In the second post focusing on Black histories at the Essex Record Office, we’ll explore some of the audio recordings preserved in the Essex Sound and Video Archive (ESVA). Including broadcasts on local radio, spoken-word poetry, and oral histories, these recordings give us an insight into the experiences of a diverse range of Black people in Essex over the past 75 years, right up until the present day.

You can explore the Black History Month display and listen to more clips in our Searchroom – check our website for opening hours.

Unfortunately, the earliest recording in the ESVA relating to Black history – a race relations meeting held at St Martin’s Church, Basildon, in December 1968 – is very poor quality, largely due to the acoustics of the venue (SA 20/2/37/1). More audible recordings can be found in the archive of BBC Essex, which broadcast events, discussions, and features across the county from 1986. While there were no programmes produced specifically for Black or ethnic minority audiences (as there were on other local radio stations outside Essex), the archive does include some recordings that help us to understand the experiences of the Black community during this period.

The clip below is from a radio programme about the work of Thurrock Community Relations Council, broadcast in 1988. The council aimed to “promote harmony, eliminate racial and cultural discrimination, and promote equal opportunities” in the area, and included representatives from the local Sikh, Vietnamese, and African-Caribbean communities. The speaker in the clip is Diana Wall, who had moved to the UK from Guyana in the 1960s and was working as a midwife in Grays.

“The older people accept me as a person in my field of work, but the younger generation sometimes do cause a little bit of a problem.”

Voices from Black communities across Essex continue to be recorded for broadcast today, both by BBC Essex and organisations like the Essex Cultural Diversity Project (ECDP), which launched ECDP Radio in 2021. In episode below, presenter Nita Jhummu talks to Sangita Mittra, Wrenay Raphael and Carlos Byles from the New Generation Development Agency, about Black History Month in Chelmsford (SA 74/2/7/1):

Other contemporary reflections on issues of identity and place have been commissioned by Focal Point Gallery in Southend-on-Sea for FPG Sounds, an online project supporting the development of new sound works by artists from or based in Southend, now archived in the ESVA (SA912). Amongst the fifteen commissions are several spoken-word pieces by Carrissa Baxter and The Repeat Beat Poet (Peter deGraft-Johnson), exploring Black British history and their own experiences.

The Repeat Beat Poet’s poem ‘One Black Lotus’, inspired by the eighteenth century Jamaican-Scottish radical and union activist William Davidson.

Over the last fifteen years, museums, arts organisations, and artists have also recorded the stories of people who moved to Essex from the Caribbean in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as more recent experiences of those with African or Caribbean heritage.

Oral histories are some of the most powerful records of recent Black history in Essex. As historians have shown, the fact that the personal experiences of people of African descent in Britain have not generally been recorded – as we found in the first blog post – has contributed to their historical erasure. In contrast, oral histories give people the opportunity to share their stories in their own words. Quoting from the 1991 Julie Dash film, Daughters of the Dust, Dr Meleisa Ono-George has emphasised that “there is power in the knowing, but there is also power in the telling”. As the artist Everton Wright (EVEWRIGHT) describes in the clip below, the richness and complexity of these stories also provides a foundation for future generations to listen to and learn from.

In 2008, staff at Hollytrees Museum in Colchester recorded oral histories with nurses who came to work for the NHS from around the Commonwealth, including the Caribbean, for the exhibition ‘Empire of Care’. In the recordings, the interviewees talk about their memories of arriving in Essex, training to be nurses, living in Colchester during the late 1950s and 1960s, and their careers since.

Looking back over their lives, they also reflect on their achievements and the challenges they faced. In the clip below, Shirla Philogene (née Allen) describes her experience of ‘colour prejudice’ during her nursing training in Colchester. Shirla grew up in St Vincent & the Grenadines and started her training in Colchester in 1959. She received an OBE for her services to nursing leadership and development in 2000 and published a book about her experiences, Between Two Worlds, in 2008.

Another interview with Shirla is preserved in the Royal College of Nursing archive (T/374), and you can hear more clips from the interviews with Shirla, Ester Jankey, and Rosie Bobby in this blog post about the collection.

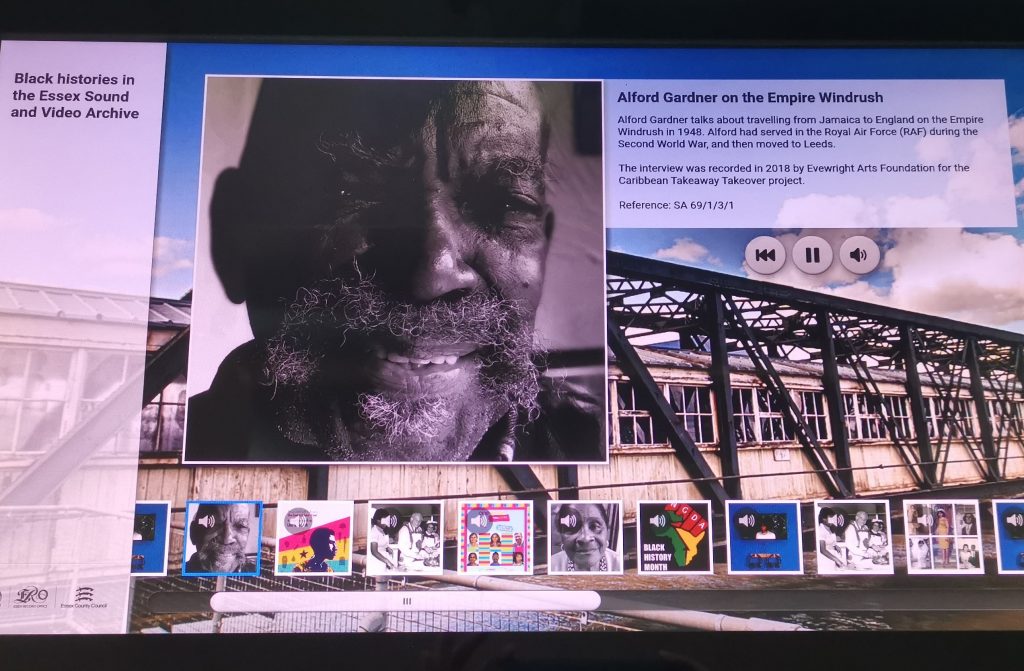

Between 2017 and 2018, EVEWRIGHT and Evewright Arts Foundation recorded thirteen oral histories with Caribbean elders across Essex. Ten-minute excerpts from the interviews were played as part of the Caribbean Takeaway Takeover exhibition at the S&S Caribbean Café in Colchester on the weekend of the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush at Tilbury. As with the ‘Empire of Care’ recordings, many of those interviewed describe their journeys to the UK from the Caribbean. One interviewee, Alford Gardner, travelled from Jamaica on the Windrush itself:

” When we came here, reach Tilbury, there were two Calypsonians from Trinidad and any part of the boat you walk on I mean, some little ting, ting ting, ting, ting t-ting-ting. Anything that moved on the boat, a song was made up about it!”

Alford Gardner speaking to Ionie Richards and Everton Wright in 2018 (SA 69/1/3/1)

Importantly, the oral histories record the many different experiences of the pioneers now known as the ‘Windrush generation’, and their lives in the UK beyond the point of arrival. In this clip, Alton Watkins, who passed away in May this year, reflects on his contribution to British society as a teacher and England being his home.

In 2020, EVEWRIGHT created a new installation in a passenger walkway at the Port of Tilbury. The 432 panes of glass along the walkway are collaged with photographs, passports, documents, boat passenger tickets and memorabilia. There is also a series of sound windows, where visitors can listen to some of the audio stories recorded for the Caribbean Takeaway Takeover installation, as well as new interviews recorded by Evewright Arts Foundation and donated by members of the public across the UK. The clip below is from an interview with Freda Seaton, where she describes moving to the UK from Jamaica in 1957.

This series of recordings was deposited in the ESVA earlier this year. Thanks to the generosity of the participants, we are delighted to be able to share them on our catalogue, Essex Archives Online, and our Soundcloud channel. You can also pick up a legacy publication about the installation in our Searchroom.

Another collection of recordings recently deposited in the ESVA is a series of four conversations recorded by the artist Elsa James in 2019 for ‘Black Girl Essex’, a project carried out during her four month residency for Super Black, an Arts Council Collection National Partners Programme exhibition at Firstsite in Colchester (SA 78/1).

The thirteen participants in the conversations represent the diversity of the Black community in Essex in the twenty-first century. They varied in age, from 13 to 74, and while some moved to Essex as children, or later on in life, others were born and brought up in the county. This diversity is reflected in the recordings, as they discuss their perceptions of Essex, whether the Essex stereotype resonates with them, and their experiences of being othered.

One of the participants was the actor and director Josephine Melville, who sadly died on 20 October. Jo set up the South Essex African Caribbean Association (SEACA) in 2012 and was passionate about bringing communities together to celebrate their culture and heritage. As well as the interview with Elsa James, Jo was also involved with EVEWRIGHT’s Tilbury Bridge Walkway of Memories project, to which she contributed a recording of her parents’ experience of moving to Britain from Jamaica, and a conversation with her mother, Byrel.

In this excerpt from her conversation with Elsa, she reflects on the importance of recording and preserving Black histories in Essex.

“Moments need to be logged and treasured, so that we don’t get lost, and that our history and our presence in this area are not just told by other people, they’re told by us.”

Josephine Melville speaking to Elsa James, September 2019