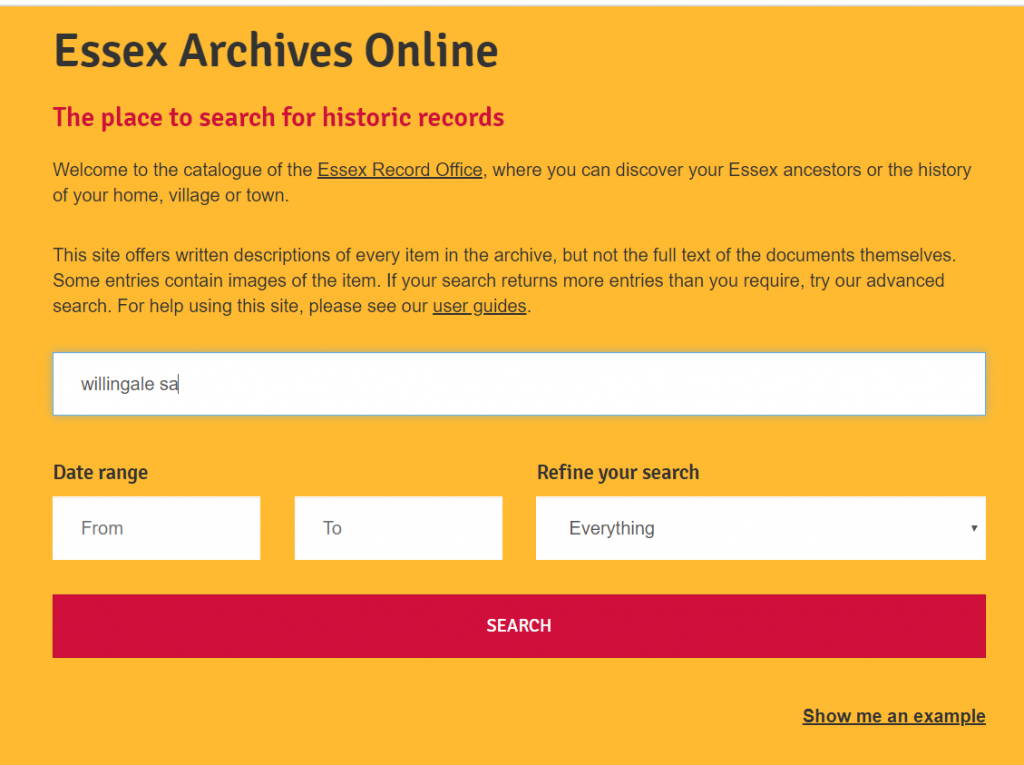

Archive catalogues can be difficult to use. There are differences between structured archive catalogues describing archival records that comply with the international cataloguing standard (ISAD-G) and a free-text Internet search box. While the homepage of Essex Archives Online looks like a basic text search box, using it like an Internet search engine will not give the best results.

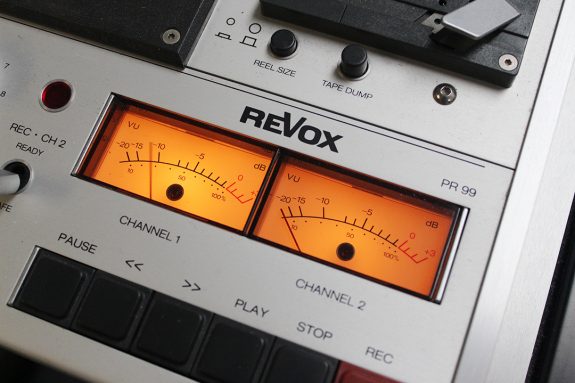

Part of the Heritage Lottery Funded project, You Are Hear: sound and a sense of place, involves cataloguing some of the thousands of unique sound and video recordings in the Essex Sound and Video Archive (ESVA). Cataloguing the records makes it easier for users to locate relevant material, but only if the catalogue descriptions can be found. We try to catalogue with discoverability in mind, but we thought it might be useful to share some tips on how to find sound and video archives in particular through Essex Archives Online.

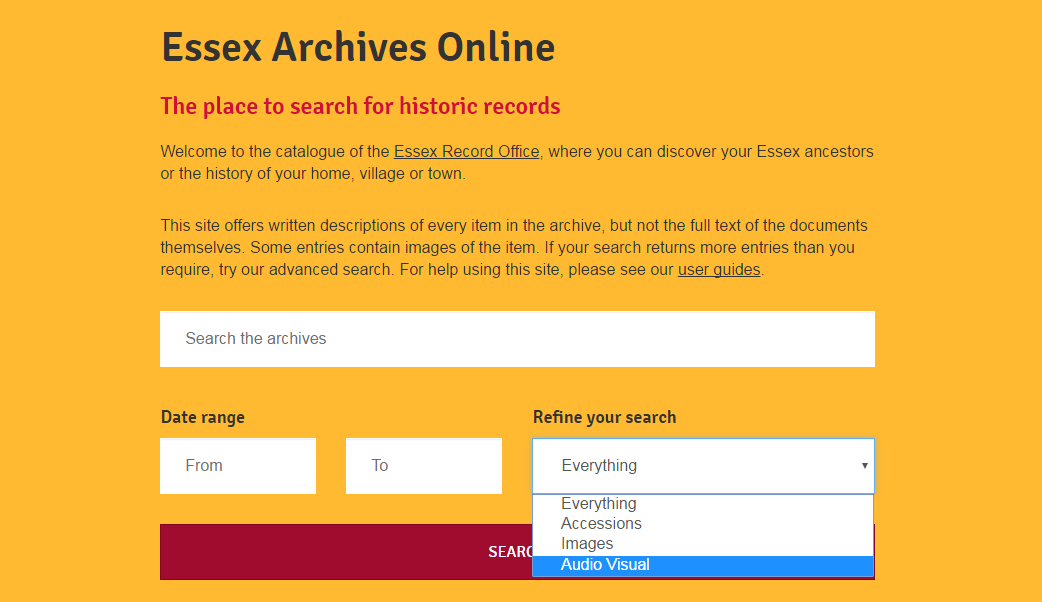

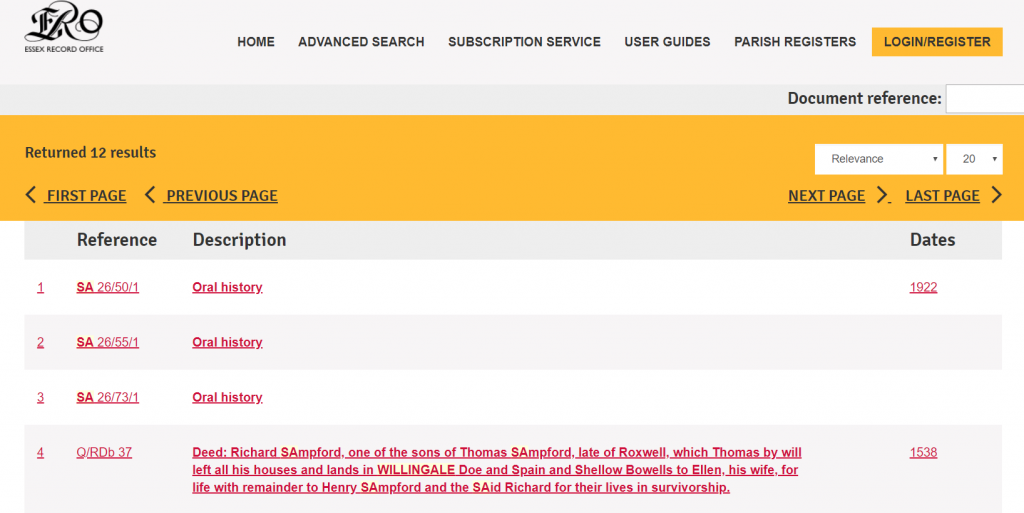

As reported in an earlier blog entry, we updated Essex Archives Online to allow you to play sound and video recordings directly through the catalogue. To find these recordings, select ‘Audio Visual’ in the ‘Refine your search’ box, and then type terms that interest you into the main text box. You will need to create an account and log before you can play the recordings, but you do not need to subscribe.

Tip: To browse all the sound recordings currently uploaded to the catalogue, select ‘Audio Visual’ in the ‘Refine your search’ box, then type ‘sa’ in the main search box. To browse all the video recordings, select ‘Audio Visual’ in the ‘Refine your search box’, then type ‘va’ in the main search box. We can explain why this works if you are interested, but otherwise just trust us that it (mostly) works!

However, we can only gradually upload digitised recordings to the catalogue. Also, copyright on some of the recordings prohibits us from making them available online. This means that we have many, many more sound and video recordings which cannot be played through the catalogue, but only by ordering them to play in the Playback Room at the Essex Record Office (or by purchasing a copy). These recordings won’t show up if you refine your search only to ‘Audio Visual’ records. So how do you find something in the ESVA that might be of interest to you?

When we catalogue material, we give each document or recording a Reference Number. This helps to uniquely identify the recording. It’s not a random collection of letters and numbers (though it might seem like it!): each part gives clues about the document and how it fits with other material.

The Reference Numbers for all sound recordings start with ‘SA’, for ‘Sound Archive’. So the easiest way to narrow your search to find sound recordings is to include ‘sa’ as one of your search terms.

Similarly, the Reference Numbers for all video recordings start with ‘VA’, for ‘Video Archive’. To find video recordings, include ‘va’ as one of your search terms.

Tip: You will still get some results that are not sound or video recordings. Change the sort by box at the top-right to ‘Reference’. This will display your results in alphabetical order by Reference Number. Scroll down to the Reference Numbers that begin with ‘SA’ or ‘VA’.

So far so good, but how do you know what to search for? Unlike the majority of the documents in the Essex Record Office, you might find some ESVA recordings by searching for an individual’s name. If the individual has been recorded in an oral history interview, or featured in a local radio piece, then his or her name should be included in the catalogue entry.

But you will probably find more results by searching for a place or subject. For example, perhaps you want to learn more about how Willingale has changed over time. If you type in ‘Willingale’ and ‘sa’ in the search boxes, you will find eleven sound recordings, mostly oral history interviews with long-standing residents.

These might reveal information about local businesses, notable local families, services in the village – and especially people’s memories of the American servicemen stationed nearby during the Second World War.

Tip: Our search engine is not case sensitive. This means it does not matter whether you type ‘Willingale’, ‘willingale’, ‘WILLINGALE’, or ‘WiLliNGalE’: it will come up with the same results.

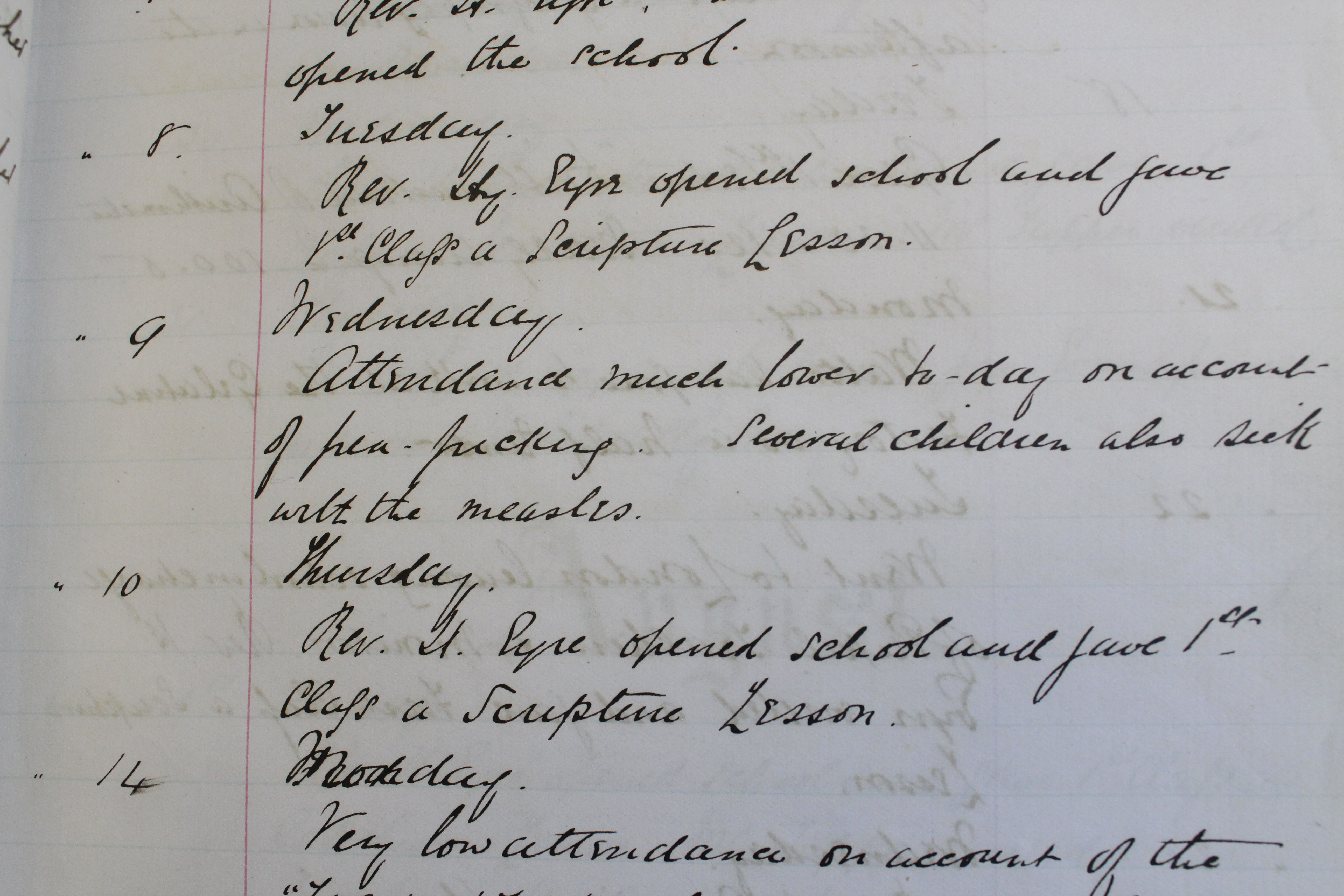

Or maybe you want to find out what people were eating in the early twentieth century. Try typing ‘meals’ and ‘sa’ in the search boxes. You should find oral history recordings that include memories of what the interviewees ate as children (bread, dripping, and fresh fruit and vegetables – acquired legally or otherwise – feature heavily). This clip from an interview with Rosemary Pitts of Great Waltham gives an example of what children ate in the 1920s-1930s (SA 55/4/1).

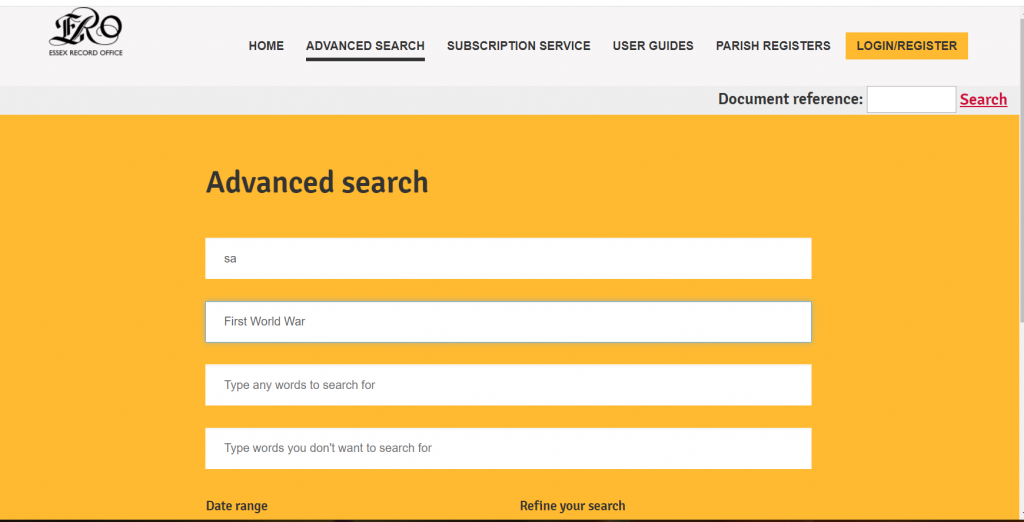

You can run an Advanced Search to better refine the results that you get. Click ‘Advanced Search’ at the top of the page. To search for a specific phrase, type this in the second box – and don’t forget to add ‘sa’ or ‘va’ to the top box. For example, try typing ‘sa’ in the top box and ‘First World War’ in the second box.

If you are searching for multiple words that might not appear as an exact phrase in the catalogue description, type your words into the top box. For example, if you are looking for information about Clacton Pier, this might be described as ‘Clacton-on-Sea Pier’, ‘Clacton Pier’, or ‘the Pier at Clacton’. To find all of these matches, type ‘Clacton’ and ‘pier’ in the top box – and add ‘sa’ or ‘va’ to the second box.

Tip: To search for sound and video recordings at the same time, type ‘sa’ and ‘va’ in the third box before clicking ‘SEARCH’.

You can also use our index search boxes from the ‘Advanced Search’ screen. Choose ‘People’, ‘Places’, or ‘Subjects’ from the ‘Refine your search’ box, and then type in the key words or names that interest you. This will only find results where your search term is a major part of the recording, and not just mentioned in passing. You will not be able to limit this search to just sound or video recordings, but if you sort the results by Reference, you can find the Reference Numbers that begin ‘SA’ or ‘VA’.

There are other finding aids that might help you locate relevant material. We have subject guides to sound and video recordings that cover: agriculture, Christmas, education, Essex dialect and accents, folk song and music, health, housing, shops and shopping, traditional English dance, transport, the First World War, and the Second World War. These are available in the Playback Room at the Essex Record Office, or from our website.

You can also read general user guides to Essex Archives Online on the catalogue: click ‘USER GUIDES’ at the top of the page.

Now that you can find material in the Archive, please come and listen! That is what it is here for. And do get in touch if you’re having trouble finding recordings. We would be happy to help.

But first here’s a little test for you to try. The result will be worth it, we promise.

- Click ‘Advanced Search’ from the top of the page.

- Make sure the ‘Refine your search’ box is set to ‘Everything’.

- In the top box, type ‘cucumber’ and ‘halstead’.

- In the second box, type ‘SA’.

- Click on the result.

- Enjoy.

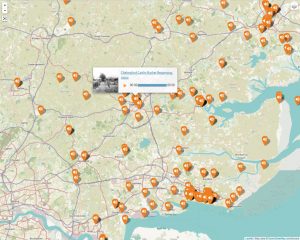

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.