Archivist Lawrence Barker talks us through his choice for December’s Document of the Month.

This month’s document is a remarkable music book surviving from Elizabethan England (D/DP Z6/1). It is part of the collection of the Petre family, who lived at Thorndon Hall and Ingatestone Hall. The Petre family remained Catholic throughout the upheavals of the English Reformation, as Catholics were increasingly marginalised in a newly Protestant country.

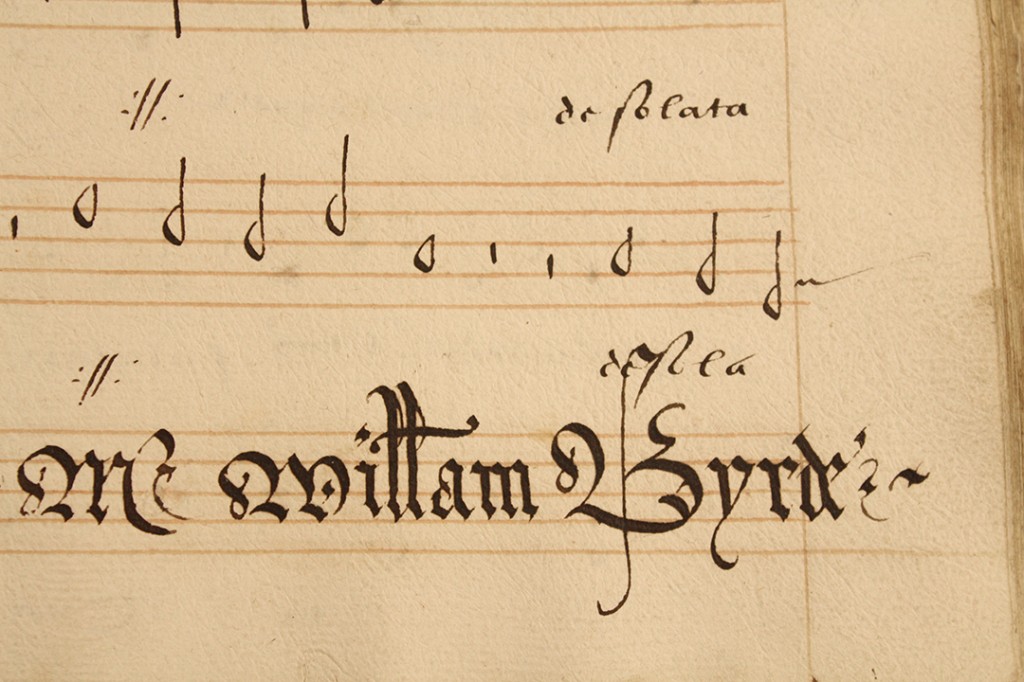

The book contains mostly motets (short pieces of sacred choral music) by English composers such as Thomas Tallis, Robert Wight, Robert Fairfax and William Byrd, who flourished in the mid-16th century. From 1595 Byrd lived nearby in Stondon Massey, and is known to have spent time at Ingatestone Hall. There are also a few pieces by other European composers such as Palestrina and Philippe de Monte.

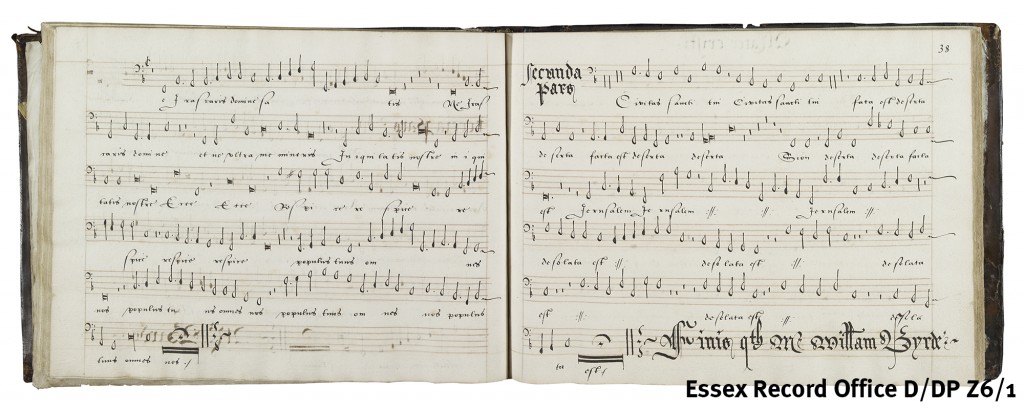

The book will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout December 2015, open to one of Byrd’s finest motets, Ne irascaris Domine (Be not angry, O Lord).

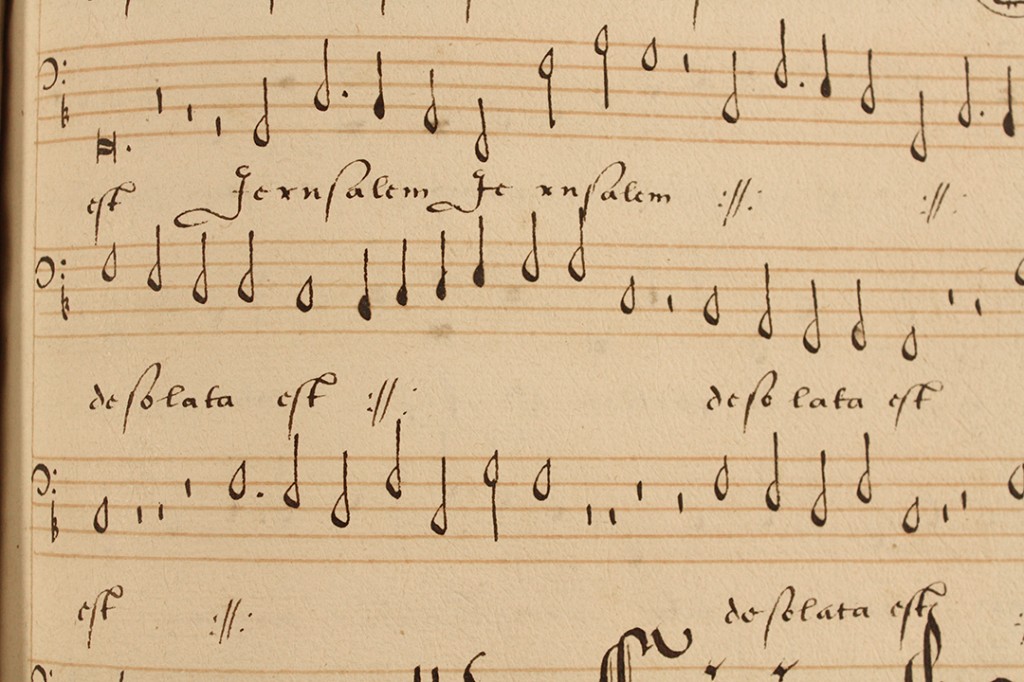

Part of William Byrd’s motet Ne irascaris Domine in a sixteenth century music book from the Petre collection (D/DP Z6/1)

To bring the music in this book to life, a modern edition of this piece was recently performed by Essex choir Gaudeamus.

The music was written to be performed a cappella, i.e. in the ‘chapel style’, sung by voices unaccompanied by instruments. Singers today use a music score showing all the different parts of the music (you can see an example of the piece shown above, Ne irascaris Domine, here), but in Tudor times each voice sang from its own part book showing only their line. This book contains only the bass part (for the lowest voice) for pieces which would have had five parts altogether. The question arises: what happened to the other part books which seemingly have not survived?

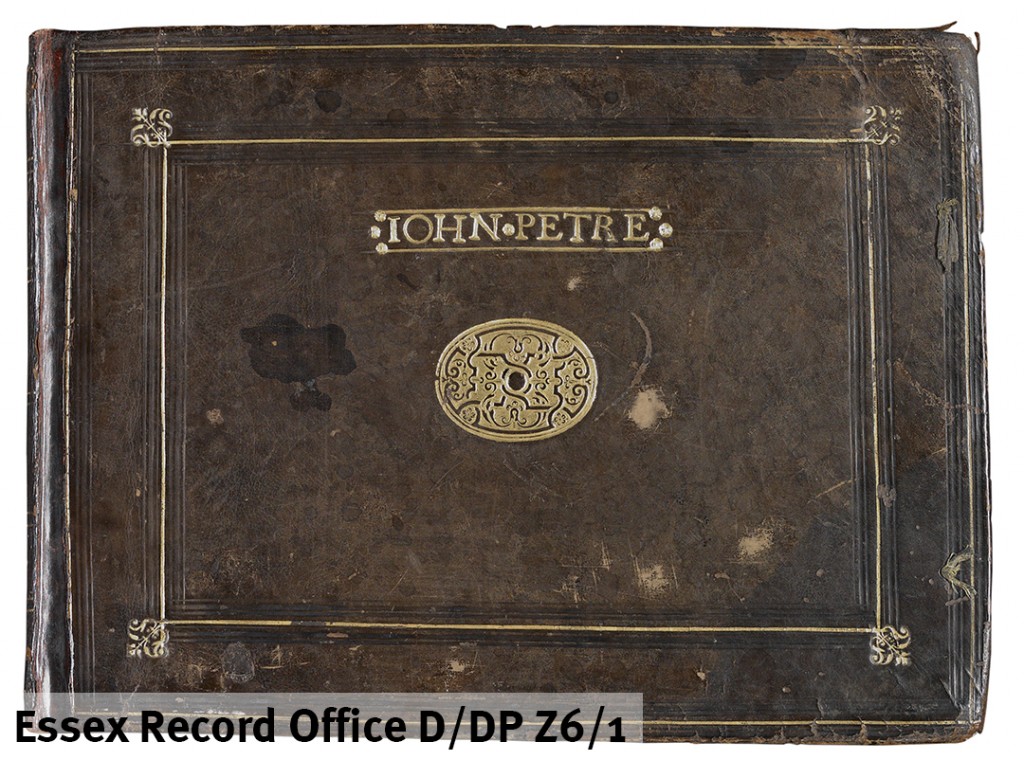

The front cover of the book has the name John Petre embossed upon it in gold, suggesting that the book belonged to the first Baron Petre himself (1549-1613). The music seems to be a personal selection and includes some of the choice pieces from the golden age of English Roman Catholic church music, such as Tallis’s Lamentations, the same by Robert Wight, as well as many of the great motets by Byrd.

The front cover of the book is embossed with John Petre’s name, the first baron Petre, suggesting that it was his personal book

There is not an exact date for the book but none of the music in it dates from after 1591. Much of Byrd’s music, including this motet, was published during his lifetime; indeed, he and Thomas Tallis were granted a publishing monopoly on music by Elizabeth I. This book, however, is not a printed, published edition but is hand written. It is a substantial book and it must have taken someone many, many hours to complete.

The texts are all in Latin which suggests that the book was written for use in Roman Catholic services. Much of the music dates from earlier in the 16th century and some of it might have been written originally for the Catholic queen Mary Tudor. In the case of the pieces by Byrd, however, the music was probably written to be performed in the Chapel Royal for the Protestant Elizabeth I, who seems to have retained a ‘High Anglican’ taste for Latin church music. Despite being a Catholic, Byrd was part of the choir of the Chapel Royal and would have sworn an oath when he joined in 1572 recognising Elizabeth as head of the English Church.

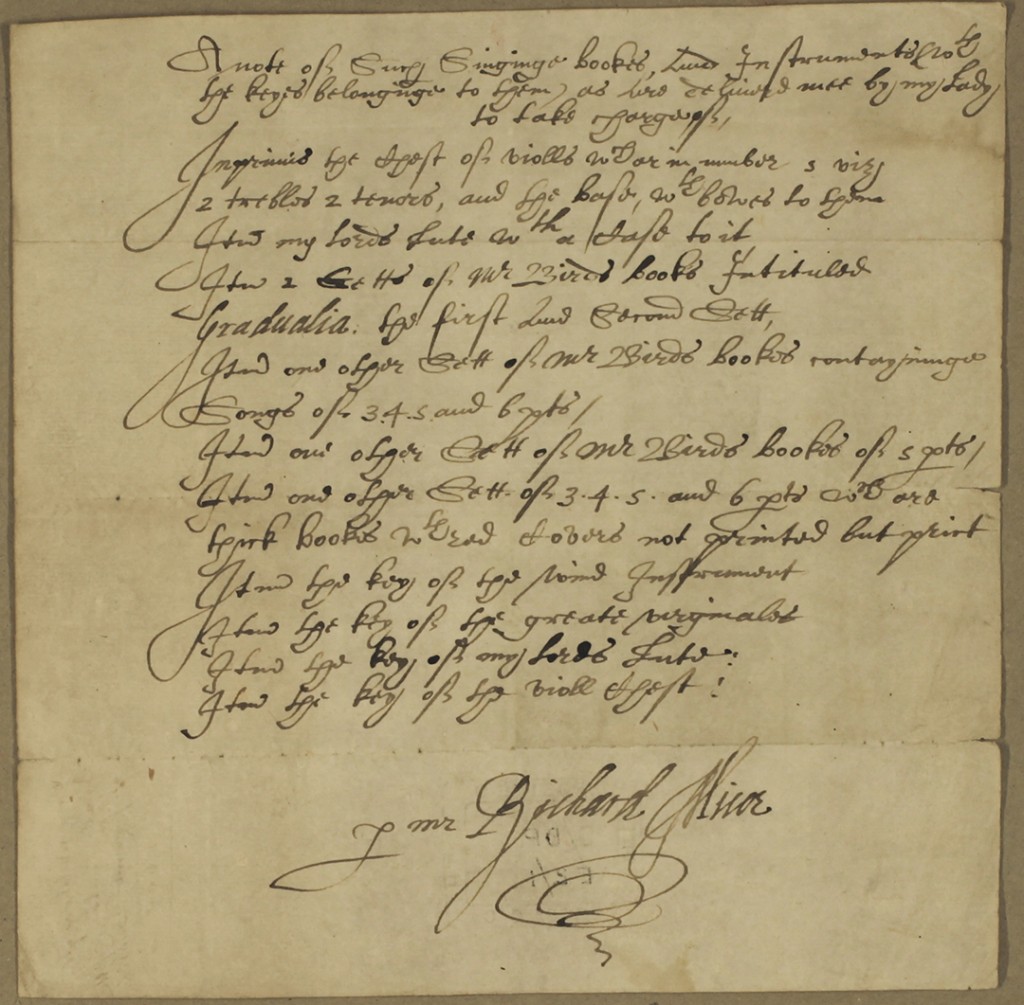

Most of the music in the book is choral, but there are also a few instrumental pieces which would have been played on viols, stringed instruments that look somewhat like those of the modern violin family. As well as singing there would have been instrumental music in the Petre household; there is a suggestion that John Petre himself may have played the lute, as an inventory of 1608 lists ‘my Lord’s lute’ among other instruments including an organ, double virginals and a chest of viols. It also lists various sheet music described as ‘Mr Birds bookes’, including a set of books in five parts, described as ‘thick bookes with red covers not printed but prict [pricked – or handwritten]’. These music books likely include the ones that today are at ERO.

An inventory of 1608 recording pieces of sheet music and various musical instruments owned by the Petre family (D/DP E2/1)

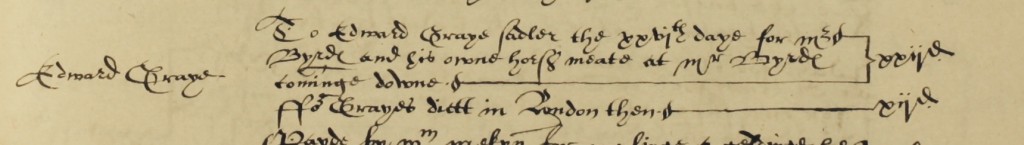

The music book and the inventory show that the Petre family indulged in some serious music-making, a point further evidenced in the account books that survive for this period showing that Byrd was frequently involved. For example, the accounts book for 1589-1590 (D/DP A21) shows that Christmas 1589 must have been a merry affair for the Petre family involving lots of eating, drinking and music making. William Byrd was fetched from London by the ‘sadler’ Edward Graye on Boxing Day (below), and there were five other musicians from London ‘playing upon the violins’ (i.e. the set or ‘chest’ of viols) who stayed until Twelfth Night.

The motet by Byrd featured above, Ne irascaris Domine, was published in 1589 as part of Cantiones Sacrae I (Sacred Songs I). The music portrays a dark time for English Catholics when, following the Spanish Armada in 1588, many Catholics like the Petres and Byrd were persecuted for their faith. This motet, like many others in the collection, is in two parts.

The first part starts, ‘Be not angry, O Lord, remember no longer our iniquity. We are all your people’ (Isaiah 64:9). Was this a recusant Catholic’s subliminal plea to Elizabeth herself which she would have heard when it was sung to her in the Chapel Royal? Significantly, only three years later in 1592, a charge of recusancy brought against Byrd was dropped ‘by order of the Queen’.

The second part of the motet is more desolate: ‘Thy holy city is made desolate. Zion is made desolate. Jerusalem is forsaken’ (Isaiah 64:10). Of course, ‘Jerusalem’ was then, and has been many times since, a symbolic name for England. The motet gives a beautiful example of polyphony, where melodic lines interweave with each other yet maintain perfect harmony, a common feature of sacred music of this period. Byrd creates a marked effect, however, by changing from the general polyphony at the words Sion deserta facta est (Zion is made desolate) (approx. 05:30). After a short pause, all voices sing in solemn chords as in a hymn. When the polyphony resumes, the choir repeats ‘Jerusalem’ and ‘desolata est’ over and over again until the end, as can be seen in the manuscript showing the bass part.

Music such as this would have been part of a very specific, even élite soundscape. The majority of ordinary Elizabethans probably never knew Byrd’s music unless they were servants in Lord Petre’s household or Byrd’s, or happened upon it when attending a service in a cathedral, such as Lincoln where Byrd’s music is known to have been performed. Even among the élite, much of Byrd’s music would have been exclusive, limited to a few patrons. Byrd himself made no bones about the intellectuality of the music itself. However, he did publish much of it, and that would have increased its accessibility to those who came to know of it, could afford to buy it and were able to perform it.

Today, with recorded sound, we have much greater access to all kinds of music. Recorded music is ubiquitous, a constant background noise in shops, pubs, or buses via fellow passengers’ headphones.

We are fortunate that the written music survives, as we can recreate the sound of Byrd’s music, more or less, and in doing so transport ourselves back to the soundscape of Elizabethan England, or even specifically that corner of Elizabethan Essex where Byrd spent Christmas in 1589. Almost everything that Byrd wrote has now been recorded, some of it many times. If we lived in Ingatestone today, we would only have to load our CDs or search YouTube to listen to Byrd 24/7 if we so desired.

The music performed by Gaudeamus has been transposed up to a higher pitch to accommodate a mixed rather than all-male choir. Nevertheless, being sung in a church that partly dates from the medieval period, we can imagine that hearing it resembles the musical experience of our predecessors. However, there are limits to how far we can experience historic soundscapes.

Today, with recorded sound, we can capture much more precisely the noises around us. The Essex Sound and Video Archive collects and preserves recordings such as this performance for future generations to enjoy. For our Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place, we will be making many of our recordings available online. Why not listen to this piece while sitting in the grounds of Ingatestone Hall, or Stondon Massey, to imagine what the song would have sounded like to its composer?

For further information on You Are Hear and how you can contribute your own recordings, look at our blog page or visit our website.

Ingatestone Pedallers Social Cycling Group visited Stondon Church this year on 28 June and by chance arrived as the church wardens where still clearing up from the morning service and were able to peal the bells, with a little bit of help. Quite a special privilege for a group from Ingatestone, and for a Byrd admirer like myself, it will always be remembered.