Whether you are tracing your ancestors or researching social or demographic trends, marriage records can provide valuable information. A project we are currently undertaking at ERO is making some of these records easier to find than ever before.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, couples could be married either by Banns or by Licence. Most couples married by Banns. As today, the Banns would be read on three consecutive Sundays in the parish in which the couple intend to marry, and in both of their home parishes if these were different. When the Banns were read, members of these communities were invited to reveal any impediment which would prevent the couple from legally marrying.

In certain cases, however, couples did not qualify to be married by Banns and had to apply for a marriage licence from the local Archdeacon instead. This would be the case if either party was under 21 years of age, if the marriage needed to be formalised quickly, or where the couple was marrying away from their home parish(es).

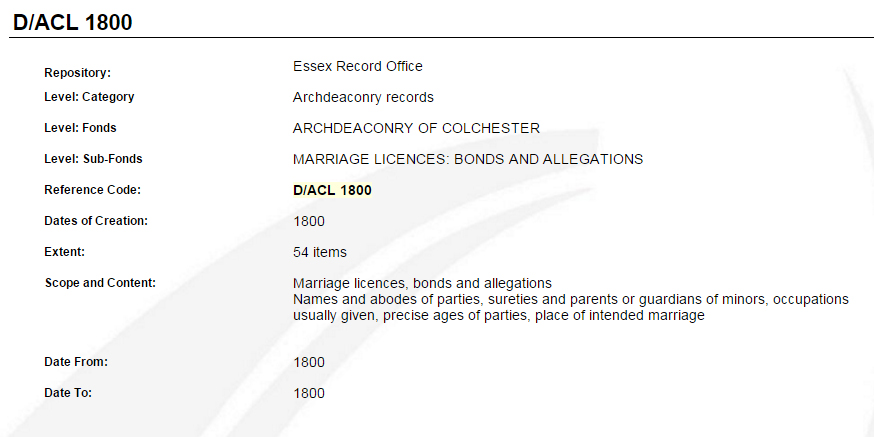

There are several thousand of these records surviving in ERO’s collections. They are grouped by which Archdeaconry they were issued by, and then by year. A typical catalogue entry at the moment looks like this one for licences issued by the Archdeaconry of Colchester in 1800, a bundle of 54 licences:

There is a paper index to these records in the ERO Searchroom, but we are currently working on a project to make all of these records searchable by name on our online catalogue, Seax. This will make them much easier for researchers to find.

The records comprise three different kinds of documents – Allegations, Bonds, and the licence itself:

- Allegations – the couple, or just the groom, would have to swear that there was no just cause or impediment to them marrying

- Bonds – a bond for a sum of money would accompany the Allegation. The money would be payable if it turned out that the marriage was contrary to church law

- The Bond and Allegation were retained by the Archdeacon who issued the actual licence to the groom. The groom would then present it at the church where the couple was to be married

The licences themselves do not often survive, but the Bonds and Allegations mostly do.

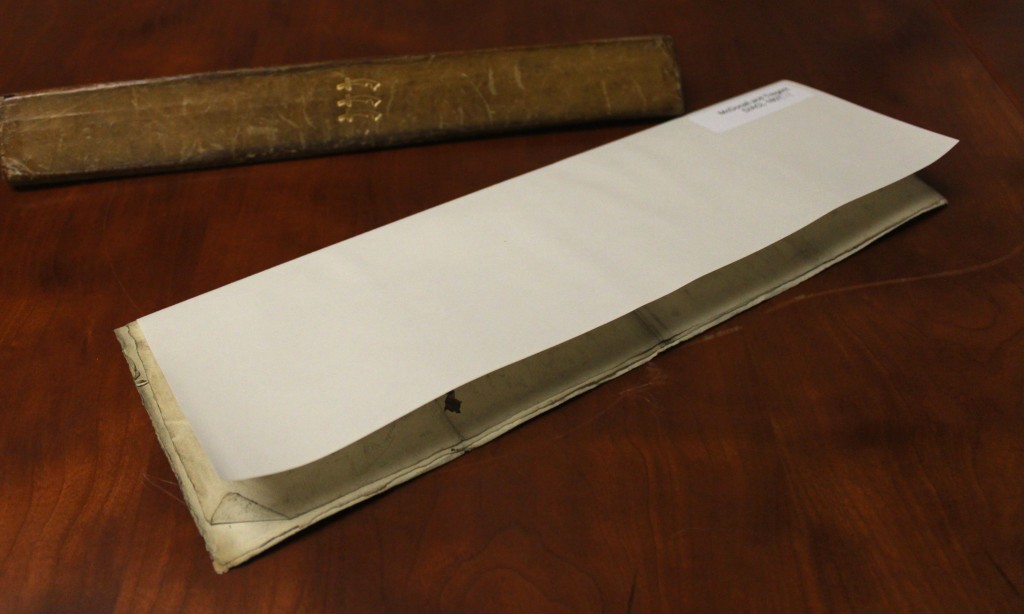

All marriage licence bonds and allegations are individually wrapped and labelled with the name of the couple they relate to (D/ACL 1807/28)

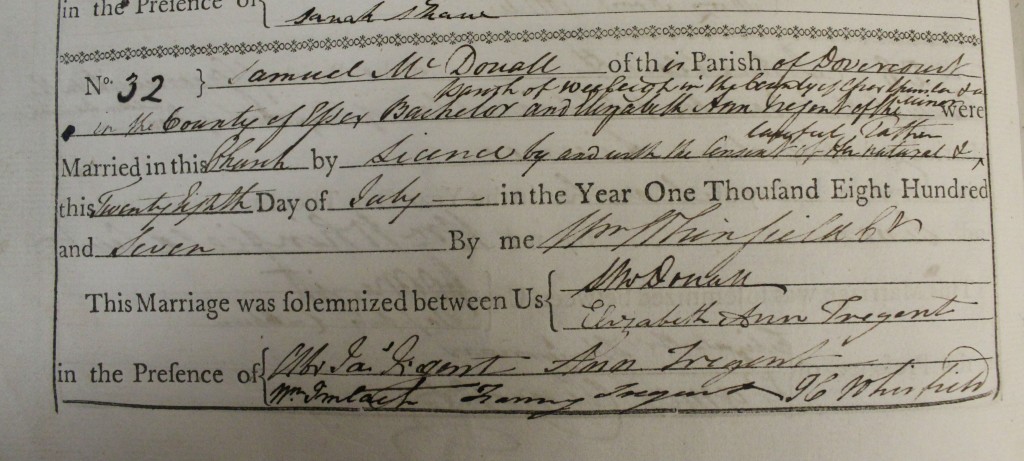

To show how marriage licence records can help to tell someone’s story, we have been looking into one of the more interesting characters who appears in them, Captain Samuel McDouall. He and his fiancée, Elizabeth Ann Tregent, were granted a licence to marry on 27 July 1807. The couple needed a licence because Elizabeth was only 19, and needed the consent of her father to marry.

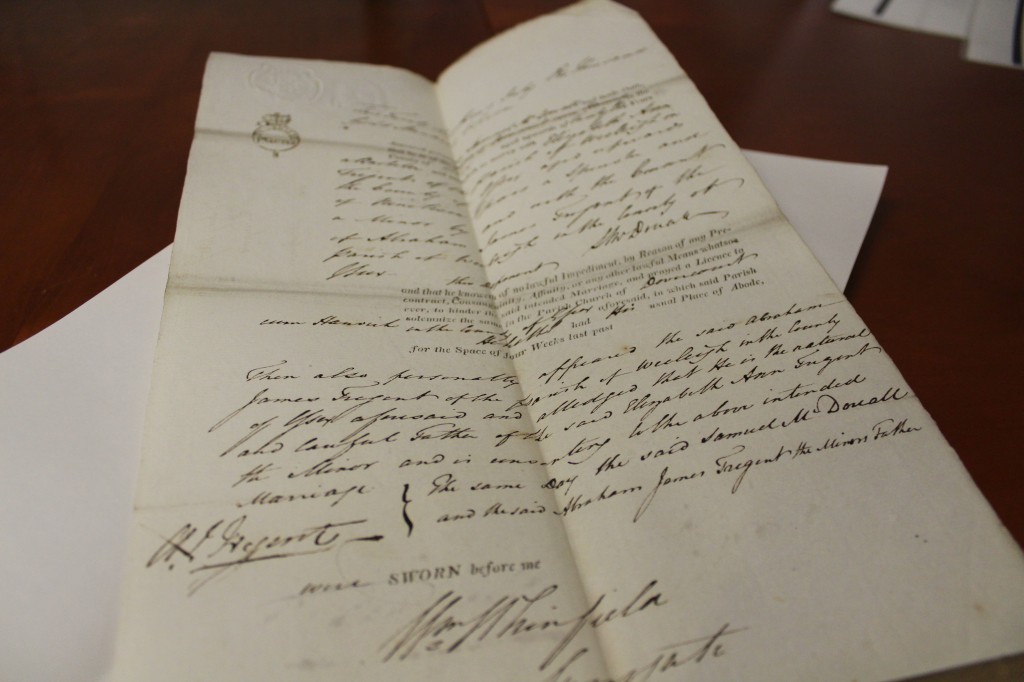

The marriage allegation of Captain Samuel McDouall and Elizabeth Ann Tregent. The allegation states that there is nothing to stop the couple legally marrying (D/ACL 1807/28)

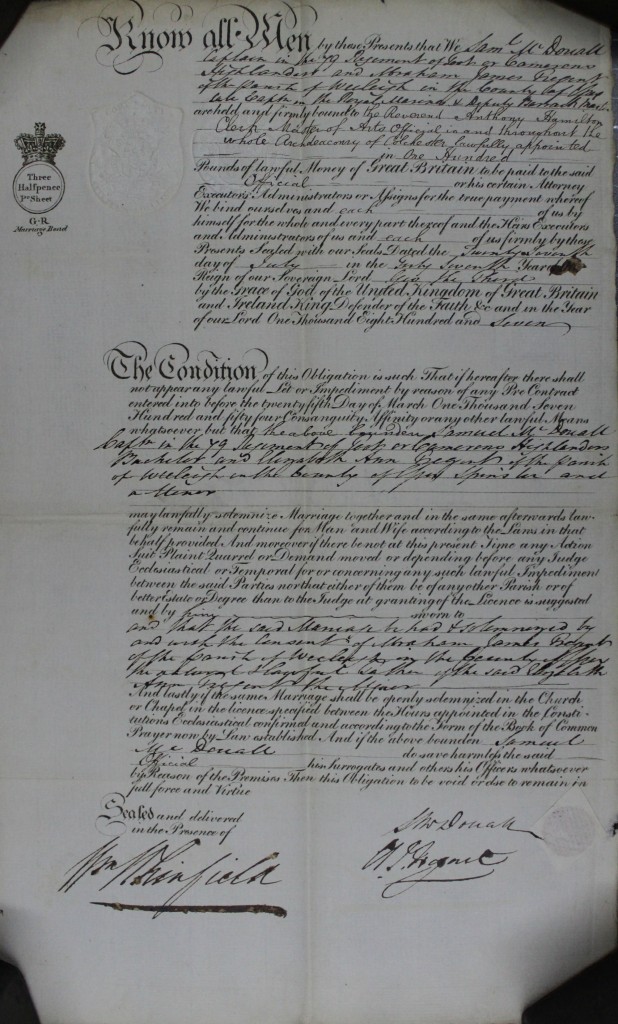

The bond which accompanies the allegation, pledging £100 if any just cause was later found which would prevent a later marriage. It is signed by Samuel McDouall and the bride’s father, Abraham James Tregent, and by William Whirfield, who was present at the couple’s wedding (D/ACL 1807/28)

The marriage took place at All Saints church in Dovercourt the very next day after the issue of the licence.

The 1807 date places the marriage in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars. McDouall’s profession is recorded as a Captain in the 79th Regiment of Foot, otherwise known as Cameron’s Highlanders. The first Battalion of the regiment was at this point stationed at Weeley, Elizabeth’s home parish. McDouall is said to be living at Dovercourt, probably the site of the officers’ billets. Elizabeth’s father was a military man himself – he is described as a Deputy Barrack Master, and a former Royal Marine.

The information in these records gives us several interesting avenues to pursue to find out more. The regiment’s military history tells us that McDouall served with the camerons during a turbulent period. His age is not given in their marriage record but he must have been some years older than her.

He was appointed as a lieutenant in 1795 before the regiment was posted to Martinique on garrison duty. The posting was to prove disastrous for them; fever swept through the 79th and only a skeleton of the regiment returned in Britain in 1797. The regiment was swiftly made up to strength and Captain McDouall would go on to serve in Holland in 1799, during which year he was made Captain, and in Egypt in 1801, where he was injured in fighting at Rhamanieh. He would later receive a Gold Medal from Sultan Selim III for his part in this action. One of the witnesses to McDouall’s marriage to Elizabeth was William Imlach, who was also a Captain in the 79th Regiment, and who received the same gold medal as Captain McDouall.

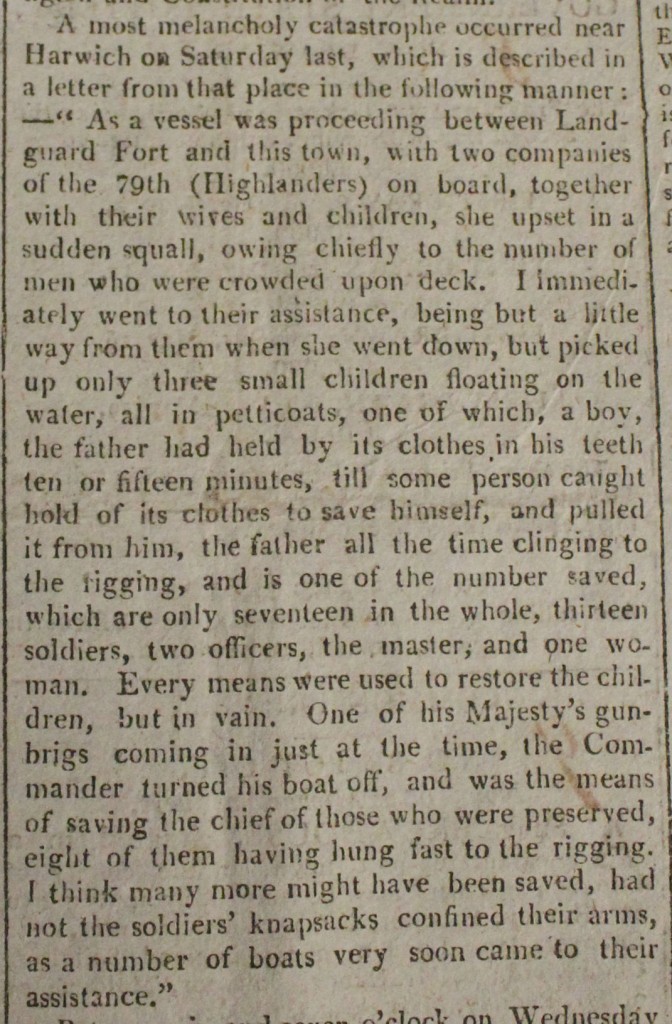

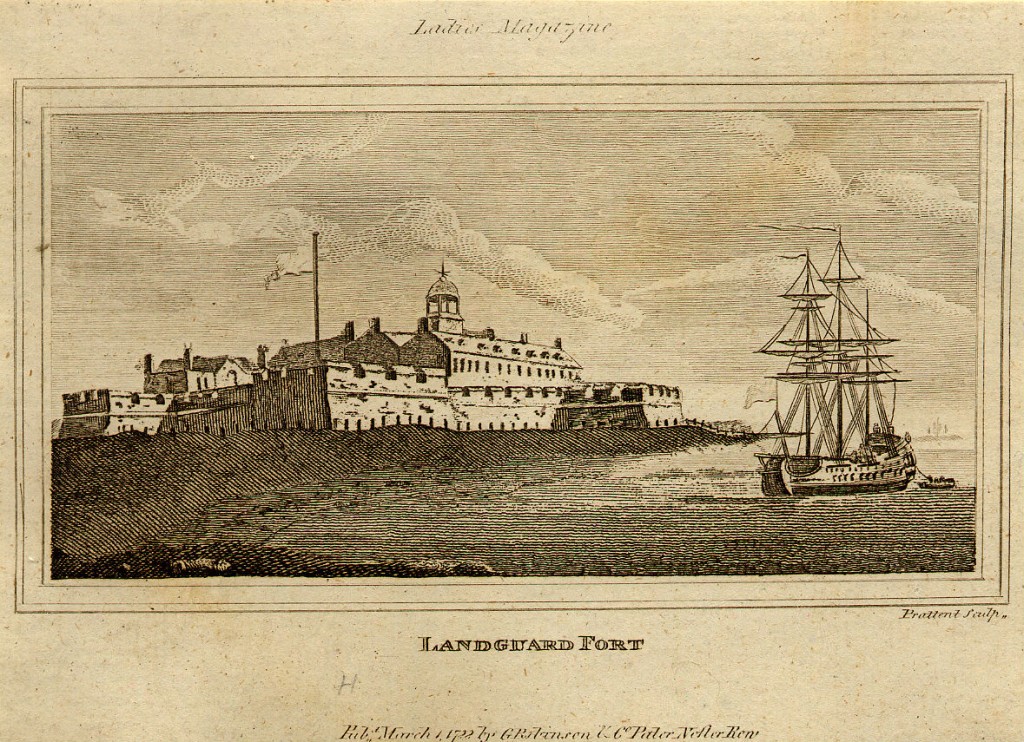

The regiment and Captain McDouall spent some considerable time stationed in Ireland on garrison duty before marching for London in 1806 to form part of the procession for Admiral Lord Nelson’s funeral. They were then posted to Colchester and then to Weeley where Captain McDouall would meet Elizabeth. Shortly before their marriage, in April 1807, tragedy struck the regiment when a boat carrying several men of the 79th from Landguard Fort in Felixstowe to Harwich sunk. More than 70 of their men were lost as several women and children, as described in the Chelmsford Chronicle:

Prattent Sculptor, published. March 1st 1788 by G. Robinson & Co Paternoster Row, extracted from Ladies Magazine (I/Mb 170/1/32)

At the end of July 1807 the regiment embarked for Denmark and be engaged in the Battle of Copenhagen during which the French were deprived of the valuable prize of the Danish fleet. The regiment would go on to be involved in the Peninsular War in Portugal and Spain, being part of Sir John Moore’s disastrous retreat to Corunna during which many of the regiment were struck down by fever both during the campaign and on their return to England in 1809. Many of the regiment who were left behind during the retreat went on to form part of a regiment of detachments which was engaged at the battle of Talavera at which the first of the French Eagles was captured. However, it is likely that Captain McDouall was part of the contingent which had returned to England, as he retired his commission in July 1809. He is believed to have died in 1812 in the West Indies.

What we do not know is what happened to Elizabeth. It is likely that as a wife of an officer she would have been able to travel to Europe with the regiment, but we do not know whether she did so.

There is a story behind every single one of our marriage licences – including stories that might be part of your family history. The licences are currently searchable on a paper index in the ERO Searchroom, and as we continue to add more names to Seax they will become even easier to find. What stories might they help you discover?