Archive Assistant Neil Wiffen looks at a military operation crucial to ending the Second World War, which took place over 17-19 September 1944.

Essex played a vital role throughout the Second World War, being crucially placed to help in the defence of London, home to many important industries, as well as being a base for many British and American aircraft taking the fight to the Germans in occupied Europe. By the late summer of 1944, following on from the success of the Normandy invasion and liberation of much of occupied western Europe, there was a real hope that, after five years, the war could be finished before the start of 1945.

Flushed with the success of the advance across France and into Belgium the British commander, Field Marshall Montgomery, planned a new offensive for mid-September to drive a spearhead of troops that would outflank German defences by crossing the rivers Meuse, Waal and Lower Rhine. This would allow the deployment of armoured and mechanised forces to drive on Berlin and finish the war. In order to enable the ground forces to cross the many rivers in their way, para-troops and glider-borne infantry would be deployed to capture the bridges crossing them, creating a ‘carpet’ of friendly troops to make the advance of the ground forces as easy, and, crucially, as swift as possible.

Three airborne divisions were used: the American 82nd and 101st Airborne and the British 1st Airborne, the latter to be dropped furthest away from the relieving ground forces – their objective being the bridge at Arnhem. The airborne phase of the plan was codenamed MARKET while the ground-based operation was given the name of GARDEN. The lightly armed and equipped airborne troops had to be relieved as quickly as possible by the ground units – speed was of the essence. Perhaps the joint operation is most well-known to us from the 1977 film – A Bridge Too Far.

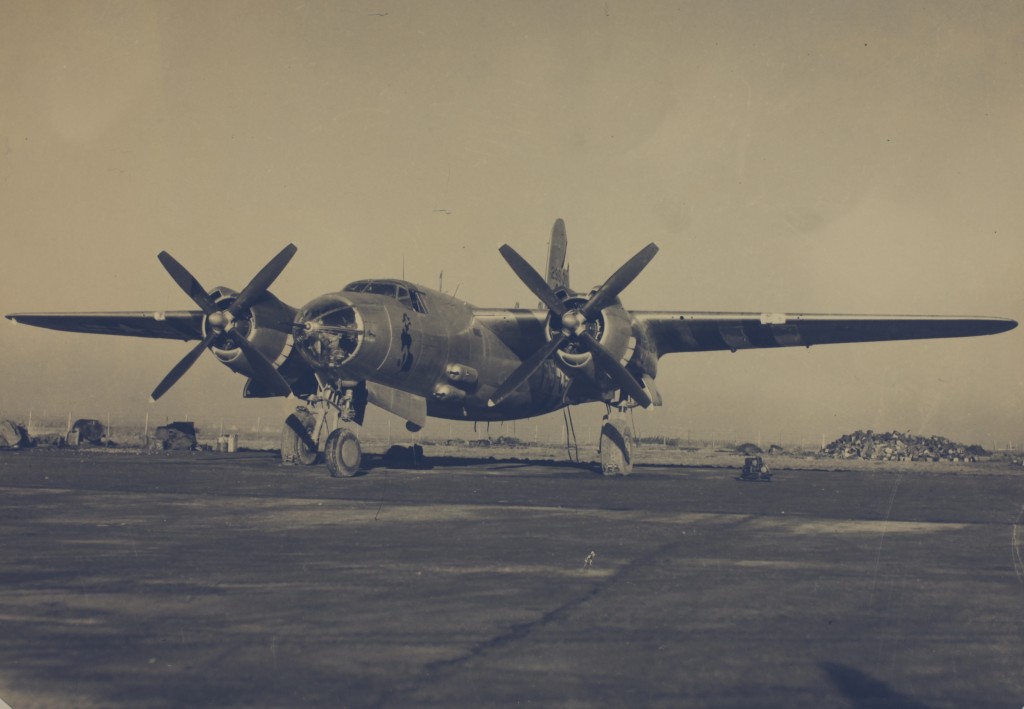

The operation commenced on Sunday 17 September. The first many people in Essex knew of it was when the vast aerial armadas of gliders (over 2,000 of these were on hand) and their tug aircraft (almost 2,000, mainly the famous Douglas C-47 Dakota, were available) flew over the county (the author’s father, then a teenager, retained vivid memories of the aircraft flying low over Broomfield on their way to mainland Europe). It is this phase of the operation that concerns us here.

Due to the large force of paratroops and gliders that were required, along with the dropping of supplies, several days of flying had to be undertaken to bring in more troops and equipment. This just added to the complex nature of running an airborne operation, increasing the risks inherent in conducting a successful engagement. The weather played a crucial part: gliders really did need quite still and stable conditions.to be launched. Conditions were not always kind. Early morning fog and mist delayed the launching of further reinforcement flights. By 19 September conditions had deteriorated, but resupply and reinforcement flights had to continue despite the risks.

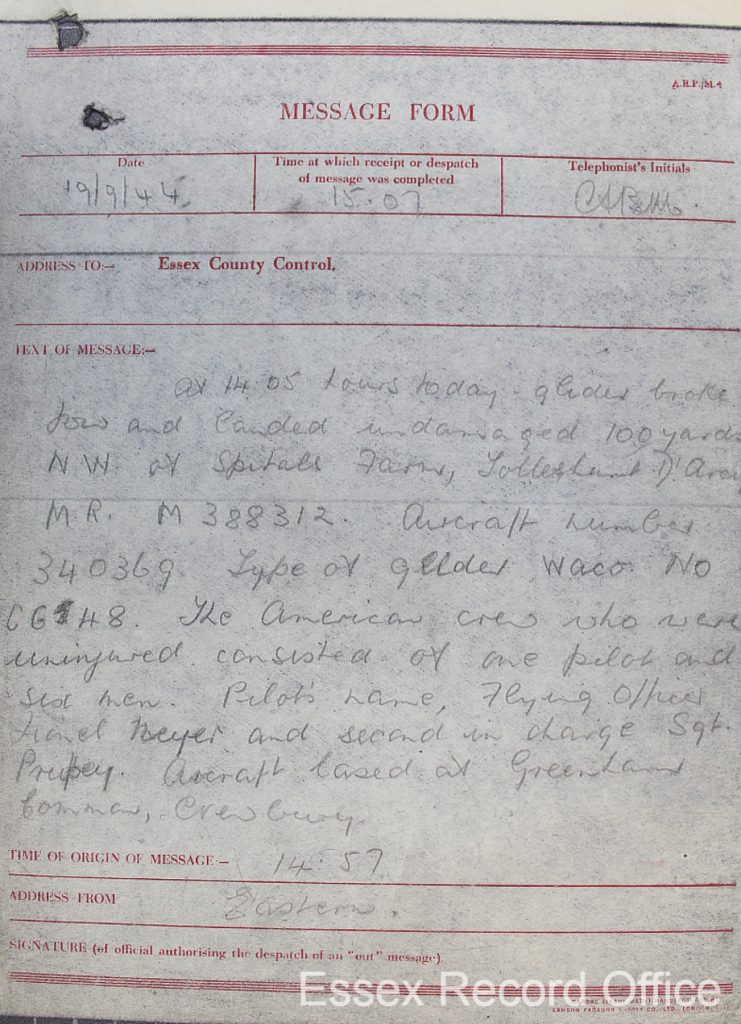

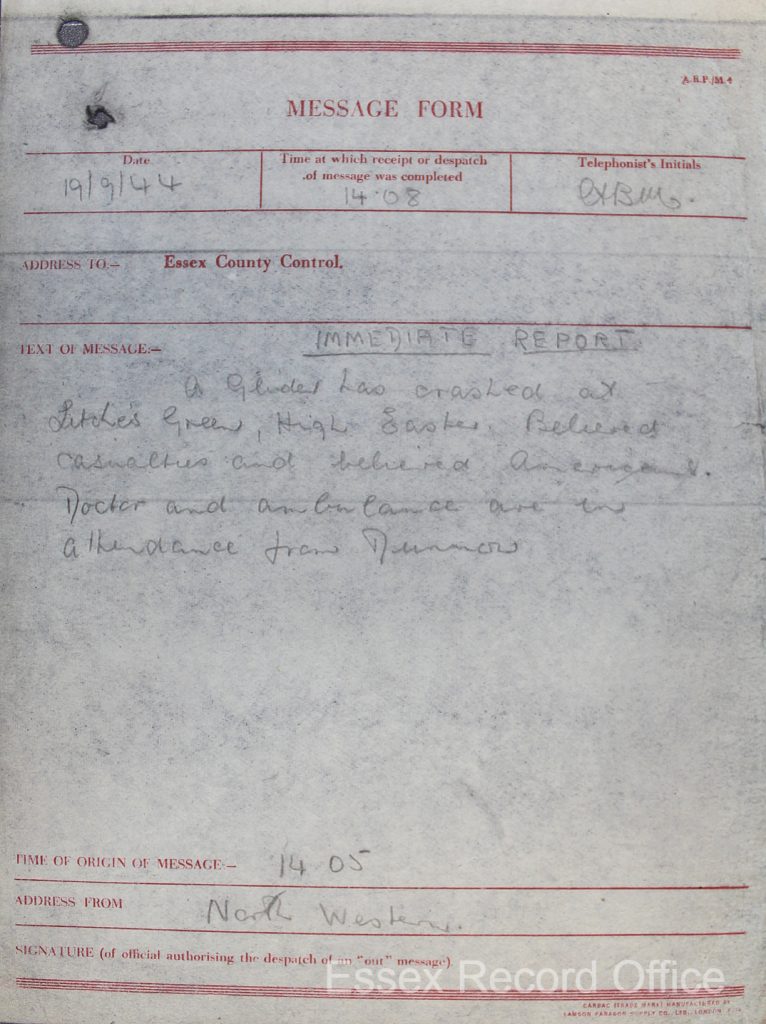

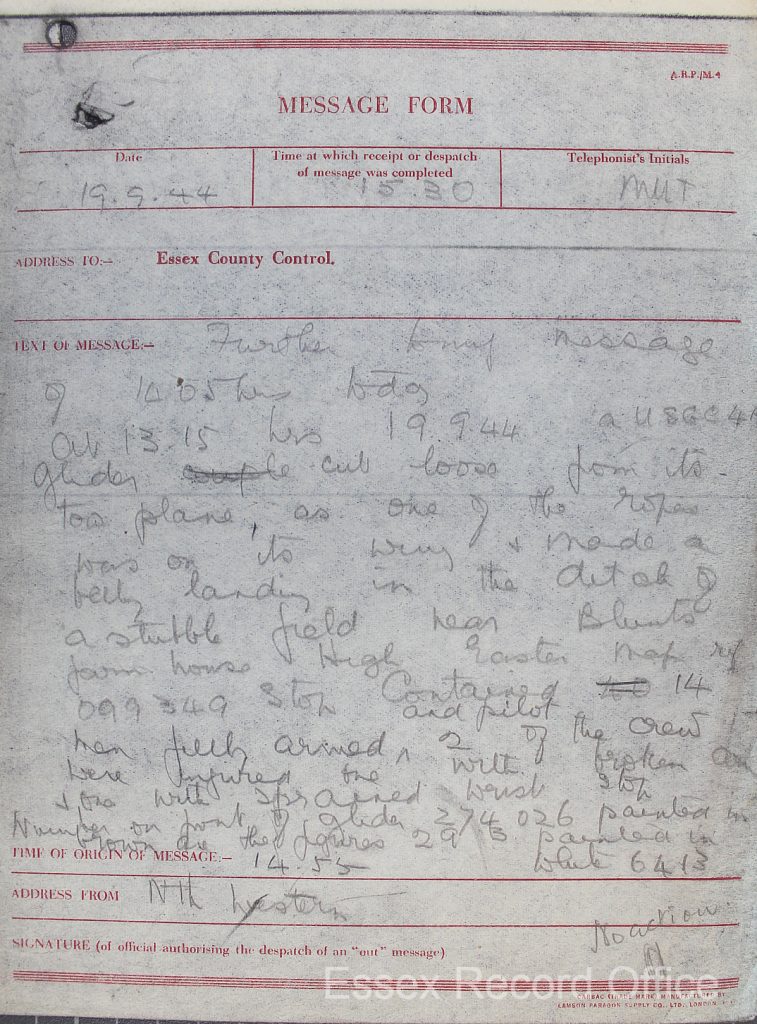

In the afternoon of 19 September, at 13:15, an American Waco CG-4 glider broke its tow rope and came down in a field, ending up in a ditch in High Easter. Fourteen soldiers and the two crew hadn’t made it to the continent. Shortly afterwards, at 14:05, another CG-4 came down for the same reason, along with its pilot and six soldiers, near to Spitals Farm, Tolleshunt D’Arcy.

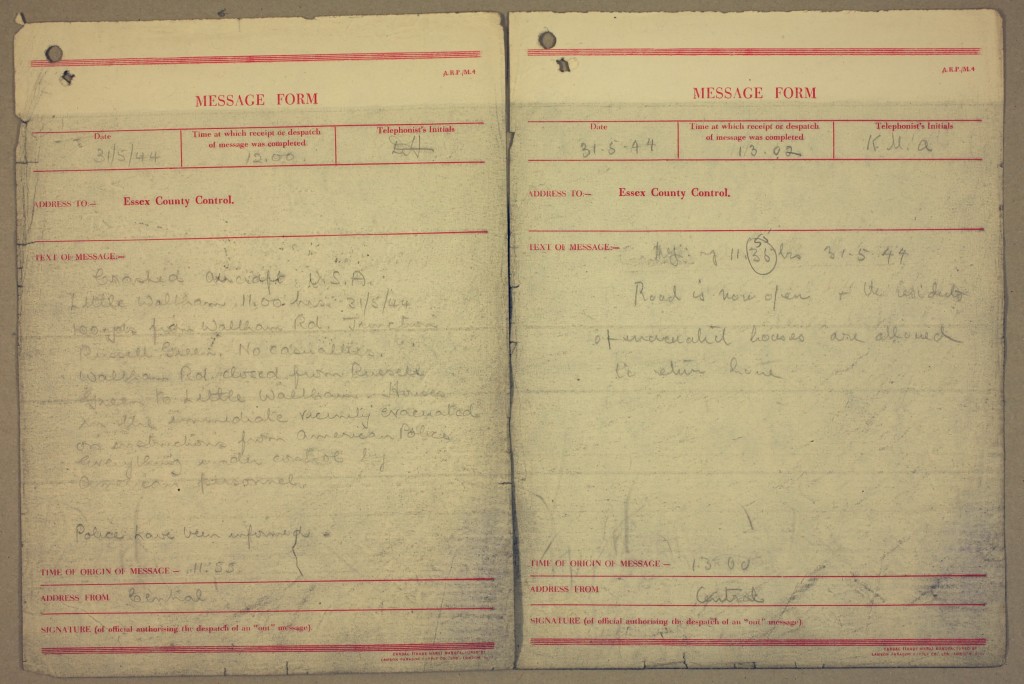

We know about these gliders because they were recorded in the Air Raid Precautions records which are still held at the Essex Record Office. These incidents are from the Crashed Aircraft series of records – three extracts below (C/W 1/11, click to enlarge images).

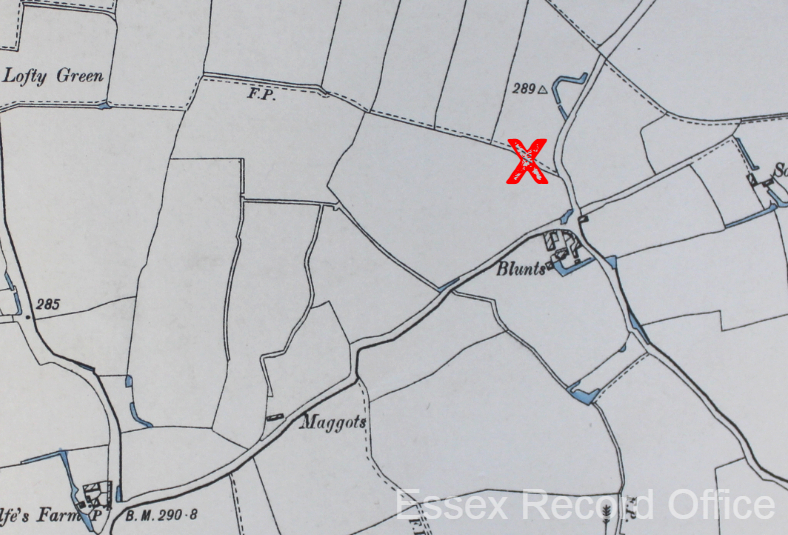

Of interest are the details contained in each report. A six-figure map grid reference is quoted for each report, which allows us to accurately plot where the event took place. These references correlate to the GSGS 3906 War Office series of maps (c.1940), which is different from our current National Grid Ordnance Survey (OS) map references. Luckily ERO has a set of these maps, and we include an extract to show where in High Easter the glider landed.

As the GSGS 3906 series of maps are at a 1:25,000 scale we have also included an extract of the same area from a 2nd Edition 6 Inch OS (1895) map which, while from the nineteenth century, does show the area in more detail. Also, being mapped on an individual county basis means that these earlier maps cover a different area. This allows us to also show Blunts farm, which is mentioned in the report but which is just off of the GSGS map extract – thus observing the First Law of Local History Research which says that whatever part of the county you are researching will always be on at least two maps, but often four!

The glider that came down in High Easter was recorded as having the following numbers on it: 274026 (serial number?), 29B (individual aircraft squadron number?) and 6413. The entry for the second glider is even more revealing. We know that the aircraft number in this case was 340369 and that the pilot was called Lionel Neyer with Sergeant Prupey[?]. They had taken off from Greenham Common. This would mean that this glider at least was being towed by a Dakota from the 438th Troop Carrier Group. (R.A. Freeman, UK Airfields of the Ninth then and now (London [1994]), p.16).

That’s about all we know, so over to you. What can you tell us about these events? Did you have a relative living in High Easter or Tolleshunt D’Arcy who was eyewitness to these momentous happenings? Do you know what happened to Flying Officer Neyer and Sergeant Prupey? Are you an expert on WACO CG-4 gliders and can tell us more about them? Comment below, or e-mail us to share your stories and research.