Andy Begent has created a website recording biographical details of 460 men connected with Chelmsford who lost their lives as a result of the First World War, including photographs of them where possible. In this blog he writes of one of the unexpected tasks that he has dealt with in that ongoing project.

Recently someone asked me what had been the biggest challenges which I had faced during the creation of the Chelmsford War Memorial website.

I think they expected me to respond by talking of the difficulty in researching the lives of the fallen so long after they died. Though that research can be time consuming, laborious, occasionally frustrating, yet often rewarding, I have found the biggest challenge has been the apparently simple task of determining whether a person should or should not be included on the website.

I think they expected me to respond by talking of the difficulty in researching the lives of the fallen so long after they died. Though that research can be time consuming, laborious, occasionally frustrating, yet often rewarding, I have found the biggest challenge has been the apparently simple task of determining whether a person should or should not be included on the website.

Early on in my research I was faced with a choice: should the website only commemorate those named on the Chelmsford Civic Centre war memorial, or should it include others that I had identified as having strong Chelmsford connections but who been omitted from that memorial?

I soon discovered that the process to select the names for the memorial had been imperfect. The draft list of names was issued as late as July 1923 to the public for comment upon, with the finalised list later determined by the Mayor and Town Clerk. That delay of almost five years after the end of the war meant that there was every chance that relatives or friends of some of those who could have been included on the memorial were no longer in a position to suggest their names.

Leading Seaman Samuel Allen Barnard, killed aged 26 when H.M.S. Vanguard blew up in 1917. Read his story here

My initial analysis also revealed that some of those named on the memorial had left Chelmsford several years before the war – some to settle in other parts of the country, and others who emigrated abroad, to Canada and Australia. They appeared not to have set foot in the town for some time, if at all, since their departure, yet their names were included on the memorial.

Having identified those potential shortcomings I decided I would include on the website all those mentioned on the war memorial plus those with a strong Chelmsford connection who had been omitted from the war memorial. I then just needed to determine what ’strong Chelmsford connection’ meant.

I looked to the past for clues.

Almost a century ago those erecting war memorials after the First World War had to determine their own inclusion/exclusion criteria, with the criteria varying from memorial to memorial. The Chelmsford approach seemed to be inconsistent, but maybe if I looked at other memorials I could identify best practice.

I soon established that war memorials that commemorated the war dead who attended a particular school, or church, or club, or place of work would have been fairly straightforward to compile names for – either the individual had attended or they had not.

Leading Mechanic Arthur Evan Thomas, R.A.F. Read his story here.

Other types of memorial would have been more challenging. Those that commemorated war dead of towns (and villages, parishes etc.) often used residency as the primary criteria for inclusion. Usually a person was included on such a memorial if they had been resident in the town at the time they began military service. They may also have been included if they died in the town as a consequence of their military service. Some war memorials broadened the residency scope wider than the individual; they may have included an individual on a town’s war memorial even if the individual did not reside in the town when they joined up or died, but their parents, spouse or next-of-kin siblings did, either at the time of them joining up or of their death. This broadening of scope means that some individuals’ names appeared on more than one war memorial – some of Chelmsford’s also appear on town and village war memorials in other parts the UK and further afield.

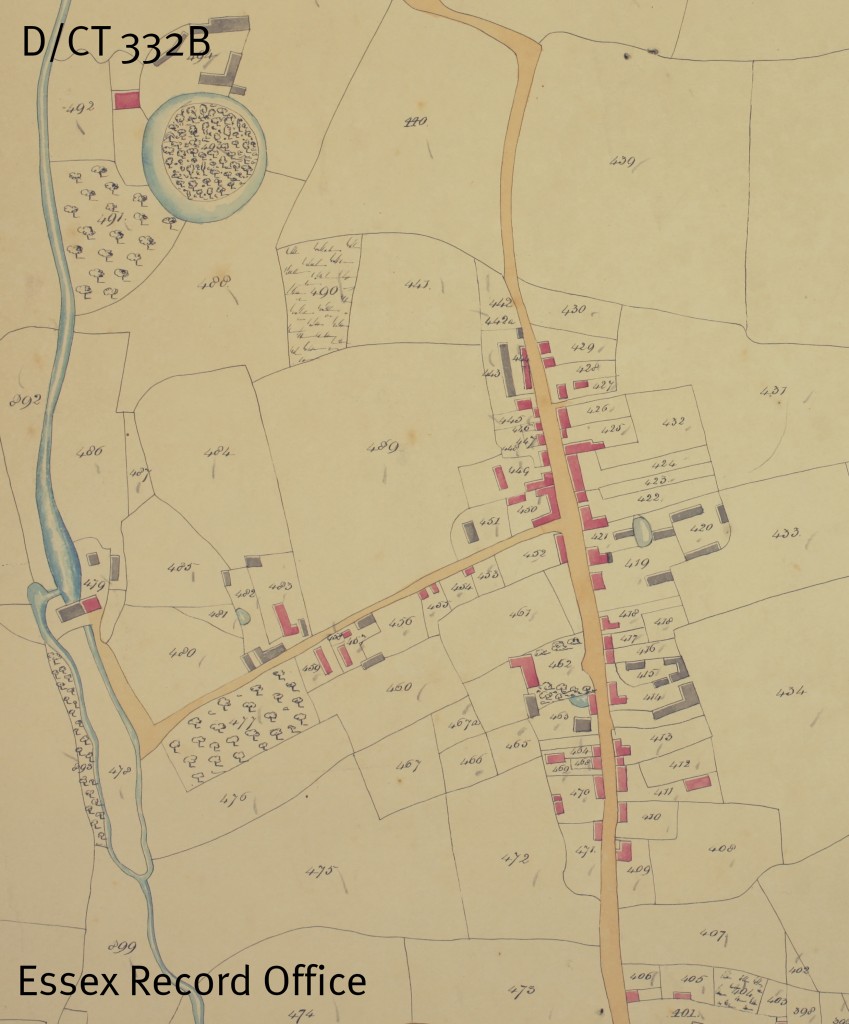

Even the boundary of a town can be difficult to determine. Chelmsford’s Civic Centre war memorial generally uses the Borough Boundary of 1923 but also includes residents from beyond. The 1923 Borough did not include parts of Widford which were added to the Borough in the 1930s. Great Baddow, Broomfield and Writtle were not absorbed in to the Borough until 1974.

Other criteria, beyond residency, may be considered when selecting names for a war memorial, including date of death, cause of death, and whether the individual was serving or had served in the military.

Corporal John William Hooker, 7th (Service) Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, killed in action in 1918. His brother, George Alexander Hooker, was also killed in the war. Read his story here.

Some war memorials restrict their commemorations to those that died or were killed between the war’s outbreak on 4th August 1914 and the Armistice of 11th November 1918. Others stretch that to the Treaty of Versailles of 28th June 1919 when peace with Germany officially started. For the First World War the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) commemorates deaths from 4th August 1914 up to 31st August 1921. Others go beyond, recognising that the war led to wounds and illness that led to the deaths of servicemen for decades after the war. The last of those to die who is commemorated by Chelmsford’s Civic Centre war memorial is Douglas Havelock Newman, a former prisoner of war, who died on 7th May 1922, well past the CWGC cut-off date.

Some war memorials include only those who were killed in action or died of wounds. Others expand on that to include those that died of illness, accident or even suicide. The CWGC makes no distinction around causes of death when determining if a person should be commemorated. Chelmsford’s Civic Centre war memorial includes all of those except suicide, although two soldiers who committed suicide are buried in the town.

Some war memorials include only those who died whilst serving in the military. Others go beyond that to include ex-servicemen and civilians. The CWGC commemorates anyone who was still in military service or members of certain civilian organisation (such as the Red Cross) at the time of death, but also includes those who had left the military and died up to 31st August 1921 as a result of an injury or illness caused by or exacerbated by their service up to that date. The Chelmsford Civic Centre war memorial includes a member of the Red Cross, but it does not, and neither does the CWGC, include a civilian from Chelmsford, John Thomas Bannister, killed in a German air raid on London during the First World War.

Having pondered those factors I have ultimately come up with the following criteria which I employ to determine whether someone should be included on the website. You will see is not simple and certainly not as simple as I would have liked.

An individual will be recorded on the website where:

- They are mentioned on Chelmsford’s Civic Centre war memorial or the Moulsham, Springfield or Widford war memorials, or

- They or their assumed next of kin were resident in the Borough of Chelmsford of 1923 or parishes of Widford and Springfield at the time they began military service or at the time they were killed or died, or

- They died or were buried within those same areas, and;

- Their death is commemorated by the CWGC or their death is proven to have been as a result of an injury or illness caused by or exacerbated by their military service or enemy action.

Determining to what extent these criteria apply so long after an individual’s death is not always easy. We do not have comprehensive records of all those who served in the military nor of those who lived in Chelmsford. The 1914-15 and 1918 registers of electors provide some evidence which can be used, as do contemporary newspaper reports, cemetery and church records. Perhaps the greatest untapped source of information is the stories passed down through families and I hope that the war’s centenary will bring many of the latter to the fore.

If you would like to view the Chelmsford War Memorial website follow this link: http://www.chelmsfordwarmemorial.co.uk/Chelmsford_War_Memorial/Home.html

Andy will be giving a talk on some of the stories he has come across during his research at Essex at War: 1914-18 at Hylands House on Sunday 14 September. Click here for details.