On Wednesday 16 September 1908, Amy Hicks spoke at a suffrage meeting held at the Co-operative Hall in Colchester and declared that campaigners for women’s suffrage were ‘neither freaks nor frumps’.

This was the third of three suffrage campaign meetings that took place in Colchester that week, reported in the Essex Newsman on Saturday 19 September. The first meeting took place on Monday night in the High Street, where the speakers were ‘subjected to some humorous banter, and were “booed” by some small boys. The feeling was generally adverse to the Suffragettes’. When Miss Hicks spoke at the meeting on Tuesday night at St Mary’s school room, she said that the campaigners were ‘not at all disheartened by [this] noisy reception’.

By 1908 Amy Hicks already had a long background on the suffrage scene, having grown up with her mother, Lilian, campaigning for women’s voting rights. Lilian was born in 1853 in Colchester, to parents Edward and Thirza Smith. In a 1910 interview with The Vote, the magazine of the Women’s Freedom League, Lilian said that her father was ‘a great believer in women’s capability, and trained both his daughters to manage their own affairs and depend on their own judgment just as carefully and thoroughly as he trained his sons’.

Photographic postcard of Lilian Hicks issued by the Women’s Freedom League, c.1910 (from Yooniq images)

Lilian married Charles Thompson Hicks in Colchester in 1873, and in 1877 Amy Hicks was born. The family lived at Great Holland Hall, near Frinton-on-Sea. As their children grew up, Lilian became increasingly politically active. In 1884 both Lilian and Charles were involved in the campaign for votes for agricultural labourers. From the early 1880s, Lilian worked for the women’s suffrage movement, organising meetings across East Anglia.

Amy was academically gifted, and in 1895 went to Girton College in Cambridge to study Classics. She completed her degree course in 1895, being awarded a first class mark, and several academic prizes along the way (although Cambridge did not formally award degrees to women until 1948). For the next few years Amy taught in London, Liverpool, and briefly in Pennsylvania.

By 1902 both mother and daughter we members of the Central Society for Women’s Suffrage, and in late 1906 they joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by Emmeline Pankhurst. Their membership did not at this point last long, as they were part of a breakaway group in autumn 1907 that formed the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). The campaigners of the WFL were unhappy with how the WSPU was being run, and while they supported direct action and militancy they were not in favour of attacking people or property.

In the summer of 1908, Lilian travelled throughout Surrey, Sussex and East Anglia with fellow WFL member Margaret Wynne in the WFL caravan, making speeches to recruit people to the women’s suffrage cause.

The following year, 1909, Amy became secretary to the WFL, and was at the founding meeting of the Tax Resistance League. The argument of no taxation without representation was to remain one of Amy’s key campaigning points.

Women at a suffrage parade in c. 1908, holding a banner proclaiming ‘Taxation without representation is tyranny’. The fact that women had to pay tax but had no vote on how that tax money was spent was one of the cornerstones of the suffrage campaign (from the Women’s Library Collection Flickr page)

In July 1909 Amy was arrested and imprisoned for three weeks on charges of obstruction. The Times of 13 July described the scene that led to Amy’s arrest. Four members of the WFL had gone to Downing Street, which was an open thoroughfare at the time, to present a petition to the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. It was Amy who personally gave Asquith the petition when he arrived in a car outside number 10. Their defence counsel said that the four women had done ‘nothing but stand upon the pavement in a perfectly orderly manner’. Nonetheless, the magistrate imposed a fine of £3 or three weeks’ imprisonment; all four defendants chose the prison sentence.

Amy was arrested again, this time with her mother Lilian, on 18 November 1910 during the protest known as Black Friday, a struggle between suffrage campaigners and police in Parliament Square.

Photograph of the Black Friday protest on 18 November 1910. The woman on the ground is Ada Wright. The building in the background is the Houses of Parliament. The WSPU sent a delegation of around 300 women to protest the actions of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith in not allowing more time for a women’s suffrage bill that had been under discussion in parliament. About 200 of the women were assaulted as they attempted to reach the Houses of Parliament. 119 women and men were arrested.

Their experiences between 1907 and 1910-11 must have hardened Amy and Lilian to the WSPU’s more militant methods of protest, for Amy rejoined in 1910 and Lilian in 1911. In 1911 both women took part in the census boycott co-ordinated by suffrage campaigns.

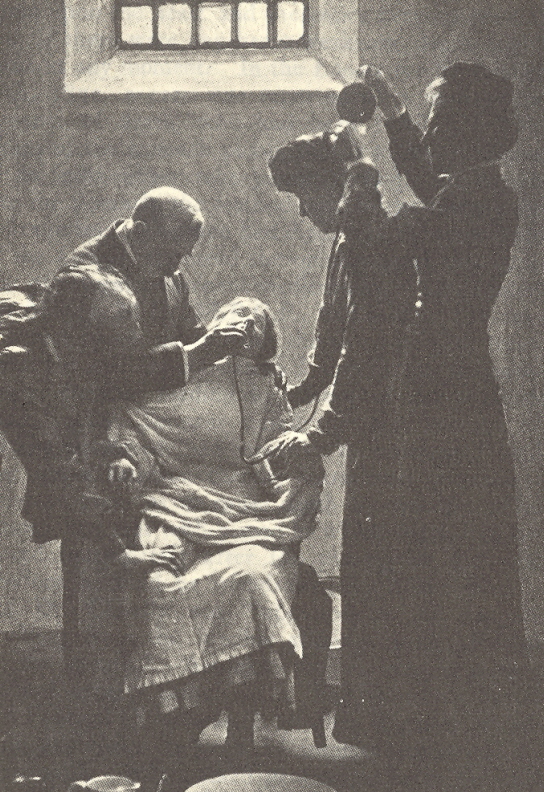

In March 1912, Amy was imprisoned again, this time for four months for taking part in the WSPU window-smashing campaign in London’s West End. She spent time in both Holloway and Aylesbury, including a period in solitary confinement. The Home Office considered her to be one of the ring leaders of the hunger strike at Aylesbury, and along with her fellow campaigners, Amy was subjected to the brutal procedure of forcible feeding.

Illustration of a suffragette being forcibly fed in HM Prison Holloway. Prisoners were forcibly restrained, and a rubber tube inserted into their mouth and down to their stomach. Emmeline Pankhurst, founder of the WSPU, described her horror at the screams of the women being force-fed in Holloway prison.

After her release from prison Amy was back out campaigning. The Walsall Advertiser of 7 December 1912 records a speech she gave as a guest at the Walsall branch of the WSPU, in which she talked about how peaceable approaches to the government had not worked:

‘Miss Hicks, in the course of her address, said that women had found out that mere words did not carry them very far, and they now said to the Government, “You may take our goods, and sell them, you may take our bodies and put them into prison, but money, to keep up your unconstitutional government, you shall not have.” She thought that was a very good method, and she hoped it would be carried out more widely and would create a great deal of embarrassment for the present Government. Considering the way in which the Government had treated women the best thing the women could do was to embarrass them in every possible way. There was too much feeling that the women did not count, and they were not looked upon as responsible members of society, as they ought to be, especially in matters of the State. They had found that any amount of talking was useless, and that was why they took more drastic measures to get those things altered… The women could not trust their interests in the hands of a body of men who were not responsible to them.’

During the First World War Amy joined the Women’s Volunteer Reserve, which was founded by Suffragette Evelina Haverfield. Her brother Charles, a solicitor, joined in army in September 1914 and was sent to France in 1916. He survived until 21 July 1918 when he was killed in action near Hazebrouck.

The Representation of the People Act gave the right to vote to all men aged over 21, and to women over 30 who met a property qualification. Equal voting rights – for all men and women over 21 – were not granted until 1928.

From the 1920s Amy lived at Runsell Green in Danbury, and her mother joined her there. Lilian died in 1924.

In 1927, in her fiftieth year, Amy married John Major Bull, a widower twenty years her senior. In the same year Amy was elected as a rural district councillor in Chelmsford, a position she fulfilled until 1930. Amy was widowed in 1944, and sometime before 1948 was awarded an MBE. After John’s death she lived at General’s Orchard in Little Baddow, until her death in 1953.