We are lucky to have a team of amazing Essex Sound and Video Archive volunteers, who give their time and expertise to help make the recordings more accessible. In this blog post, Lilly highlights some of her favourite clips from Ted Haley’s collection of recordings (ERO reference SA 20). You can read transcripts for all the clips in this blog post here.

Between the mid 1960s and the late 1980s, Edward ‘Ted’ Haley conducted a series of audio recordings and interviews in the south Essex area, focusing on Basildon and Southend-on-Sea. Over the course of the interviews, Ted met a variety of people with an even bigger variety of experiences and stories to tell, with folks such as Harold Whitely – also known as Rainbow the clown – and talented silent film organist Ena Barga, to name but a few. All these recordings, preserved at the Essex Record Office, give a unique perspective of late twentieth century Essex and unlock a door into the past of the town centres and high streets that we now walk around decades later.

Postcard showing boats at Marine Parade Beach, Southend, c.1955 (I/Mb 321/1/57)

The Second World War

The interviews Ted conducted in the Basildon area include many interesting anecdotes from those who experienced the Second World War, though the perspectives of the interviewees vary entirely from ex-soldiers and RAF veterans all the way to a member of the Norwegian Resistance.

In 1980, Ted interviewed a man named Alan Mitchell who was a volunteer during the war on the Royal Navy’s submarines. He describes his experiences during the war, including the medical examinations they experienced upon arrival at Gosport, Hampshire.

In this clip, Alan discusses the claustrophobia test they were put through (SA 20/1126/1)

He also interviewed another veteran, Robert Ramsey, who served with the RAF (SA 20/1140/1). In the interview, Robert tells the story of when he was shot down by a night fighter over Louvain on the night of 10 May 1944. He details how he ran to a French farmhouse and was given food, water and radio access by a peasant family who risked their lives aiding him and hiding him in a haybale on their farm.

Ted also interviewed Mike Karslake, who recalled his experiences of being a child during the Blitz in Acton, London. He begins with a story of how he was evacuated, with the help of his father’s quick talking, to his Nan’s house in North Devon. However, after a year, he returned home and experienced the Blitz with his mum and grandfather. Mike also recounts his schooldays during the war and how air raid sirens would even occur in school hours.

Mike describes how his grandfather handled the air raid warnings and how he was eating during an air raid warning in school (SA 20/1131/1)

In 1981, Ted interviewed a Norwegian woman, Borghild Mitchell (nee Gulbransen), pictured below. She describes her experiences during the war, watching her country being taken over by German artillery and the changes that meant for Norwegian society – for example, the curfews that citizens had to follow and the passes they had to carry when walking through the streets after the curfew. She also describes being part of the Norwegian Resistance and how this led to her being interrogated and her fiancé being killed by German soldiers. When Ted asks her about the interrogations, and she answers with a story filled with pain, yet a sense of loyalty and determination to stay true to the resistance is heard throughout her recount.

Borghild describes being interrogated and feigning a lack of understanding to give her more time (SA 20/1141/1)

Photograph of Borghild Mitchell aged 18, taken in 1942 (SA 20/1141/4)

Events in South Essex

As well as interviews with people living in south Essex, Ted also recorded important moments and events. On 10 September 1981, Essex Radio aired its first ever radio broadcast. Over the opening weekend, team members were introduced and in person interviews took place across Essex, including with the American singer and bassist, Suzi Quatro. Listening to this recording is very interesting as not only are you hearing how excited people were for Essex Radio to air, but you also get a snippet of adverts that were popular at the time – in some ways, even more telling about the time period than the interviews with 1980s Essex folk are.

An advert for Laylor’s car dealership in Brentwood and for Banks American Restaurant in Westcliff-on-Sea (SA 20/1127/1)

In 1985, Ted recorded a concert at Rochford Hospital. As part of the recording he interviewed Ena Barga, a musician who specialised in the organ and played for silent films throughout her career.

Ena discusses her dislike for modern music, followed by a recording of her playing the organ at the concert (SA 20/1148/1)

‘Royal’ date, a newspaper clipping showing Ena Barga and her sister Florence De’jong on the renovated Compton theatre organ at the State cinema at Grays (SA 20/1148/4)

The novelties of Southend-on-Sea

Some of Ted’s interviews in Southend and the surrounding areas, including Westcliff and Leigh, touched upon some of the novelties of these seaside towns, such as Rossi’s ice cream, rock candy and the fishing industry. The interviews he conducted delve into the fascinating history surrounding these seaside stereotypes.

His interview with George ‘Pie’ Osborne and Cecil Osborne covers the history of cockling that was a main source of income for many Southend folk in the early 1900s. Whilst the history of cockling, fishing and shrimping are key parts of this interview, a notable part of the interview is the accents of the two men, which they describe to be ‘local accents’. The dialect that they use in addition to this is compelling with one of which being the word ‘sawney’ being slang for the word simple.

George and Cecil talk to Ted about their accents – listen to how they pronounce words like ‘coat’ and ‘rope’ (SA 20/1557/1)

Photograph of Cecil Osborne, undated (SA 20/1557/4)

A sweet treat that many love about seaside towns such as Southend is a hard stick of rock. In one interview Ted talks to Mr. S Knatchbull who owned Grosvenor Confectionery and worked making handmade regular and lettered rock in 1979 (SA 20/1566/1). He discusses the rock making process, listing the ingredients and flavourings he used when ensuring a variety of tasty sticks of rock. He also talks about the largest piece of rock he ever made being 6 foot 6 inches in length and 6 inches in diameter. The humungous stick of peppermint rock travelled all the way into London, by train, to a charity fundraiser event in the 1950s.

In 1983, Ted interviewed Ugo Rossi, whose father – Augustino ‘Gus’ Rossi – partnered with Peter Rossi to establish the famous frozen treat throughout the Southend high street and waterfront. They talk about this partnership dissolving and how the waterfront shops were owned by Peter and the high street shops were owned by Gus. What’s most surprising about the interview is the price a Rossi’s ice cream used to be … 1 penny for a regular cone and 2 pence for a larger cone!

Ugo talks about his father’s desire for a Rossi’s ice cream to not be too sickly a treat (SA 20/1540/1)

Interesting folk

Ted’s interviews show how each person has fascinating stories waiting to be told. One interview with Harold Whitely – also known as ‘Rainbow the Clown’ – particularly stands out. Speaking in 1981, Mr Whiteley talks about starting his career as a clown aged six, and his joy in performing as a youth and love for the intricate face paints and costumes of the clowns he saw growing up in a travelling circus. He also talks about the history of his family and circuses. His grandmother, Lorrina, worked in America in the circus under Barnum and Bailey’s circuses in America, a name most recognised from one of the owners P. T. Barnum. Furthermore, his grandfather’s circus performed for Edward, the Duke of Edinburgh (Queen Victoria’s son).

Harold describes his pleasure in being a performer as a child and also how he performed in front of smaller audiences as a clown (SA 20/1123/1)

An interview previously mentioned, with Alan Mitchell, was not only compelling due to its discussions on Navy training during the Second World War, but also due to the fact that Alan was a hairdresser before and after the war, making him knowledgeable on male hair trends of the mid to late 1900s. He and Ted discuss the era of the Beatles leading to a trend of long hair for boys and also the up-and-coming punk style of hair and fashion. Hearing their detached discussion in the punk style is particularly funny due to their lack of awareness of the style.

Ted and Alan discuss fashionable hairstyles for men and their opinions of the punk style (SA 20/1126/1)

Overall, the Ted Haley recordings are incredibly fascinating and a worthwhile listen. They delve into the people of the period and allow us to now look back onto that period with nostalgia or discovery, keeping that part of south Essex history in an audible time capsule, ready for your listening.

You can browse the full catalogue of Ted Haley’s recordings on Essex Archives Online and listen to them in our Playback Room in Chelmsford. You don’t need to make an appointment – all you need is an Archives Card. Find out more information about visiting us on our website. You can also find some of Ted’s recordings on Essex Sounds, our map of sounds from across the county:

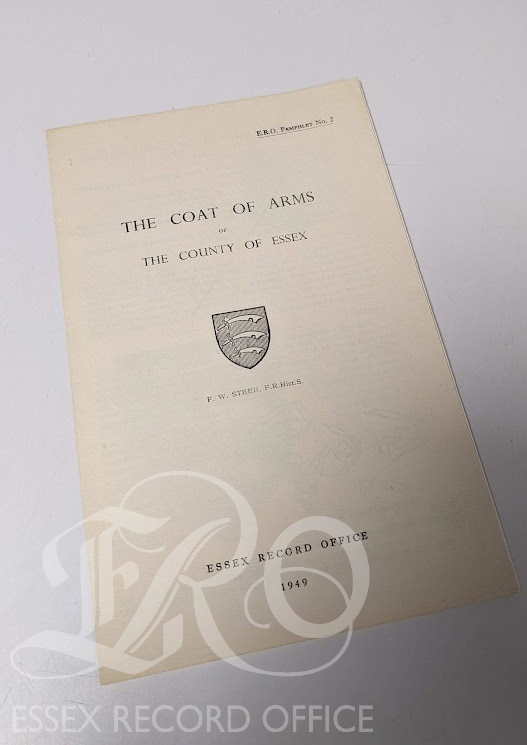

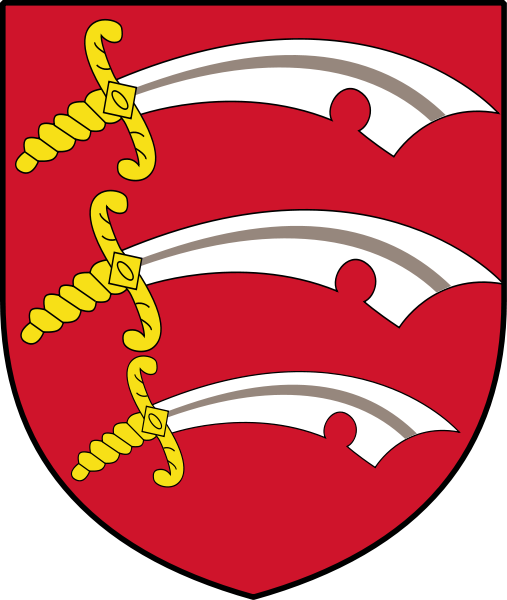

Gules, three Seaxes fessewise in pale Argent,

Gules, three Seaxes fessewise in pale Argent,