Back in April, we held an event to commemorate the 80th anniversary of when the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) reached peak strength in Essex in the run-up to D-Day, Welcome to Essex. We were delighted that Dr Catherine Pearson gave a fascinating talk based on the diary entries of E.J. Rudsdale, about relations between the Americans and the Essex locals. We are even more delighted that Dr Pearson has kindly taken the time to turn her talk into a blog post. To mark the anniversary of D-Day, we have also recorded an edited version of Rudsdale’s entry for that momentous day.

Eighty years ago, in the midst of the Second World War, Essex had become home to thousands of US service personnel in readiness for the allied invasion and liberation of occupied Europe. Essex Record Office holds a contemporary diary account by Colchester Museum curator, E.J. Rudsdale (1910-1951), which records the impact of the arrival of the USAAF in Colchester and the nearby USAAF airfields of Boxted and Wormingford.

Rudsdale was seconded from Colchester Museum in 1941 to become Secretary of the Lexden and Winstree District Committee of the Essex War Agricultural Committee for the duration of the war. This gave him a valuable insight into the development of the American airfields because the USAAF commandeered agricultural land from the Essex War Agricultural Committee for the construction of the airfields at Boxted and Wormingford.

Owing to the drive to increase agricultural production for the war effort, the Essex War Agricultural Committee viewed the takeover of farmland for airfields with some trepidation and a degree of antagonism. This is evident from Rudsdale’s first official encounter with USAAF personnel:

April 29 1943

Went to the Office of the Clerk of the Works [at Wormingford Aerodrome], … and found to my surprise that it was not Air Ministry men whom I was to meet but United States Air Force Officers. Two of them I had seen [in Colchester], a Major Miller and a Lieutenant Walters. … Miller … looks the typical “small-town” American one sees in so many films, his worn, lined face surmounted by rimless glasses. … Walters was dark and dapper … The arrangement was that we all went off in two cars, driven by English girls in pseudo-American uniform, to inspect sites for a shooting butt. I was supposed to say whether the site was suitable from an agricultural point of view.

As we moved off along the concrete perimeter road, through a desert of derelict farm land, I remarked “Well, there has certainly been a change since I was here last. Why, you’ve changed the whole landscape.” I said this quite innocently, but at once Major Miller turned on me and snapped out “Well, wouldn’t you rather have us here than the Germans?” … He went on “We can’t bother about the convenience of a few British farmers, you know.” It was obvious from his manner that he had already had a good deal of criticism since he came to England.

(D/DU 888/26/3 pp.568-571)

It was clear that greater accommodation on both sides was necessary for establishing more harmonious relations and Rudsdale’s next encounter with American personnel was of a warmer nature. On 1 July 1943, he was called to Boxted Airfield to discuss the USAAF’s further plans for the site and wrote:

… Major Anderson of the USAAF … was very affable. … [He] looked at the lay-out plan, and said: “This is a mean site, I guess this is the meanest site I’ve ever seen.” Then we went into various details, and their final requirements were not unreasonable. …

We rode all over the site in two jeeps – old [Gardiner] Church [a member of the Lexden and Winstree District War Agricultural Committee] was very tickled, and said “These are the things for farming, boy! I’m going to have one o’they after the war!”

(D/DU 888/26/4 pp.819-822)

In 1944, Rudsdale visited Wormingford Airfield in order to rescue historic timbers from Harvey’s Farmhouse, which was demolished in the course of the aerodrome’s expansion, and his diary entry recorded:

January 15 1944

Thick fog this morning, and bitterly cold. … we got busy loading the moulded ceiling timbers, with the help of three Land Girls. The driver ventured onto the mud, against my advice, and soon the lorry was stuck fast, so that no amount of tugging could release it. Took one of the Land Girls … and went off to see if we could get any help. It was very strange to wander about among planes and lorries in the thick fog, hearing the accents of America and Ireland intermingled as we passed groups of mechanics or labourers.

Found the big hanger, which thrilled the Land Girl a good deal – “Well,” she said, “I never thought I should see the inside of a hanger.” Neither did I.

… The sergeant could not do enough for us, and within a matter of minutes [an] enormous tractor, … was ploughing through the mud towards us. … [a] wire was attached to the lorry’s front axle, the motor raced, and out she came, … leaving behind four pits almost as big as graves, where the wheels had been.

By this time … we … set off back to Colchester… first collecting one of the Land Girls from the pilot’s seat of a nearby ‘plane, where a sergeant was showing her the controls. …

(D/DU 888/27/1 pp.48-51)

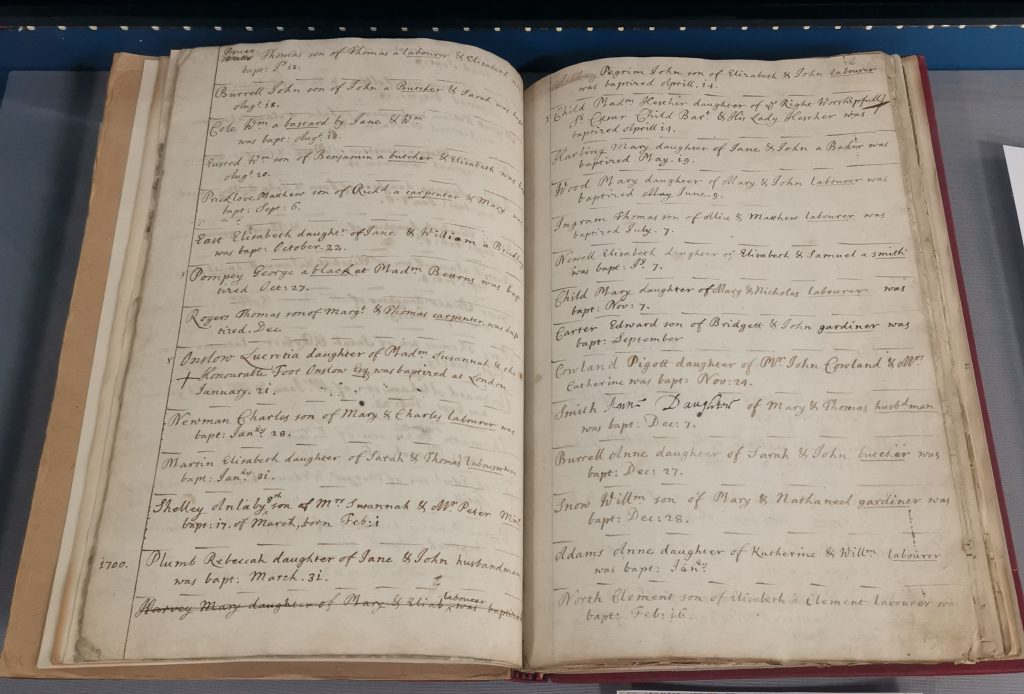

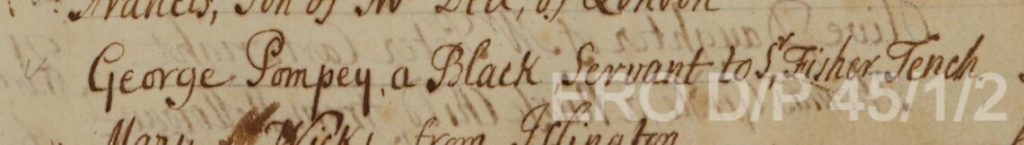

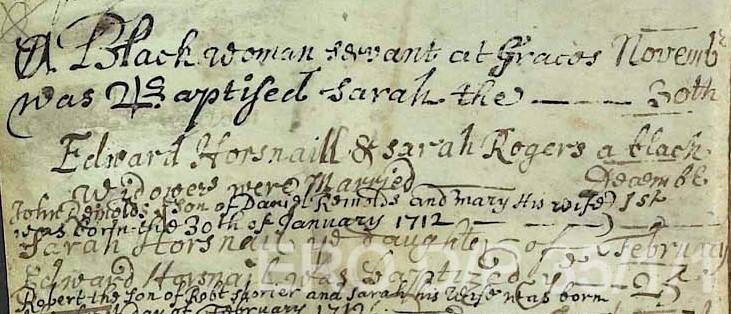

Rudsdale also discussed the black servicemen and women who formed part of the American Forces and were regularly seen in Colchester. African-American service personnel were employed as drivers or military policemen or worked in supplies or in the construction of aerodromes. Under American segregation orders, black troops had their own club in Priory Street in Colchester, and white troops had a club in Culver Street. However, Rudsdale and his fellow curator, Harold Poulter (1880-1962), regularly talked to the black service personnel. On 10 June 1944, Rudsdale wrote that he had ‘called at the American Red Cross Club in Priory Street’ to deliver a message from Poulter to a Miss Marie Wall, who Rudsdale described as a ‘delightful’ black servicewoman ‘of about 25’ and went on to record that they ‘Talked for an hour or so’. (D/DU 888/27/3 p.491).

Colcestrians do not appear to have been in favour of American segregation orders. Rudsdale noted black and white Americans troops sitting in the same café in Colchester in February 1944, albeit at separate tables (D/DU 888/27/1: 25/2/1944 p.182). He also recorded that black service personnel staged a week’s theatre performance at Colchester Repertory Theatre in December 1944 (D/DU 888/27/5: 30/11/1944, p.820).

American servicemen on the Castle Walls, Colchester Castle, 1944. Harold Poulter, Curator of Hollytrees Museum, is in the centre of the photograph and Lieutenant Stich, Public Relations Officer at Wormingford Airfield, is on the left (D/DU 888/27/4 p.590)

The positive developments in Anglo-American relations in Colchester were made apparent in late 1944, when the Americans were invited to stage an exhibition at Colchester Castle. The display was the brainchild of Lieutenant Stich, Public Relations Officer at Wormingford Airfield and Harold Poulter, the Curator of Hollytrees Museum. The exhibition, entitled The England that America Loves, featured paintings and photographs of English scenes that had appealed to the American troops during their time in the UK (Colchester Museum and Muniment Committee Report 1948, pp.5-6).

An American serviceman and a woman visitor at The England that America Loves exhibition at Colchester Castle Museum, 1944 (Courtesy of Colchester and Ipswich Museums)

Visitors to The England that America Loves exhibition at Colchester Castle Museum, 1944 (Courtesy of Colchester and Ipswich Museums)

The shared experience of war was a further factor in bringing the allies closer together. One of those who participated in the Castle exhibition, Lieutenant-Colonel Elwyn G. Righetti, a pilot at Wormingford, lost his life on 17 April 1944 when his plane went down over Germany. A party to celebrate his 30th birthday had been prepared for him back at the airbase to which he never returned (Benham 1945, p.57). Such tragic incidents increased the local community’s gratitude for the sacrifices being made by the Americans.

Pilots of the 55th Fighter Group, Wormingford Airfield, meeting the Mayor of Colchester at The England that America Loves exhibition at Colchester Castle Museum, 1944 (Courtesy of Colchester and Ipswich Museums). Left to right: Lt-Col Elwyn G. Righetti (who lost his life on 17/4/45 over Germany, aged 30); Col George T. Crowell; Arthur W. Piper, Mayor of Colchester; Col Joe Huddleston; unknown.

With the arrival of VE Day on 8 May 1945 and the close of hostilities in Europe, there were opportunities for the troops to relax and local people were invited to visit the US airbases. As the USAAF prepared to leave Colchester in July 1945, they presented Colchester Corporation with a silver rose bowl to thank the town for its hospitality and this remains part of the City’s regalia today.

The presentation of a silver rose bowl to Colchester Corporation to thank Colchester’s inhabitants for their hospitality towards American service personnel, 1945 (Courtesy of Colchester and Ipswich Museums)

After the war, American veterans made regular visits to the UK to remember their time in Essex and to pay homage to fallen comrades. One ex-serviceman wrote to the curator of Colchester Castle in 1988, that the veterans ‘would like to see a museum exhibition depicting their life as it was here in Colchester from 1943-1945 … with its bitter sweet memories’. (Colchester and Ipswich Museums, Historic Displays & Exhibitions file, Lewis to Davies, 22/11/1988). Colchester and the Castle Museum, therefore, remained as touchstones for the veterans’ wartime experiences in Essex.

Colchester Castle Museum, 1944, a photograph by Lieutenant Stich, USAAF. Note the air raid shelter sign in the rose bed (D/DU 888/27/4 p.586)

In this excerpt from Rudsdale’s diaries, read by the ERO’s Neil Wiffen, he recalls 6 June 1944 – D-Day – from being woken up by planes warming up at Wormingford Airfield at 2am to hearing the King’s speech on the radio at the end of the day. You can read a transcript here.

Dr Catherine Pearson will be speaking to us about E.J. Rudsdale at ERO Presents on Tuesday 3rd September. Book your tickets on our Eventbrite page.

References

Primary sources:

Rudsdale, E.J., (1939-1945). ‘Colchester Journals’, Essex Record Office, ERO D/DU 888.

Colchester and Ipswich Museums, ‘Historic Displays and Exhibitions’ archives.

Secondary sources:

Beale, A., (2019). Bures at War: A Hidden History of the United States Army Air Force Station 526.

Benham, H., (1945). Essex at War, Essex County Standard: Colchester.

Pearson, C., (2010). E.J. Rudsdale’s Journals of Wartime Colchester, The History Press: Stroud.

8th Airforce Historical Society: https://www.8thafhs.org/research/ Accessed 16 April 2024.

Archive of the American Air Museum in Britain, Imperial War Museum Duxford, including the Roger Freeman Collection of USAAF images: https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive Accessed 16 April 2024.

Black GIs in Britain: https://mixedmuseum.org.uk/brown-babies/black-gis-in-britain/ Accessed 16 April 2024.

Colchester Museum and Muniment Committee Report 1944-1947 (1948): https://www.esah1852.org.uk/library/files/C0938954.pdf Accessed 15 May 2024.

US Black Servicemen in Suffolk in WW2: https://www.suffolkarchives.co.uk/sharing-suffolk-stories/us-black-servicemen-in-suffolk-during-wwii/ Accessed 16 April 2024.

USAAF Airfields: Guide and Map, East of England Tourism. http://www.ukairfields.org.uk/uploads/7/0/8/5/7085670/usaaf_airfields_guide_and_map.pdf Accessed 16 April 2024.

Recordings of D-Day experiences in the Essex Sound and Video Archive:

SA 1/455/1: ‘Essex at War’, BBC Essex programme, 1989; role of Southend and Leigh in D-Day

SA 1/634/1: Interview with John Hayes on BBC Essex, 1990; serving as an RAF Ground Technician at Southend airfield in the run up to D-Day

SA 1/1183/1: Interview with Clifford Pontbriand on BBC Essex, 1994; American D-Day bomber pilot at Stansted

SA 8/540/1 (Colchester Recalled reference 2057): Interview with Alfred Douglas Chignall, 1989; serving in the Royal Navy during D-Day

SA 8/948/1 (Colchester Recalled reference 2208): Interview with Fred Ramplin, 1990; serving in the army during D-Day

SA 8/14/1/6/1 (Colchester Recalled reference 2141): Interview with Harry Finch, 1990; involvement in the D-Day invasion, including movements of warships

SA316 (Colchester Recalled reference 1272-4): Interview with Lance Corporal Ken Lambert, 1994; involvement in D-Day with the 8th Battalion Middlesex Regiment

SA443 (Colchester Recalled reference 1621): Interview with Fred McIntosh, flying instructor, at a reunion of American airmen, 1992; covered the Arnhem parachute drops.

SA779 (Colchester Recalled reference 1532): Interview with Arthur Parsonson, 1988; NCO with 431st Bty, 147th (Essex Yeomanry) Field Regt, Royal Artillery, 8th Armoured Bde during D-Day (see also Imperial War Museum interview)

SA 20/1138/1: Interview with Geoff Barsby, 1983; serving in the Royal Navy during D-Day, covering the Canadian landings, escorting the battleship Nelson, and being based off Normandy

SA 20/1533/1: Interview with Jack Nelson Wise, 1981; serving in the Royal Navy, operations in preparation for D-Day, MTBs

SA 20/1/47/1: Interview with Howard Stone, 1984; serving as a Telegrapher Air Gunner in the Fleet Air Arm during D-Day

SA 20/1/22/1: Interview with Sylvia Ebel, 1983; serving in the ATS during D-Day, D-Day preparations at Eastleigh, near Southampton

SA 79/1/1/1: Interview with Alec Hall, 2016; serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps during D-Day; stationed along the east coast of England, then travelling to Arnhem by glider

SA 79/1/3/1: Interview with Alfred Smith, 2016; serving in the Royal Army Service Corps during D-Day, driving his lorry onto Gold Beach, Normandy

SA 79/1/4/1: Interview with Ken ‘Paddy’ French, 2016; serving in the RAF during D-Day, flying over American troops at Omaha Beach

SA 79/1/5/1: Interview with Alfred Fowler, 2016; serving in the Royal Navy during D-Day; being involved in the dummy convoy to Norway

SA 86/1/3/1: Interview with Ron, 2017; serving in the Royal Navy during D-Day, escorting HMS Belfast on HMS Ulster at Gold Beach

SA634: Interview with Olive Redfarn, 2012; working on HMS Leigh, printing instructions for D-Day in the weeks beforehand [including her own diary entry of the 6 June 1944]