Hannah Salisbury, Engagement and Events Manager

Historic recipes are windows into everyday life in the past, helping us to imagine what life was like for our ancestors. Recipes tell us what people ate and drank, and how food was prepared and flavoured in a world before supermarkets, mass imports, convenience food or refrigeration, and during times of rationing. There can also be surprisingly exotic ingredients and styles of cooking, telling us something about the interconnectedness of the world in the past.

Not only do they tell us about food and drink, many historic recipe books also include instructions for making medicines, for both humans and animals. In a time with no paracetamol or antibiotics or any other modern medicines, these recipes can tell us about the health issues that our ancestors battled and how treated illnesses at home.

Speaking to the good people at the Recipes Project has inspired us to dig a little deeper into the recipes to be found amongst our collections. The project is a blog devoted to the study of recipes from all time periods and places, run by an international group of academics. Over the last few years both scholarly and popular interest in historic recipes has been growing, and the project is celebrating its fifth year by hosting a virtual conversation on the theme ‘What is a recipe?’ (2 June-5 July 2017).

The online conversation will take place on social media, so if you are interested in what might come up you can follow and join in by following the project on Twitter, and the hashtag #recipesconf.

Searching our catalogue Essex Archives Online for ‘recipe’ finds 214 results. The oldest date from the late 16th century, and the most recent from 1998. There are whole volumes of recipes, handwritten and typed, and individual sheets amongst larger bundles of papers. Some recipes are still entirely recognisable today, hundreds of years after they were written, others seem totally outlandish to modern eyes. Authors include housewives, doctors, and a cartman concerned with caring for his horses.

In terms of the question ‘what is a recipe’ posed by the Recipe Project, there is much that a dive into the ERO recipe books might be able to contribute.

With so many potential interesting avenues to pursue within these records, it is difficult to pick just one thing to write about, but I shall try to be disciplined and stick to just one of our recipe books, before highlighting a few others that are ripe for further investigation.

Mrs Elizabeth Slany’s Book of Receipts &co 1715

Elizabeth Slany’s recipe book (D/DR Z1) is one of the most substantial recipe books in our collection, and has already received some attention from authors and scholars. It has also been digitised, and images of the book can be viewed free of charge on Essex Archives Online. The first part of the book is, we believe, in Elizabeth’s own writing, and then another hand takes over later, perhaps her daughter.

Elizabeth was born near Worcester, and in 1723 married Benjamin LeHook, a factor (or agent) in the City of London. Elizabeth lived to the age of 93, dying in 1786. Her eldest daughter Elizabeth LeHook married Samuel Wegg who was the son of George Wegg of Colchester, a merchant tailor and town councillor. It was through the Wegg family that the book ultimately made its way to ERO.

Her recipe book provides fascinating insights into her life in charge of a well-to-do eighteenth-century household. Some of her recipes are for very rich food, and there is a focus on preservation of food. There are also several medicinal recipes throughout the book, none of them especially appealing. Some of the recipes are surprisingly exotic – I certainly didn’t expect to find recipes for fresh pasta or a ‘Chinese method’ for boiling rice.

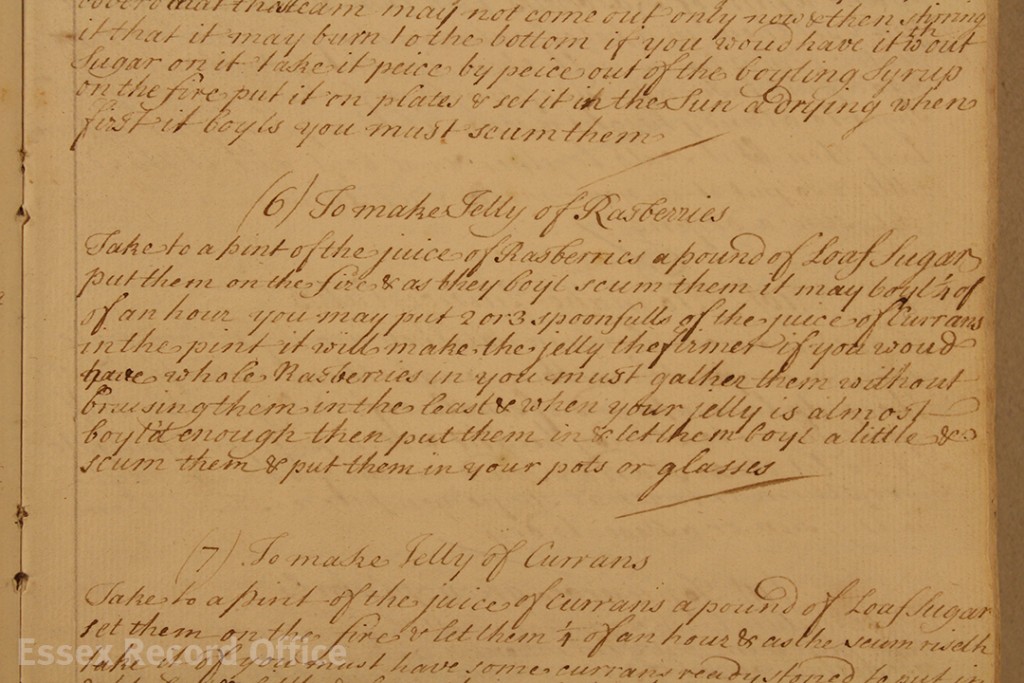

Here is Elizabeth’s recipe for preserving raspberries by making a jelly (interestingly called a jelly rather than a jam):

To make Jelly of Rasberries

Take to a pint of the juice of Rasberries a pound of Loaf Sugar put them on the fire & as they boyl scum them it may boyl ¼ of an hour you may put 2 or 3 spoonfulls of the juice of Currans in the pint it will make the jelly the firmer if you woud have whole Rasberries in you must gather them without bruising them in the least & when your jelly is almost boyl’d enough then put them in & let them boyl a little & scum them & put them in your pots or glasses

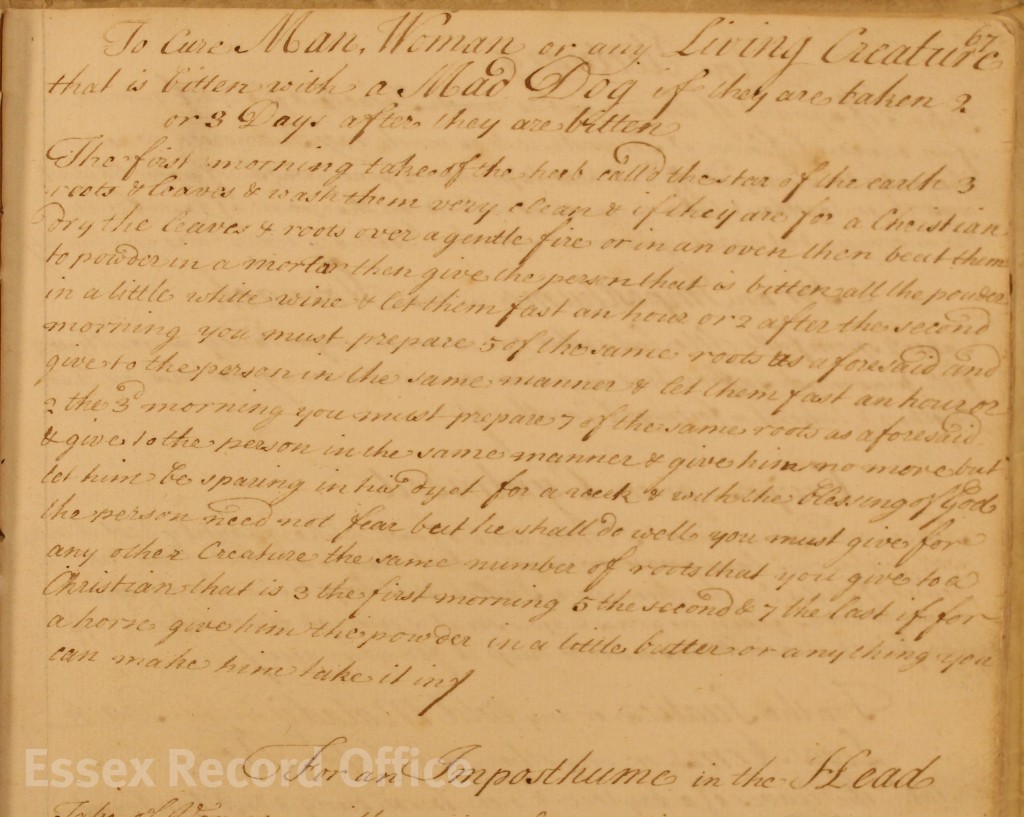

Scattered throughout the recipes for food are methods for making medicinal concoctions. Here is Elizabeth’s almost semi-magical recipe for a cure for the bite of a mad dog:

To cure Man, Woman or any Living Creature that is bitten with a Mad Dog if they are taken 2 or 3 Days after they are bitten

The first morning take of the herb call’d the star of the castle 3 roots & leaves & wash them very clean & if they are for a Christian dry the leaves & roots over a gentle fire or in an oven then beat them to powder in a mortar then give the person that is bitten all the powder in a little white wine & let them fast an hour or 2 after the second morning you must prepare 5 of the same roots as aforesaid and give to the person in the same manner & let them fast an hour or 2 the 3rd morning you must prepare 7 of the same roots as aforesaid & give to the person in the same manner & give him no more but let him be sparing in his dyet for a week & with the blessing of God the person need not fear but he shall do well you must give for any other Creature the same number of roots that you give to a Christian that is 3 the first morning 5 the second & 7 the last if for a horse give him the powder in a little butter or anything you can make him take it in.

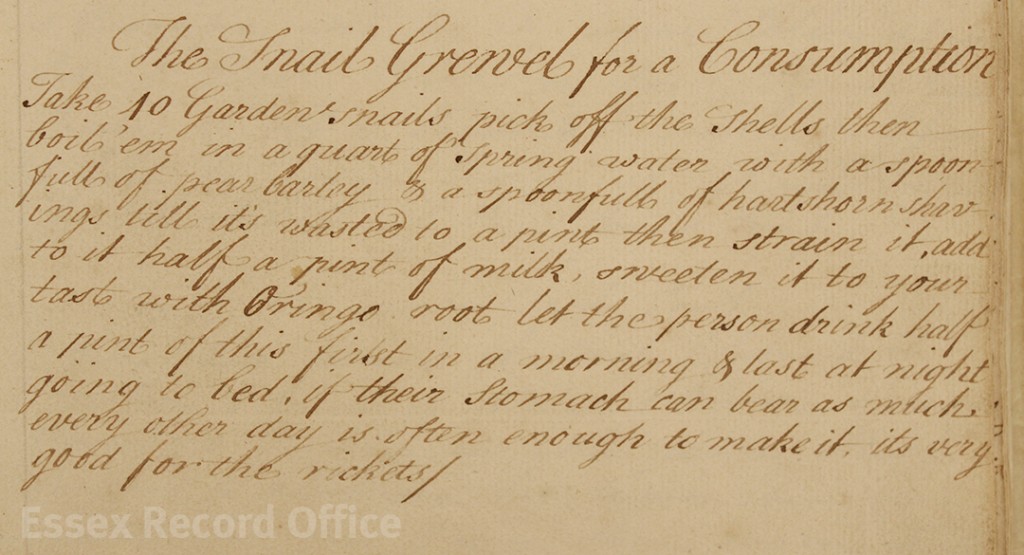

Intriguingly, there are two recipes for something called ‘snail water’, apparently a popular treatment for consumption, although here Elizabeth also recommends it for rickets. Lisa Smith of the Recipes Project tells me that this is the smallest number of snails she has seen for this type of recipe, and that they usually call for a horrifying amount of the creatures such as a peck (16 pints). Indeed, an earlier recipe in Elizabeth’s book calls for a peck of snails – perhaps this version which uses just 10 was a revision after an attempt to collect such an enormous quantity.

The Snail Grewel for a Consumption

Take ten garden snails, pick off their shells then boil ’em in a quart of spring water with one spoonful of pear[l] barley and one spoonful of hartshorn shavings, till it is wasted to a pint then strain it, add to it half a pint of milk, sweeten it to your taste with eringo root let the person drink half a pint of this first thing in the morning & last thing at night going to bed, if their stomach can bear as much, every other day is often enough to make it, its very good for the rickets

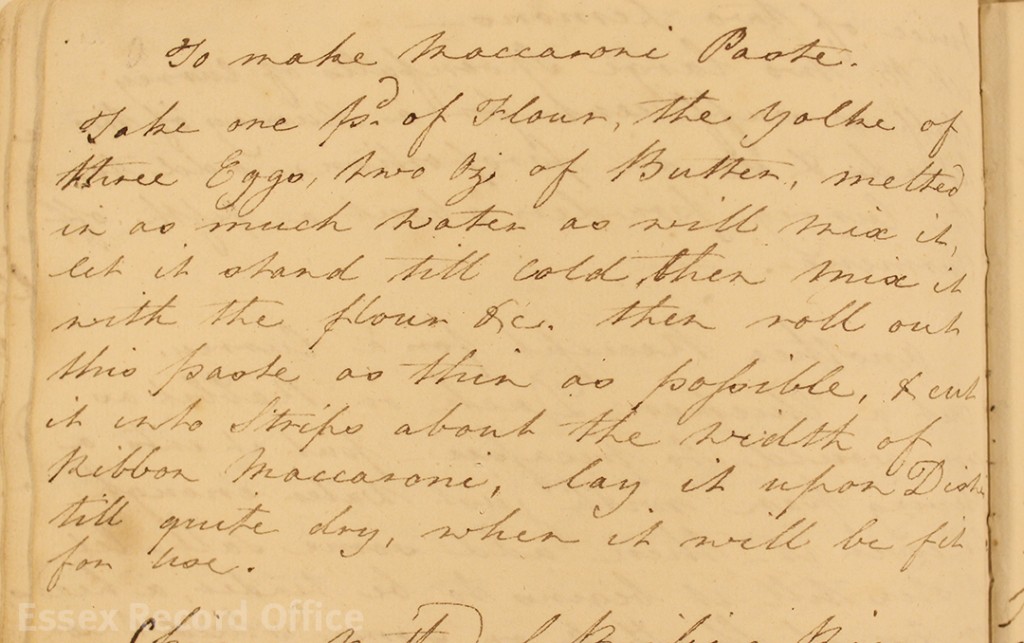

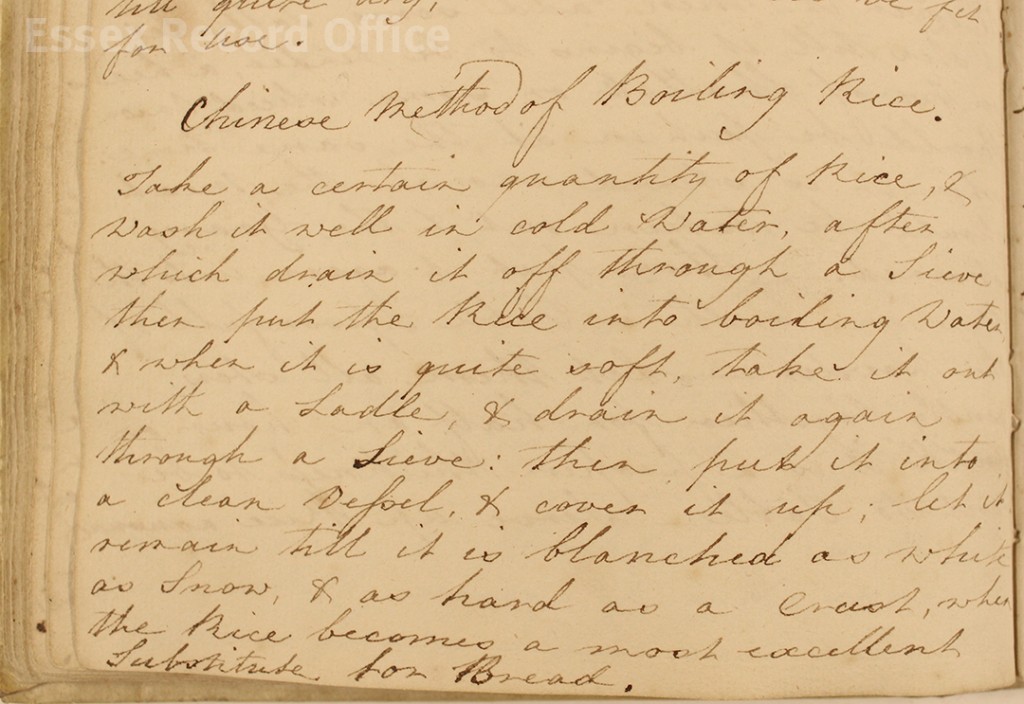

Amongst the later recipes in the book are these rather exotic ones, which have already attracted the attention of researcher Karen Bowman, who has previously written about the curry recipes in the book. On the pages following the curry recipes, we find others describing how to make fresh pasta, and a ‘Chinese Method of Boiling Rice’:

To make Maccaroni Paste

Take one pd of Flour, the yolke of three Eggs, two oz of Butter, melted in as much water as will mix it, let it stand till cold, then mix it with the flour &c then roll out this paste as thin as possible, & cut it into strips about the width of Ribbon Maccaroni, lay it upon Dishes till quite dry, when it will be fit for use.

Chinese Method of Boiling Rice

Take a certain quantity of Rice, & wash it well in cold water, after which drain it off through a sieve then put the Rice into boiling Water & when it is quite soft, take it out with a Ladle & drain it again through a sieve: then put it into a clean vessel & cover it up; let it remain till it is blanched as white as snow, & as hard as a Crust, when the Rice becomes a most excellent substitute for Bread.

There is much more that Elizabeth’s book has to tell us about life in an eighteenth-century household, but I have already written too much for one blog post so should leave it there for now. Do have a rifle through her book on our online catalogue if you want to see more.

If this little nibble at one of our recipe books has left you wanting more, there are plenty of others in our collections, such as:

- Abigail Abdy’s book of recipes, begun in 1665, including recipes for plague water and consumption water (D/DU 161/623)

- Veterinary and medical recipe book, containing 40 formulas for medicines for horses and 24 for humans, c.1899 (D/DU 892/1)

- Recipe book for use in British Restaurants and Canteens, with hints on catering in view of rationing restrictions, including adding carrots or beetroot to jam in puddings. All quantities are based on catering for 100 people (D/UCg 1/7/10)

A search for ‘recipe’ on Essex Archives Online will bring up even more recipes to explore – do let us know what you find.

Very interesting. The missing word in the rice recipe is vessel.