Hannah Salisbury, Engagement and Events Manager

Researching the story of Kate and Louise Lilley, leaders of the women’s suffrage campaign in Clacton, I was put in mind of the song sung by Mrs Banks in Mary Poppins when she returns from a suffrage rally. The ‘sister suffragettes’ she sings about go ‘shoulder to shoulder into the fray’, which is just what Kate and Louise did. Kate and Louise are the best known of the Lilley family, but they were two of 10 siblings, and all three of their sisters and both their parents also took part in the campaign for votes for women.

The sisters were born in London, Kate in 1874 and Louise in 1883. Their father, Thomas Lilley, was one of the partners of the shoe manufacturers, Lilley and Skinner. The business had been begun by his father, and would stay in the family for several generations. The company became one of Britain’s largest shoe retailers, and for many years ran the largest shoe shop in the world on Oxford Street. (A selection of shoes made by the company can today be found at the Victoria and Albert museum.)

Thomas had married Mary Ann Denton in 1870, and they lived a comfortable life in London with several household servants. The help must have been useful – they had a total of 11 children together (although a son, Benjamin, died aged just 3). In 1908, Thomas had a new home built for the family in Clacton, Holland House, on the corner of Skelmersdale Road and Holland Road. (The building, somewhat extended, survives today as flats.)

At the time the family took up residence in Clacton, Kate would have been about 34 and Louise about 24. Tracing their activities through the Clacton Graphic, we can see that the sisters were extremely active within the Clacton branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), the militant organisation led by Emmeline Pankhurst. They organised and spoke at meetings, helped run the WSPU shop on Rosemary Road, organised fundraising events, and sold the WPSU newspaper, Votes for Women.

From local papers we can even get an idea of the content of the speeches that the sisters made at meetings. One such speech, made at a meeting of the local Liberal Association, was reported in the Graphic on 15 April 1911. In front of a large audience, one of the sisters (the paper doesn’t specify which Miss Lilley spoke) put forward her arguments in favour of women’s suffrage:

They could have no true democracy, unless every class was represented, and that applied quite as much to sex as class. Some might say that there were men who would always look after the interests of a woman, but men could not understand the needs of a woman, so well as the woman herself.

Women, she said, ‘wanted to feel their responsibility and help to ameliorate certain social evils, which at one time women thought it right to ignore’. She agreed with the consensus of the time that the woman’s place was in the home, but in reality ‘every morning five million women had to go out of their homes in order to keep it.’

She also spoke about wage inequality, and the different application of laws to men and to women:

it was not fair to have one law for a man and another for a woman. They asked for fair play and no favour, and as long as woman had no political status she would always be bottom dog in the labour market.

Alongside their local activities, Kate and Louise also sometimes headed back to London to take part in the campaign. Both were arrested during Black Friday in November 1910, along with hundreds of other campaigners who had attempted to gain access to the Houses of Parliament. In that instance the sisters were not prosecuted, but in March 1912 they took part in the WSPU’s campaign of smashing windows, using large pieces of flint to each break a window at the War Office. They were sentenced to two months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

The sisters were committed to Holloway prison, and were placed in cells next door to each other. After their release, Kate wrote an account of her time in prison for the Clacton Graphic (4 May 1912). She began by explaining the reasoning behind the decision to damage property as part of their campaign:

What we feel we have to do now, is to make every just-minded person, especially the men, wake up to the fact that it is their duty to help. First of all public opinion may be against us, and great anger felt. We say we would rather anger than indifference. Indifference helps no one, and after 40 years’ experience we have found coaxing and persuading of no avail. How then, are we to wake up public conscience? For any woman who is yet doubting whether our cause is really worth the sacrifice of committing an offence, which, naturally, must be very repulsive to her, imprisonment, the risk of losing her friends and social position, and, in many cases, means of earning a livelihood, besides family sacrifice she has to make, let her go to Holloway Prison. She will come up against many hard facts in life; the ordinary prisoners will become real human beings to her, and not some vague class of individuals one reads of in the newspapers. They will impress her as looking very like ourselves, except for the ugly prison dress and the hopeless expression one sees on so many of their faces. As Dr. Garrett Anderson remarked the other day: “Suffragettes go to prison as a move in the fight to life the burden from women’s lives; the other prisoners go because this burden has been too great for them.” And we must not forget the chief cause of their crime is their status and their poverty. One has plenty of time to think in Holloway.

She went on to give a description of the time she and Louise spent in Holloway, including long stretches of solitary confinement, and time in cells below ground level where they ‘suffered very much indeed from the cold’. They were allowed no letters and no visitors, but after a time were allowed two books a week from the prison library. One half-hour period of exercise was allowed per day to begin with, but as the women’s health began to suffer this was increased to two by the prison doctor.

On the subject of the hunger strike which took place at that time, Kate wrote ‘the horrors of it are still too fresh in my memory for me to feel able to dwell on any of the details’. The sisters must have taken part in the hunger strike, as on their release both were presented with hunger strike medals by the WSPU, which are today in the collections at the Museum of London.

Louise Lilley’s hunger strike medal from the Museum of London. Kate’s medal is also in their collection.

The sisters were released in early May, and returning home to Clacton they were ‘met with a most hearty welcome home from hundreds of spectators, including many women wearing the W.S.P.U. badge’ (Clacton Graphic, 4 May 1912). The crowd cheered the sisters, and they were presented with bouquets. The Graphic further reported that ‘Their suffering for the cause, which they believe to be right and just, have not damped their ardour, and they are more determined than ever to go forward’. Two photographs published in the paper show the sisters arriving at Clacton station, and being driven away in their father’s motor car.

Kate and Louise Lilley return home to Clacton after their release from Holloway prison in May 1912. One of the women on the left of the photograph, possibly one of the sisters, carries a WSPU flag. Clacton Graphic, 4 May 1912.

Kate and Louise Lilley leave Clacton station in their father’s motor car in front of a crowd of onlookers. Clacton Graphic, 4 May 1912.

The sisters must have drawn strength from the support of their family, and the fact that they also joined in the campaign. I have not found any reference to any of their brothers campaigning, but their three sisters also pop up in the Clacton Graphic.

The oldest of the sisters was Mary Hetty Lilley, born in 1872. She had married Arthur Skyes (an architect, who actually designed the Lilley’s home in Clacton, Holland House), and she lived half a mile away from her parents and sisters, at Carnarvon Road in Clacton. She chaired and spoke at local suffrage meetings, and wrote to the Clacton Graphic to express her views on things.

In April 1912, for example, an auction was held to sell a pair of binoculars, which had been confiscated from a Miss Rose, who had refused to pay her taxes as a protest against women not being allowed to vote. Mary Sykes presided over a meeting after the auction, where she ‘explained in a few words that the reason why they had met together was because they wished to express their sympathy with Miss Rose in her protest, and because they felt she was perfectly right in so doing. Women had no voice or vote, and therefore should not be taxed’ (Clacton Graphic, 27 April 1912).

In March 1912 she wrote to the Graphic in support of her sisters’ acts of breaking windows at the War Office:

Sir, – Will you allow me through your paper to contradict a wrong report issued in some of the daily papers that Miss Kate Lilley and Miss Louise Lilley had broken windows because they had been influenced by speakers. This statement is incorrect. In both cases it was pleaded that they had broken a pane of glass valued at 3s. in a Government building as a protest against the Government, and they did not wish to offer any apology.

Yours truly,

M.H. Sykes

Clacton Graphic, 16 March 1912

The other two sisters, Helen Doris Marjorie Lilley, born in 1890, and Ada Elizabeth, born in 1893, are a bit more shadowy, but they do appear in local reports as being present at suffrage meetings, and as being part of a choir dressed all in white at a WSPU meeting at Clacton in February 1912.

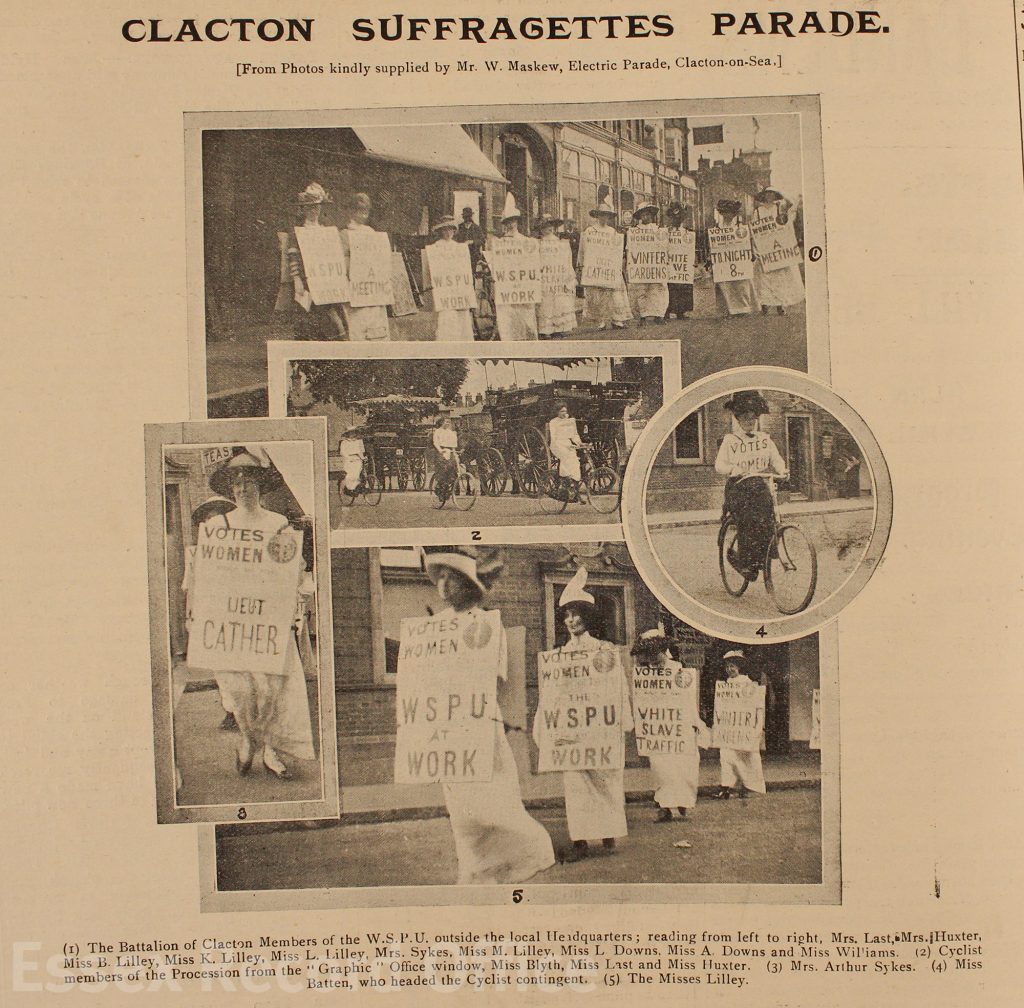

Most extraordinarily, there are even photographs of the Lilley sisters out in force, campaigning together:

This montage of photographs in the Clacton Graphic shows the Clacton branch of the WSPU at work, including all five of the Lilley sisters. All of them appear in the top photo; photo number 3 shows Mary Sykes, and photo number 5 shows the four unmarried Lilley sisters parading together in their sandwich boards.

The Lilley parents, Mary and Thomas, also got involved in the suffrage campaign. In June 1911, Mary Lilley hosted an ‘at home’ at Holland House (described in the Clacton Graphic, 10 June 1911), and she often attended suffrage meetings, and lent plants from her garden to help decorate halls and stages.

Thomas Lilley, who in addition to being a company director was a local JP and president of the local Liberal Association, was a vocal supporter of women’s suffrage. He chaired and spoke at suffrage meetings, supported women’s suffrage at Clacton town council meetings, and expressed his views in the local papers:

We are shouting, “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” What right have we to deprive a woman of her vote simply because she is a woman? For shame! This is indeed tyranny and injustice combined.

Letter to the Clacton Graphic, 13 May 1911

The family business, Lilley and Skinner, also publicly supported the campaign, decorating their window displays with ribbons in the suffragette colours of purple, white and green. They advertised in the WSPU magazine, Votes for Women, thereby financially supporting the organisation, and even made a slipper died in purple white and green.

Uncovering the extent of the Lilley family’s joint campaigning activities has been a surprising research journey (especially the bit about the purple, white and green slippers). Again the words of Mrs Banks’s song Sister Suffragettes comes to mind; the Lilley family were indeed ‘dauntless crusaders for women’s votes’.

If you would like to trace the stories of other local suffragettes, a really good place to start is the British Newspaper Archive online, which you can use for free at ERO and at Essex Libraries.

If you need to make sure your voter registration is up-to-date, you can do so here.