Please Note: This blog post contains potentially upsetting material that may not be suitable for all.

Our University of Essex placement student Grace Benham reviews some themes emerging from her work on the ‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’ oral history project about the founding of women’s refuges in Essex and London. Read her first blog post here.

In September 1976, after years of domestic abuse, Maurice Wells shot his wife Suzanne dead and held his daughter hostage in the ensuing siege of his home in Colchester. In February 1977 he was sentenced to manslaughter and served a ten-year sentence. Chris Graves, a solicitor who aided Colchester Refuge in its inception, credits the outraged reaction to such a short sentence to his own involvement, and the refuge movement as a whole.

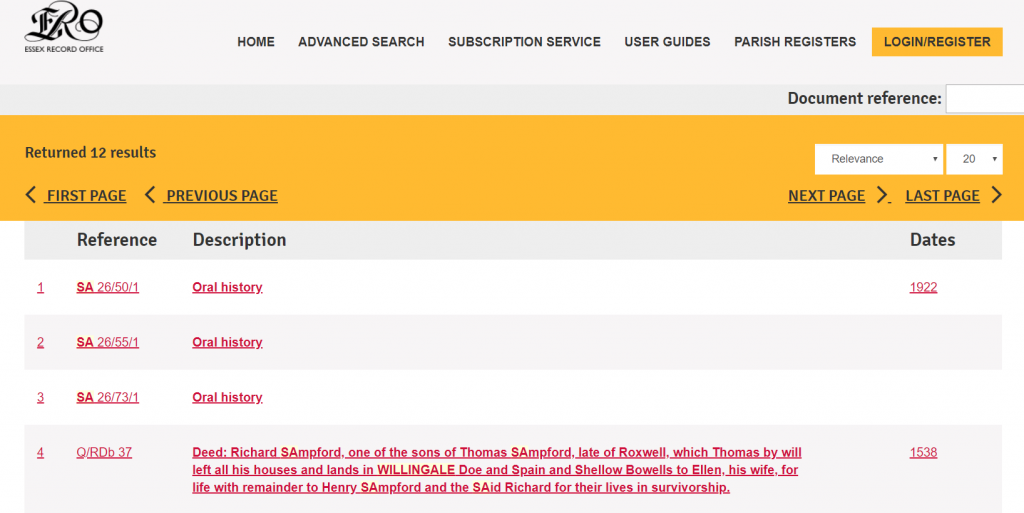

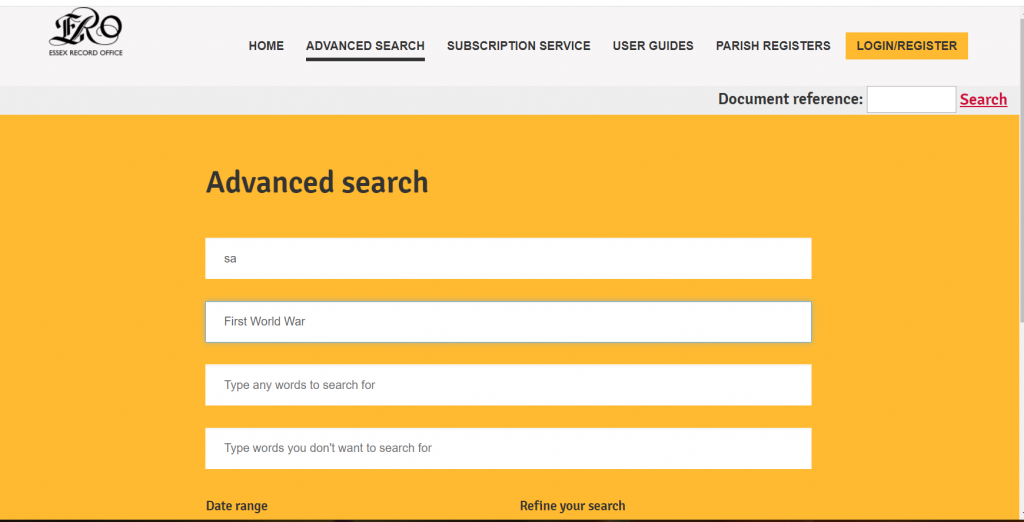

Colchester Refuge had been in the works previous to this case. Many of the interviewees recorded for the ‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’ project (Acc. SA853) explained how the refuge was born out of the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s, which had come over from America and gained its own life in Britain. However, the Wells case, a case which myself and everyone else I have discussed this with have never heard of, highlights an important theme of both the past and the present, the privatisation of domestic violence. According to the Daily Gazette, once out of prison Wells went on to commit crimes against children and told his victims that if they reported him, he could kill them like he killed his wife.

This story is one of many featured on the ‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’ website and one of many that are unheard amongst the general public. Domestic violence is, generally, an inherently private crime as it occurs within private spheres, but the issue goes beyond just this. The prevalence of domestic violence, which only became properly acknowledged in the 1970s following the Women’s Liberation movement, created uncomfortable questions, shame and denial. It could be easy to dismiss domestic violence because it occurred ‘behind closed doors’. Alison Inman recalls a story in which a local authority in Essex refused to set up a refuge because ‘they didn’t have domestic violence within their borough’, which led to an increase in women from that area entering neighbouring refuges.

Moreover, the women who needed refuges and would go on to become residents typically were those of lower classes due to the fact that those with available resources would have other options to avoid going into a refuge. This builds a stereotype of a certain type of woman who suffered domestic violence, even though this is a problem that affects all classes, all races, all genders, all sexualities. Such women could be demonised for their choices as they had little to no one defending them. These women could also be silenced through the normalisation of violence in working class marriages. Normalisation occurred through popular culture, such as the Andy Capp comics that featured in the Daily Mirror from 1957 to 1965, which regularly portrayed domestic violence as not only humorous but as a normal and acceptable way to treat one’s wife, particularly within working class marriages.

Another facet of this conversation that has slowed bringing the issue of domestic violence the time, energy and funding it deserves are the elements of shame and denial which are intrinsically linked. Rachel Wallace, who addresses domestic violence and humour, in particular in regard to Andy Capp, makes excellent observations on how humour is used in a response to shame. She depicts how these comics would not have been a success without an audience. In validating a taboo subject that is, unfortunately, rife in our society, such an audience finds themselves validated and vindicated, and therefore the shame is diminished. Much like denial, humour is used as a defence against shame, and it is hard to argue that those who were indifferent to domestic violence would find humour in such situations. We can see examples of this use of humour within this oral history collection, with councillors joking about how their wives treat them in response to being petitioned for refuges, with change only coming, according to Moyna Barnham, when the law required councils to provide homes for ‘battered women’, a burden councils did not typically want to bear.

The future of refuges and reform around the handling of domestic violence situations require us to recognise the lessons of the past, and the need for education and recognising nuance. I had the great honour of attending a talk regarding a project titled ‘Sisters Doing it for Themselves’ , a collaborative project by the Women’s Refuge Centre and the London School of Economics. For this project, leading figures of the women’s volunteer sector in London are interviewed by schoolchildren, to not only teach oral history practices to a younger generation and collate such vital histories but also in order for both parties to learn something from the other. The main points of this talk resonated with these interviews that occurred in 2016 and 2017 regarding women’s refuges in the East of England, in that there is an emphasis going forward on education and nuance, both of which were crucial in the first founding of women’s refuges. To confront the denial, shame, blame and stereotypes around domestic violence is surely only a step in the right direction.

We are grateful to the Friends of Historic Essex and the University of Essex for their financial support in making this placement possible.

Additional Resources

Wallace, Rachel. 2018. ‘”She’s Punch Drunk!!”: Humor, Domestic Violence, and the British Working Class in Andy Capp Cartoons, 1957–65.’ Journal of Popular Culture 51 (1): 129–51. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12646.

‘Sisters Doing it for Themselves’ project website

‘You Can’t Beat a Woman’ project website

Daily Gazette newspaper article about Maurice Wells

Newspaper report in The Times on the Maurice Wells case.

If you need support to deal with domestic abuse, please call the helpline below or check out the following guidance.

National Domestic Abuse Helpline: 0808 2000 247

Local support: https://www.essex.gov.uk/report-abuse-or-neglect/domestic-abuse

COVID-19 Domestic Violence Guidance: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-and-domestic-abuse

He spoke to a variety of inmates about their experiences, their first impressions, their hopes for the future. As to be expected, different people had different responses: some created home out of their cells, some did not want to personalise their cells in any way, but just focus on getting to their home outside. Some found it an extremely trying ordeal; some survived by finding humour in the bleak situation.

He spoke to a variety of inmates about their experiences, their first impressions, their hopes for the future. As to be expected, different people had different responses: some created home out of their cells, some did not want to personalise their cells in any way, but just focus on getting to their home outside. Some found it an extremely trying ordeal; some survived by finding humour in the bleak situation.