Ahead of The Fighting Essex Soldier: War Recruitment and Remembrance in the Fourteenth Century on 8 March 2014, we asked one of our speakers, Dr Jennifer Ward, to fill us in on some of the background of what Essex society looked like in the 1300s.

With the conference on The Fighting Essex Soldier: War Recruitment and Remembrance in the Fourteenth Century being held at the ERO on 8 March next year, we shall all learn a lot about warfare and the ways in which most Essex people were involved in the wars. 2014 marks a significant anniversary in the history of Scottish warfare, since it marks the defeat of the English at the battle of Bannockburn.

Much of the history of the fourteenth-century wars with Scotland and France can be reconstructed from documents and books in the ERO. Society was hierarchical, and leadership was undertaken by kings and nobles. The great Essex lords – the de Bohuns of Pleshey and Saffron Walden, the FitzWalters of Little Dunmow, and the Bourchiers of Stansted Hall in Halstead – were all involved. John Bourchier was unfortunate enough to be taken prisoner by the French in 1370, leaving his wife to raise his ransom and to take charge of his estates. William de Bohun, earl of Northampton, was one of the commanders at the battle of Crecy in 1346.

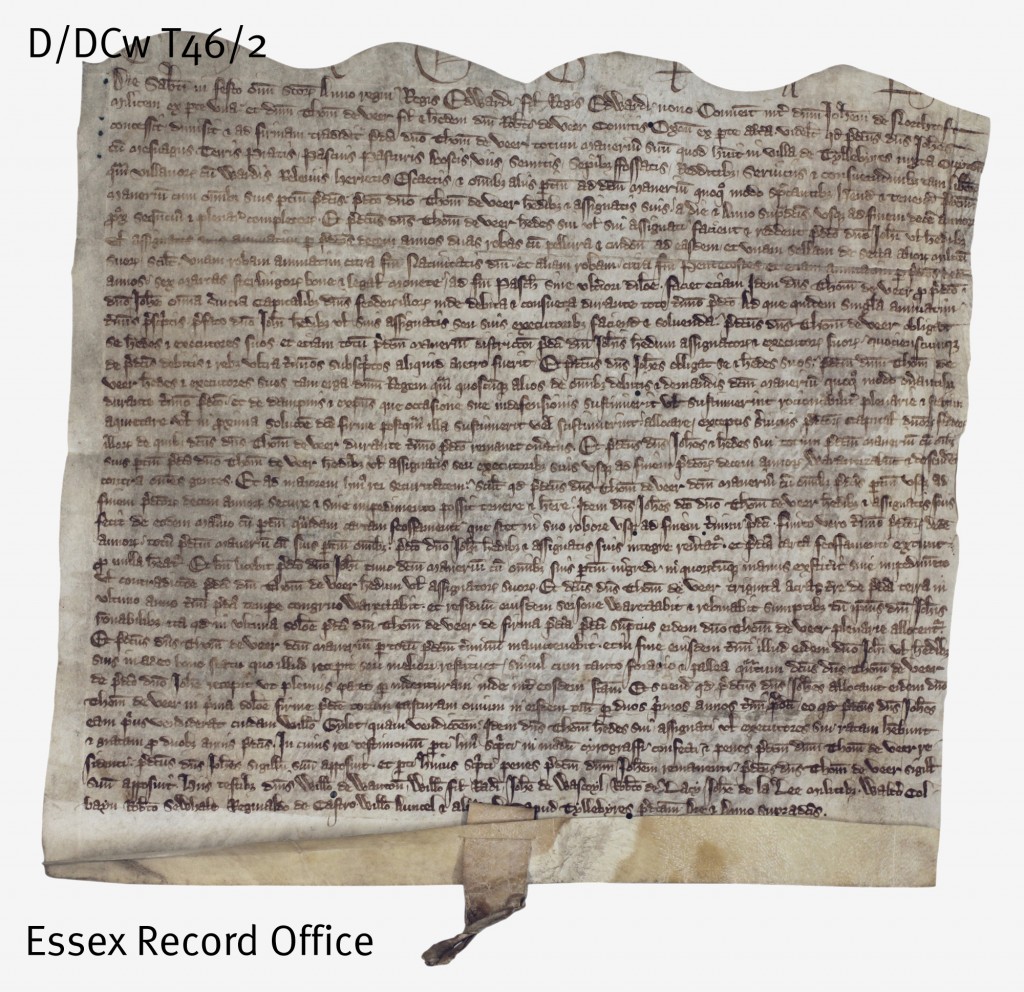

All lords had their retainers who wore their livery and received fees. In 1315, Sir John de Northtoft became the retainer of Sir Thomas de Vere (D/DCw T46/2). He was to receive two robes a year at Christmas and Pentecost, a saddle to match those of Thomas’s other knights, and a yearly fee of £4. The arrangement was to last ten years. Retainers were used for peacetime and/or wartime duties.

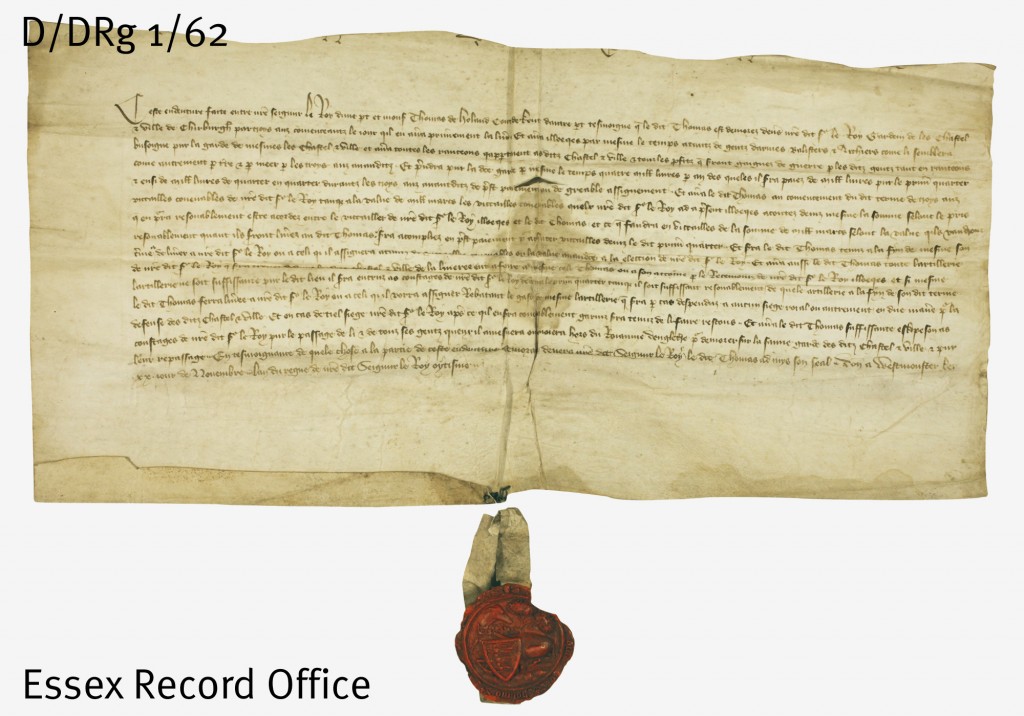

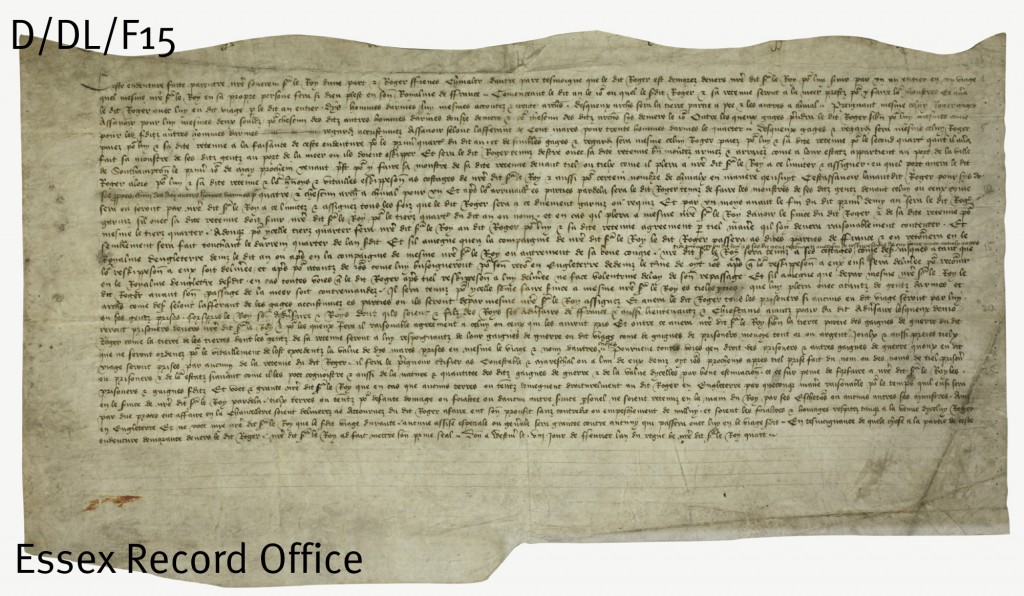

For the Hundred Years War, the Crown raised cavalry by drawing up indentures with military leaders, specifying how many men they were to bring, their pay, and the terms of their military service. An indenture of 1384 between Richard II and his half-brother, Sir Thomas Holland, earl of Kent, (D/DRg 1/62) laid down the details of Thomas’s governorship of Cherbourg. He was to have as large a fighting force as he thought necessary, was to have all ransoms and profits of war, and he was to be paid £4,000 a year by the king. A later indenture of 1417 between Henry V and Sir Roger Fiennes (D/DL F15) provided for Roger to serve the king for a year with ten men-at-arms. Again, pay and conditions of service were laid down.

Infantry, including archers, were recruited by commissioners of array in each county. Many Welsh contingents of archers served in the wars. Merchant ships were used for transport, and were confined to the ports if a campaign was being planned.

During the fourteenth century, the gentry of the county became increasingly prominent in local administration and justice, as well as serving in the wars themselves. Sometimes they fought as young men, and took on administrative tasks as they grew older. They served as commissioners of array, as keepers of the peace, and from the mid-fourteenth century as justices of labourers and justices of the peace. It was essential for the king’s peace to be kept in the county while the king was campaigning abroad.

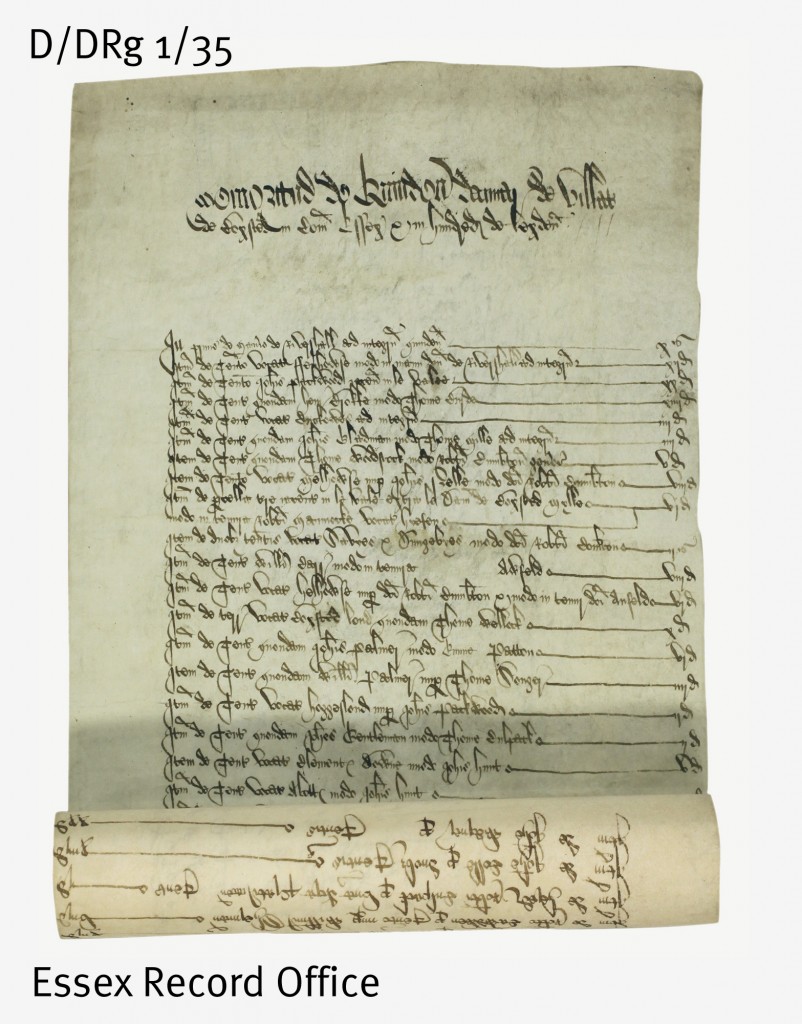

Moreover, much money was needed for the prosecution of the war. England, unlike many other European countries, had a national system of taxation, with each levy of taxes having to be agreed to by parliament. Parliament, comprising the king, the nobility, and the commons made up of two knights from each county and two burgesses from each town, grew rapidly in importance from the reign of Edward I onwards. The taxes were originally levied on people’s movable goods, but from 1334 each village or town had to pay a fixed sum. The assessment for Boxted survives (D/DRg 1/35), and here the 1334 tax was levied on landholdings, both small and large.

Most Essex people were affected in some way with the wars, and the 1340s and 1350s brought great victories at Crecy and Poitiers. However, in 1348-9, the Black Death reduced the English population by at least 0ne-third, and the court rolls for Essex show that many villages and towns suffered severely, such as Blackmore and Margaretting (D/DK M108, D/DP M717). There are signs in the court rolls of increasing peasant restiveness after the Black Death. This culminated in the Great Revolt of 1381, sparked off by refusal to pay the third poll tax. Men of Essex were no longer willing to pay taxes and put up with serfdom in an era of population decline and military defeat.

Find out more at The Fighting Essex Soldier: War Recruitment and Remembrance in the Fourteenth Century on Saturday 8 March 2014. More details here. Dr Ward has curated a display of documents to accompany the conference which will be in the Searchroom from January-March.