Chris Lambert, Archivist

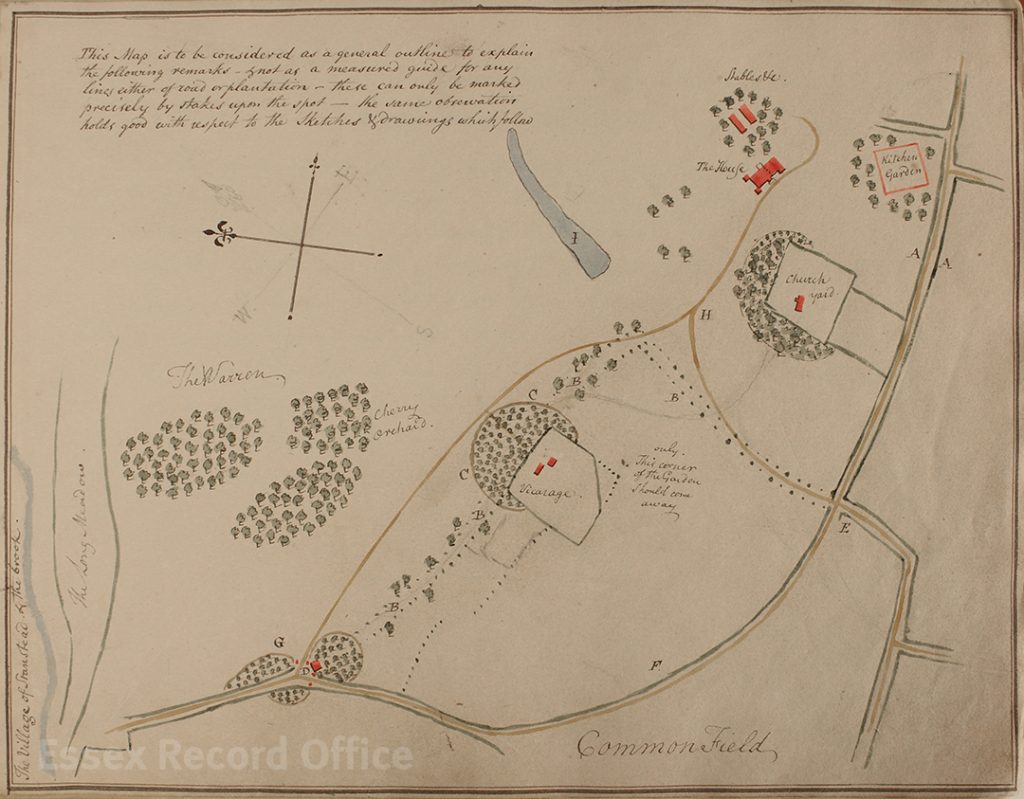

High summer, and thoughts perhaps turn to lazing in a garden. But for Robert Chatfield (born 1845), manufacturing chemist, gardening was to be taken seriously – as can be seen from this recently acquired record of his garden at Woodlands, Sewardstone, in the Lee Valley (D/DU 1510/6).

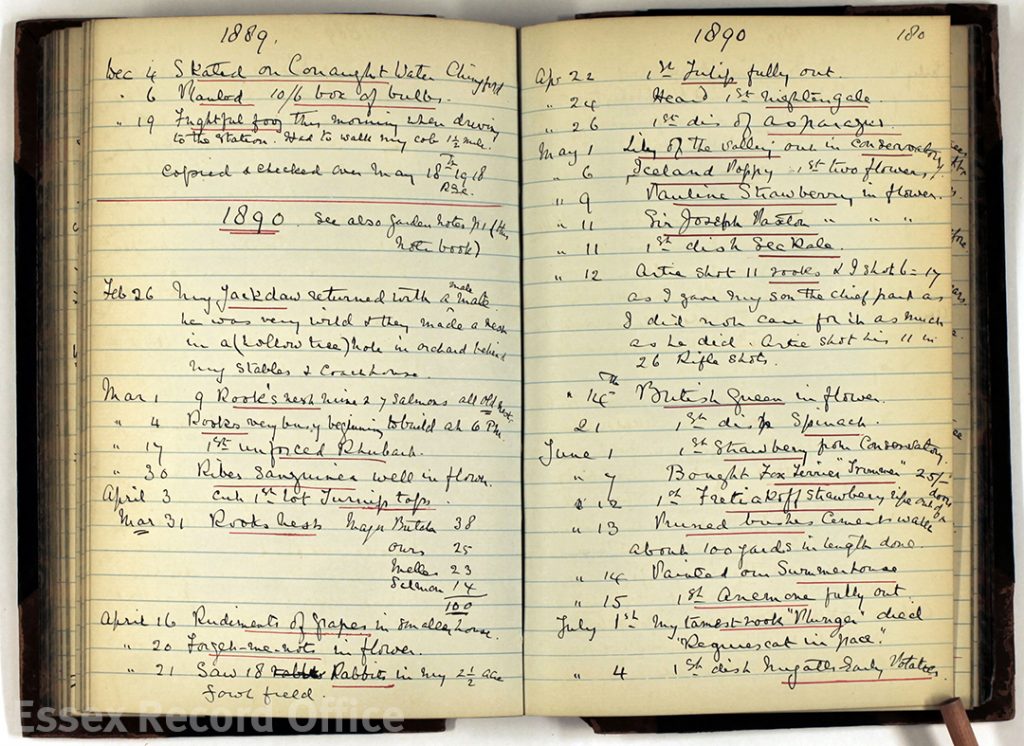

‘Country notes’ extracted by Chatfield in 1918 from his (lost) diary, illustrating the progress of the gardening year in 1890 and culminating in the first new potatoes on 4 July. Connaught Water, where he skated in December 1889, was a popular spot for recreation in Epping Forest.

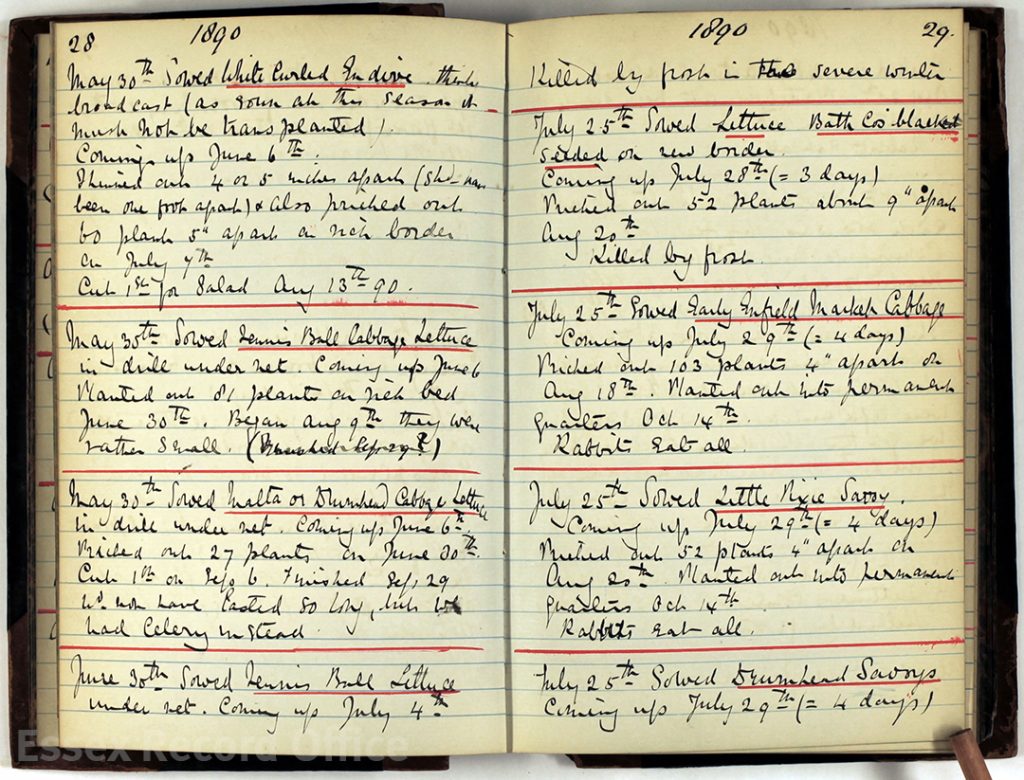

More detailed notes for part of the same period, describing the pleasures and sorrows of the kitchen garden.

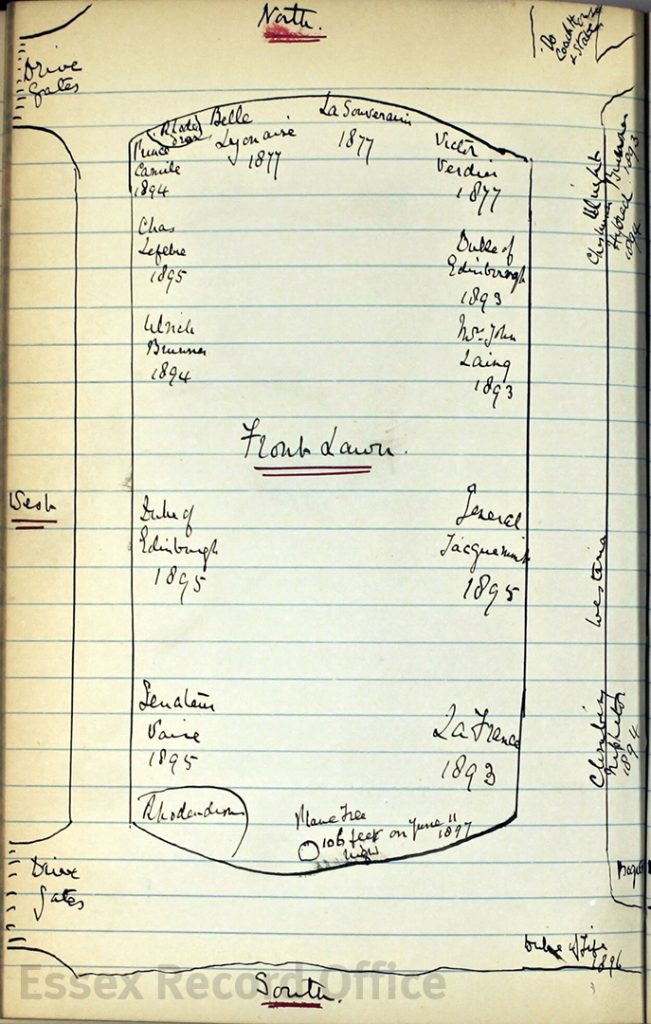

A plan of the front lawn at Woodlands, revealing a small initial planting of roses at one side of the drive in 1877, and a burst of additions in the 1890s.

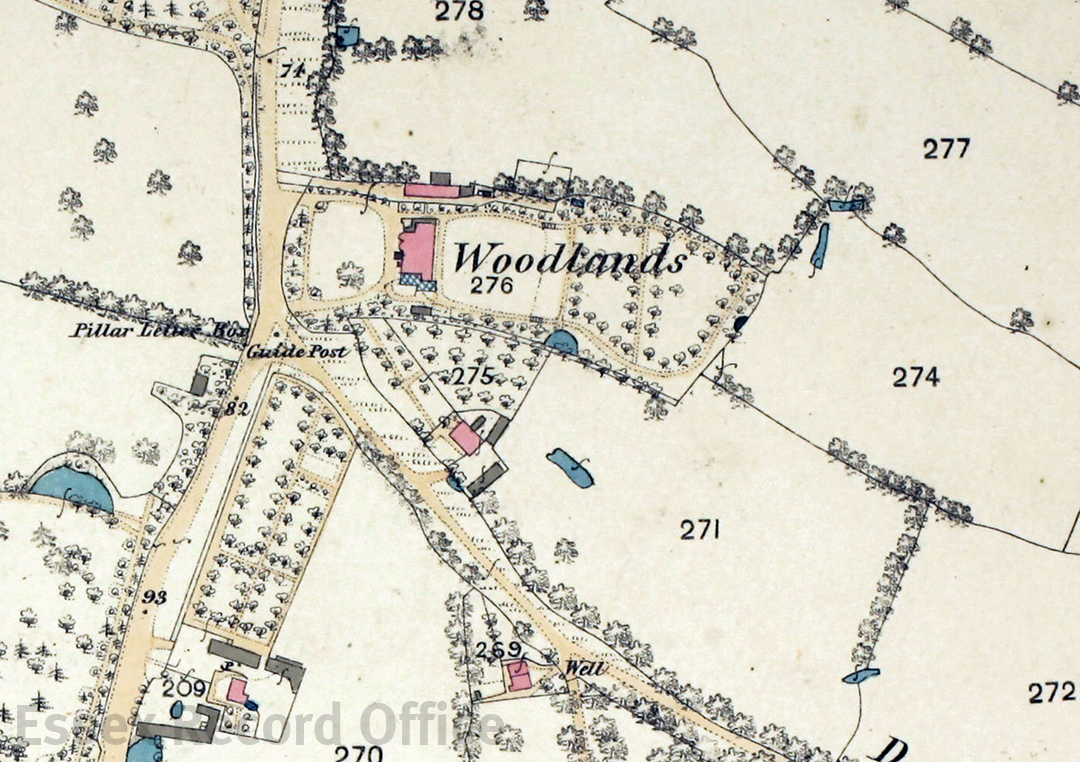

Chatfield took a 21-year lease of Woodlands in 1877, but his was not a local family. Robert was a Wiltshire vicar’s son; his wife came from Warwickshire; and their son Arthur had been born in north London. For professional people this corner of south-west Essex offered a degree of rural seclusion combined with fast rail links to London. Chingford station, opened in 1873, was only 2 miles away.

Woodlands in 1870, just before Chatfield took out his lease (Ordnance Survey 1:2,500 1st edition Essex 57.10)

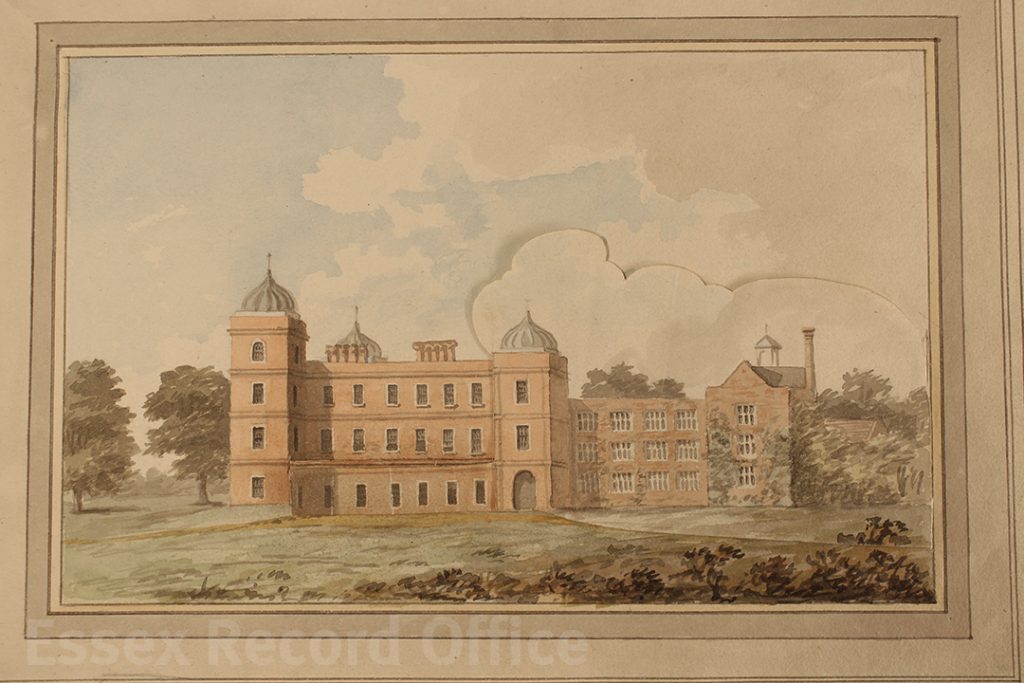

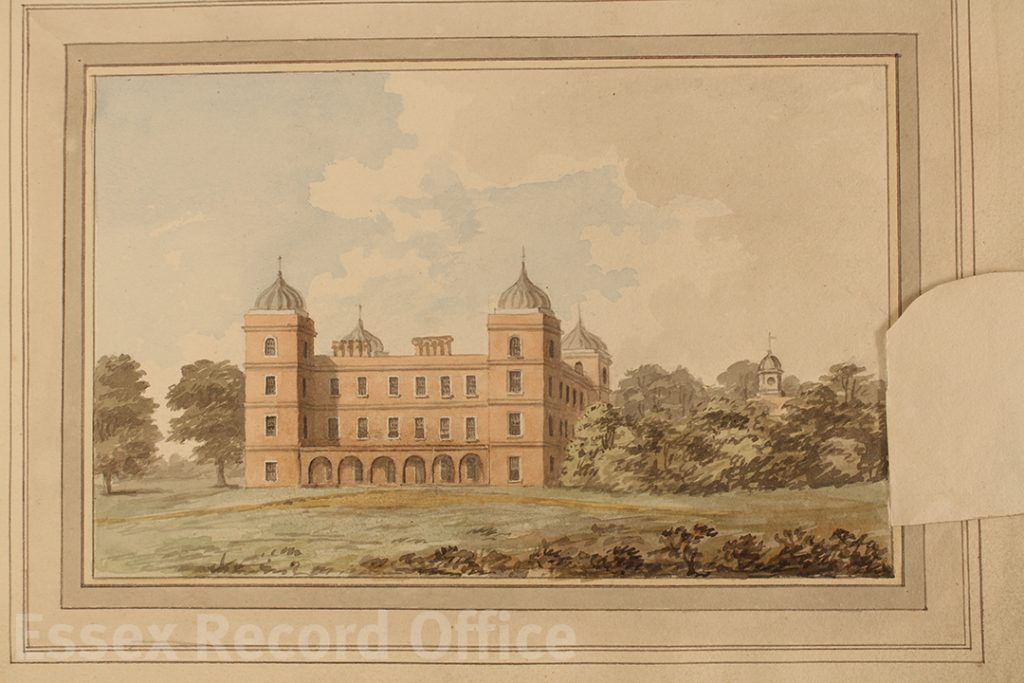

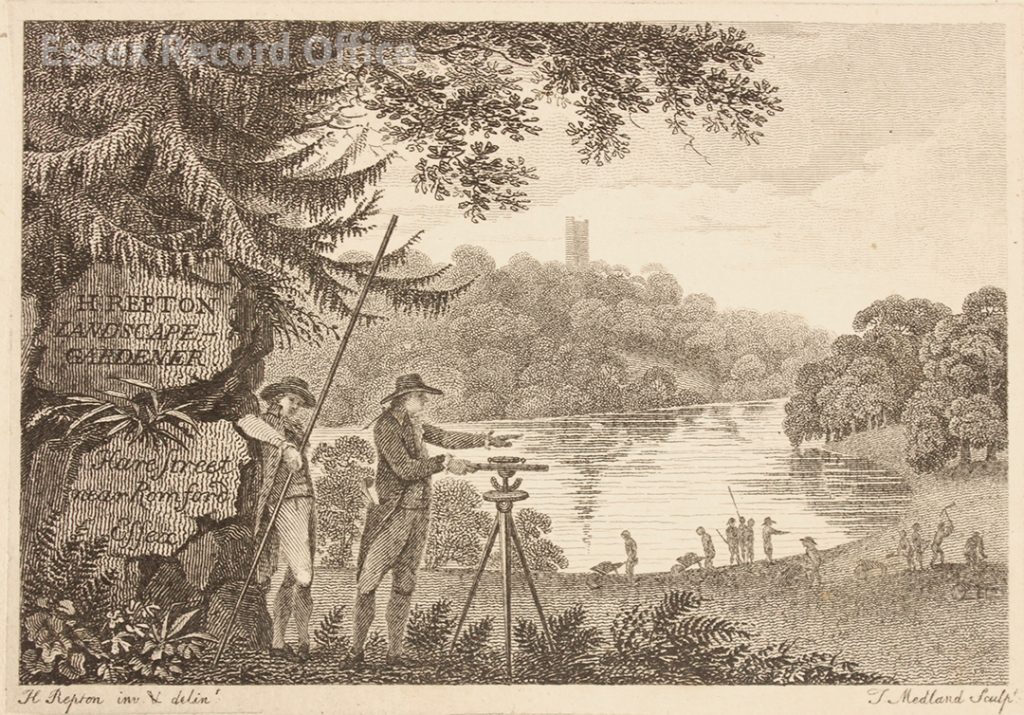

Woodlands was a brick and stucco villa, probably of the mid 19th century: not a grand pile, but not particularly modest either. Besides two female servants, Chatfield by 1889 employed an elderly local man, Richard Pearson, as a gardener to help him manage its 4 acres. Pearson was later joined or replaced by ‘Burgess’, but Chatfield rarely mentions either man in his notes. (His wife is not mentioned once: clearly the garden was a male undertaking.) He was punctilious in recording what he grew – or tried to grow – and especially the moments when flowers, fruit and vegetables were either planted or came into season, making this a valuable record of the gardening year. His careful naming of plants illustrates the wide choice of commercial varieties available to the late Victorian gardener.

Although a tenant, Chatfield also made considerable investment in the garden: in 1896 he re-laid the gravel drive, built a workshop for Arthur and provided the gardener with a toolshed. When their lease expired, just two years later in 1898, the Chatfields moved away. By 1901 they were living in rather more modest circumstances in Bowerdean Street in Fulham.

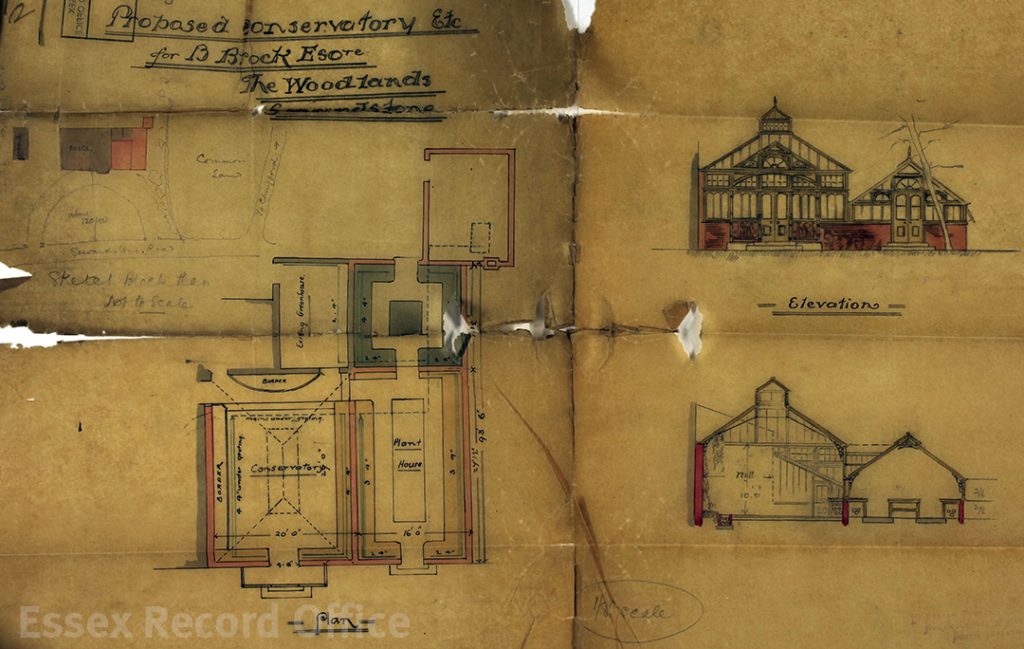

Woodlands itself seems to have had a few last years of prosperity: in 1901 the owner built a new conservatory on one end of the house.

The conservatory and ‘plant house’ built at Woodlands in 1901, after Chatfield’s departure (D/UWm Pb2/40)

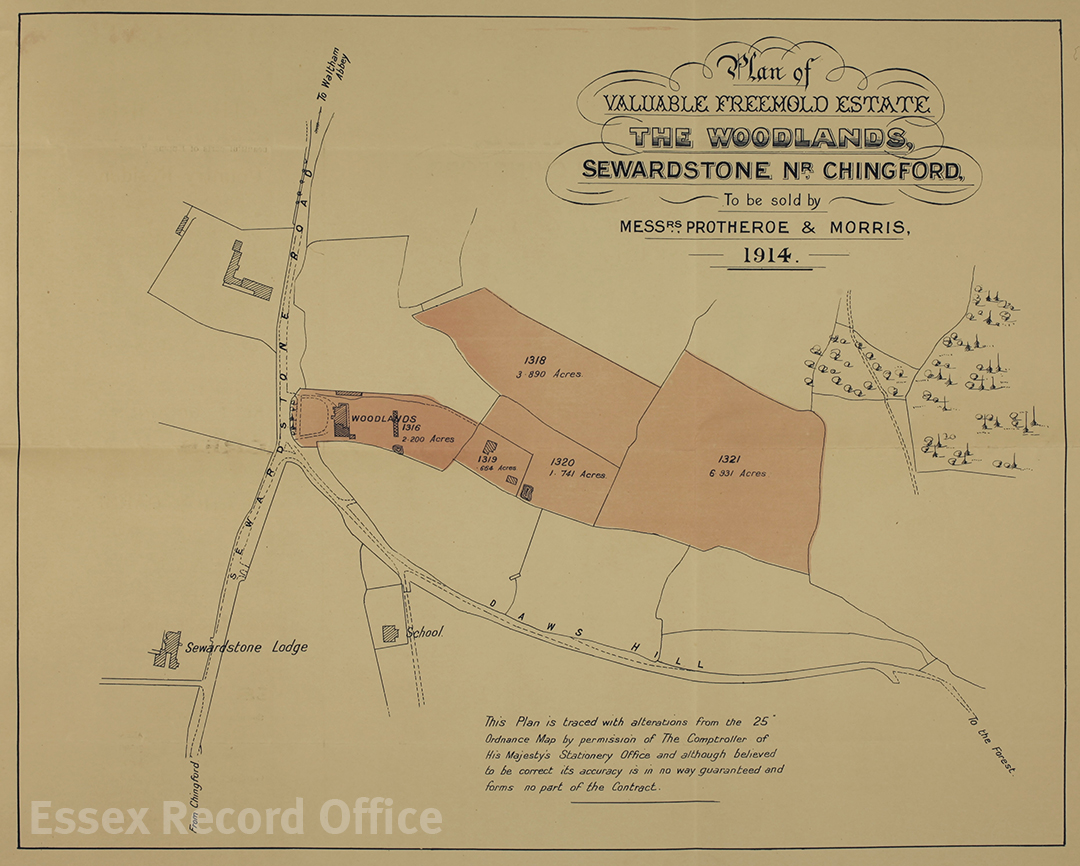

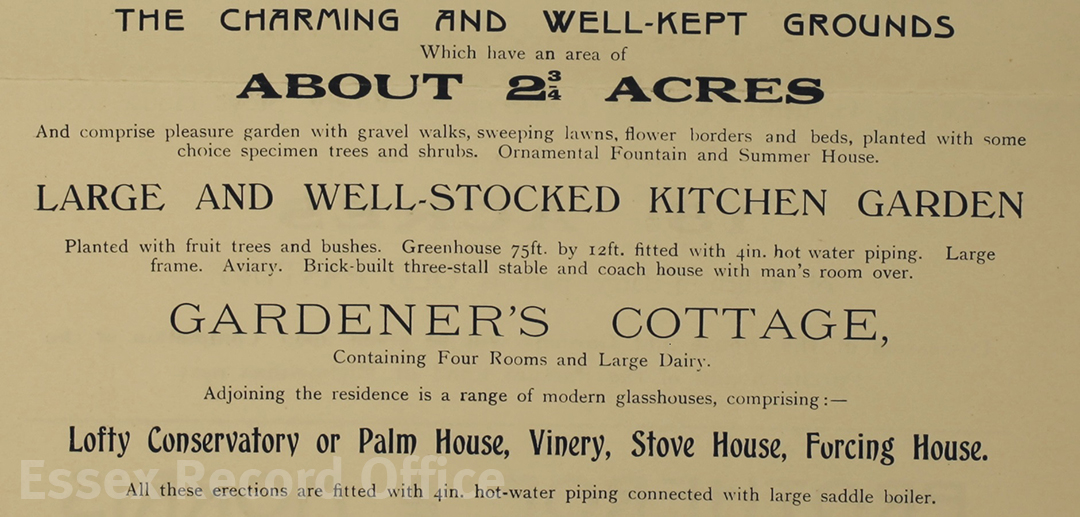

However, the area was changing quickly. From 1913 the meandering river was replaced by the George V Reservoir, fringed on the opposite bank by industrial development at Enfield. The Essex side became a centre of the Lee Valley glasshouse industry. Woodlands was put up for sale at least 3 times between 1914 and 1928, typically as an ‘old fashioned residence’.

The estate put up for sale in 1914 (SALE/A479)

The garden as described in 1914, with all the specialized structures that the serious gardener required (SALE/A479)

The last sale catalogue held by the ERO, dating from 1928, provides our only photographic record of the property, but ominously points to ‘land suitable for the erection of glasshouses’.

By 1935 house and, presumably, garden were gone. The Ordnance Survey map of that year shows nothing but a line of trees fronting the now empty plot, with an orchard to the rear – perhaps a last remnant of this English country garden.

Horticulture versus gardening: the site of Woodlands in 1935 (Ordnance Survey 1:2,500 Revision Essex 69.1)

Robert Chatfield’s garden notebook will be on display in the ERO Searchroom throughout July 2018.