Our Learning from History Manager, Valina Bowman-Burns, is here to bring the past to life for schools. Here she tells us why census records are one of her favourite things to use in the classroom.

Valina with students from the Ursuline School in Brentwood visiting ERO

What is the census?

The census counts everyone living in the UK on a particular day and tells us a little about them – their name, age and where they live. The census is used by the government and local authorities to help plan new schools, houses and roads. A census has been taken in Britain every 10 years since 1841 (except for 1941, when everyone was busy with the Second World War). To keep everyone’s personal information safe we are not able to look at the Census for 100 years. It then becomes interesting for another reason – as a fantastic source for finding out about the past.

How do I find census records?

You can come to the Essex Record Office! Using computers in the ERO you can access all census records (and much more) via Ancestry for free. It is not possible to print from these computers, but by pressing the green ‘save’ button in the top right hand corner, you will be given the option to e-mail it to yourself.

If you’ve not visited ERO before, our short video will tell you what to expect from your first visit:

The National Archive has selected a few interesting examples of census records which you can see here – including census records for Queen Victoria, a poor London family, industry in Lancashire and a 1911 census tampered with by a suffragette!

Or there are examples here in this blog post that relate to Essex that could be useful to you. If you use them in your classroom, please let us know with a quick e-mail to ero.events@essex.gov.uk

How can I use the census in my classroom?

History: A Local history Study

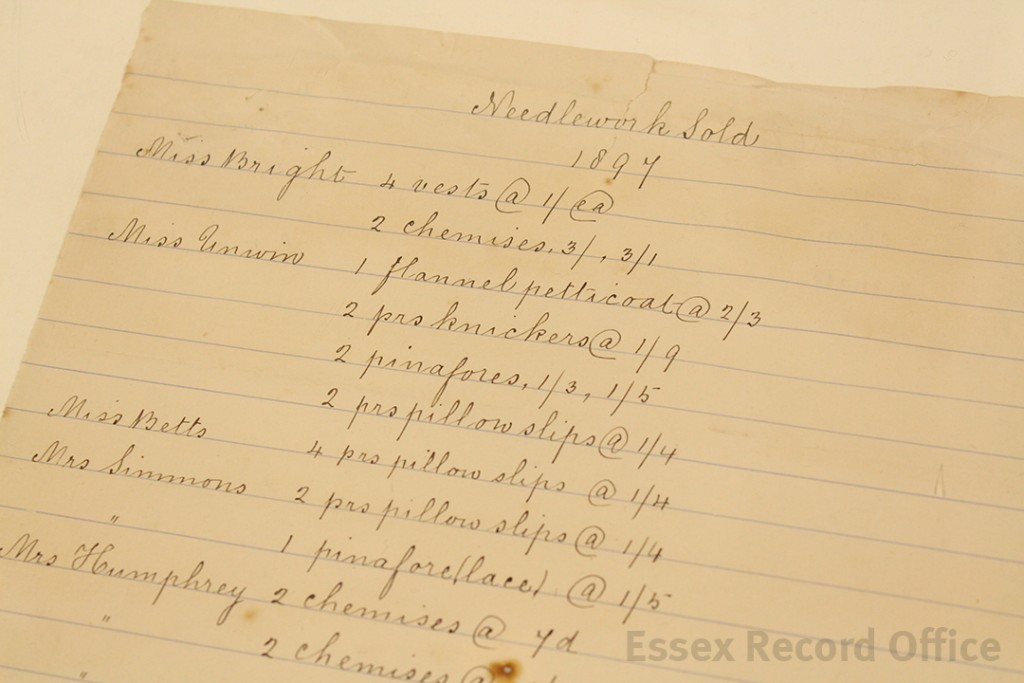

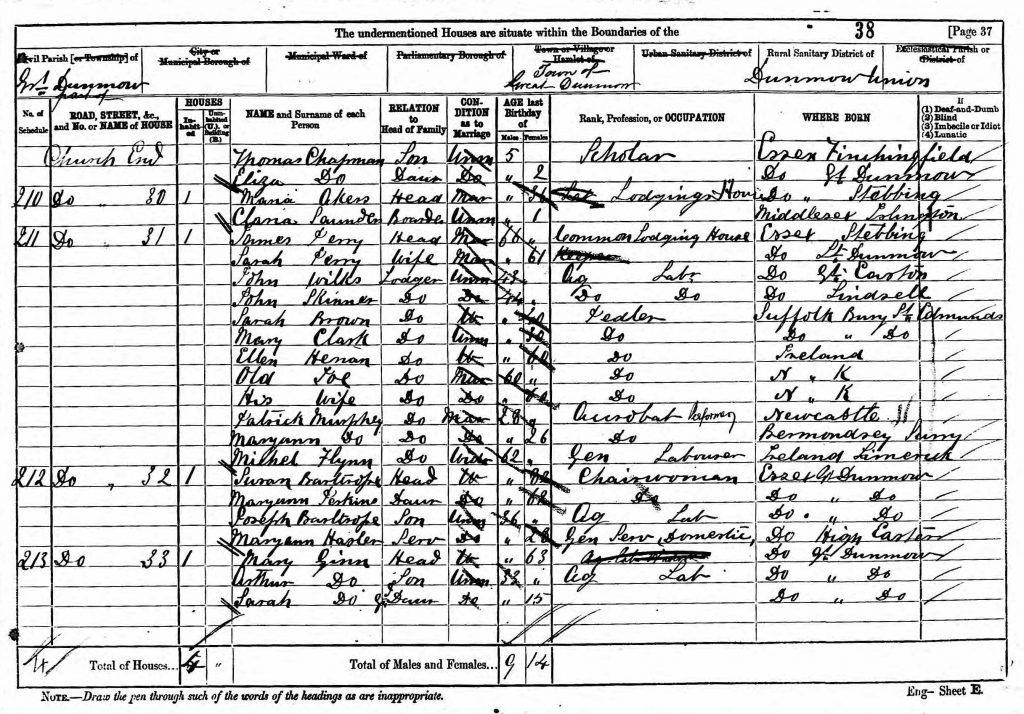

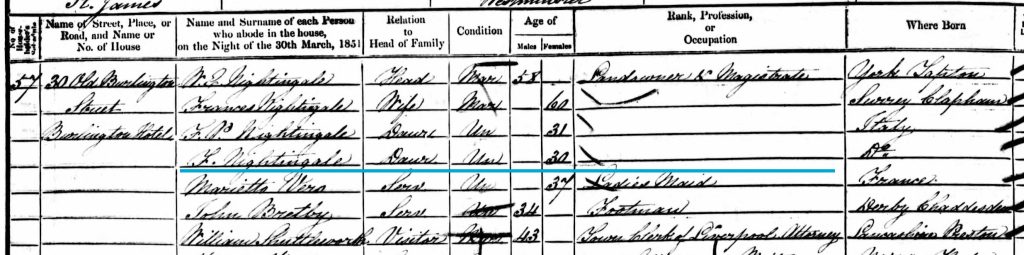

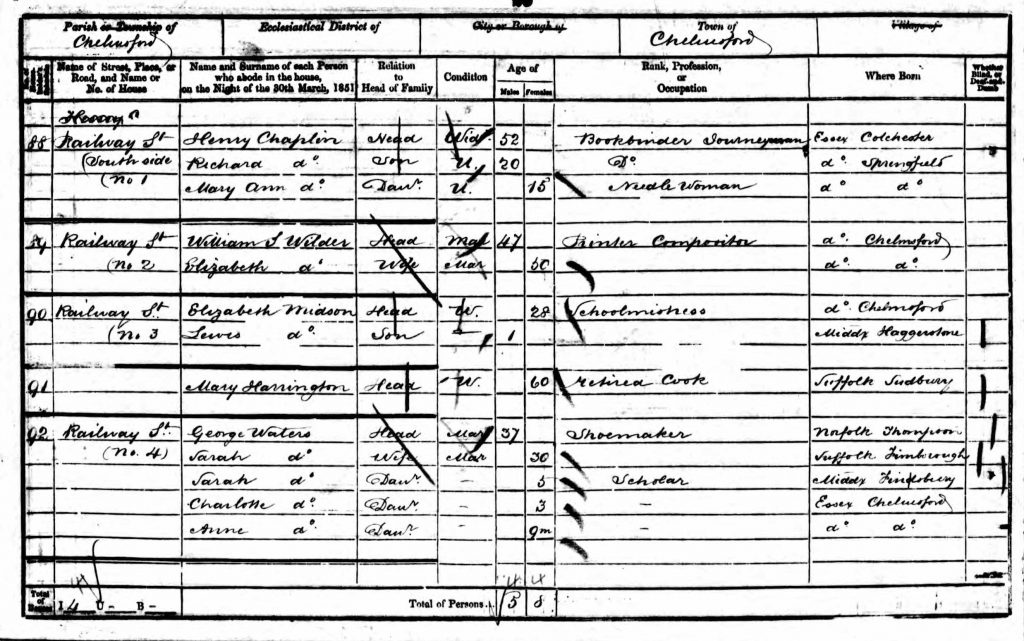

Try searching for the location of your school and discover interesting local characters from the past. To start a local history study present the children with a census page like this and ask them what information we could find out from it. Perhaps set tasks, like finding the oldest person on the page or the youngest. Can they find a scholar (a child who goes to school)?

Census records record who was living or staying at each address in the country on the night the census was taken. The first column gives the address followed by individuals’ names, marital status, ages, occupations, and where they were born.

What caught my eye on this 1881 census was a gentleman living at 31 Church End in Great Dunmow, who will forever be remembered now as ‘Old Joe’. At first I felt bad that Joe’s surname had been lost to history, until I looked down and found ‘His Wife’ – no first name or surname correctly recorded. Perhaps this could lead to a discussion about how women or immigrants (they are originally from Ireland) were viewed in Victorian Society.

History: the lives of significant individuals

Try putting the names of significant individuals from Victorian times into Ancestry. Refine your results by looking only at ‘Census and Voter Lists’.

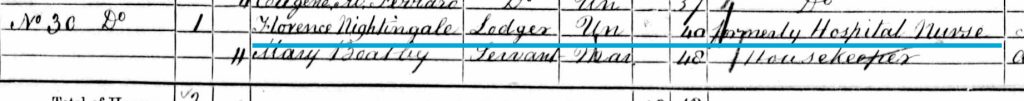

In 1851 Florence Nightingale is with her parents and the section of the Census for occupation is left blank.

In 1861 Florence Nightingale is now ‘formerly [a] Hospital Nurse’:

What happened in the 10 years in between? Can the children find out? Hint: they should come back with something like – she became a nurse, tended the wounded of the Crimean War, showed that trained nurses and clean hospitals could save hundreds of lives, set up a training hospital and is credited with founding modern nursing.

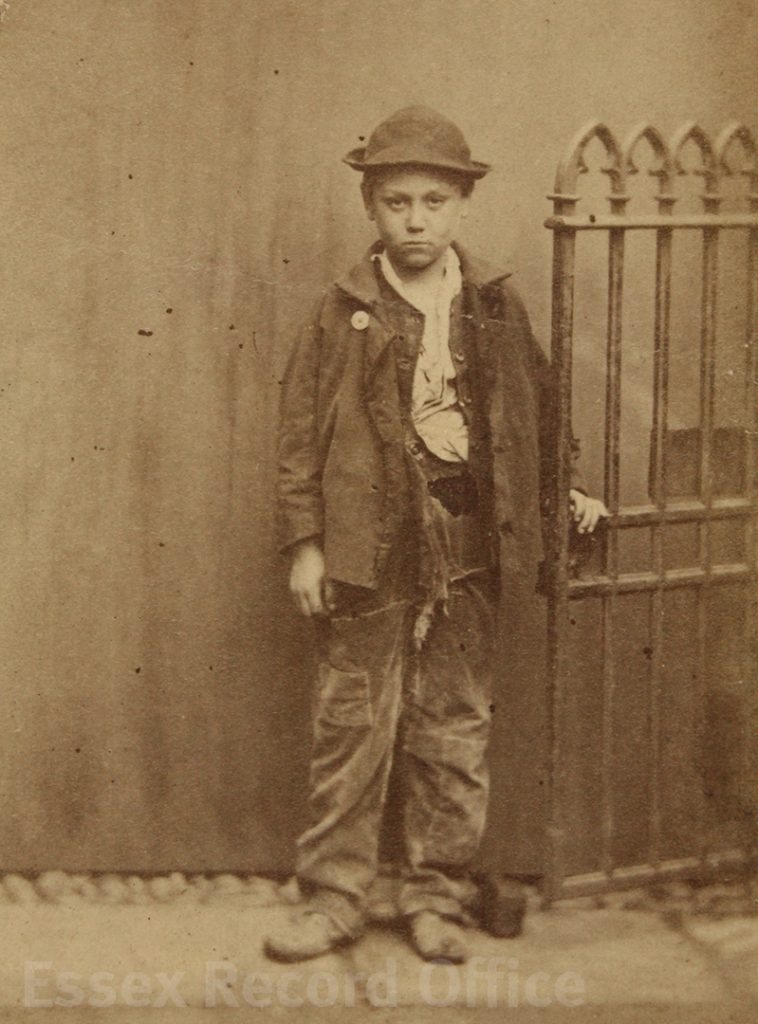

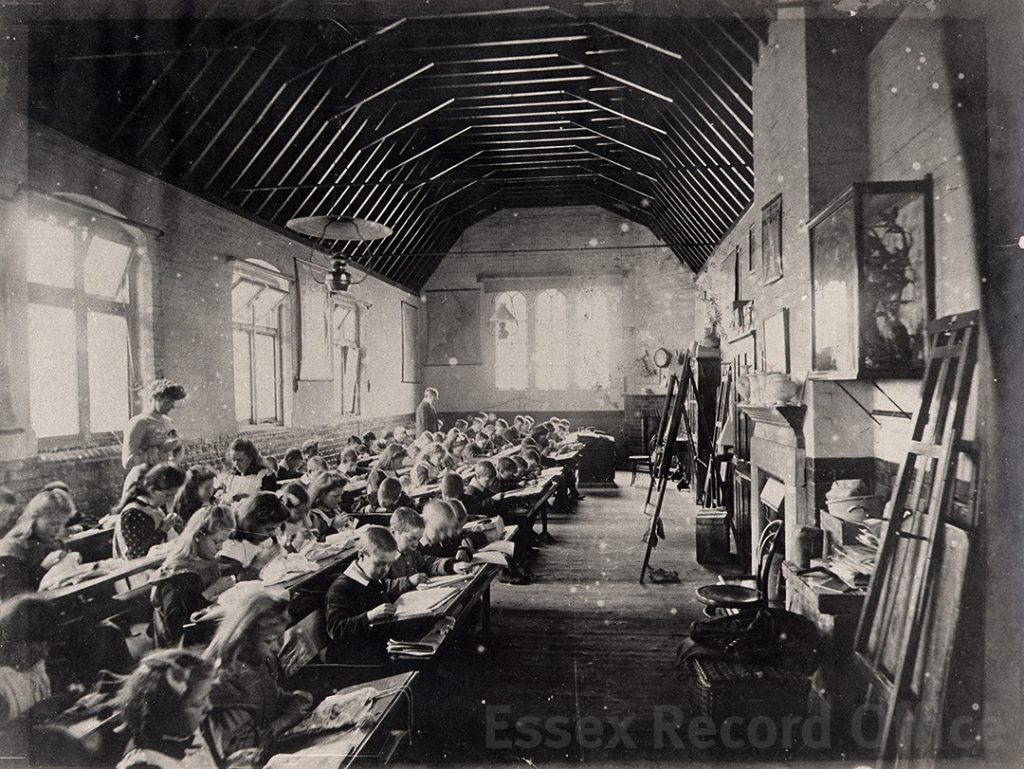

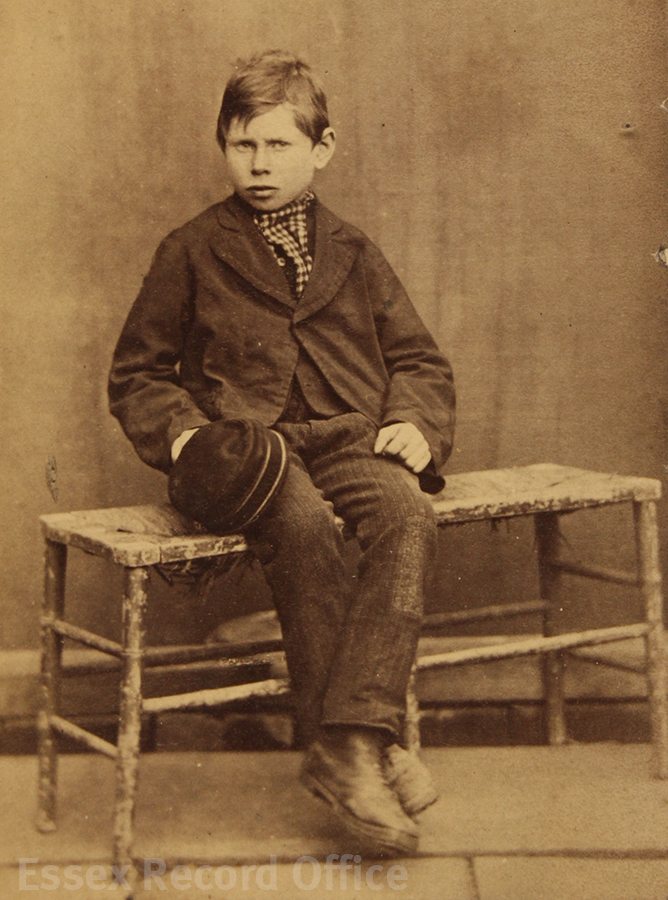

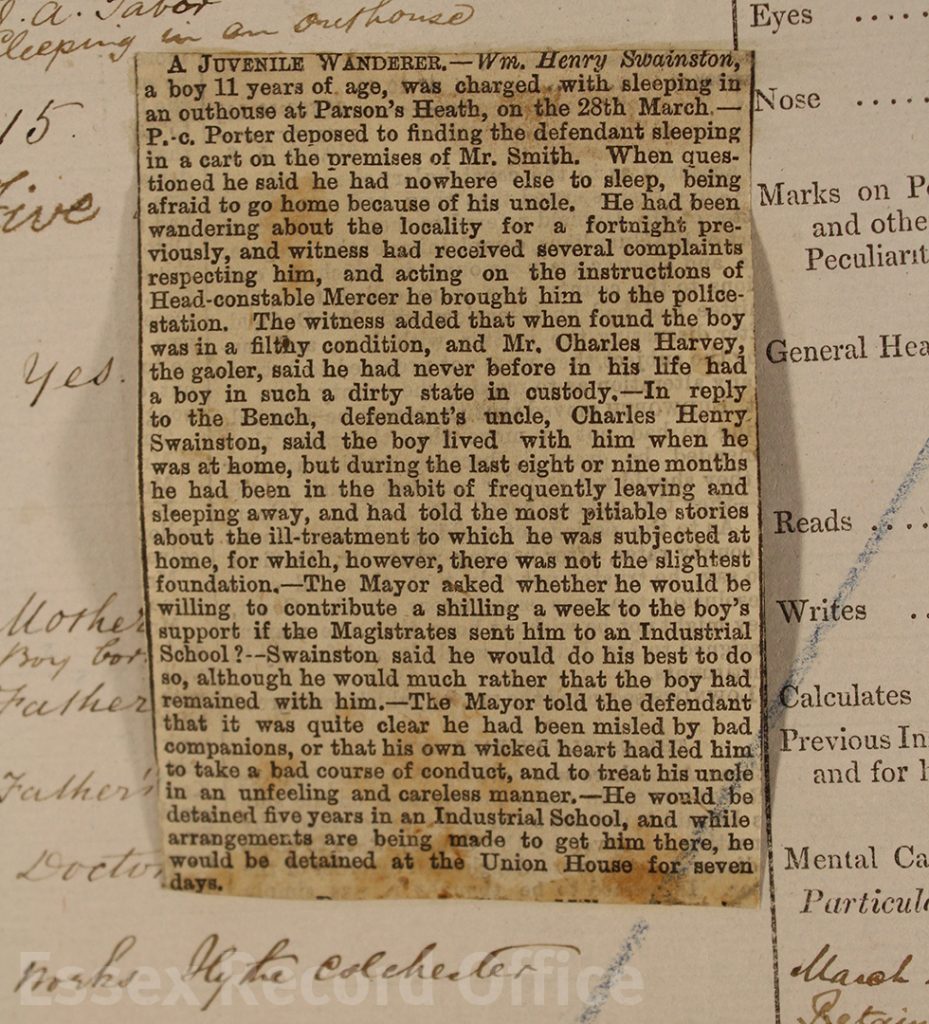

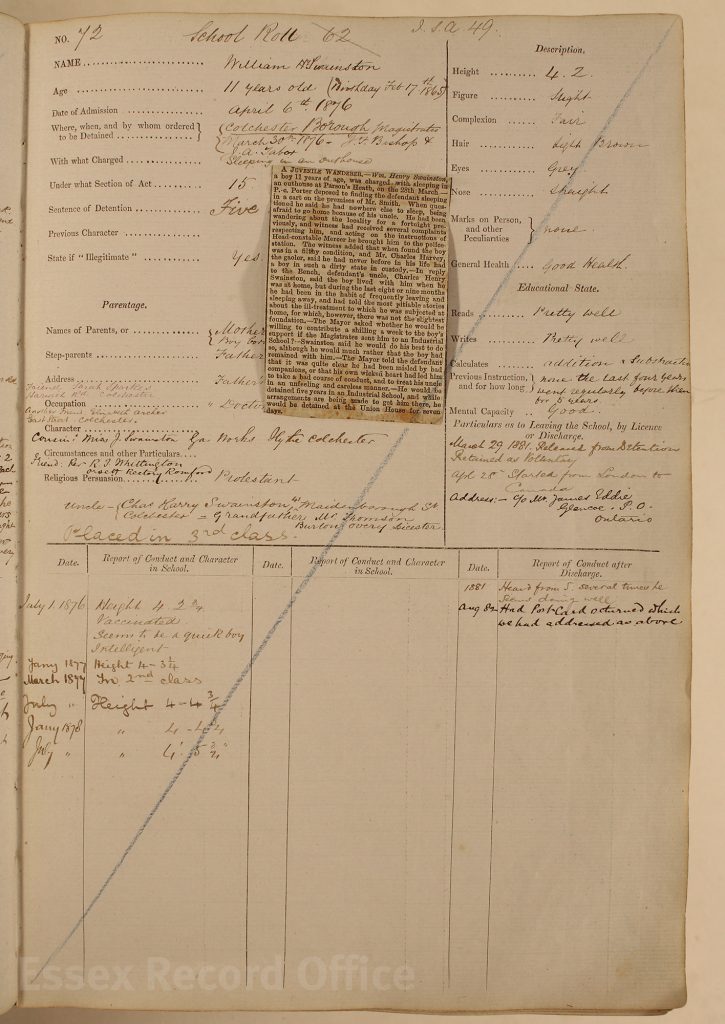

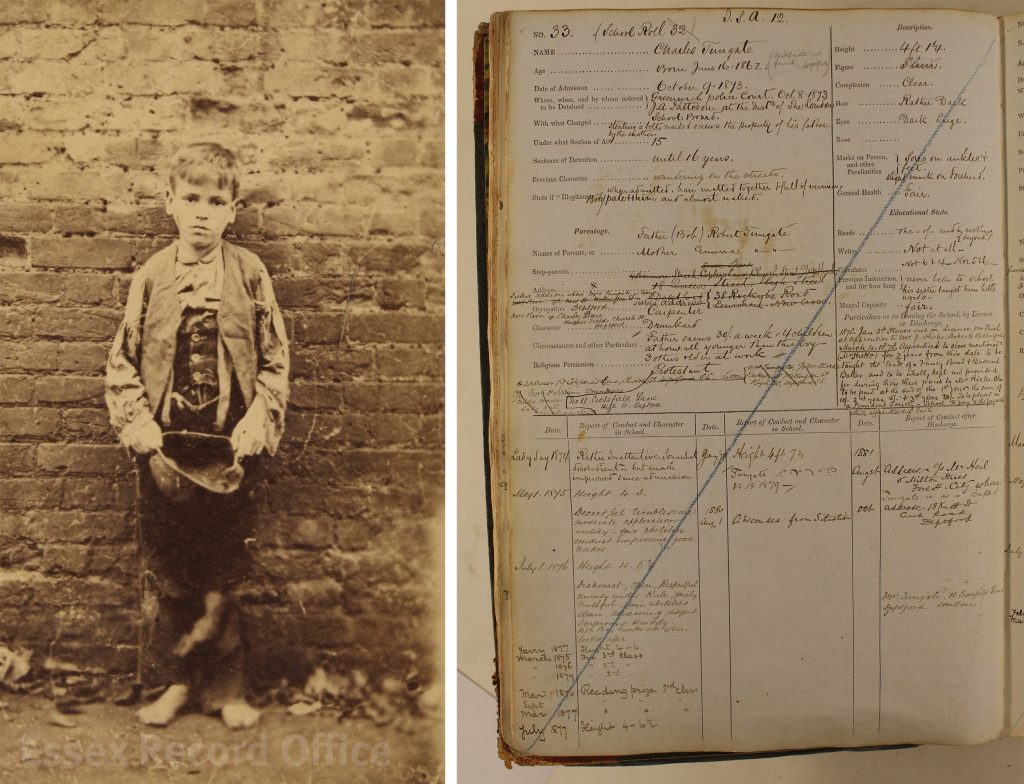

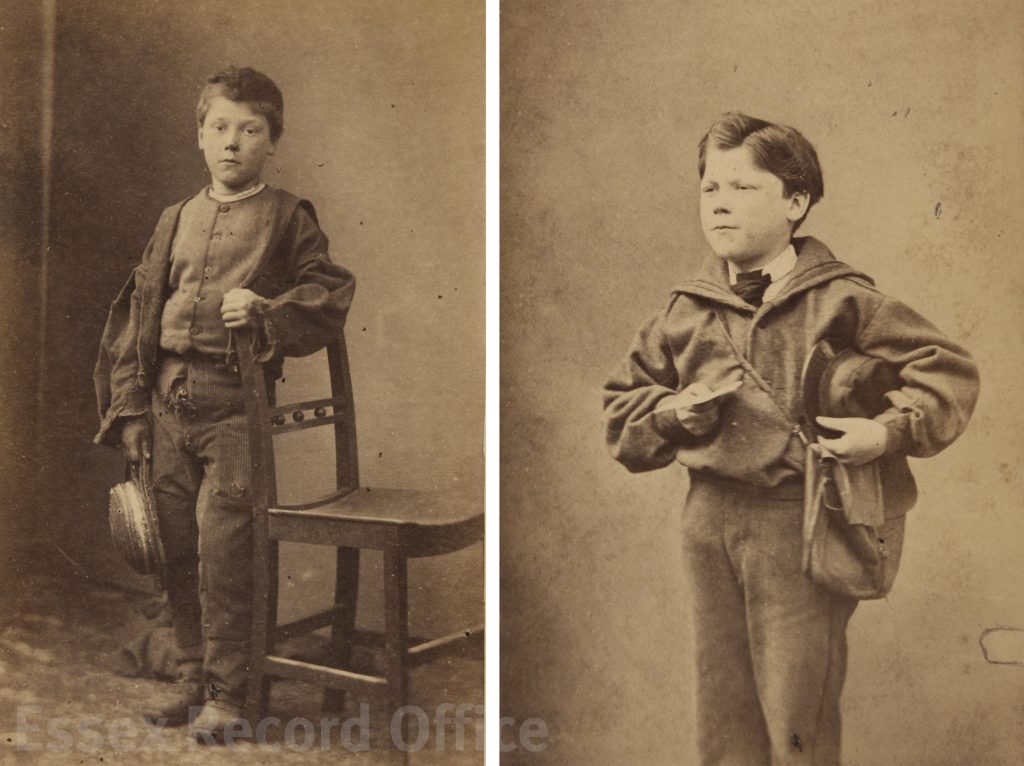

History: Children’s History

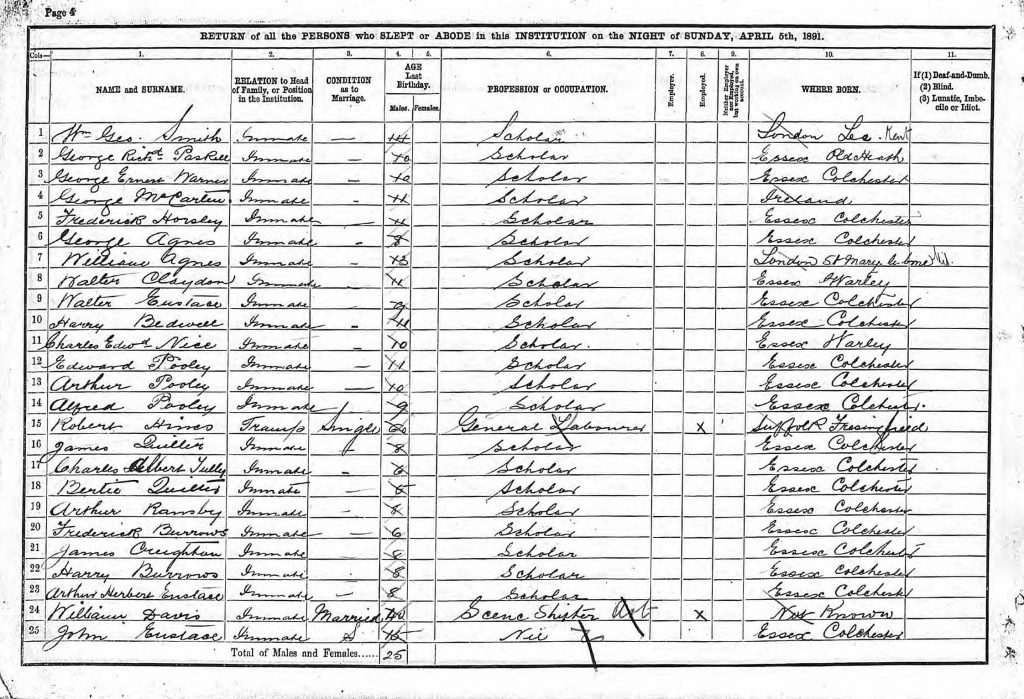

This page shows some of the boys described as ‘inmates’ at Colchester Union Workhouse in 1891.

By this time school is free and compulsory for all children and we know that North School in Colchester, nearby and newly built, accepted some of these children as students. How could this have changed these children’s lives?

What might your students discover in their local census records?

English: creative writing

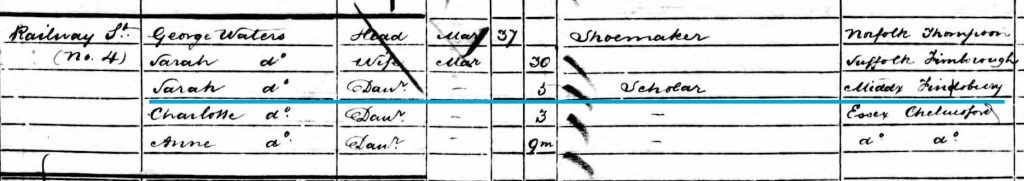

Start by challenging children’s information retrieval skills, asking what information they can gather from this 1851 census. Perhaps choose one person to be the character in a story – what do we know about them? How can we create a story from this?

Sarah’s story could start like this:

Sarah Waters awoke with a start.

“Sarah” she heard her father call urgently, “Sarah! Anne needs you!”

She suddenly realised that he wasn’t calling her, he was calling her mother. Sarah’s baby sister Anne was crying again. Sarah was glad she had woken up, because it was nearly time to school ….

Sarah made her way downstairs through her father’s shoe making workshop. The overwhelming smell of leather and glue made her feel a little dizzy, but she soon got used to it….

Sarah stepped out of her house on Railway Street. Railway Street was always dirty from the factories nearby pumping smoke from their chimneys. Sarah was on her best behaviour, as quiet as a mouse, when she walked past the house next door. It belonged to Mrs. Midson her strict, scary school teacher.

Other ways you can use Census records

The Census has amazing potential for Geography – especially showing movement and migration and how this is nothing new. Children could use a page from the census and maps to locate people have moved from. Census pages are often full of marks and dashes – where clerks have compiled information to inform government policy. In a maths lesson children could follow in their footsteps and answer questions like: how many children are there? How many people are over 60 years old? How many people are living in a different place to where they are born. An IT class gives the potential for children to present the information in fun and interesting ways – using charts and graphics.

If you want to use primary sources to bring history to life for your students, get in touch with us on ero.events@essex.gov.uk, or see what we can offer to schools on our Education Resources page.