Hannah Salisbury, Engagement and Events Manager

Archives are packed with thousands upon thousands of life stories. And individual life stories are not only interesting in themselves, but can tell us about the society that individual lived in, and even human nature itself.

You will not, however, find someone’s life story all in one place. Records of our lives are scattered piecemeal through innumerable different records; the fragments that can be gleaned from various records can pinpoint people in time – when and where they were born, married and died, where they lived, what job they did. Sometimes, we are lucky enough to find records which give us more detail of what somebody looked like, or of their particular life experiences, which help us to imagine the world from their point-of-view.

When we run training courses on archival research, one of the things we say is that you will likely have to use several different sources to piece together the jigsaw. This work is, of course, immeasurably aided by the availability of key source material online, much of it accompanied by searchable indexes. A piece of research which would have once taken months or years or even been impossible can now sometimes be accomplished in a matter of hours.

The detective work which goes in to piecing together someone’s life story from archival records can be addictive. So it has been the case with William Swainston, a Victorian orphan who was admitted to the Essex Industrial School in 1876, aged 11, having been found sleeping rough in an outhouse at Parson’s Heath near Colchester. We have written previously about the Essex Industrial School, and its records have proved too tempting to resist further investigation.

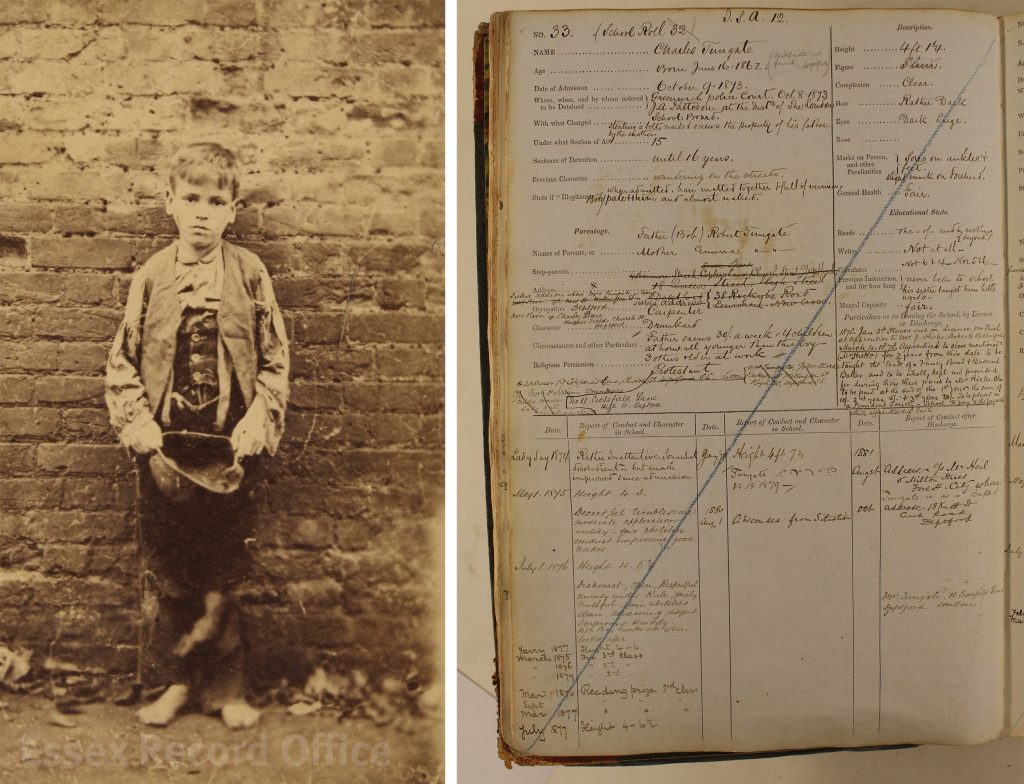

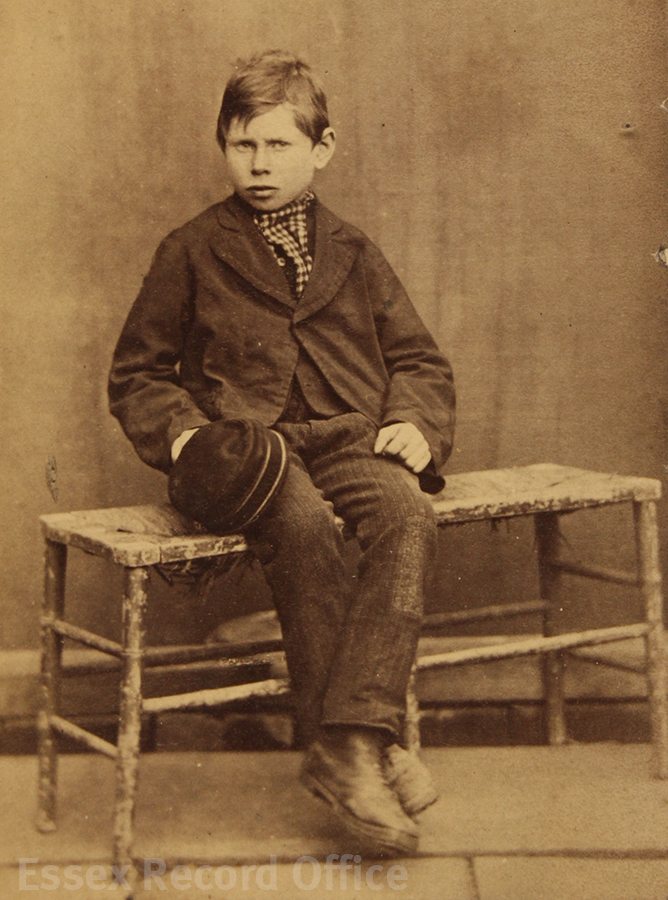

William Swainston, who joined the school in 1876, aged 11, having run been orphaned and run away from his half-brother. Photo by Edouard Nickels (D/Q 40/153)

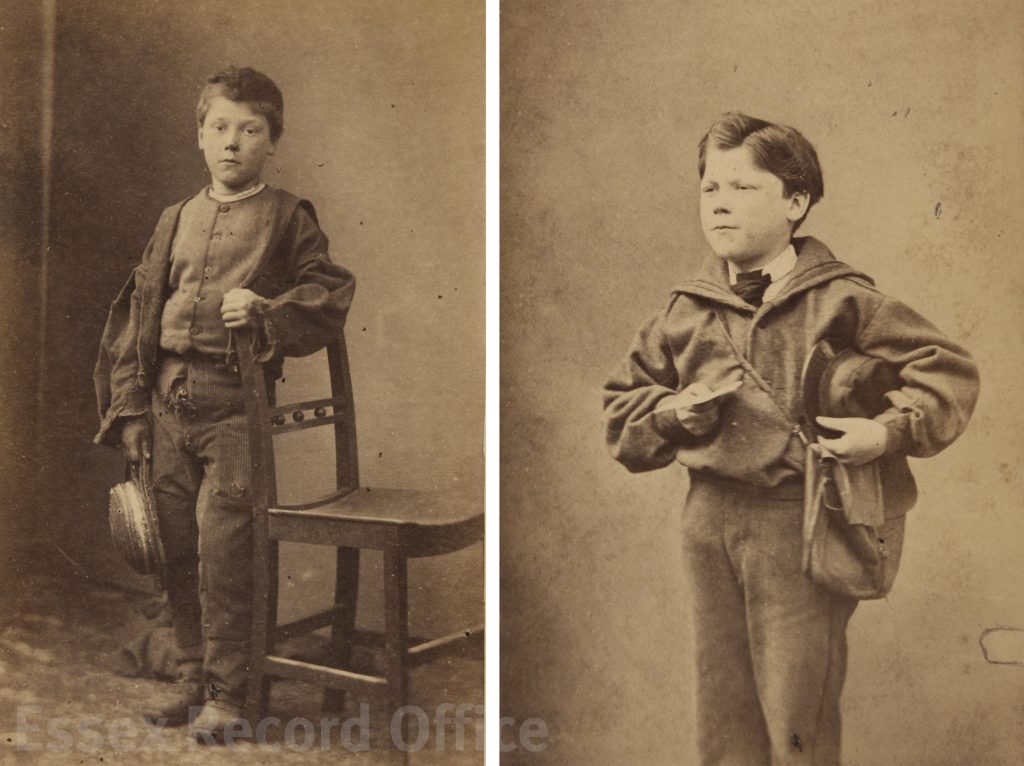

William is one of the school’s pupils of whom we have a named picture. This picture can then be tied up with his school records, so we can put a face to the boy described in the written records, and discover the story of the small boy looking out at us from this 140-year-old photograph. It has then been possible to pick up his story in other records, including newspapers, which have provided incredible detail of William’s turbulent life story.

William had had a difficult start in life. He was born in 1865 in Leicestershire, to parents Henry Thrussell Swainston and his wife Mary (his birth was tricky to track down, having been registered as William Thrussell). Henry’s occupation was described variously as a ‘chemist’, a ‘druggist’, and a ‘medical practitioner’. Henry was over 35 years older than Mary, and had had children from two previous relationships. Before William was born, the couple had had two other sons who both died in infancy. In 1871, when William was 6, his mother died. His father committed suicide 12 months later.

When William was orphaned, he went to live with his much older half-brother Charles Swainston in Colchester. Charles had himself had a difficult start in life; his mother had died young and his father seems to have disappeared.He was a former military man (indeed, it was the army which brought him to Colchester), and then became a Police Constable. Judging by newspaper articles, Charles seems to have been a respected figure in Colchester. When he died in 1906, a short article in the Essex Newsman noted:

The funeral has taken place at Colchester of Mr. Swainston, for many years caretaker of Colchester Castle. The deceased served as a soldier both in the Crimea and Indian Mutiny, and was greatly esteemed by all who knew him.

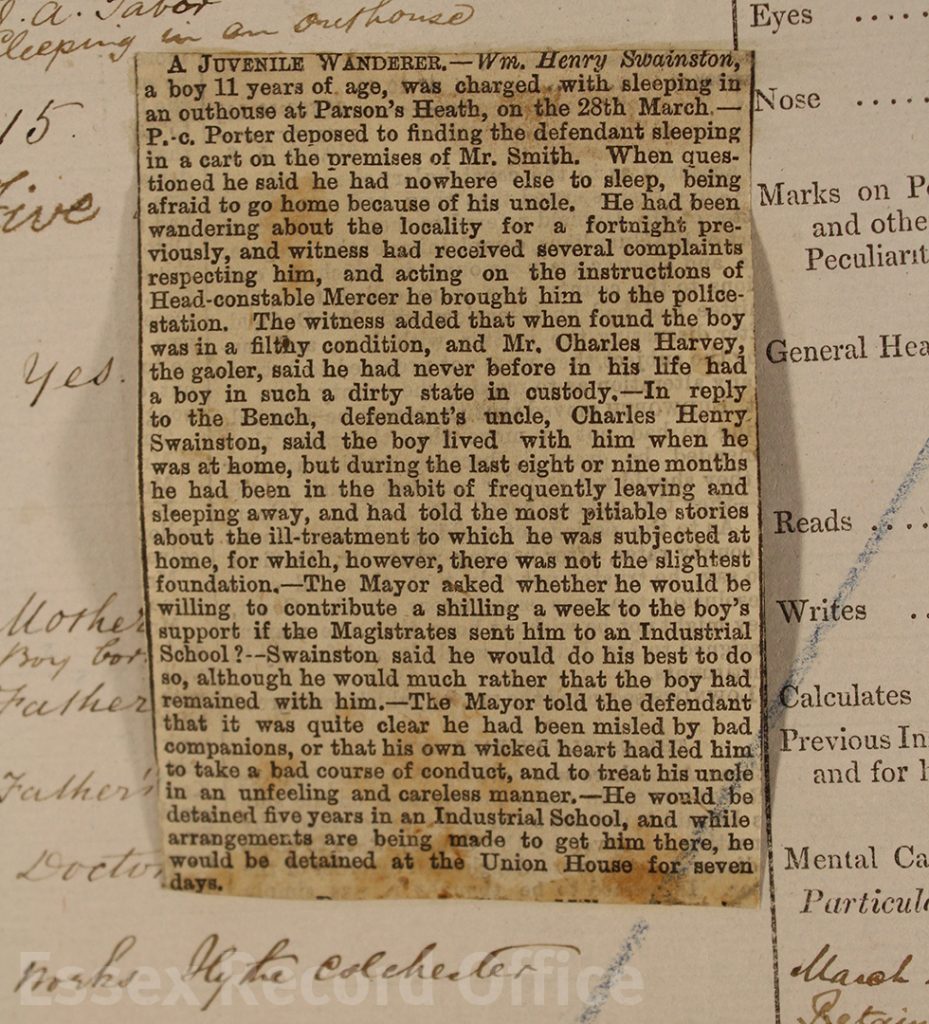

Yet William’s life with Charles’s family was not a happy one. In March 1876, William was arrested under the Vagrancy Act for sleeping rough in a cart on Parson’s Green near Colchester. The officer who arrested him said that William was ‘in a filthy condition’. According to a newspaper article affixed to his school records, William said that ‘he had nowhere else to sleep, being afraid to go home’ because of his half-brother.

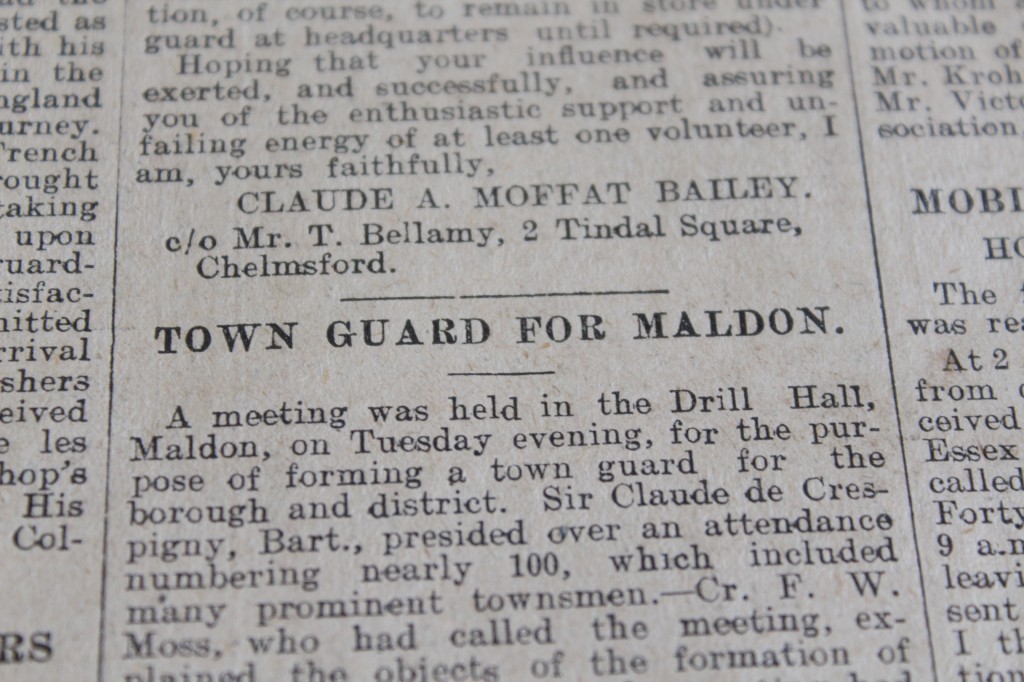

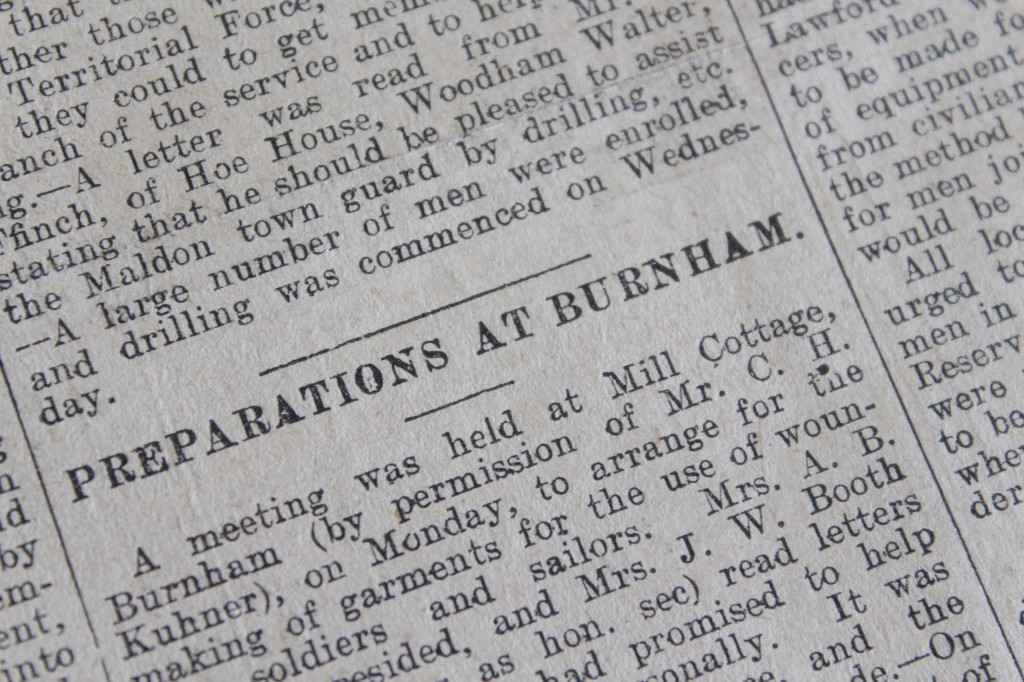

The newspaper article affixed to William’s school records. The uncle mentioned was really William’s half-brother. (D/Q 40/1)

A hearing was held in Colchester Town Hall in front of the Mayor, at which William’s half-brother Charles also appeared. The Essex Standard of 31 Marcy 1876 reported that Charles denied William’s claims of ill treatment, and said that the boy ‘had been a source of great trouble and anxiety to his foster parents’. The Mayor admonished William for his unfeeling treatment of his benefactors, and suggested he be detained in an Industrial School as he was ‘evidently just entering on the path of crime’.

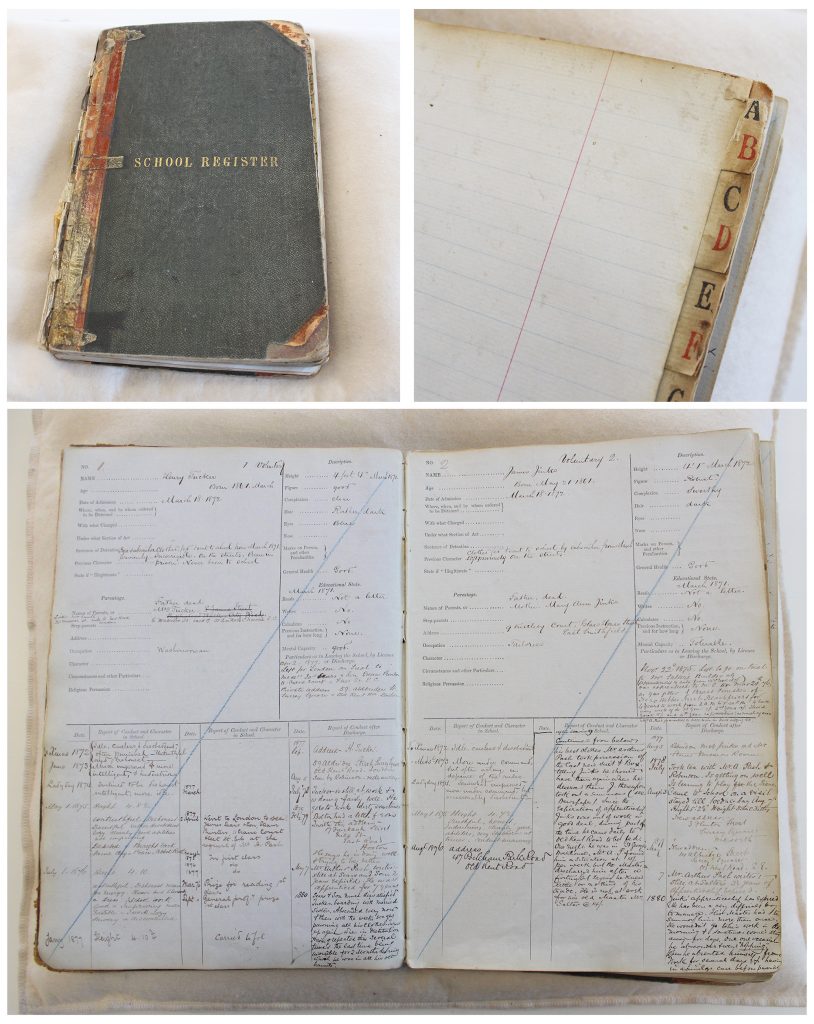

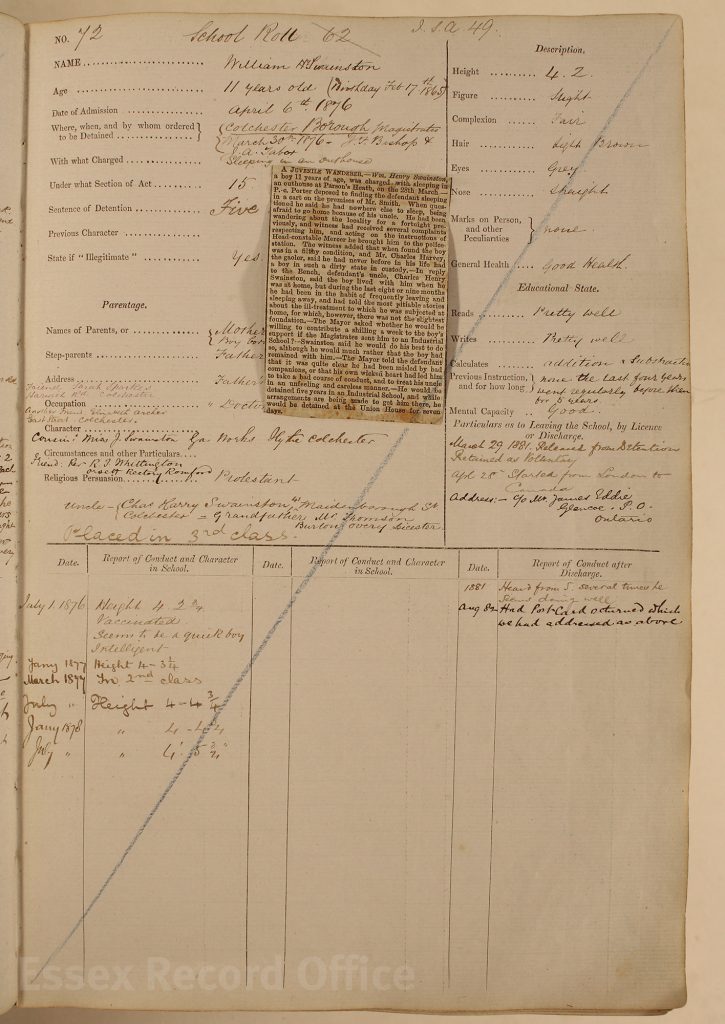

The next place where we pick up William’s story is in his school records. He arrived at the Essex Industrial School in Chelmsford on 6 April 1876. He was 4’2” tall, his figure ‘slight’, complexion ‘fair’, his hair ‘light brown’, his eyes ‘grey’ and his nose ‘straight’. Unusually among the boys, he could read and write ‘pretty well’. He had attended school regularly for five years, but received no schooling for the previous four. His report on 1 July said that he ‘seems to be a quick boy’ and described him as intelligent.

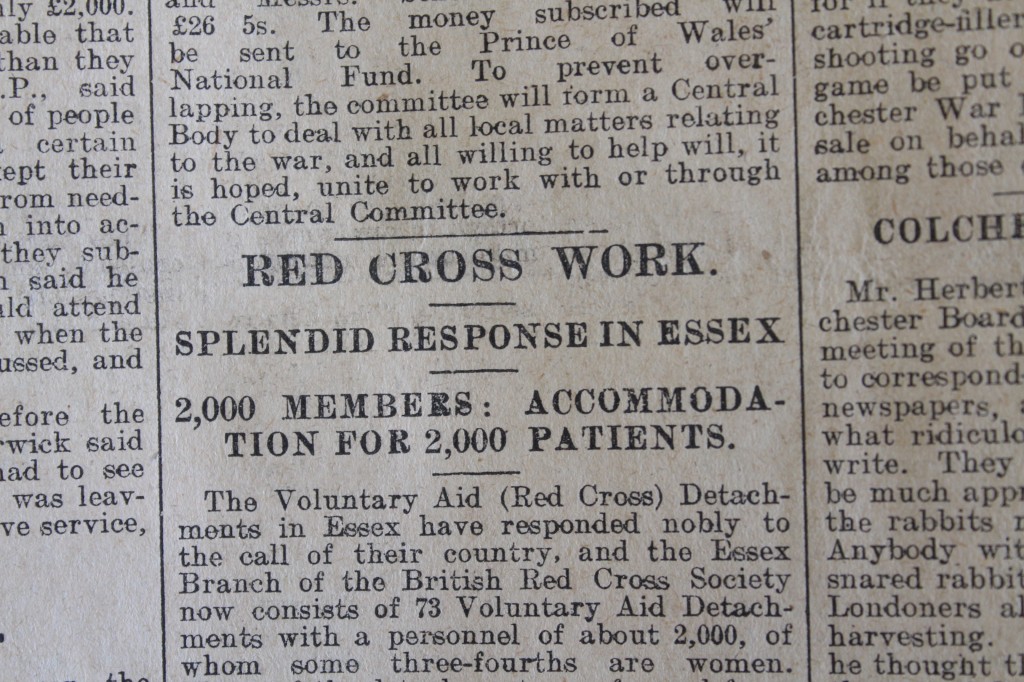

William Swainston’s record page in the Essex Industrial School admission register (D/Q 40/1)

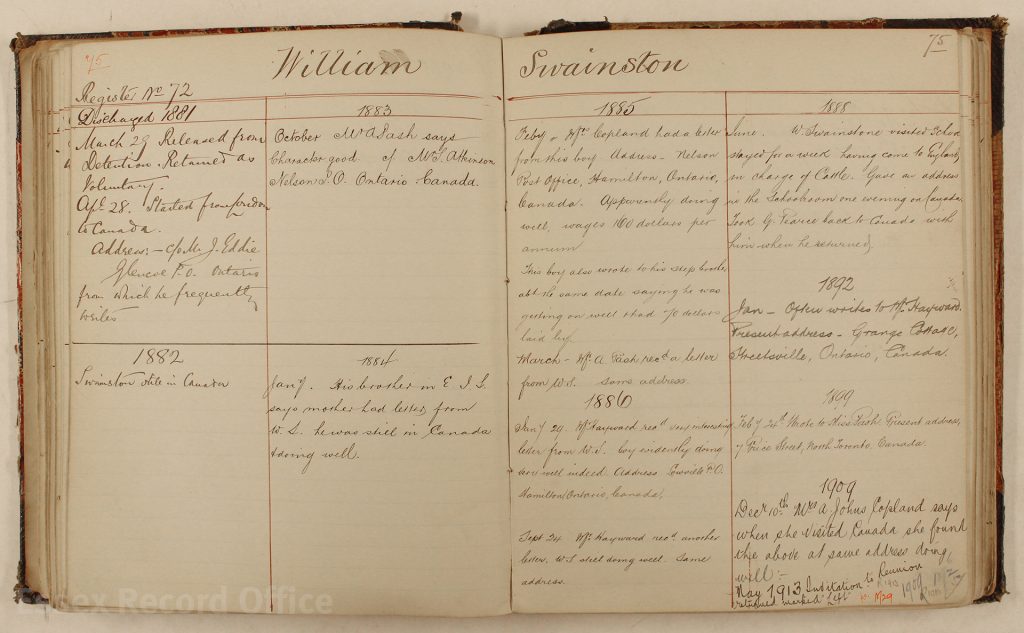

William’s school records are not as detailed as some of the others, but they do tell us that in April 1881 he set out for Canada, aged 16. In 1881 it was noted that they had heard from him ‘several times he seems doing well’.

William also appears in the school’s discharge registers (D/Q 40/12), which gives more detail of the contact the school had with him after he left. The notes include in 1884 that ‘his brother’ in the school said that his mother had received a letter from William – this must be Francis Bulwer Swainston, who was actually William’s nephew, of whom more below.

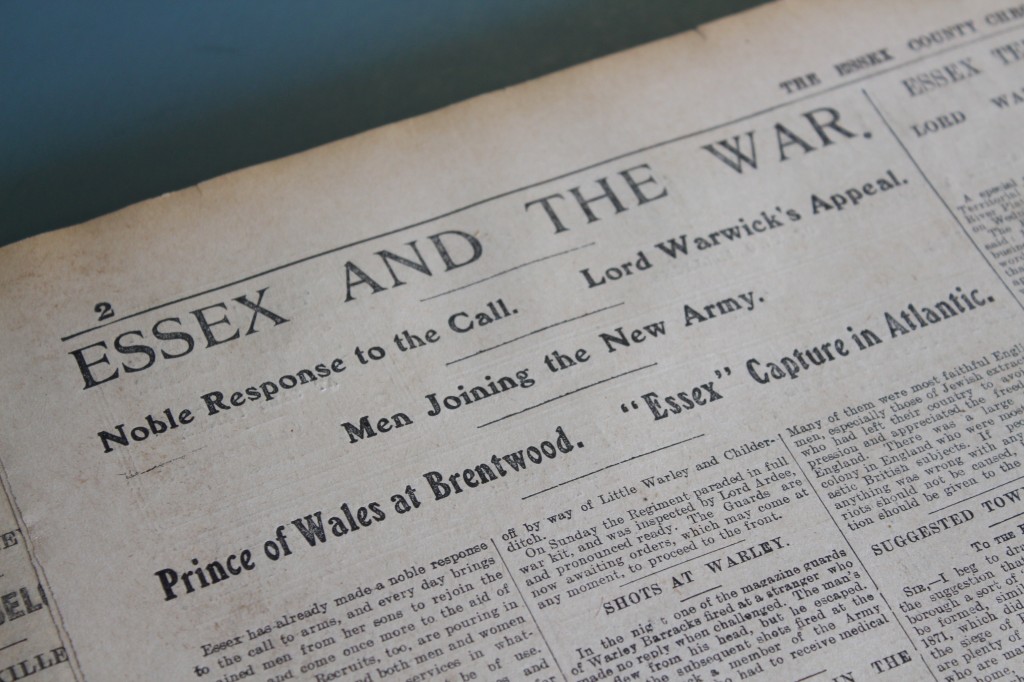

Seven years later, in 1888, William was back in England with a consignment of cattle, and during this trip visited his old school to give a talk about his life farming in Canada. A short report on the talk appeared in the Essex Standard of 16 June:

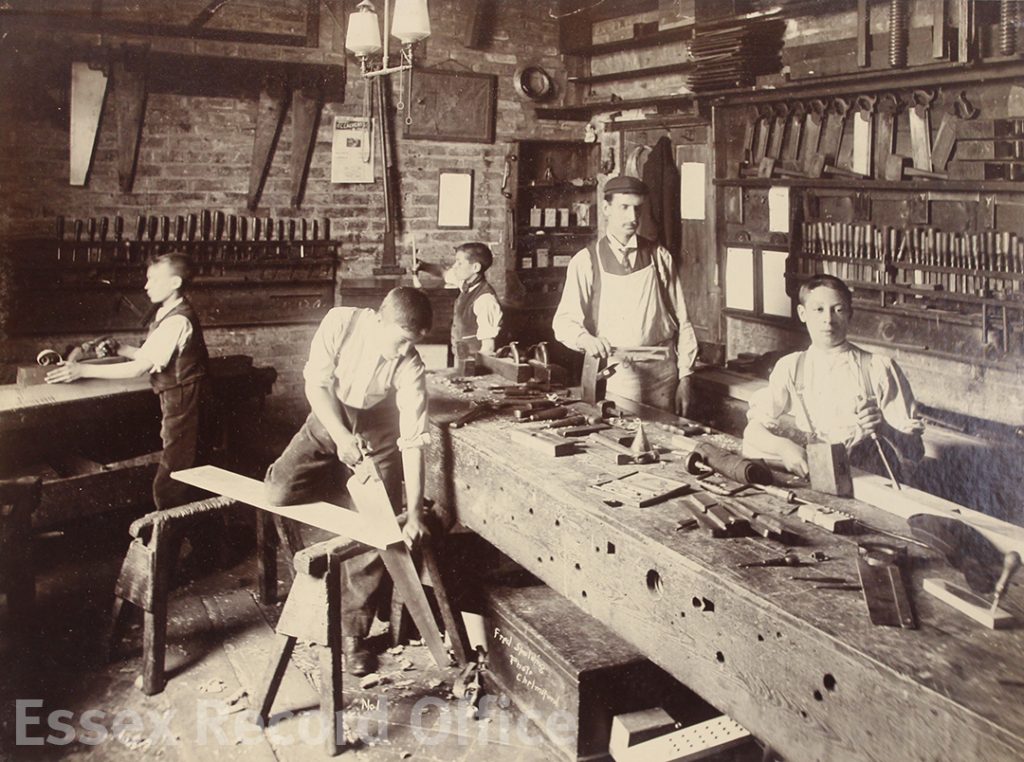

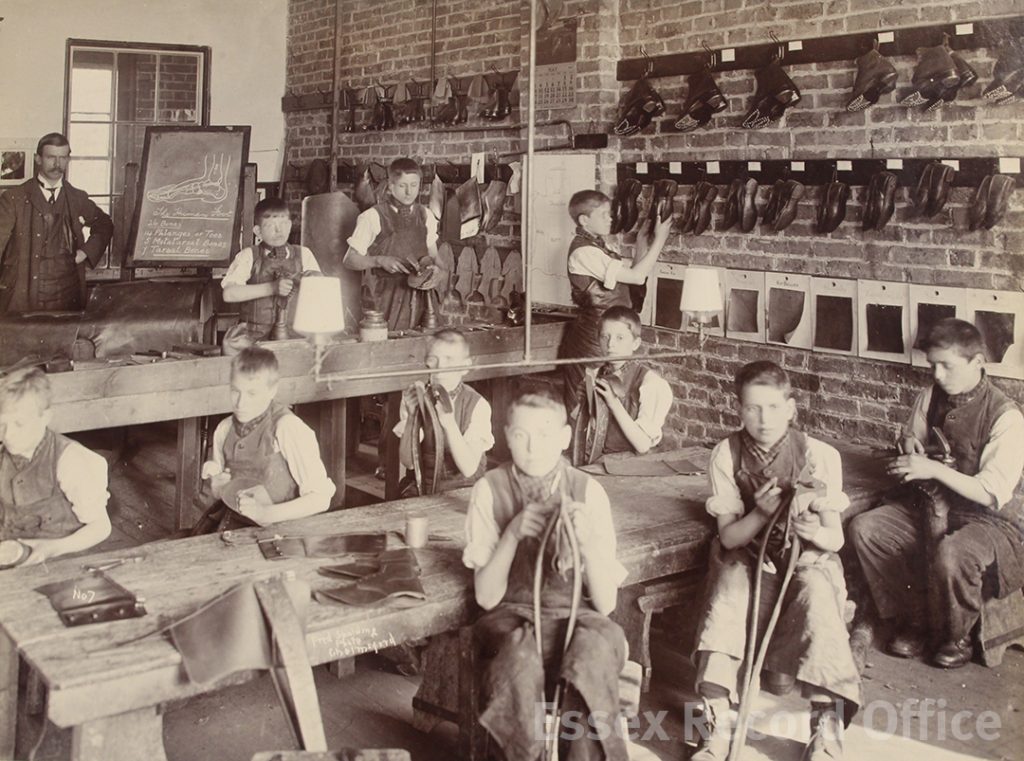

Essex Industrial School – On the evening of the 7th inst. an interesting address was delivered at this Institution by Mr. Wm. Swainston, of Lowville, Canada, who was at one time an inmate of the School, and has been for seven years in Canada. – Mr. Frederick Wells presided, and was supported by Mr. J. Brittain Pash [the founder of the school], the Rev. R.E. Bartlett, and the Rev. D. Green. There was a crowded attendance of friends of the school, many of whom previously made an inspection of the buildings. – Mr. Swainston, who was most cordially received, began by describing his life on a Canadian farm, after which he spoke generally of the way in which agriculture was carried on there. In answer to questions, which were invited, Mr. Swainston stated that an industrious young man could save a hundred dollars a-year; he himself had saved that amount in a single summer. He mentioned that the knowledge he had acquired of various trades at the School had been most useful to him. He had come over to England with a consignment of cattle… A charge of 3d. was made for admission to the lecture, and the sum obtained will go towards sending a boy to Canada.

William seems to have made a good go of life in Canada. In March 1892 in Peel, Ontario, he married Helen or Ellen Quinn, who originated from Ireland. Both were aged 24, and William was described as a farmer. The last record it has been possible to trace so far for William is the 1901 Canadian census, in which he is recorded in Toronto along with Ellen, and three children – E. Mary, Annie, and William.

As a footnote, William was not the only member of his family to end up in the Essex Industrial School. Somewhat embarassingly for William’s half-brother Charles Swainston, one of his own sons, Francis, was in trouble throughout his childhood for a series of petty crimes, and in 1884, being deemed ‘uncontrollable’, was sentenced to be detained at the Essex Industrial School until he was 16. In the week before he was sent there he was kept at the Colchester workhouse, and three times escaped, once with no clothes on. His time at the school doesn’t seem to have deterred Francis from a life of crime, and as a young man there are further reports of him getting in trouble with the law for running confidence tricks. His crimes seem to have petered out, however, and he went on to work as a painter/decorator and as a tailor, and married and had 10 children.

If there are any living descendants of William’s out there, then I hope this post finds them.

If you would like to research further life stories of the boys in the Essex Industrial School admission books, you can find and order the books through our online catalogue (search for ‘Essex Industrial School admission register’, and use sources such as the census (available online for free in our Searchroom) and newspapers (again, available in our Searchroom) to find out more.