March 2018 marks 200 years since the death of one of England’s most influential landscape gardeners, Humphry Repton. To mark this, we have chosen for March’s Document of the Month Repton’s ‘Red Book’ for Stansted Hall, commissioned in 1791 by William Heath (D/DQ 29/1).

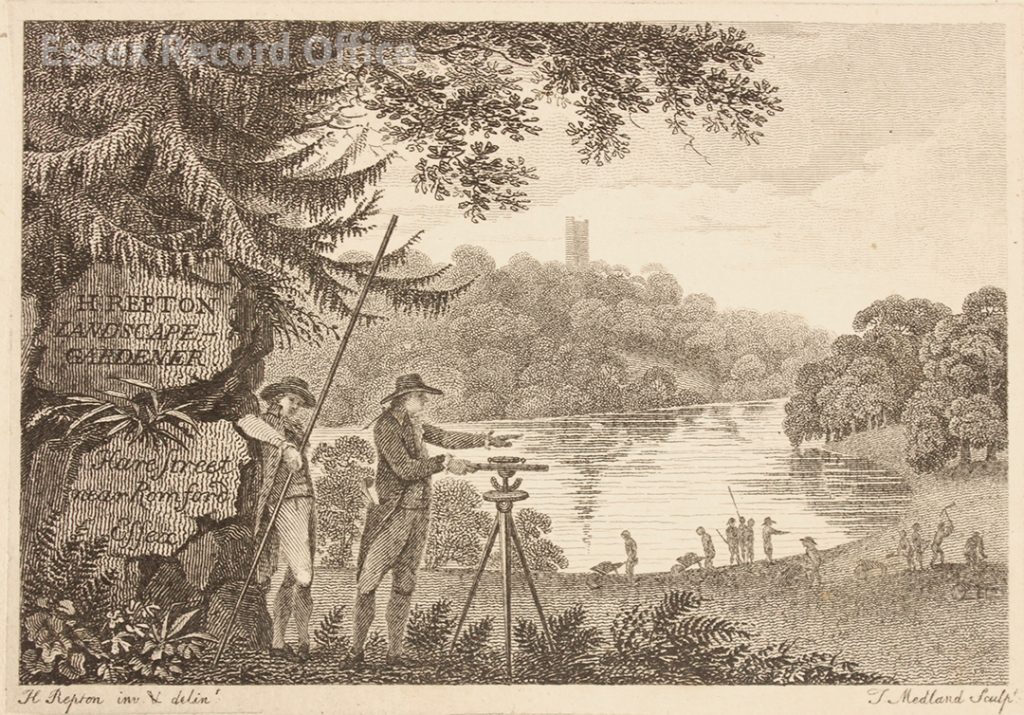

Repton worked as a design consultant, visiting his clients’ properties and making suggestions for how picturesque views might be created within the landscape. He is best known for his ‘Red Books’ – reports he created for his wealthy clients which outlined his suggested changes, bound in Morocco leather. These books include beautiful watercolour sketches with flaps that can be lifted to show the views before and after Repton’s proposals. The Red Books served a dual purpose; they showcased Repton’s ideas to his client, but they might also be shown to admiring friends and hopefully secure further commissions.

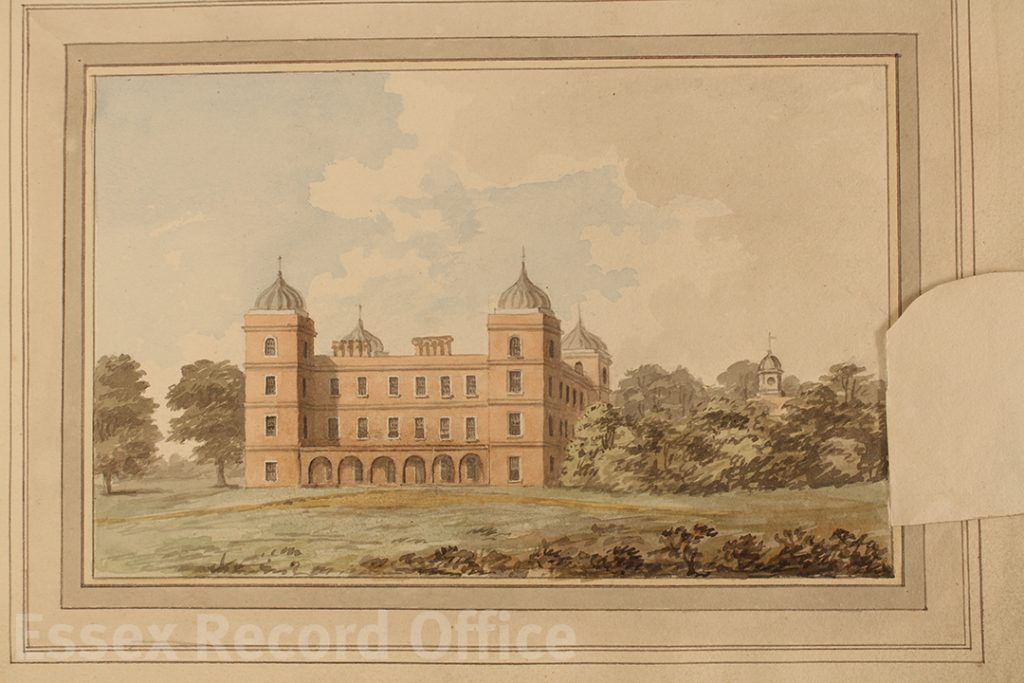

In the book for Stansted Hall Repton sets out suggestions for creating what he considered would be picturesque views from and towards the house. His first observation was that the house was rather sprawling, and suffered from an unbalanced appearance due to one of its four towers being shorter than the other three. He recommended that the house should not be extended any further, but that the smaller tower should be built up to match the others, and the sprawling buildings to the side be concealed with planting, allowing a cupola or clock turret to peek up above the trees.

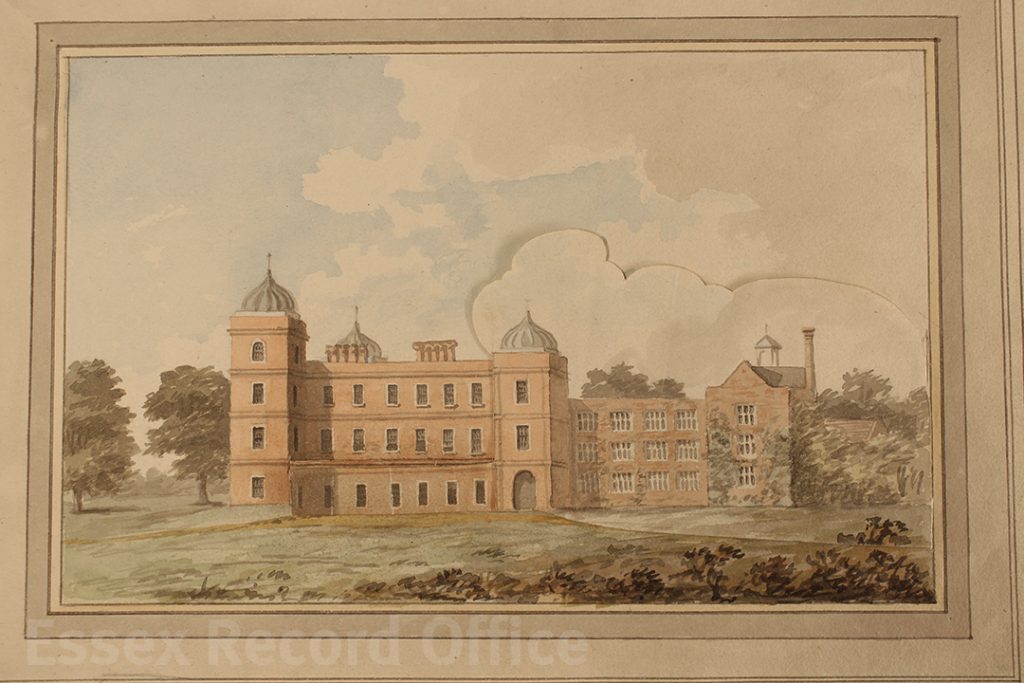

The Stansted Red Book includes one of Repton’s famous ‘lift the flap’ pages. With the flap down, we see a watercolour of the house as it stood.

A flap showing part of the existing view can be lifted…

…to reveal to the client the changes Repton was proposing. In this case, the building up of the shorter tower to match the others, and concealing part of the building with planting.

Repton also suggested covering the red brick building in a grey-white stucco wash, due to his ‘full conviction how much more important as well as picturesque a stone coloured building appears than one of red bricks … this alteration will [also] have a prodigiously pleasing effect from the turnpike road’.

Repton’s impression of what Stansted Hall would look like if rendered in white stucco, which he considered a vast improvement on its red brick exterior

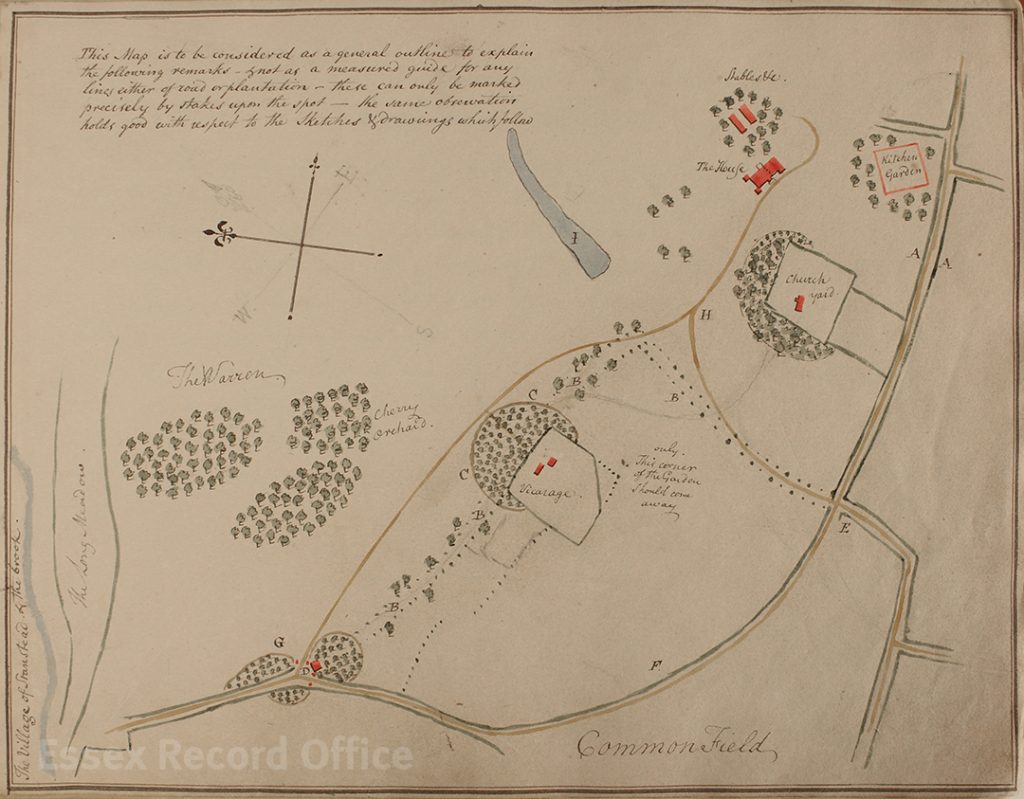

He also offered suggestions for creating an impression that everything within the views belonged to the estate, which meant concealing other buildings and public roads behind planting:

The park

I call the Lawn immediately surrounding a mansion by the name of Park, whether it supports deer or other stock. This sort of Park does not take its consequence from real extent, but from its supposed magnitude, and chiefly from its unity, or the appearance of all belonging to the same proprietor: high roads, hedges & houses belonging to other persons near the Mansion, always tend to lessen its importance, while plantations increase it.

To this end, Repton suggested concealing the vicarage which was near the hall with a plantation, and rerouting the approach road to carefully craft the views seen by visitors as they arrived.

Landscape gardening was not the career that had been intended for Repton. He was born in 1752 in Bury St Edmunds, the son of an excise collector. His parents had 11 children; Humphry was one of only 3 who survived infancy. He attended grammar school in Bury St Edmunds, and then in Norwich when his family moved there when Humphry was 10. Intended for a career as a merchant, at age 12 Repton was sent to live with a wealthy family in the Netherlands to learn Dutch and French. Returning to Norwich aged 16, he was apprenticed into the textile industry. He was, however, more talented in the arts than in trade, and was not a successful businessman.

In 1773 he married Mary Clarke, and having inherited some money he retired from business and set himself up in the north Norfolk countryside to live the life of a gentleman. After a few years, however, the money was running out. In 1786 Repton moved his family to Hare Street near Romford, and turned his skills at sketching and writing to a career as a landscape gardener.

His favourite commissions were from the established gentry and aristocracy, when sometimes he would be invited to stay at his clients’ grand houses. A large proportion of his work, however, was for villas of the nouveaux riches around London who had made their money in business and trade. By the end of his career, Repton believed he had prepared over 400 Red Books and reports, including for several properties in Essex.

In addition to his work for private clients, Repton also published treatises on the principles and practice of landscape gardening. These helped to secure his reputation and his influence on the field of landscape gardening.

Repton’s career had a rather sad end. Commissions became fewer and further between, something he blamed on the effects of the Napoleonic Wars, with new taxes and dramatic inflation reducing the amount of money the wealthy had to spend on luxuries such as landscaping.

In January 1811 the carriage he was travelling in returning from a ball overturned on an icy road and Repton sustained serious injuries from which he never fully recovered. He continued to work, visiting sites in his wheelchair, often in great pain. He died on 24 March 1818 at Hare Street, and is buried at Aylsham church in his beloved Norfolk.

The Stansted Hall Red Book will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout March 2018.

Thank you for sharing this information. I know Essex well as I lived in Barking for forty years before moving here to Aylsham where Repton chose to be buried. His older sister, Dorothy lived in a large house facing the Market Place. She had married a successful lawyer, John Adey. Humphry named his second child, who was born deaf, John Adey Repton. He was to become a well know architect, most famously known for his collaboration with his father, of Sheringham Park.

Thank you Geraldine, I’d wondered where his son’s name came from!