To mark St George’s Day, Archivist Katharine Schofield takes a look at a very rare pen and ink decoration of George slaying the dragon on a manorial court roll from Great Waltham, dating from 1541.

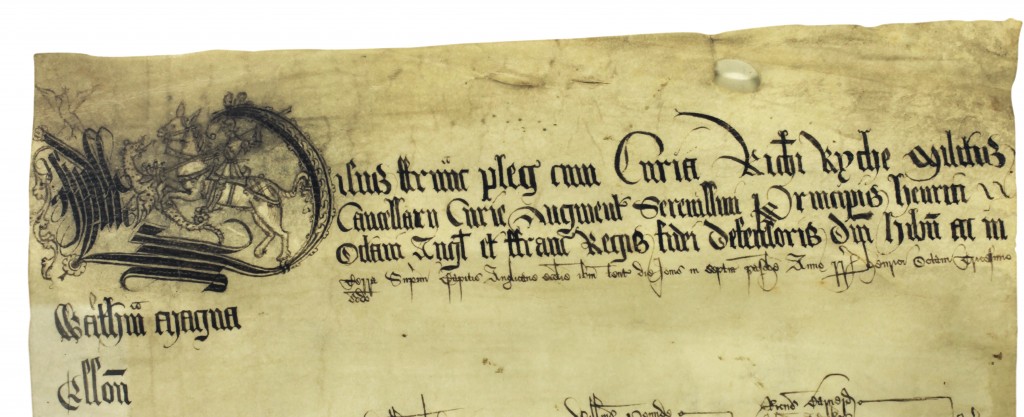

Extract from D/DHh M151, a manorial court roll of 1541 from Great Waltham, showing St George slaying the dragon

George and the dragon sit in the initial letter of the document. The words ‘Waltham Magna’ appear just beneath the decoration

Among the hundreds of manorial court rolls deposited in the Essex Record Office, a very small number have pen and ink decorations. These include a court roll for the manor of Great Waltham alias Waltham Bury (D/DHh M151) where the court for Easter 1541 has a drawing showing St. George slaying the dragon in the letter V (for visus or view, the view of frankpledge carried out twice a year in the court leet). The original is approximately 3.5 cm high and 7.5 cm across. The rolls were the working records of the court and not intended to be decorated so a ‘doodle’ as elaborate as this is a rarity.

Court rolls form the majority of the manorial records held in the Essex Record Office, which are held by Act of Parliament of 1924 under the authorisation of the Master of the Rolls. The Manorial Documents Register (MDR) was established two years later to record the location of the documents to ensure that they could be traced if they were required for legal evidence. The National Archives is in the process of computerising the Manorial Documents Register county by county and the work completed so far can be seen on the National Archives’ website here.

After more than two years of work the Essex contribution to the MDR is complete; you can find out more about the project and how you can use these fascinating documents at Essex through the ages on Saturday 12 July. (Details here.)

Manorial titles are not part of the MDR and records such as the letters patent of 1467, although relating to the rights of the lord of the manor, do not form part of the register. However, a search of Seax will locate this and many other ‘ancillary’ manorial documents, including deeds of sale of manors and also of copyhold premises.

By the later 15th century St. George’s Day was a well-established feast day in England. In June 1467 Edward IV granted Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex (his uncle by marriage), lord of the manor of Stansted in Halstead, the right to hold two three day fairs in the town, one of which was to take place on St. George’s Day and the two days either side (D/DVz 3). The other fair was to be held on the feast day of St. Edward the Confessor and the two adjoining days, 12-14 October. After the Reformation St. George’s Day was one of the saints’ days that continued to be celebrated in the Church of England and today churches throughout England will fly the flag of St. George on the feast day.

St. George was a soldier in the Roman army who became a Christian martyr. He came from a Greek Christian family and became one of the foremost military saints, venerated in the Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox churches. The flag of St. George is also used as the basis of the national flag of Georgia.

The adoption of St. George as the patron saint of England was a phenomenon of the Middle Ages. In 1222 the Synod of Oxford declared St. George’s Day (23 April) a feast day. At that date the most venerated saints in England were St. Edmund King and Martyr, whose shrine was at Bury St. Edmunds and St. [King] Edward the Confessor. This changed after 1348 when Edward III founded the Order of the Garter and associated St. George with the country’s highest order of chivalry. The chronicler Froissart recorded that English soldiers used St. George as a battle-cry at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 and throughout the Hundred Years War of the 14th and 15th centuries. Famously Shakespeare copied this in Henry V with Cry God for Harry, England and St. George!