Ahead of Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July, we begin a manorial mini-series exploring what these fascinating documents can tell us about Essex in the past. In this first post Archivist Katharine Schofield writes for us about what a manor actually was…

A manor was essentially a unit of land. Manors were at the heart of the post-Norman Conquest feudal system whereby all land was owned by the King. He rewarded his followers (or tenants-in-chief) by giving them land which they held in return for military service to the King. They in turn rewarded their followers (or tenants) on the same basis. At the bottom of the structure was the knight’s fee, the amount of land considered sufficient to finance the service of one knight. Domesday Book, produced in 1086, shows the beginnings of this system and is arranged by manors rather than towns or villages. It is for this reason that a number of places appear in it more than once.

Manors and parishes rarely coincided. Domesday Book, for example, records three manors in the parish of Takeley, owned by Eudo Dapifer [the steward], Robert Gernon and the Priory of St. Valéry in Picardy. By the time that the Revd. Philip Morant wrote The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex in 1768 there were four manors in the parish – Waltham Hall, Colchester Hall, St. Valerys or Warish Hall and Bassingborns which could trace their ownership back to the three Domesday manors. Manors could also have land in a number of different parishes; for example, records of the manor of Berechurch or West Donyland in Colchester included property in Old Heath and on East Hill and St. John’s Green, all in other parishes.

The lord of the manor owned everything in and of the manor – the crops, animals, mineral, hunting and fishing rights and also the tenants, who could be bought and sold and who owed days of labour and items of produce to the lord. The lord would either keep the land and farm it using the labour of his tenants or he would rent the land, retaining jurisdiction over it.

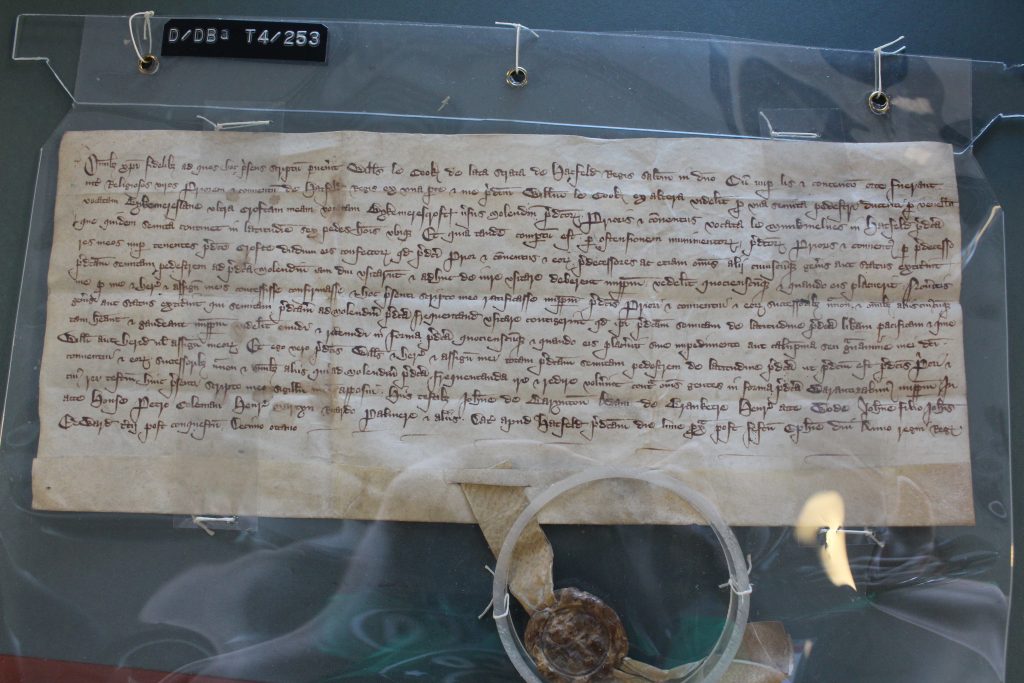

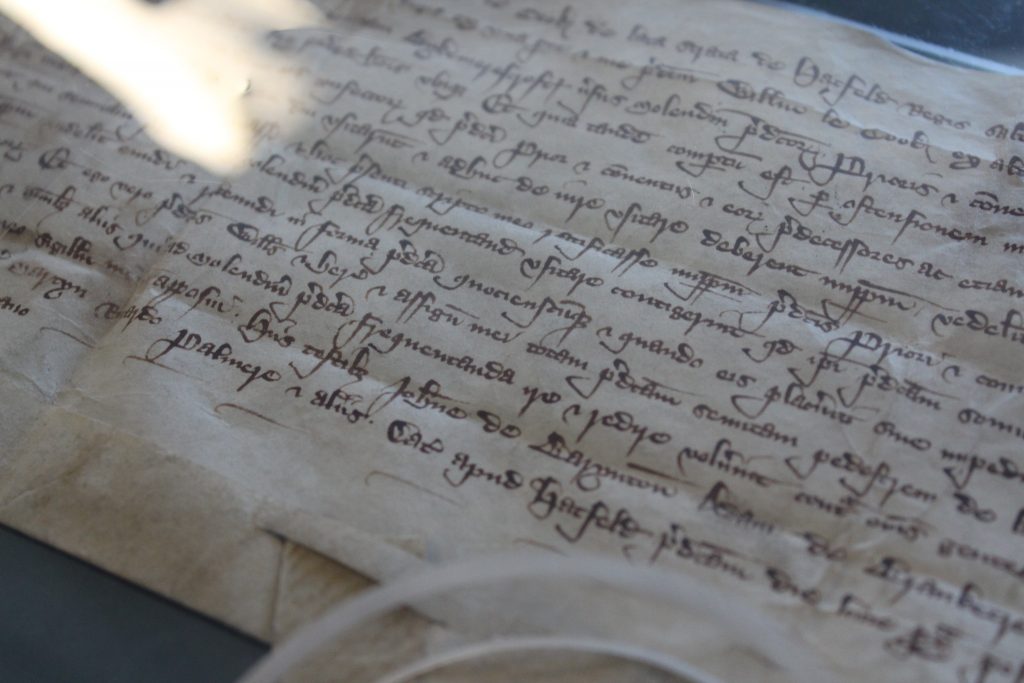

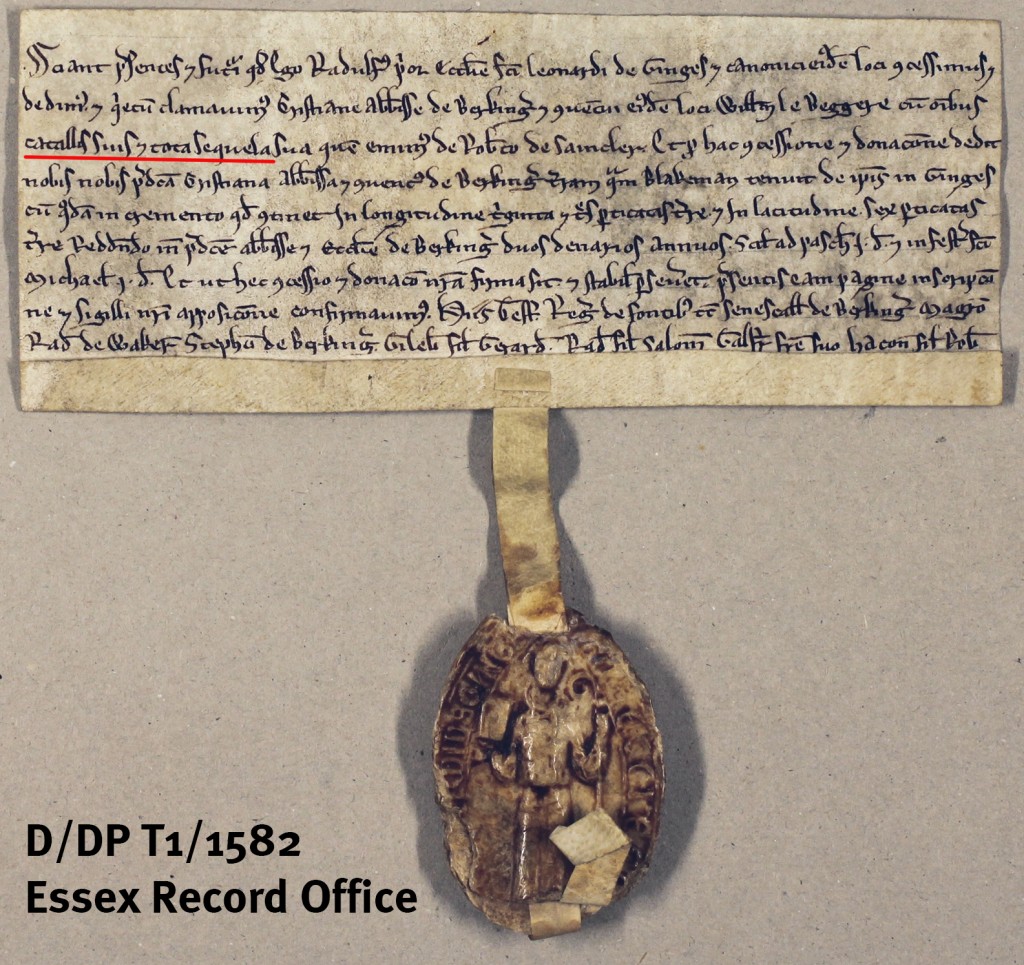

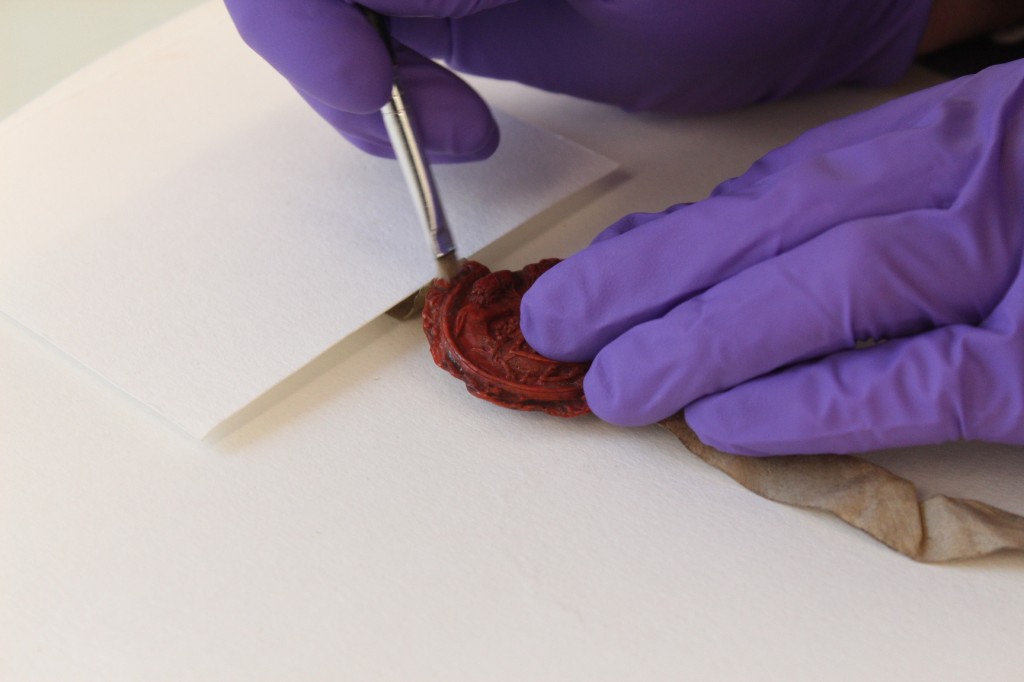

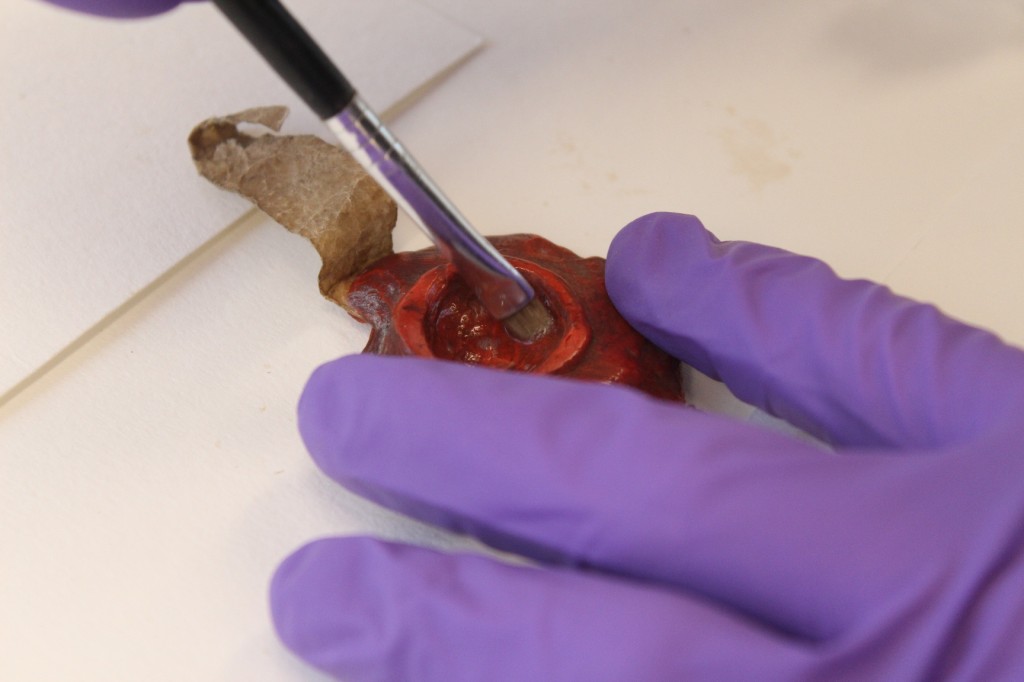

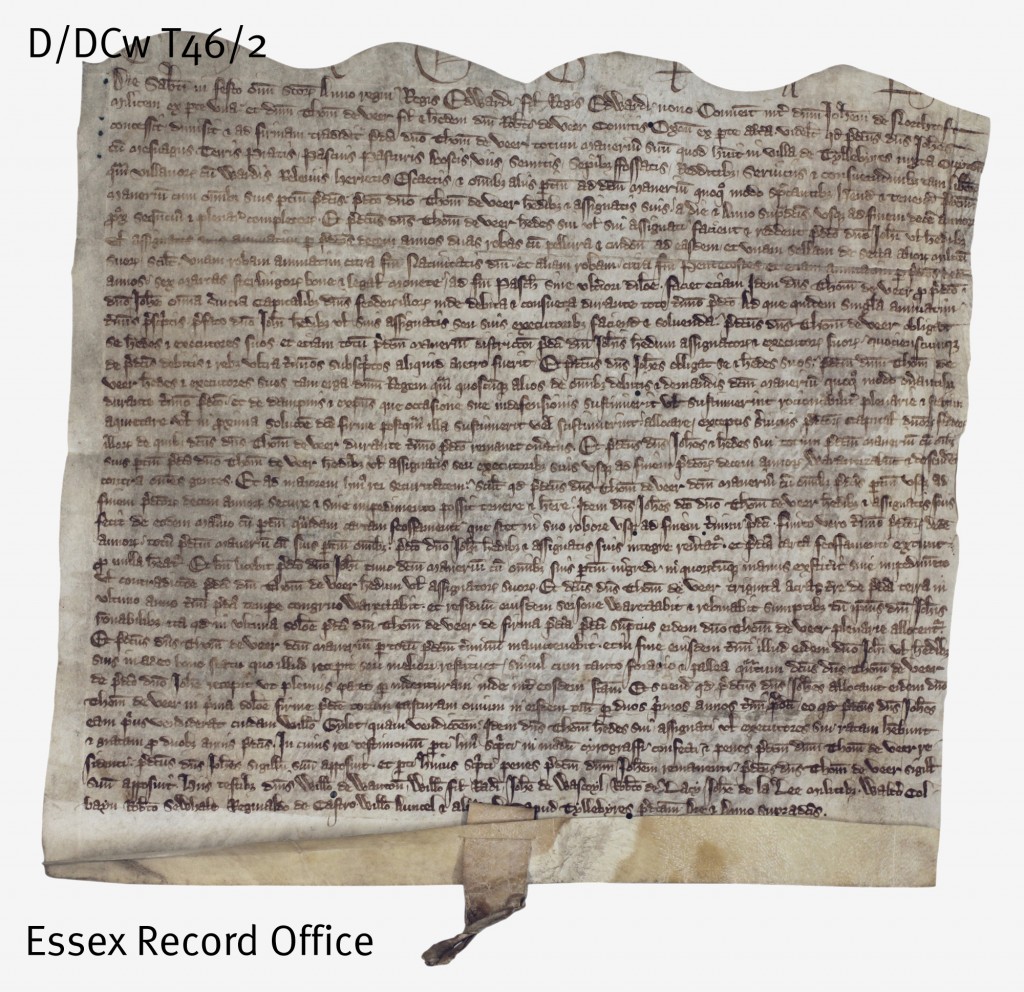

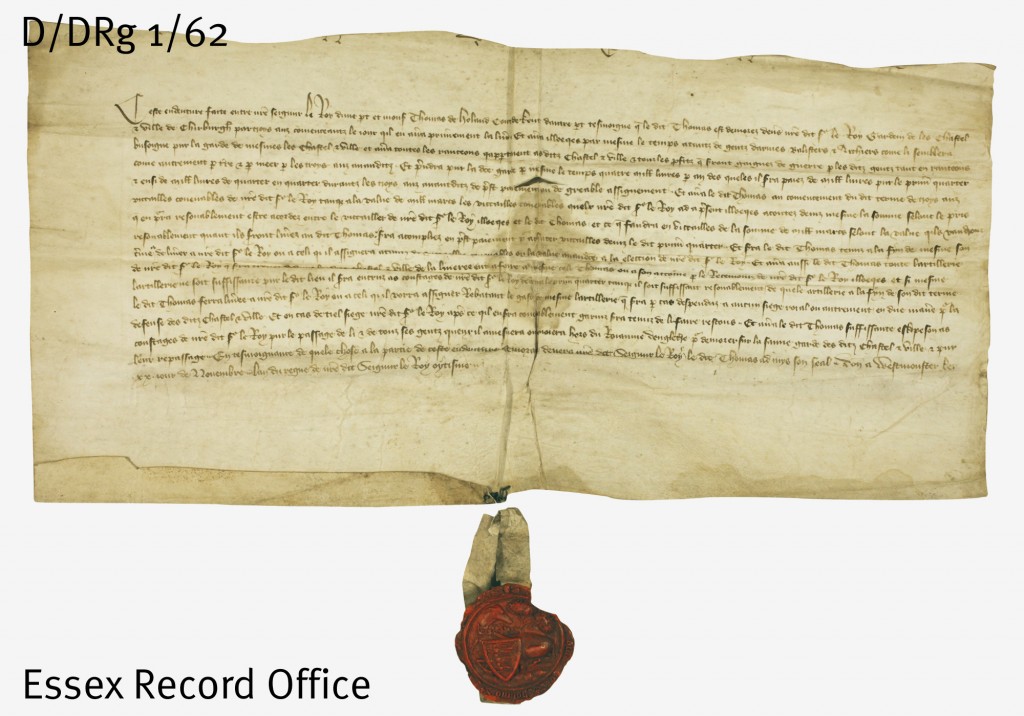

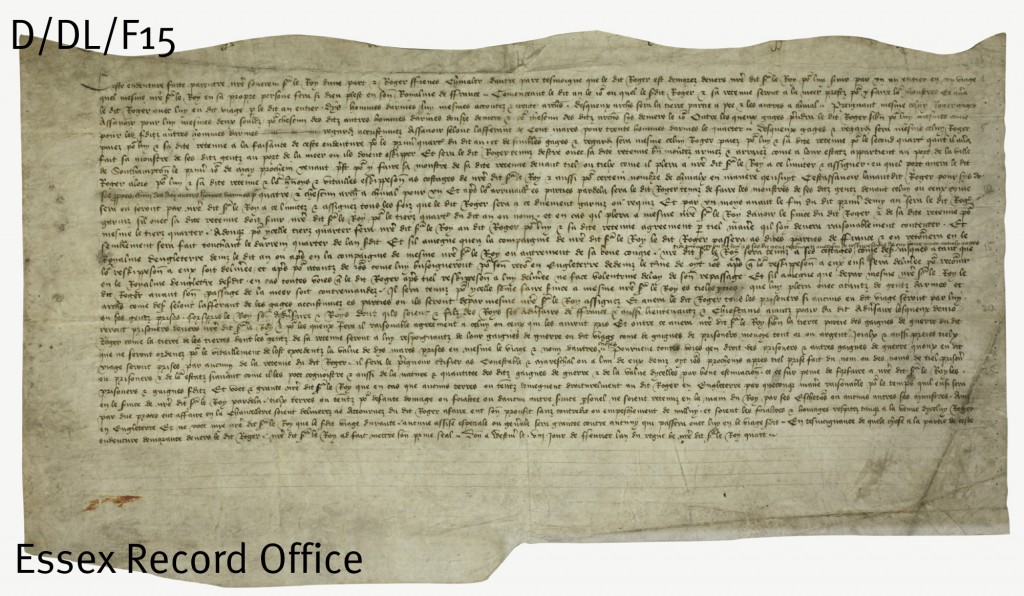

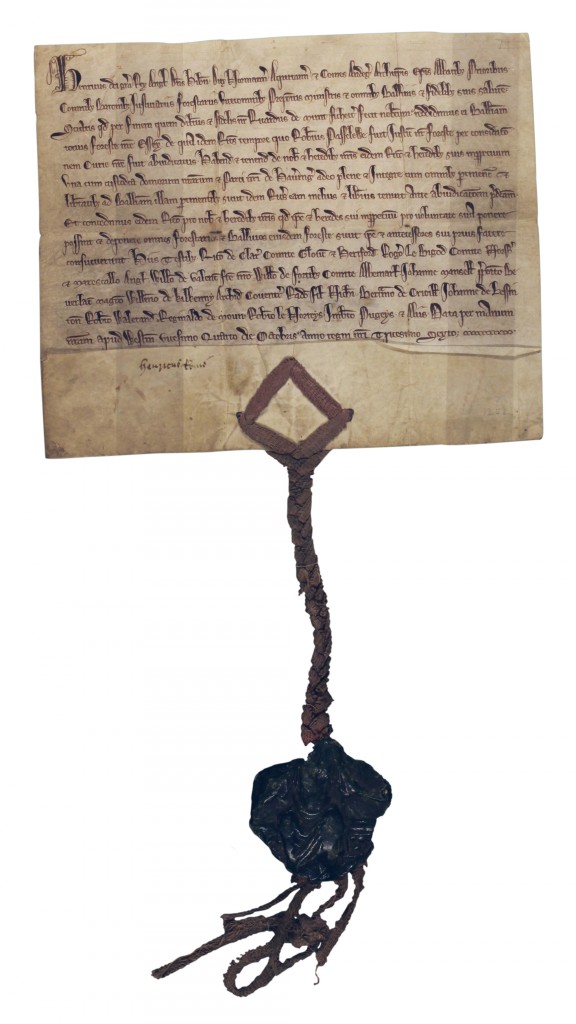

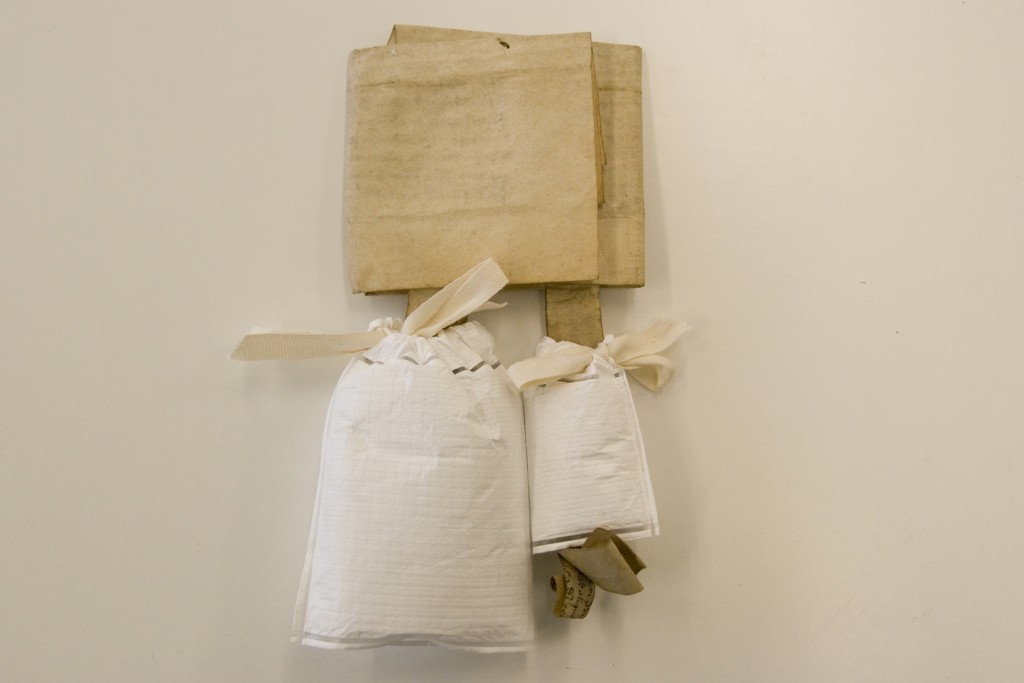

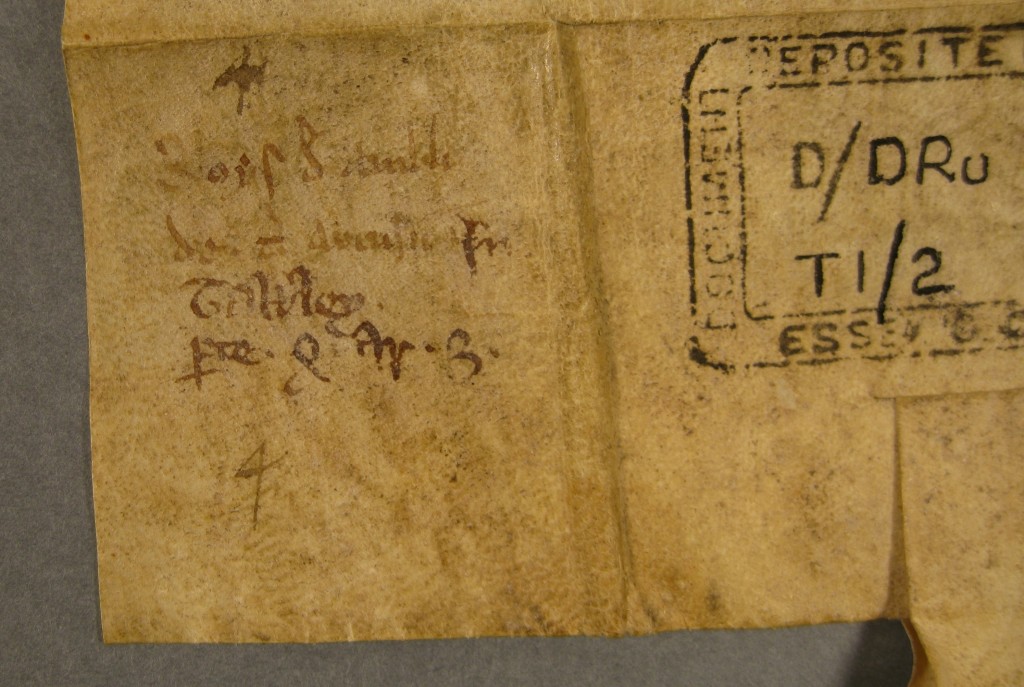

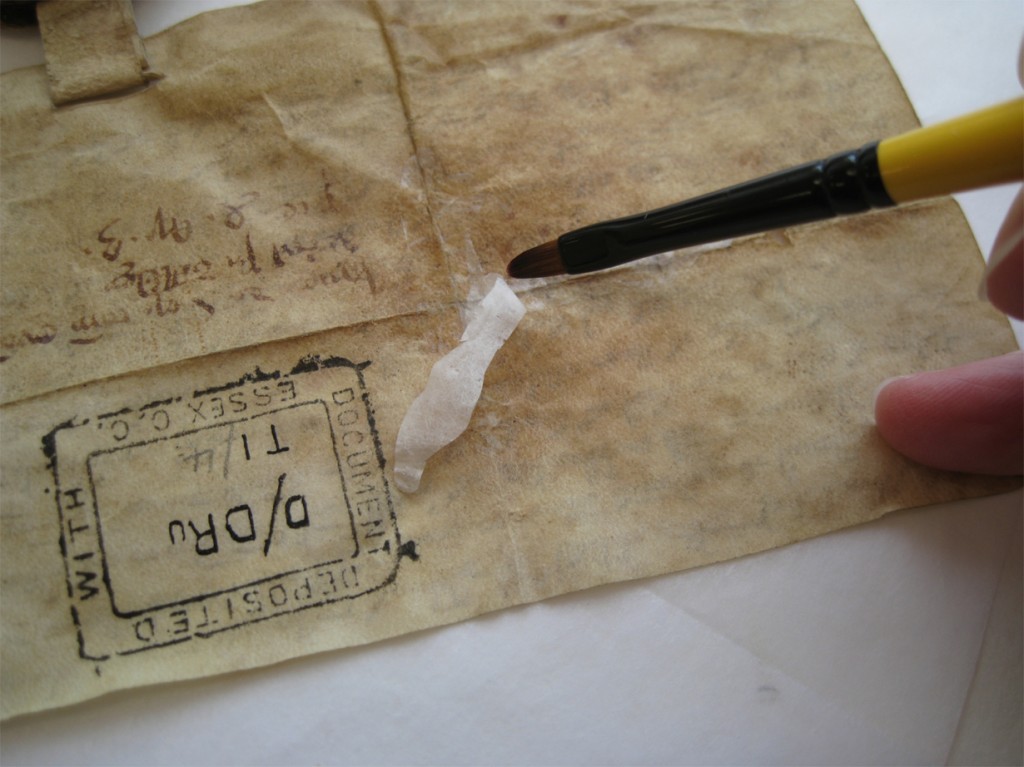

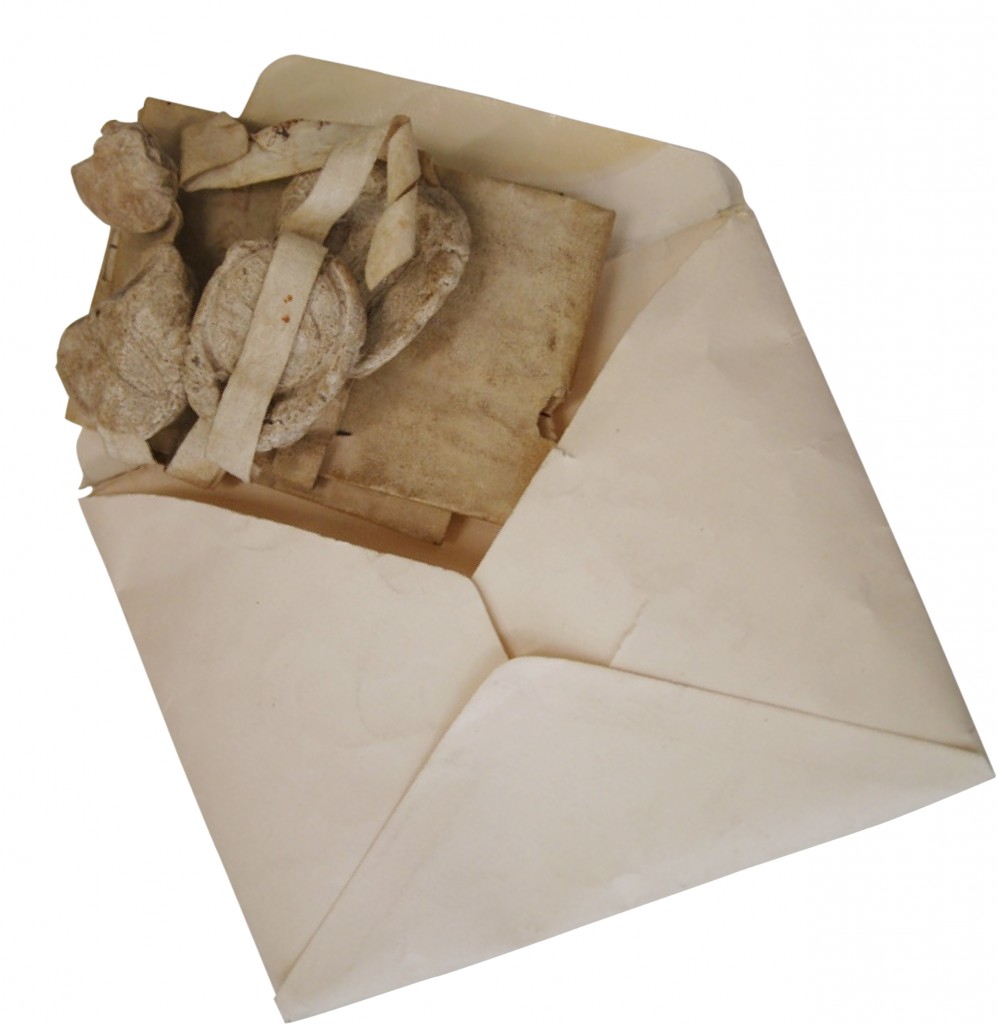

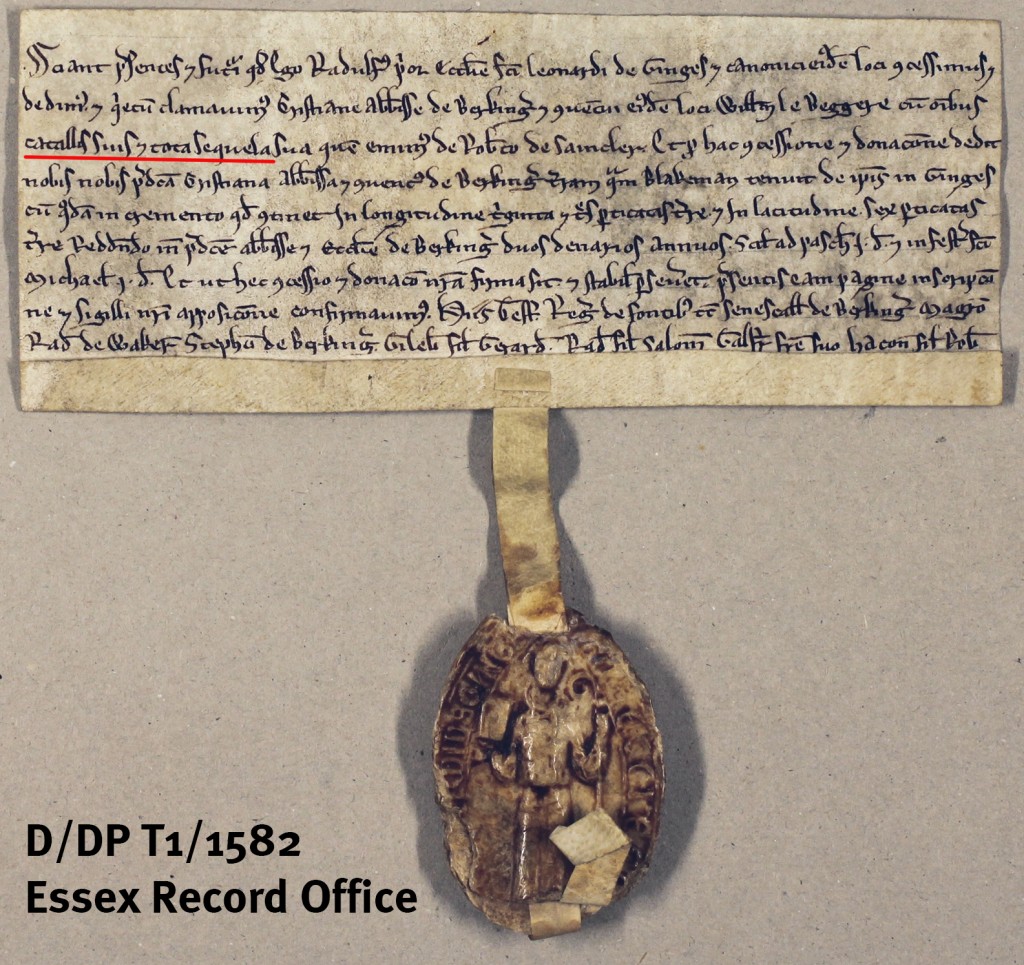

Among the earliest deeds in the Essex Record Office are a small number of early 13th century grants where named individuals, with their belongings and descendants, or chattels and issue [catallis et sequela – underlined in red below]), are sold or exchanged for land.

Grant by Thoby Priory of William le Beggere to Barking Abbey, c.1202-1201 (D/DP T1/1582). William had originally been purchased by the Priory from Robert de Saincler. In return for this grant, the abbey gave the priory land in Mountnessing.

As tenants were considered part of the property, the lord was also entitled to customary dues which would be paid as compensation for the loss of income that the tenant or members of his family would bring. These included payments which were required when a son was sent to school or entered holy orders, as well as ‘merchet’ which was paid when a daughter married and ‘chevage’ paid to live the outside the manor.

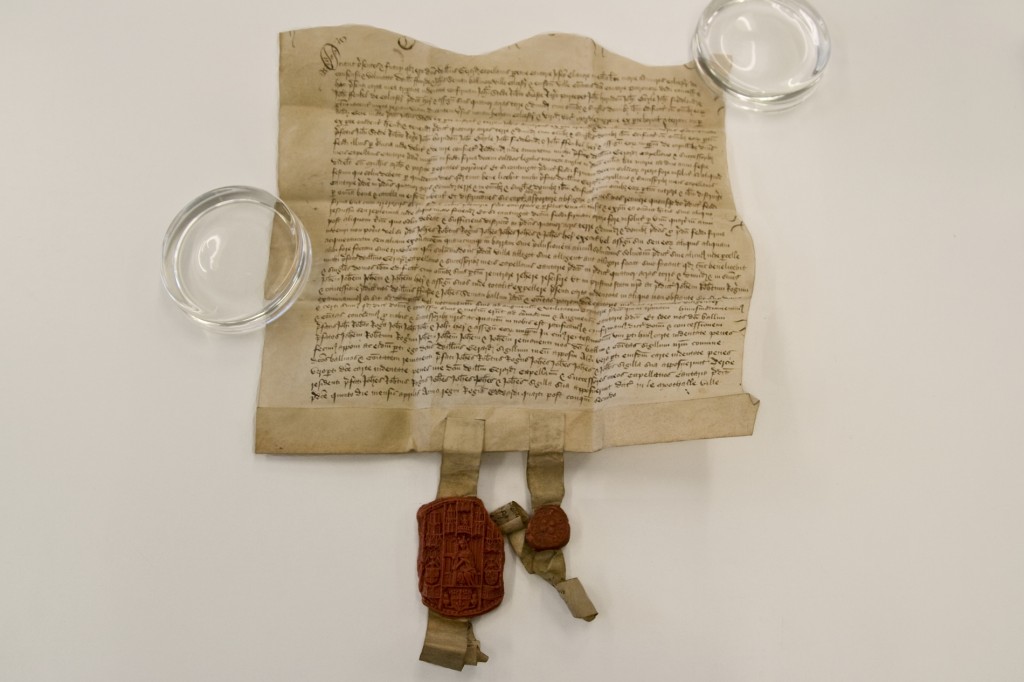

The territorial rights of the lord over the tenants and their lands were enforced in the manorial court – the court baron. Some, but not all, manorial lords also had jurisdiction over minor criminal matters in the court leet.

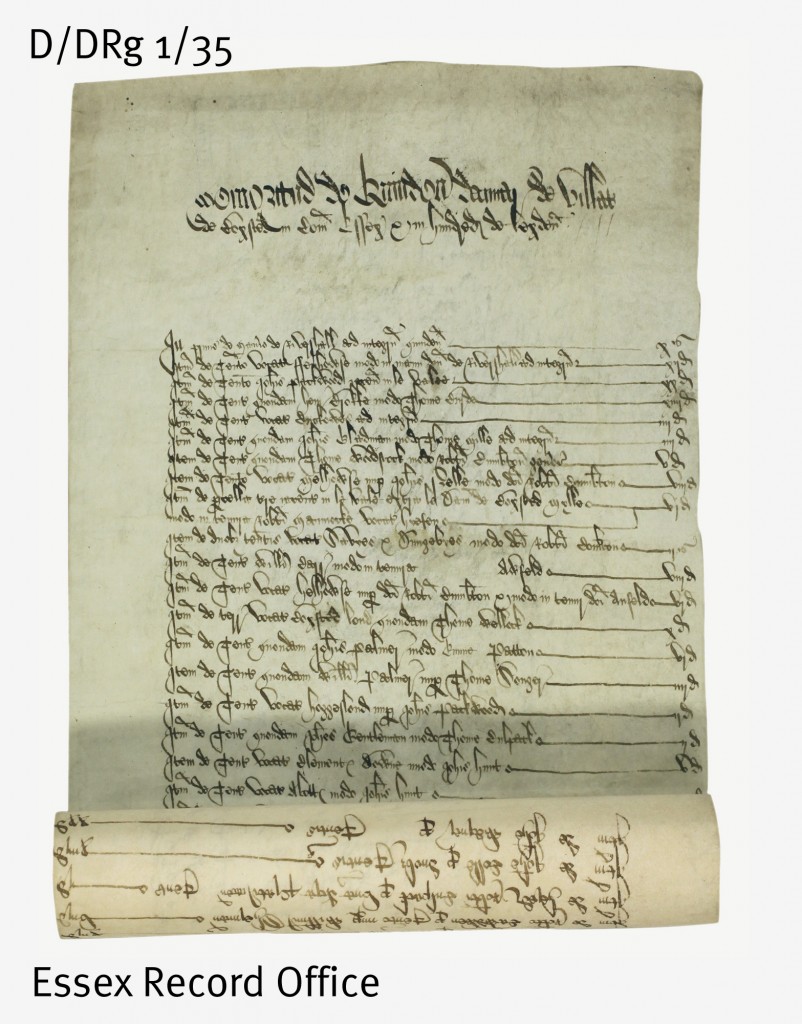

The rights of manorial lords did not change significantly over the centuries, but the nature of the manor did. Some rights ceased to be exercised and others became more important. It is estimated that the Black Death of 1348-1349 killed around a third of the national population and possibly as much as half of the population of East Anglia. This ultimately led to lords being unable to find tenants willing to work the land as they had done previously, and the labour dues of tenants being commuted to rents or quit rents. This, in turn, meant that records which commonly appeared in the early Middle Ages disappeared to be replaced with rentals. Similarly by the 18th century the business of the manorial courts was mostly taken up with the admission and surrender of land by copyhold tenants.

Manorial survey of Castle Hedingham by Israel Amyce, 1592. This survey book includes written descriptions of pieces of land illustrated with maps. (D/DMh M1)

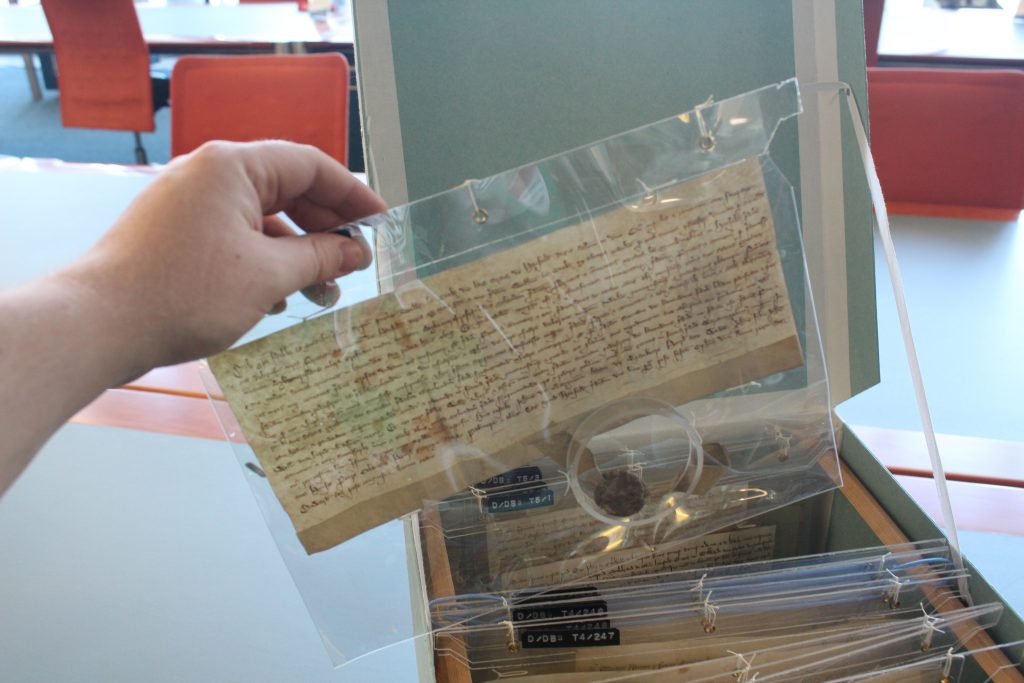

The Manorial Documents Register (MDR) was established in 1926, the year after manorial landholding (copyhold) was abolished, to record the location of documents and ensure that they could be traced if they were required for legal purposes. The two main types of manorial records listed by the MDR are:

- Court records – court rolls, later books, estreat and suit rolls, stewards’ papers, admissions and surrenders

- Assessment of land and financial records – surveys, extents, custumals, accounts (or compoti), rentals, and quit rents

As well as the records listed by the MDR, the Essex Record Office holds many deeds of copyhold properties and of the manors themselves. Manorial titles remain and still retain some rights, including the extraction of minerals and fishing and any remaining rights must have been registered with the Land Registry before October 2013 if a lord intends to continue enforcing them.

Over the last few years, the ERO has been contributing to a major update to the Manorial Documents Register, improving the catalogue and getting information online to make these useful and fascinating documents more available to researchers. Even if you don’t want to attempt reading the earlier Latin documents, from 1733 they were kept in English, so there may well be information contained within them of interest to your research in family history, house history, or local history. Essex through the ages on 12 July marks the completion of our contribution to the project, and celebrates the improved accessibility of these records for researchers.

Whether you are interested in using manorial records in your own research, or just want to enjoy hearing experts talk about them, join us for Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July 2014 to find out how you can discover centuries of Essex life using these fascinating documents. There are more details, including how to book, here.