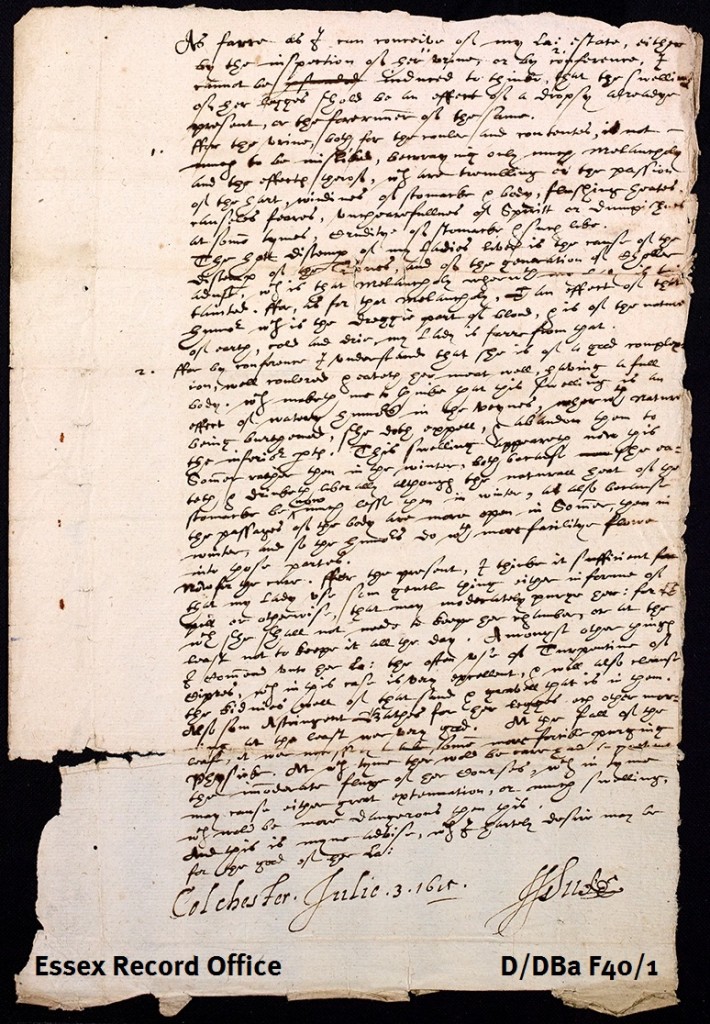

As we experience some of the warmest temperatures on record for the UK, Archivist Katharine Schofield finds out how hot weather affected some of our ancestors, using the voluntary rate book for Belchamp Walter, 1883-1920 (D/P 215/4/2)

So far 2018 has seen the warmest May on record and the driest June, followed by near-record high temperatures in July, and it appears to be destined to become a long-remembered summer, like that of 1976. While we can enjoy the air-conditioned temperatures of the ERO Searchroom, and currently there are no plans for any restrictions on water use in the county, we should spare a thought for residents of Essex in years past who had no respite from hot temperatures and the longer-term consequences.

The years between 1890 and 1910 witnessed what has been called the ‘Long Drought’. A series of dry winters were exacerbated by several hot summers causing major problems with the water supply. In Belchamp Walter the wells dried up in the autumn of 1905.

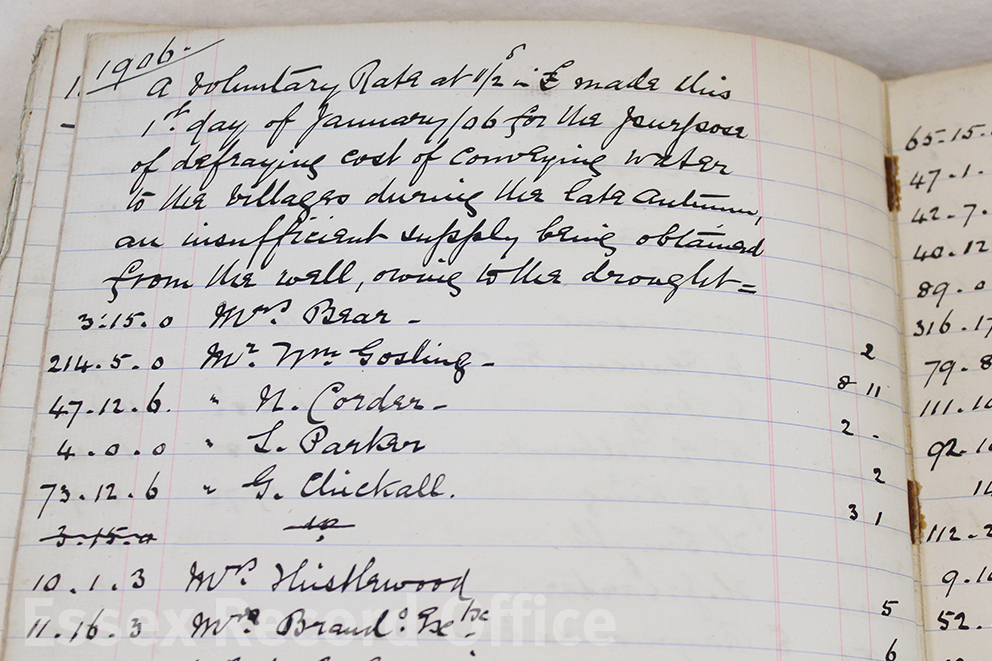

In 1906, the ratepayers of Belchamp Walter were asked to contribute to the cost of bringing water to the village after their well ran dry

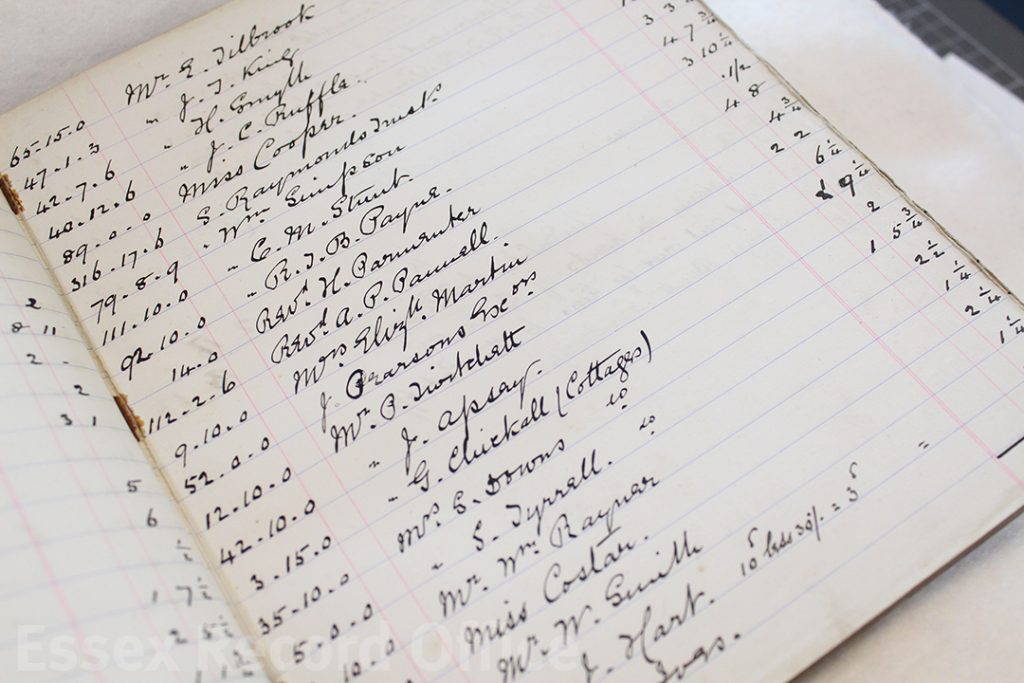

The amounts paid by individuals are recorded in the rate book, and add up to a total of £3 10s 1 1/4d

On 1 January 1906 the ratepayers of Belchamp Walter were asked to contribute towards a voluntary rate ‘for the purpose of defraying cost of conveying water to the villagers during the autumn, an insufficient supply being obtained from the well, owing to the drought’. A total of £4 0s. 9¾d. (around £317 today) was assessed to be due, although 10s. 8½d. was not collected, leaving a total of £3 10s. 1¼d. raised, the equivalent of around £275.

Of this sum, £2 17s. was spent on what was described as expenses, with a note that the balance of 13s. 1¼d. had been in the hands of the Revd. A.P. Pannell and that he then paid this into the Post Office Savings Bank on 3 October 1906. It is not recorded how the water was taken to Belchamp Walter, but presumably it must have been taken there in barrels by horse and cart.

The rate book will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout August 2018.