Julie Miller, a masters student from University of Essex, has taken up a research placement at the Essex Record Office, conducting an exploration into the story of John Farmer and his adventures, particularly in pre-revolutionary America, and has been jointly funded by the Friends of Historic Essex and University of Essex. Julie will be publishing a series of updates from the 12-week project.

In part 7 of this series, we reach the end of John Farmer’s travels.

Just over a year after he came home from his epic American journey in 1715 John Farmer travelled back to America as he had planned.

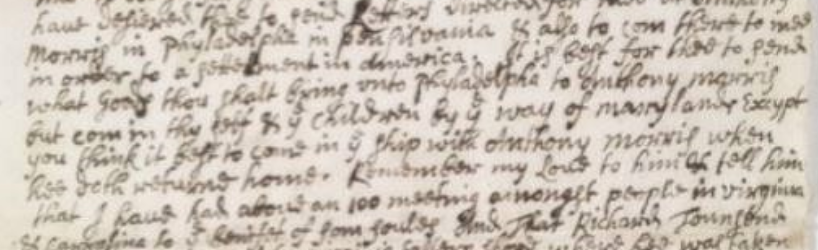

In a letter held in the journal collection at the Essex Record Office, dated Virginia 1st June 1716, he wrote to his wife Mary asking her to pack up her goods and join him in Philadelphia where they would settle permanently. He instructed her:

‘It is best for thee to send what goods thou shalt bring into Phyladelphia to Anthony Morris but com in thy self and ye children by ye way of Maryland excypt you think it best to come in ye ship with Anthony Morris when he doth return home.’[i]

However for some reason that didn’t happen. Mary stayed in Saffron Walden, possibly still nursing her sick daughter Mary Fulbigg or perhaps she had heard that John Farmer was already sowing the seeds of personal disaster and Mary decided not to put her self and her children at odds with the wider Quaker community. For what ever reason, Mary decided not to go to America to join her husband of 17 years and as a result she never saw him again.

John Farmer had arrived back in America as the first abolitionist arguments were at their height amongst Quakers. He had not passed comment in his journal of 1711-14 but must have witnessed the suffering of slaves in the Caribbean and on the plantations of Virginia and Maryland. Quakers had been troubled by the slave question a few times previously[ii] but had chosen to wait for a common agreement to be felt in the Yearly and Monthly meetings, almost certainly because the senior Quaker leaders were often slave owners with significant vested interests. The dichotomy was that Quakers believed all men were equal under God, and slave owning certainly didn’t sit well with their philosophy, but they were not yet ready to make any radical changes.

By early 1717 John Farmer had started an antagonistic anti-slavery campaign. It’s not clear what exactly triggered his impassioned fight, but it may possibly have been as a result of reading or hearing the testimony of seasoned abolitionist campaigner and fellow Quaker William Southeby. Southeby had been campaigning since 1696, and in 1714 had taken the Philadelphia Meeting to task saying, “it was incumbent on them ‘as leaders of American Quakerism, to take a high moral position on slavery”.[iii] He insisted Philadelphia did their Christian duty regarding slavery without waiting for recommendation from other meetings. The Philadelphia meeting of June 1716 censured Southeby and forced him to apologise for publishing unapproved pamphlets. By December 1718 they were warning him of disownment as he had retracted his apology and published a further paper on the subject.

For John Farmer the fight to stop Quakers owning slaves wasn’t the first time he had made a challenge against the status quo. Back in Saffron Walden in 1701 he had infuriated the local mayor and church-wardens for refusing to pay a combined tax for repairs to the church (which Farmer scathingly called a steeple-house) and poor relief. He was only prepared to pay for the portion relating to relief of the poor, and not for church maintenance, arguing he shouldn’t pay for a roof he didn’t worship under. He wrote letters and published pamphlets explaining why Quakers should not pay tithes and was so dogged in his protest that eventually the mayor gave in and accepted a reduced payment.

The people of Saffron Walden did inlarge ye poor tax On purpose yt there might bee thereby mony enough gathered for ye poor & for to repair ye steeple- house. Thus they put church tax & poor tax together & called it a rate for ye relief of ye poor. I was told yt heretofore ye church wardens of saffron walden had caused a friend to be excommunicated & imprisoned till death for refusing to pay to their worship house. Thus they put ye parrish to charge & their honist neighbour to prison without profit to themselves. Which troubled the people & therefore they go no more… When they demanded ye said tax of mee I could not pay it all because I know some of it as for their worship house. I offered to pay my part to ye poor: But ye overseer would not take it: excypt I would pay ye whole tax.[iv]

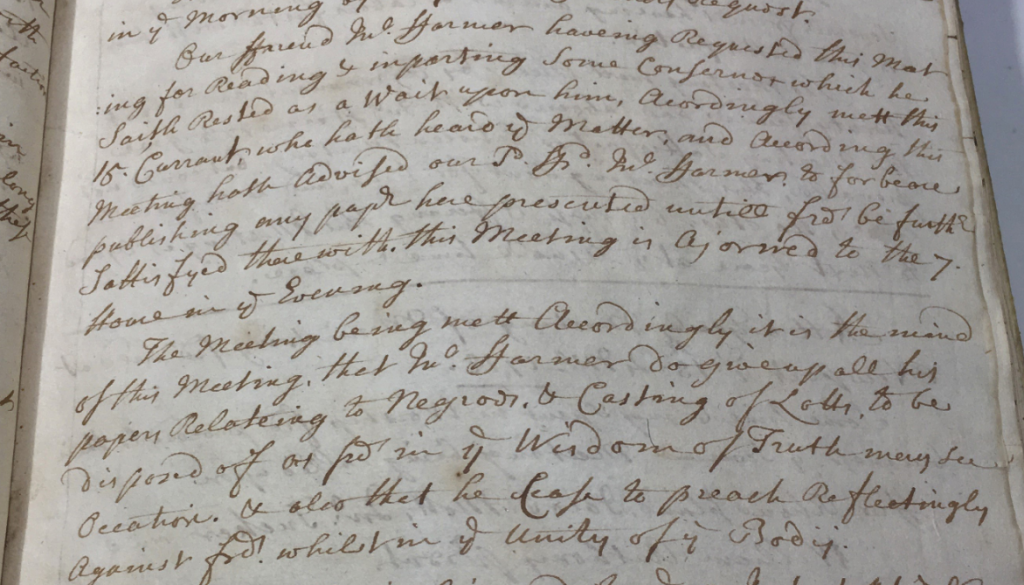

In April 1717 Farmer presented the Nantucket meeting with his pamphlet ‘Epistle Concerning Negroes’ deriding the Quakers for owning slaves, and it was received with satisfaction. Unfortunately the pamphlet has not survived, as far as we know. Obviously emboldened by the reception he had received in Nantucket, and with his customary fervour, in 1717 John Farmer requested a meeting of Elders and Ministers at the June Yearly meeting in Newport Rhode Island which took place on 4th June 1717 and there he presented them with two documents, one his ‘Epistle Concerning Negroes’, the other his criticism of ‘Casting Lotts’ (gambling) and his opinions were not well received by the audience there. They felt he was undermining unity and stirring up division which was unacceptable. As a result Farmer was disciplined for refusing to surrender his pamphlets and continuing to campaign. Records from the time report twenty Friends laboured with him overnight to encourage him to set aside his views. But he would not and the following morning they refused him access to meetings until he was prepared to back down which he never did. [v]

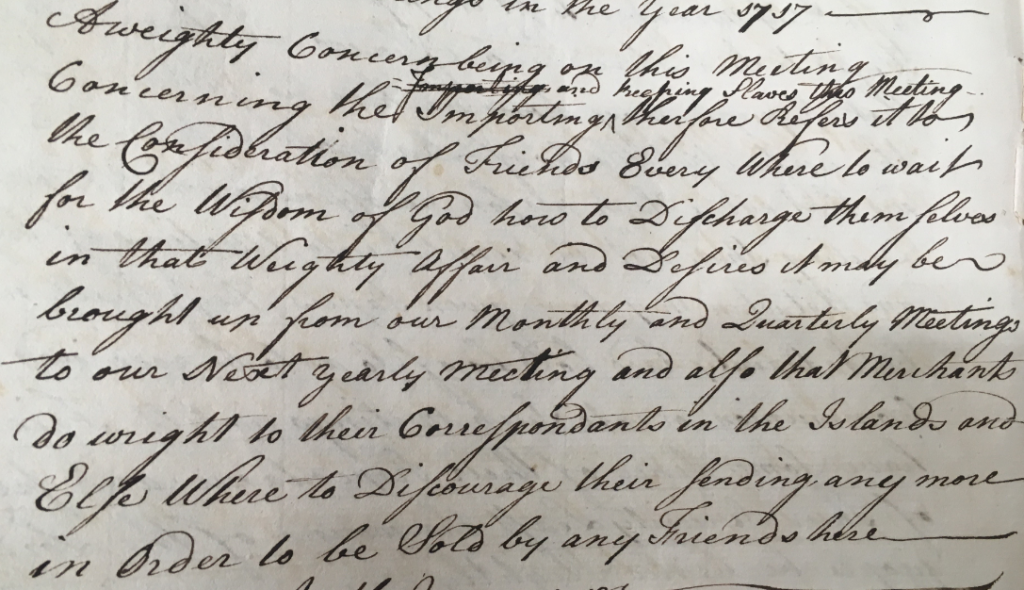

Minutes of the 1717 Newport Yearly meeting quietly record their decision on the subject of importing and keeping slaves as being to “wait for the wisdom of God how to discharge themselves in that weighty affair” but also that merchants should write to their “correspondents in the Islands to discourage them from sending anymore.” They would review it again at the 1718 meeting. That was as far as they were prepared to go.[vi]

The Friends of Philadelphia found it necessary to take subsequent action in the matter because John Farmer was undeterred and continued to disturb meetings, shouting over ministers and making a general nuisance of himself. He appealed to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting in July 1718, but the Yearly Meeting felt no good would come from listening to his complaints, and that he could not be received in unity until he had accepted his writings were unacceptable. When he refused to condemn his own work he was disowned. This seemingly harsh action by the Philadelphia Quakers appears to have been a matter of some embarrassment for years to come. John Farmer had been intemperate in his language, and impatient for change to be hurried through, but to the gentle Quakers he employed what was later described witheringly as “Indiscreet Zeal” in the Biographical Sketch published in the journal The Friend of 1855[vii]. The editor and author John Richardson says that

“his actions might have been suffered to have slept in oblivion if it were not that Friends of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting have been charged several times with silencing him, because of his testimony against slavery’. “

Presumably being disowned meant John Farmer lost access to the network of contacts he normally used to help him travel. He remained in America, perhaps too poor, or too ashamed to return to England or perhaps because he was determined to keep fighting for the anti-slavery cause. The Friend Journal ponders how he may have had more success.

“John Farmer may have rightly, as well as forcibly pled the cause of the slave. If, after doing this, he had left the matter to the great Head of the Church, and whilst proclaiming his truth had endeavoured to cultivate in himself love and good will to those who differed from him, he … would have done more towards advancing the cause dear to his heart than could have been effected by denunciation or irritating language.”[viii]

Farmer is recorded as being located in and around Philadelphia for the remainder of his life, holding small meetings of like-minded friends whenever he could and presumably continuing in his trade as a wool comber. He died in Germantown near Philadelphia in late 1724 or early 1725 at the age of about 57, having never made it back home to his family. In his will, written in August 1724, he left all his British possessions to his wife Mary, and his American possessions to his daughter Ann. He left instructions to the executors that they put:

“no new linen on my dead body, but my worst shirt on it, and my worst handkerchief on ye head and ye worst drawers or briches on ye body and ye worst stockings on ye legs & feet. And invite my neighbours to com to my house & there thirst in moderation with a Barrel of Sider & two gallons of Rum or other spirit.”[ix]

John Farmer may have been an old sober-sides, but he made sure he got a decent send off. Probate on the will was granted 11th January 1724/5.[x]

Thus the story of John Farmer the

Essex Quaker in America, comes to an end.

But in my last post we will look at the extraordinary women in John

Farmer’s life, his daughter Ann, step daughter Mary Fulbigg and especially his wife

Mary Farmer all had a role to play in the wider story of this man and their

stories also deserve to be told.

[i] Letter John Farmer to Mary Farmer dated Virginia 1706. Essex Record Office Cat D/NF 3 addl. A13685 Box 51

[ii] See my previous post An Essex Quaker in the Caribbean for more information.

[iii] Quoted in Drake, T.E., Quakers & Slavery in America, Oxford University Press, London 1950 p. 28

[iv] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p.56

[v] New England Yearly Meeting: Committees: Ministry: Minsters and Elders, 1707-1797. New England Yearly Meeting of Friends Records (MS 902). Special Collections and University Archives, UMass Amherst Libraries.

[vi] New England Yearly Meeting: Administrative Minutes, 1672-1735. New England Yearly Meeting of Friends Records (MS 902). Special Collections and University Archives, UMass Amherst Libraries

[vii] The Friend, J Richardson (Ed) Vol XXVIII, Vol 40 page 316, Philadelphia, 1855

[viii] The Friend, J Richardson (Ed) Vol XXVIII, Vol 40 page 316, Philadelphia, 1855

[ix] Philadelphia County Wills: The Will of John Farmer (1724) – Copy in Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51

[x] Philadelphia County Wills: The Will of John Farmer (1724) – Copy in Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51