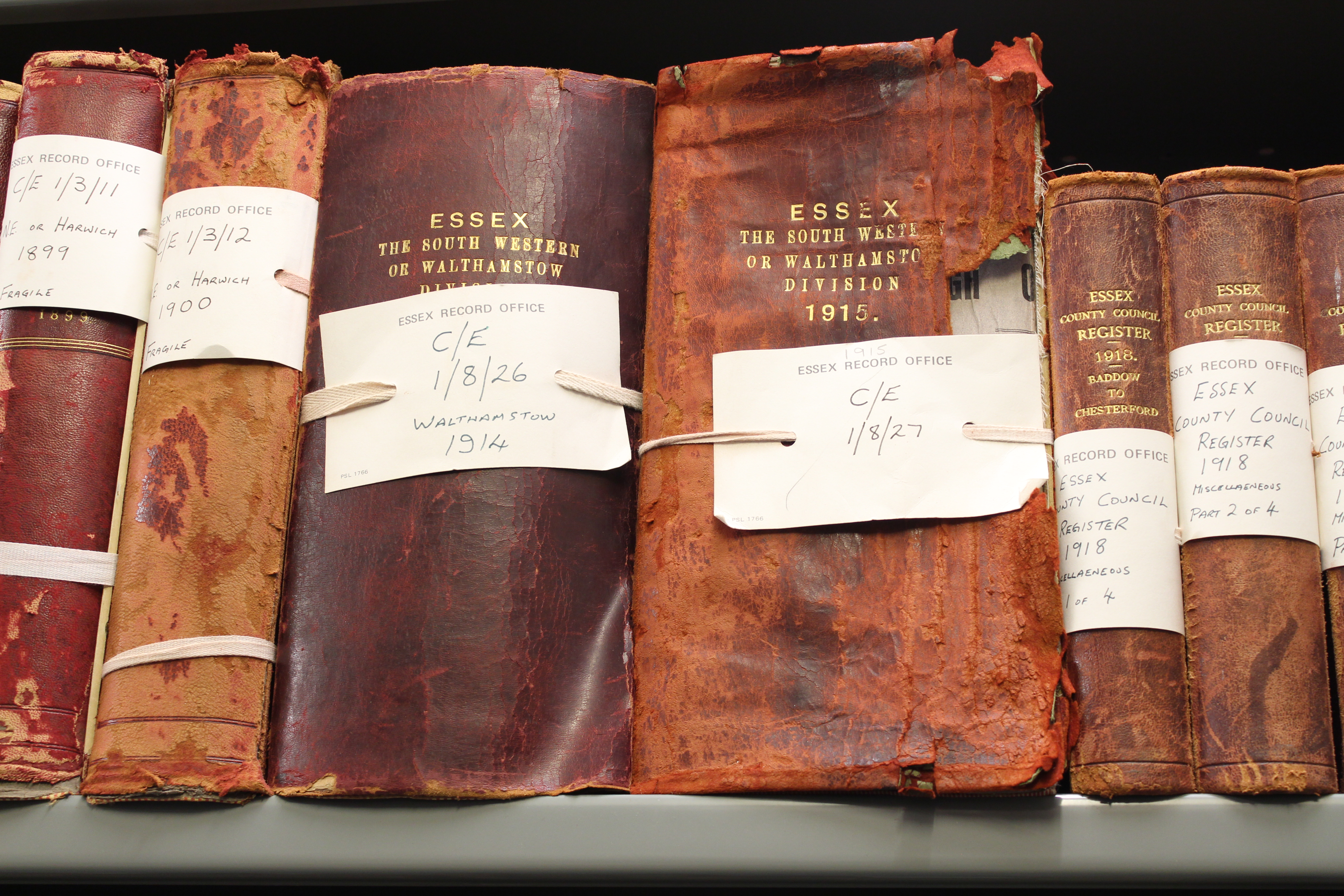

The results of the election at the end of the published version of the poll book (LIB/POL 1/5)

The terms ‘whig’ and ‘tory’ were originally terms of abuse coined during the Exclusion Bill Crisis of 1678-81 (‘whig’ comes from ‘wiggamore’, a Scots term meaning cattle-driver, and ‘tory’ from the Irish ‘torai’, meaning outlaw or robber). As Charles II’s reign drew to a close, the whigs were worried about his Catholic brother James II inheriting the throne. Catholicism was associated with the absolutist style of rule of the French Catholic monarchy, and whigs favoured a constitutional monarchy, with the monarch ruling in conjunction with parliament. Tories, on the other hand, thought that parliament had no business meddling with the line of succession.

James II did inherit the throne on the death of Charles II in 1685, but he did not last long. He was pushed out of power in 1688 in the ‘Glorious Revolution’, and replaced with his daughter Mary II and her husband William of Orange (William was also her first cousin and James’s nephew). For the next few decades rebels known as Jacobites (from the Latin for James, Jacobus) attempted to restore James II and his heirs to the throne.

Both tory candidates in Essex in the 1734 election were Jacobites, and had key roles in an uprising that was planned to take place in February 1744. James II’s grandson Charles (known as the Young Pretender or Bonnie Prince Charlie) was to lead an invasion supported by the French army, landing at Maldon. Thomas Bramston was slated to be one of the leaders of the uprising in Essex, and was described to the French government as a ‘gentilhomme d’un grand crédit dans la province d’Essex où les troupes doivent débarquer’ (a gentleman of great standing in the county of Essex where the troops will land). Sir Robert Abdy was one of six tory MPs who knew the military details of the scheme, and was referred to by the Pretender himself as one of his principal advisers in England.

In the end the planned invasion did not materialise; a storm scattered the ships which would have carried the troops across the channel, and the government got wind of the conspiracy. Bonnie Prince Charlie landed in Scotland instead in 1745, a campaign that ended in brutal defeat at the Battle of Culloden.

The poll book will be on display in the Searchroom throughout June 2017.