John Crellin, Archive Assistant

Love it or loath it, football has always had the power to hit the headlines. An article from the ERO’s historic annals of the Essex Chronicle describes an off-pitch outbreak of communal violence associated with the ‘beautiful game’ in Victorian times.

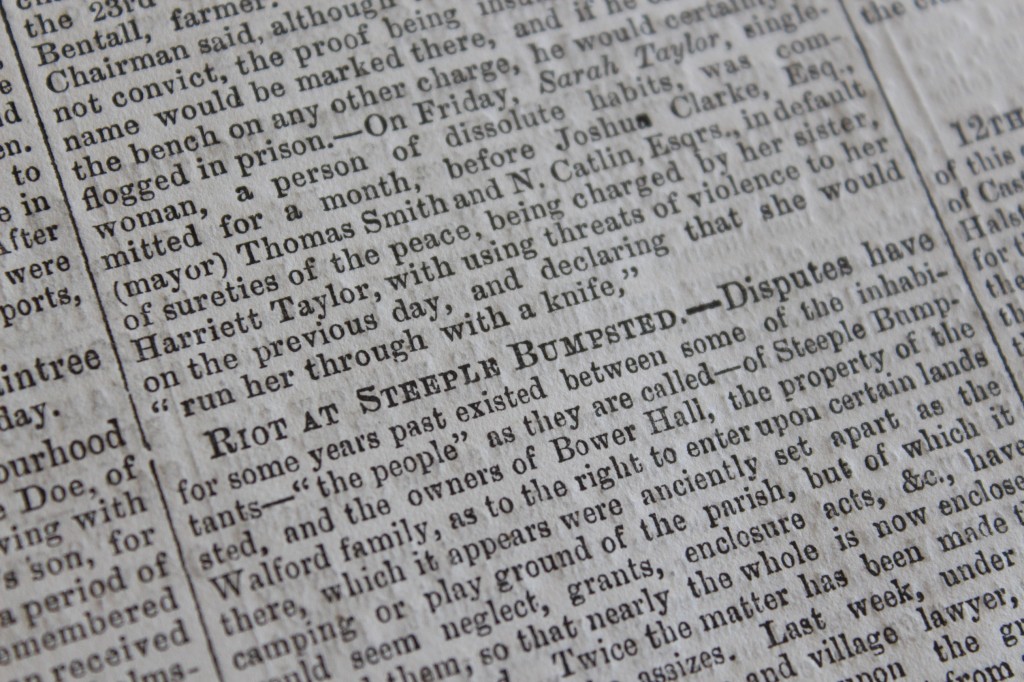

On Friday July 19, 1861 the Chelmsford Chronicle, forerunner of the Essex Chronicle, dramatically headlined a story ‘Riot at Steeple Bumpstead’. What followed was a detailed account of court proceedings recording violent clashes between rioters and the police in the normally peaceful village of Steeple Bumpstead.

Parishioners of Steeple Bumpstead had enjoyed the privilege of playing games of various kinds on an area of land in the village known as the Camping Close.

The close was said to be part of the land given to the parish by William Helion centuries ago and leased to the Lords of nearby Bower Hall.

Over the years the area had gradually reduced with the taking over, or enclosure, of sections of it by the Bower Hall estate for agricultural purposes.

Keen on their football, the villagers objected and various incidents of trespass resulted in a boundary, in the form of a ditch, being dug in 1849 by John Snape, then the tenant of Parsonage Farm (part of the Bower Hall estate), to cordon off a part of the Camping Close for his own use.

In the eyes of the villagers this was wrong. Snape was encroaching on their playing field.

In 1860 (with Snape gone and William Dere now tenant of the farm) their unhappiness resulted in some notable foul play when John Clayden, John Salmon and John Bunton, all described as ‘young tradesmen of Steeple Bumpstead’ moved a pile of manure from the area behind the boundary ditch and scattered it over Camping Close land. Later they returned with 20 fellow villagers to play football over the land, in the process treading the manure into the ground.

The three were brought before the magistrate’s court and charged with the offence of damaging a pile of manure. They were found guilty and fined a shilling.

The villagers firmly believed in the ancient rights and the case went to appeal at the Court of the Queen’s Bench. Here the conviction was quashed on the grounds that there was ‘reasonable supposition of right’ on the part of the defenders.

A short time later, encouraged by the verdict, John Bunton, a one-armed veteran of the Crimean War of the 1850s, William Woodham, William Spencer and Charles Willis overthrew a corn rick standing on the disputed area. As a result they were served with a writ by William Dere, to prevent further damage.

Incensed by the issuing of these writs, in the summer of 1861 a large crowd of villagers led by a man described as a ‘warlike veteran village lawyer’ entered another area of disputed land cutting down a hedge and 74 trees from a plantation.

Warrants for the arrest of the five men considered to be the ring leaders were issued, but when the local policeman Constable Robert Spencer tried to execute the warrants he and his colleagues were met with ‘forceful’ opposition amounting to a riot. In the face of such opposition the constabulary withdrew leaving the villagers in command of their Camping Close.

The rule of law was upheld the next day with the arrival of John McHardy, the Chief Constable. He met with the leaders and managed to persuade them to attend court in Castle Hedingham.

They were committed for trial at Chelmsford Assizes and led to Springfield gaol. John Claydon, 18, shoemaker, Charles Willis, 21 labourer, William Spencer, 18, baker, William Woodham 21, labourer and John Bunton, 25, labourer, were all indicted for their symbolic act of defiance in feloniously damaging trees in a plantation adjacent to Bower Hall Park.

The jury found the Steeple Bumpstead five guilty and the judge imprisoned them for one month without hard labour and to be bound over to keep the peace for two years.

Historic newspapers provide a never-ending supply of interesting, odd and surprising details about life in the past, and it’s easy to get lost in them for hours. If you fancy doing just that, make the most of free access to the British Newspaper Archive Online in the ERO Searchroom or Essex Libraries.

A version of this article was published in the Essex Chronicle in 2004 but it was such a good story we thought it was worth sharing again.