Have you visited any of our listening benches, installed as part of our Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place? Recently Jade Hunter, a PhD student studying Geography at Queen Mary University of London, embarked on a mini tour of some of the benches to learn more about them. She shares her thoughts on her visits in a guest blog post below.

I’m currently studying for a PhD in Geography and I encountered the listening benches when writing an assignment on sound projects. My research interests lie in identity and place, specifically in Essex, so I was really keen to visit and experience benches in different locations.

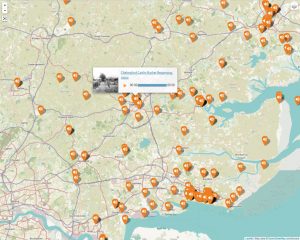

I planned to visit a number of benches which I thought could demonstrate the breadth of Essex as a large, and diverse county. I work in London, and one of the things I’m always struck by is how far away people think Essex is when they live within the (blurring) city boundaries. Visiting the benches highlighted the relationship which parts of Essex have to the city. Audio at the Raphael Park bench suggests that Essex might act as ‘the lungs of London’, and the soundscapes at the Romford, Hadleigh and Chelmsford benches include birdsong, traffic and the sounds of trains delivering people from the suburbs into the city. Viewed from the bench in Hadleigh Park, Canvey Island rooftops were flanked by a ship sailing to the London Gateway super-port, showing a connectedness not just to London, but further afield.

View from the listening bench in Hadleigh Country Park. Copyright Jade Hunter.

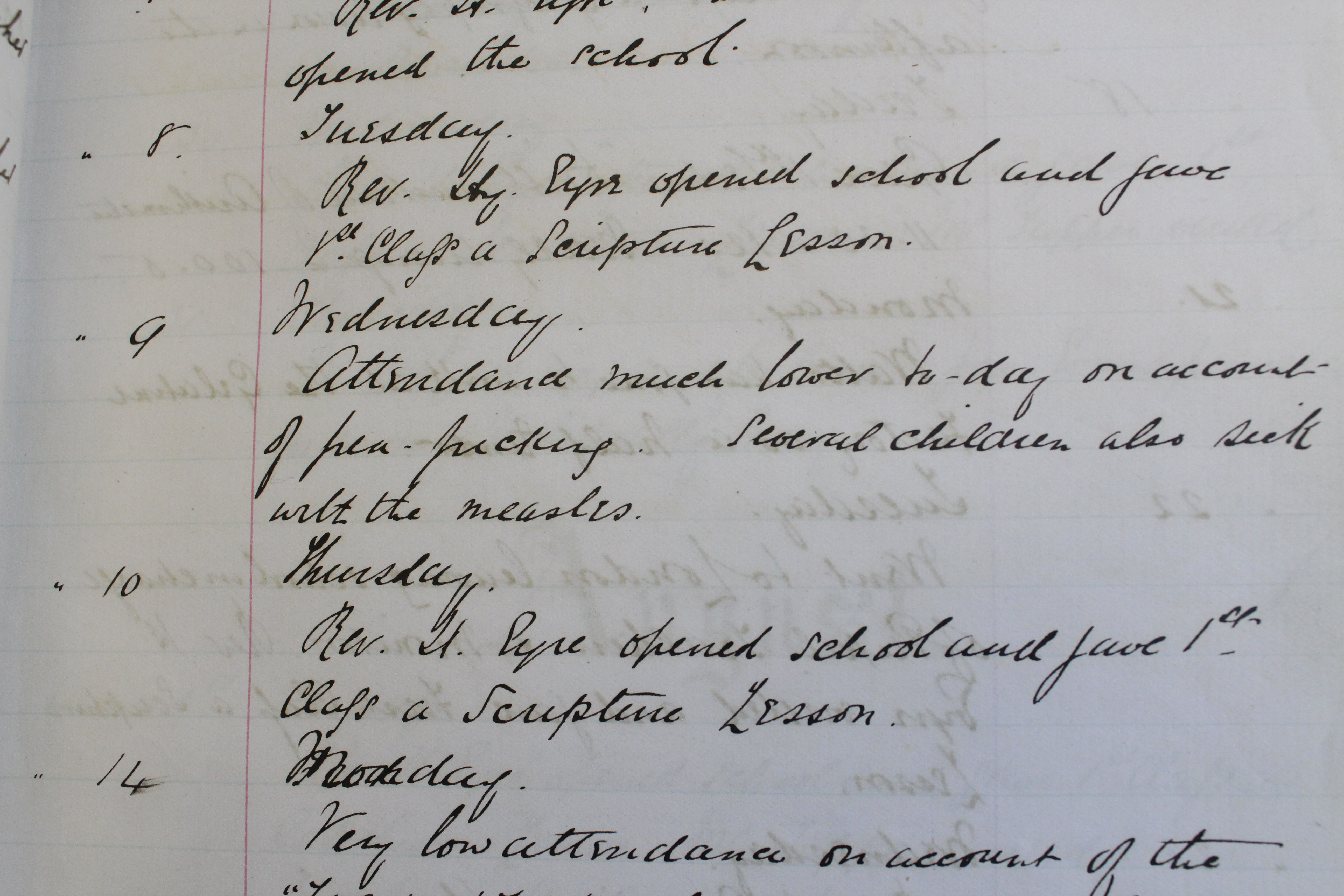

I was interested to hear about the history of the bench locations – listening to villagers of times past speak about specificities of life in Kelvedon, for example.

Frank Hume and Ronald Hayward describe their memories of the Crab and Winkle railway line that ran through Kelvedon, a clip from an oral history interview used on the Kelvedon listening bench (SA 44/1/25/1).

But I was most drawn to benches with audio about experiences which could be more broadly shared, in locations where it is perhaps more likely that people from across and outside the county would visit too. Perched on a hillside, the Hadleigh bench plays radio clips describing picnics and walks across the park. Feeling connected to the speaker and landscape, I shared the views they described of the estuary and Canvey Island below. This overlap creates connections across experiences, across time.

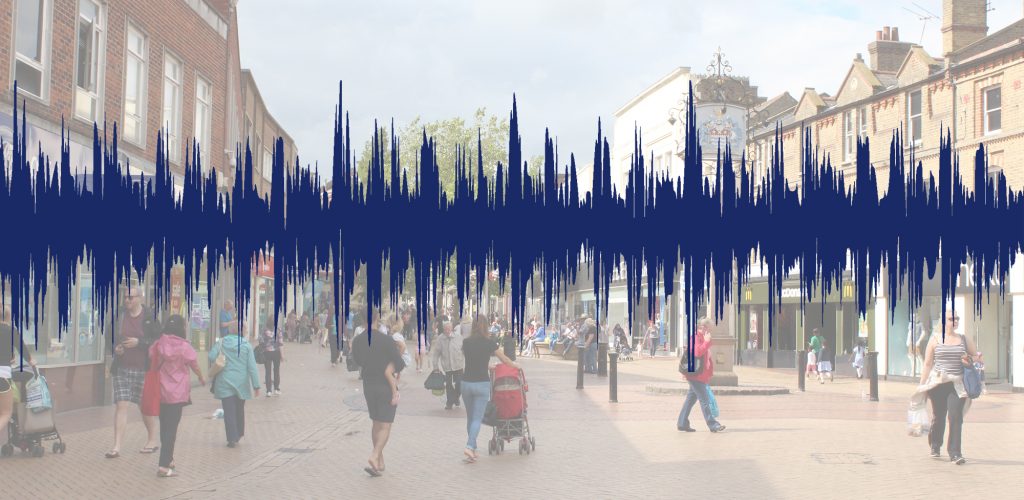

Sometimes, these overlaps can serve to emphasise differences. The first bench I visited was in Chelmsford on a cold morning in February. In a BBC Essex clip from 1992, an optimistic speaker describes the opening of the shopping centre. Sounds of buoyant crowds exploring new shops pin an alternative image over my contemporary view from the bench, the closed shutters of high street restaurants, and wind howling down the shopping streets.

BBC Essex report on the opening of The Meadows shopping centre in Chelmsford, used for the listening bench in Chelmsford (SA 1/1030/1).

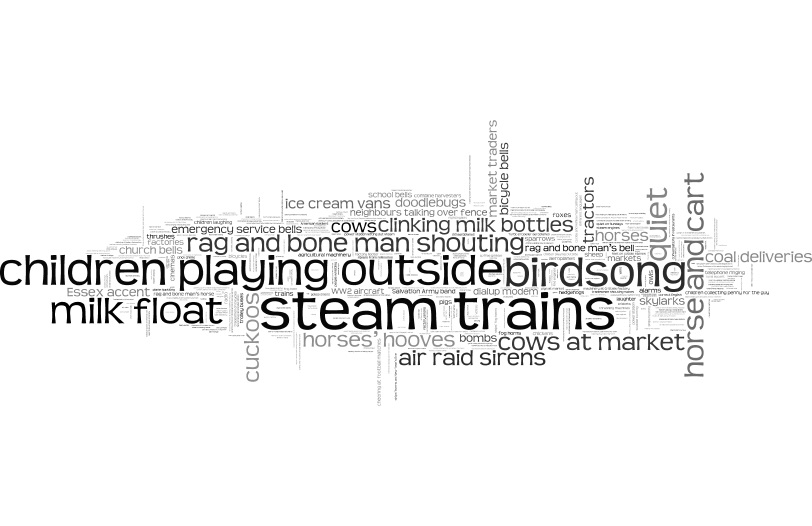

Environmental factors pose risks to the benches which they may not face in museums. Some benches suffered a lack of solar-power, and weather can affect engagement in other ways. I visited the benches in the week preceding the arrival of the snow from Siberia, the ‘Beast from the East’ and so Southend Pier was closed, meaning its bench was inaccessible. There is also an enhanced risk of vandalism. The Bowers Gifford bench is located in Westlake Park, behind quiet residential avenues. It sits in silence, solar panel smashed, demonstrating the risk of liberating installations from museums. However, visiting the benches made me reflect on the difference which hosting oral histories outside of the Record Office can have, contributing to an enhanced engagement and alternative interpretation of the sounds and testimonials. The bench in Raphael Park plays a song, ‘’Owd Rat-Tayled Tinker’ in Essex dialect of the 1920s.

The ”Owd Rat Tayled Tinker from ‘Owd Lunnon Town’, sung by J. London in 1906, and used on the touring listening bench while it was at Raphael Park (SA 24/221/1).

Broadcast into the park, it can overlay a range of accents spoken by current park visitors. When I visited, this was most notably a man nearby on his mobile, with an Estuary accent like my own. This accent is associated with Romford and other parts of Essex, and influenced by post-war migration from London, as people moved out into the county.

Touring listening bench in Raphael Park. Copyright Jade Hunter.

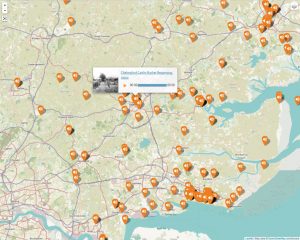

My experience of Essex has been shaped by growing up in Thurrock on a suburban council estate close to industrial riverside and the greenery of Rainham Marshes. There are spots where you can see the London skyline, and remain within walking distance of the shopping centre, Lakeside. It’s easy for perceptions of a place to be shaped by media representations, or limited to your own experience of a small section of it. Visiting the benches enabled me to understand more about the variety of landscapes and people that make up Essex, and the ways in which these have changed over time and continue to do so. They made me reflect on those spaces that serve as home to smaller communities, and those which are temporarily shared and experienced by people visiting from elsewhere, the market in Romford, the country park in Hadleigh, and the pier in Southend.

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.

Find out more about the benches and their current locations on our Essex Sounds website. Then share your #benchselfie with us and tell us which is your favourite clip!