Have you ever had an ear-opening moment?

This was a phrase used by legendary wildlife sound recordist Chris Watson in a keynote address delivered at the Sound+Environment Conference hosted by the University of Hull in June 2017. He used it in his narration of his personal journey into his career as a sound recordist, and it struck a chord. Have you ever experienced a moment where the soundscape was so startling, unexpected, beautiful, quiet, or loud that it opened your ears and heightened your awareness of the sounds around you?

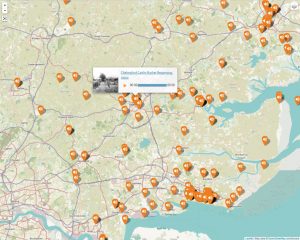

The Essex Sounds audio map,  developed as part of our Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place, could provide moments like that. Although you can listen to sounds recorded across the county from an enclosed, familiar location, browsing the Web at home or in a library, we hope it will spur you on to take greater notice of the sounds of your Essex in your daily routine: whether natural or man-made; everyday or unusual; familiar or unidentified. Do the sounds on the map reflect your own experiences, or does your Essex sound very different?

developed as part of our Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place, could provide moments like that. Although you can listen to sounds recorded across the county from an enclosed, familiar location, browsing the Web at home or in a library, we hope it will spur you on to take greater notice of the sounds of your Essex in your daily routine: whether natural or man-made; everyday or unusual; familiar or unidentified. Do the sounds on the map reflect your own experiences, or does your Essex sound very different?

The free app version of Essex Sounds (available from Google Play or Apple IStore) allows more direct comparisons between the sounds on the map and present moment experiences. Travel to the location of one of our historic recordings from the Archive; play the sound; then take a few moments to listen to the present-day soundscapes. What are the similarities and differences? Is one quieter or louder? What does that tell us about broader changes in Essex?

The Sound+Environment Conference was full of presentations on how to encourage active listening. We learn to filter sounds because our atmospheres are so noisy. We tune into the sounds that we like (a loved one’s voice, the music coming through our headphones) or that give us important information (alarms, tannoy announcements) while ignoring those we do not (traffic, the music coming from other people’s headphones). But sometimes, it is enlightening to open our ears, notice the full range of noises around us, and contemplate what those sounds tell us about our environment.

The Conference was truly interdisciplinarian – there were even one or two other archivists in attendance. Many of the presenters were involved in acoustic ecology: judging the health of ecosystems based on the sounds that they make. For example, Dr Leah Barclay’s River Listening project seeks to collect data from hydrophones placed in rivers across the globe. What can the sounds tell us about the diversity of the ecosystems, and what, in turn, does that tell us about the condition of the water? Many presenters, like Stuart Bowditch who co-presented our paper on Essex Sounds, were sound artists: using varying combinations of field recordings, musical instruments, and technology to capture, mix, and remix soundscapes to make an artistic statement. Others were interested in merging the two disciplines to strengthen the field of ‘ecological sound art’ (as argued by Jono Gilmurray). The power of sound can move us to respond, initiating the culture change that ecologists warn is vital if we are to preserve ecosystems threatened by our current way of life.

For example, how do you feel after listening to the pounding sea in Stuart’s recording made at Bradwell-on-Sea?

Or after hearing the number of peaceful recordings interrupted by aeroplanes rumbling overhead? Or after attentively listening to the baby owls in Joyce Winmill’s 1974 recording in Henham churchyard, an eavesdropping through time made possible by the simple technology of a microphone and tape recorder?

How does this make you feel about your Essex, how it has changed, and how it might change? What do you want your future Essex to sound like, and how do you make that happen?

Perhaps we think it is only far-flung landscapes like the Arctic Tundra or the depths of the oceans that demonstrate the majesty of nature which we must preserve. If you are thinking along those lines, stop what you are doing and open a window. Wait. Listen. What sounds do you hear? Essex Sounds is full of birdsong: some, yes, recorded in secluded environments such as wildlife reserves, but some just captured in towns, in the midst of our everyday lives.

This, too, is nature that might have changed and might change in future.

Neither is it just natural sounds that indicate change over time. Changing human activity is also evident on our sound map. Some industries have only moved. Others have largely disappeared, machinery laid to rest in museums, only resurrected for special events.

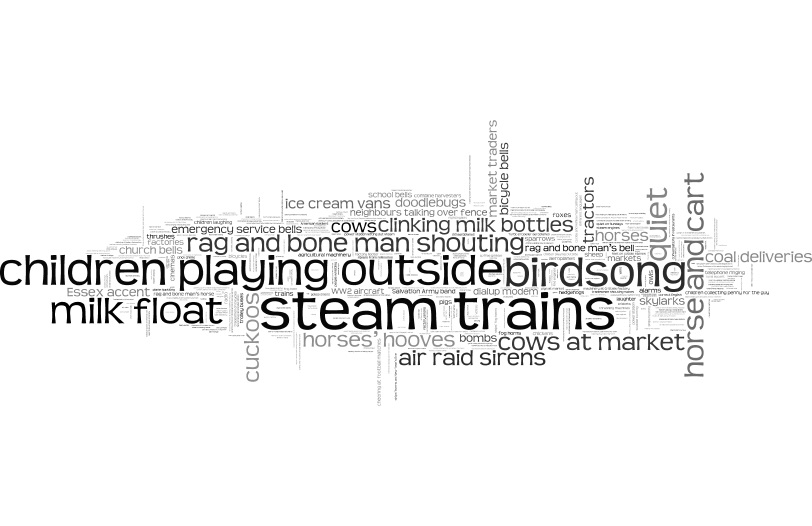

Perhaps you can identify with this collection of ‘lost sounds of Essex’, collected in 2015 when we asked people which sounds they no longer hear (Word Cloud created at Wordle.net).

What other changes become apparent from playing with Essex Sounds? Is there some vital sound that is missing from the map? Please help us make it more representative by adding your own contributions. Or perhaps you are a sound artist inspired by our collection of historic and modern sounds. We would love to hear ideas about how we can reuse these sounds and present them in new ways.

But above all, please take time to listen to the present-day Essex. Wake up five minutes earlier to allow time to listen before you start your day. Pause in your commute. Think again before popping on headphones. Close your eyes and open your ears.

Would you be interested in a sound walk event around Essex, which would incorporate an introduction into active listening, making sound recordings, and editing the results? We are running a survey to gauge interest in such an event. Please let us know what you think, and you could win a discount on the ticket price.