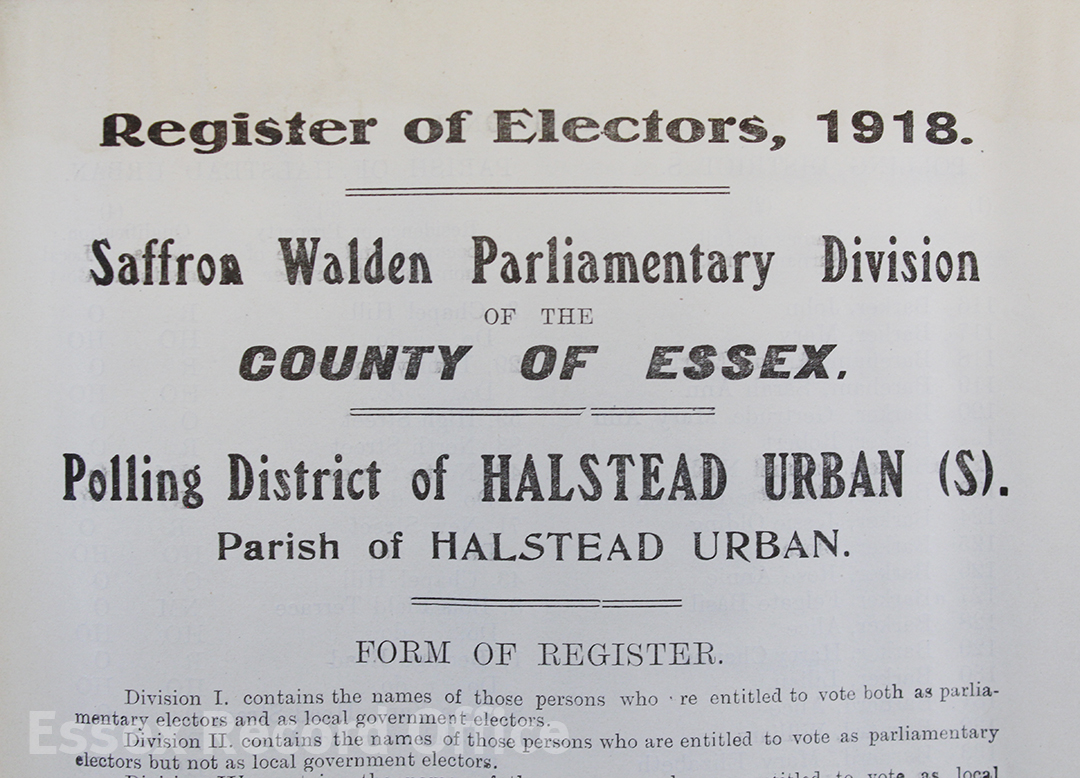

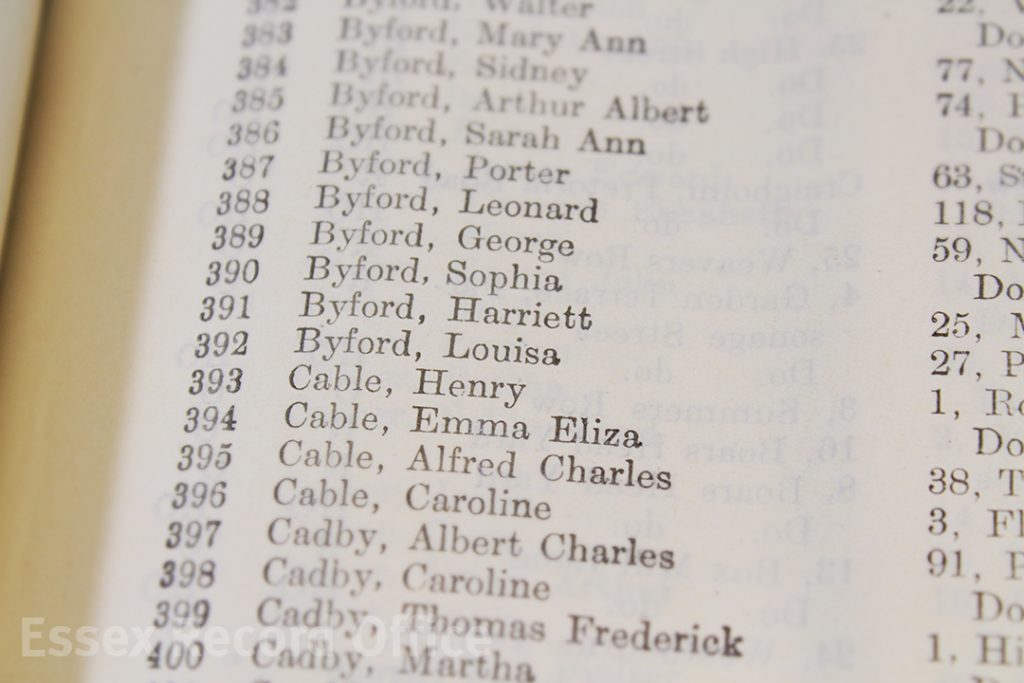

To celebrate International Women’s Day 2018, in the centenary year of some British women getting the parliamentary vote for the first time, we have been finding out about sisters Dorothea and Madeleine Rock of Ingatestone, who both spent time in prison for their part in the campaign for votes for women.

Dorothea and Madeleine were daughters of Edward Rock, an East India tea merchant, and his wife Isabella. They were born in Buckhurst Hill, Dorothea in 1881 and Madeleine in 1884, but by 1891 the family had moved to Station Lane in Ingatestone. The sisters had a middle class upbringing, with a governess, a cook, and a housemaid all employed in the household.

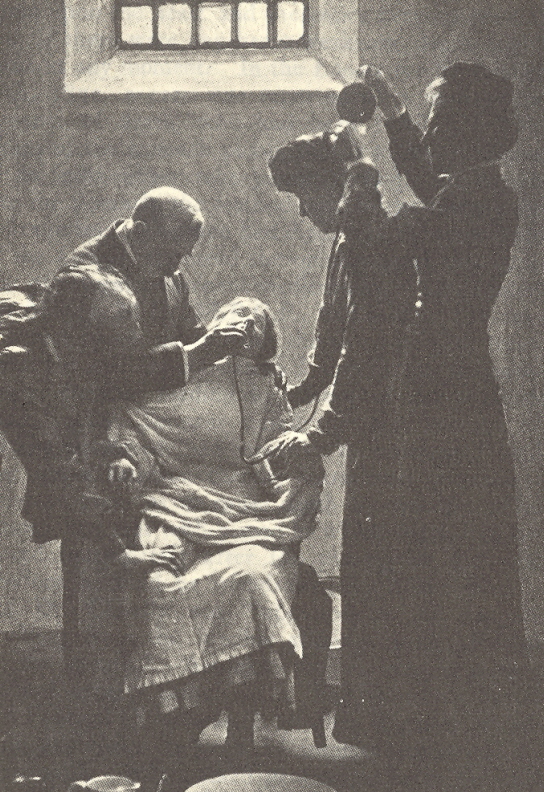

Sisters Dorothea and Madeline Rock of Ingatestone, left and centre. The caption on the back of the photograph does not tell us which sister is which, or the identity of the third woman, although she may be their governess, Louisa Watkins. This photograph has been digitally restored. (T/P 193/13)

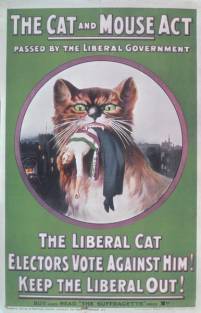

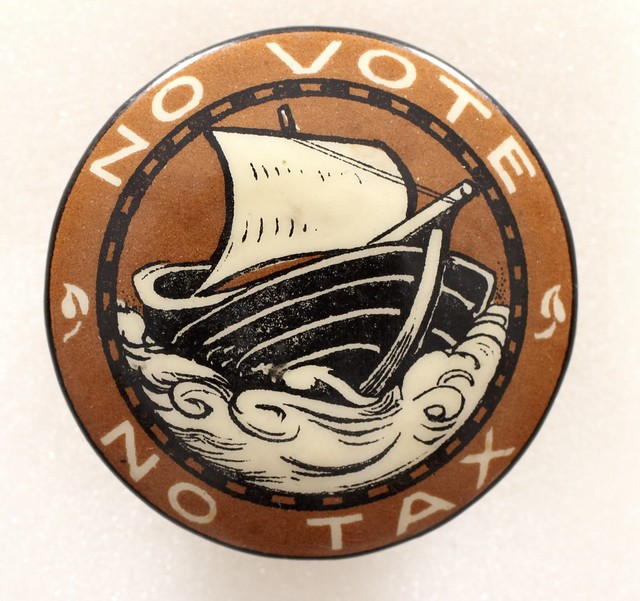

In 1908 both joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a militant organisation led by Emmeline Pankhurst. After decades of petitioning and lobbying with little result, the WSPU approach was ‘Deeds not Words’. Their tactics included smashing windows of government buildings and upmarket shops, setting fire to letter boxes, vandalising golf courses, and in extreme cases arson of unoccupied buildings.

We can track some of the WSPU activities of the Rock sisters by searching local newspapers (this is made so much easier and faster by accessing the newspapers through the British Newspaper Archive online, which allows you to search for key words. You can use the BNA for free at ERO and Essex Libraries).

The first mention of the Rock sisters’ WSPU activities that I have found so far is in the Essex Newsman of 13 March 1909. A short piece in the local news columns descibes a rummage sale held at the Rock residence, the Red House, to raise funds for the WSPU.

On Monday 6 September 1910, Madeleine presdied over an open-air meeting in the market square at Ingatestone, where, the Chelmsford Chronicle (9 September) reported, ‘There was a good attendance’. The meeting was given a ‘spirited address’ by a Miss Ainsworth. A few weeks later (reported in the Essex Newsman, 29 October 1910), Dorothea spoke on votes for women at the Ingatestone Debating Society; the meeting passed a resolution in favour of the Conciliation Bill then going through parliament which would have given some women the vote (the Bill was later defeated).

The first time the local papers mention the sisters being arrested is in late 1910. From the Chelmsford Chronicle of 25 November 1910 we learn that the Rock sisters had been arrested for taking part in a raid on the House of Commons, along with other Essex suffragettes:

Essex Suffragettes Raid

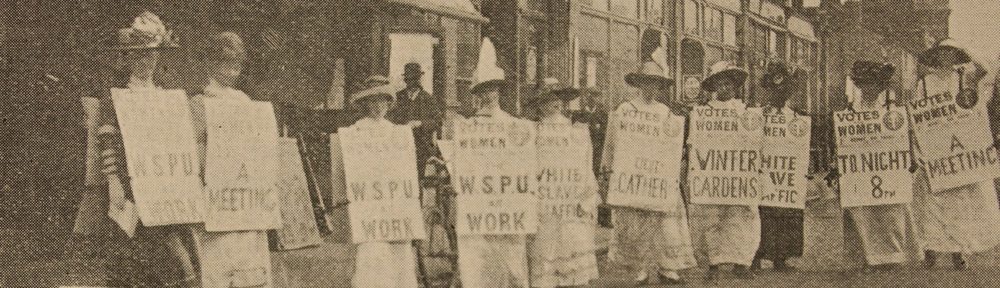

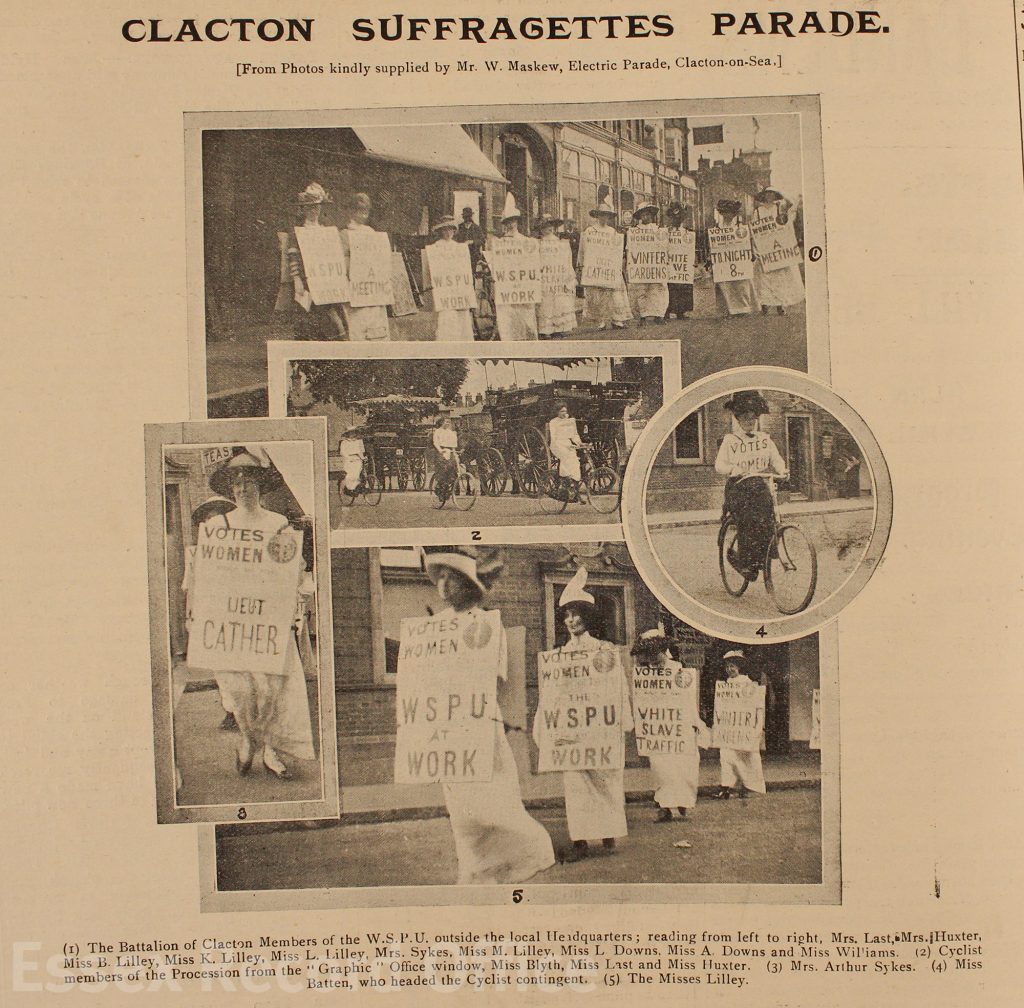

Among the 116 ladies arrested during the raid of the suffragettes on the House of Commons on Friday were the Misses K. and L. Lilley, of Clacton-on-Sea; Madeline Rock and Dorothea Rock, of Ingatestone; and Mrs Emily K. Marshall, of Theydon Bois, a daughter of Canon Jacques… The defendants surrendered to their bail at Bow-street, on Saturday, when Mr. Muskett, under instructions from the Home Secretary, withdrew from the prosecutions, and the whole of the ladies were discharged. The suffragettes regard the action of the authorities as a great triumph for the cause.

Chelmsford Chronicle, 25 November 1910

In April 1911, the sisters joined in with the boycott of the census. Instead of completing the household return with details of the occupiers, Dorothea filled the page with a message:

I, Dorothea Rock, in the absence of the male occupier, refuse to fill up this census page as, in the eyes of the law, women do not count, neither shall they be counted

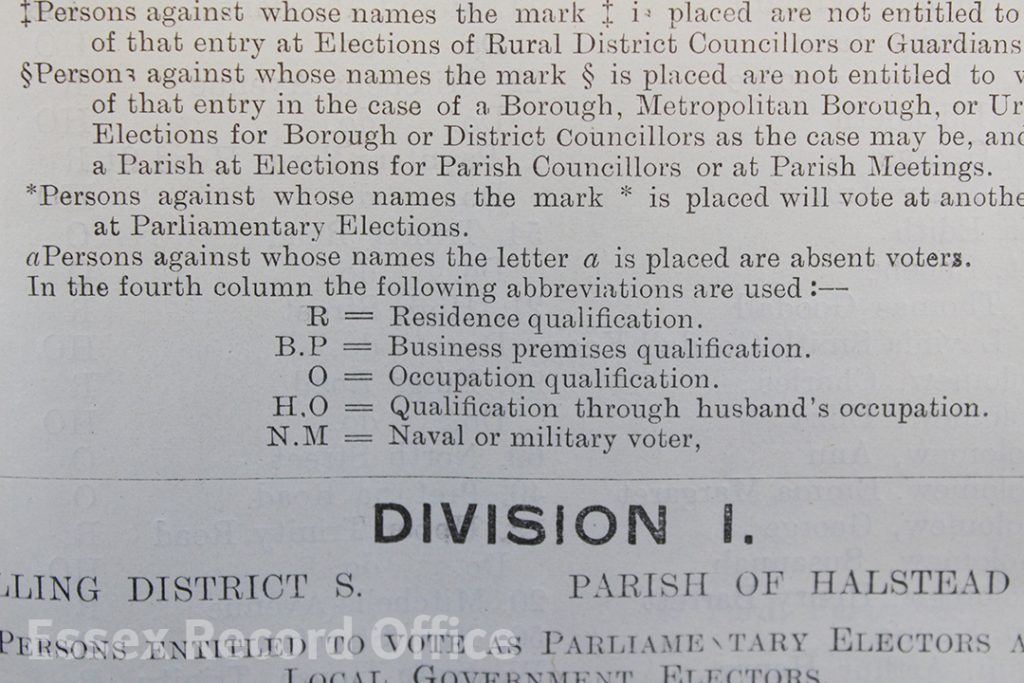

The enumerator later added some details of the people who lived there – Mrs Rock, 55, Dorothea Rock, 27, described as a ‘News vendor’ (presumably distributing copies of the WSPU paper), and Madeleine, 25, along with three unnamed servants. (If Dorothea had known doubtless she would have been annoyed.)

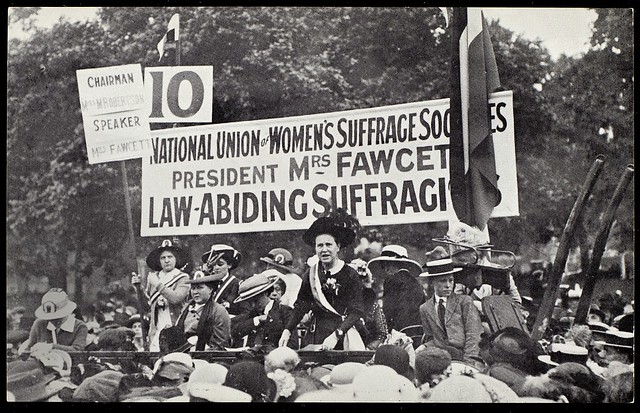

Not everyone agreed that the census boycott was a good idea. A few days before the census was held, there was a meeting of the Chelmsford branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) at Shire Hall (reported in the Chelmsford Chronicle on Friday 31 March 1911). The meeting was addressed by Miss K.D. Courtney, honorary secretary of the National Union, who described the census boycott as ‘futile and a waste of time’. A Miss Rock (the Chronicle doesn’t specify which one) defended the boycott, saying it aimed ‘to show the Government how many women there were who would submit no longer to being treated as mere chattels’.

The sisters again took militant action in November 1911. The Chelmsford Chronicle reported:

Suffragette riot in London

Essex women arrested

A serious riot was the result of Tuesday’s demonstration by the militant section of Suffragettes in London. The women essayed to approach the House of Commons with a view to some of their number entering the House. A strong cordon of police, however, prevented the women from carrying out their object. Many disgraceful scenes took place, and 223 arrests were made. Organised bands of women appeared in different parts of the West End, breaking windows with hammers and stones, the damage being estimated at hundreds of pounds. Among those arrested were the following Essex women: – Grace Cappelow [sic], Hatfield Peverel; Marie Moore, Forest Gate; Emily Catherine Marshall, Theydon Bois; Constance Nugent, Leytonstone; Dorothy [sic] Rock, Ingatestone, Madeline Rock, Ingatestone; and Sybil Smith, Chigwell.

Chelmsford Chronicle, 24 November 1911

Madeleine at least was sentenced to a week in prison; her release was reported in the Chronicle of 1 December 1911.

The next mention I’ve found of the Rock sisters in the Chelmsford Chronicle is 23 February 1912, when Dorothea spoke at a suffrage meeting in Chelmsford:

The Suffragettes have held several successful meetings in the open air, and on Wednesday a well-attended drawing-room meeting was held at Yverdon, London Road, the residence of Alderman and Mrs. Maskell. The expected speaker, Miss Wylie, was called away to work in the Glasgow Bye-election, so Miss Dorothea Rock took her place, with Miss Grace Blyth in the chair. In the evening there was a meeting for shop assistants. Miss Chapelow [sic] recited “The Song of the Shirt,” and Miss Rock again spoke.

Chelmsford Chronicle, 23 February 1912

A few short weeks later the Rock sisters were back in London, smashing windows at Mansion House with hammers and stones. This incident led to the longest Chelmsford Chronicle article that I have come across about the Rocks:

This newspaper column was preserved along with the photograph of the sisters posted above (T/P 193/13)

At the Mansion House on Tuesday, four Suffragists – Dorothea Rock, 30, and Madelaine Rock, 27, both giving addresses at the Red House, Ingatestone, the former described as of no occupation and the latter as a poet; Grace Chappelow, 28, The Villa, Hatfield Peverel, no occupation; and Fanny Pease, 33, of 4 Clements’s Inn, hospital nurse – were charged before Sir George Woodman with wilfully breaking windows at Mansion House.

The cases of Dorothea Rock and Grace Chappelow were taken first, and a constable said that about 10.15 on the previous evening he saw the two defendants walk up to the kitchen window of the Mansion House, in Walbrook, and deilberately break eight panes of glass with two hammers and stones. He arrested them, and at the statino a hammer and two stones were found on Rock and three stones on Chappelow, whose hammer had been left on the window sill.

Evidence having been given that the damage done was to the value of £2, Chappelow said she thought that was rather a high estimate.

Dorothea Rock: This thing is not done as wanton damage – we have done it as a protest against being deprived of the vote.

The Alderman: But it was wanton damage, whatever you may call it. Are you Londoners?

Rock: no, we have come up from Essex.

The Alderman: For this little prank. (Laughter.)

Rock: No, to do our duty… We selected the Mansion House because of the insult offered to our women here the other day by the Lord Mayor ordering them to be ejected from a meeting here.

The Alderman: I cannot find any excuse for treating you leniently or differently from other people. You are either criminals or lunatics, one of the other, and you will each have two months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

In the case of the other prisoners, Madelaine Rock and Fanny Pease, evidence was given by P.c. Washer that he recognised Rock as a seller of the “Votes for Women” paper in the vicinity of the Mansion House. He saw her throw a hammer enclosed in a glove at one of the windows of the basement of the Mansion House, but the weapon rebounded off the iron protections. The other prisoner was with her, and three two stones at the window.

Rock: It was my stone with broke it.

Both prisoners made statements in their defence on the lines of the previous two women.

The Alderman said he was sorry to punish these women in this way, but they were acting under an entirely mistaken view of their case. They were violent as agaisnt the public, and that was bound to bring punishment in its train. He must punish them equally as he would do a poor wandering man in the street who broke windows, and they must go to prison for two months with hard labour.

Pease: We are not afraid.

The Alderman: I can’t talk to you. You must remember that you are dealing with Englishmen, who are not to be driven to do that which they will not do of their own free will.

Interested spectators of the proceedings were the Lord Mayor and the Lady Mayoress, who were seated in the counsel’s seats.

So began two months in Holloway prison for the Rock sisters, along with several other fellow Suffragettes arrested in the March window smashing campaign. Many of the Suffragette prisoners went on hunger strike as a protest, and the prison authories responded by forcibly feeding them. This involved restraining the woman and pushing a rubber feeding tube through their nose or mouth into their stomach. Emmeline Pankhurst, in her book My Own Story, wrote that ‘Holloway became a place of horror and torment… I shall never while I live forget the suffering I experienced during the days when those cries were ringing in my ears’.

The Rocks appear in the volume of poetry published by the imprisoned campaigners, Holloway Jingles. Madeleine is described in some documents as a poet, and one of her poems was included in the book (you can read more about this in this preview of Glenda Norquay’s book Votes and Voices). Dorothea, meanwhile, is believed to be the subject of a poem, “To D.R.”, written by Joan Baillie Guthrie under the pseudonym Laura Grey.

While in Holloway Dorothea met Zoe Procter, who was to become her lifelong partner. Zoe had become involved in the WSPU in 1911 when her sister took her to a meeting, and she joined the Chelsea branch, running the lending library. An impassioned speech by Christabel Pankhurst inspired Zoe to take part in the window smashing campaign on 1 March that year, and armed with a hammer concealed in a large muff she smashed her window, and was sentenced to six weeks in Holloway.

However unpleasant their experience in Holloway, the Rock sisters were undeterred from pursuing further militant activitie. In July 1913 Madeleine was arrested for allegedly attempting to protect Sylvia Pankhurst from arrest:

INGATESTONE SUFFRAGIST ARRESTED.

“TOOLS OF THIS TYRANNY.”

Among the persons arrested at the Suffragist gathering at the Pavilion on Monday, and who appeared before Mr. Denman at Marlborough Street in Tuesday on charges of obstruction and assault, was Madeleine Rock, 30, described as a poet, of Ingatestone.

Inspector Riley stated that after he had arrested Mrs. Pankhurst the defendant, with two others, attempted to prevent him leaving the theatre with her.

Defendant Rock said she did nothing, but she felt Sergt. Cox’s stick. It came down on her head when she was not doing anything.

One of the defendants, Francesca Graham, was discharged.

Mr. Denman said the other two defendants must enter into recognisances to keep the peace for six months.

Miss Rock: I will not keep the peace; how long will you be the tools of tyranny?

Mr. Denman said if defendants were not willing to be bound over they must find two sureties in £20 each, or in default go to prison for twenty-one days.

Eventually the defendants found sureties.

Chelmsford Chronicle, Friday 25 July 1913

With the outbreak of the First World War in the following year, most militant campaigning activity ceased.

Madeleine continued to write poetry and published two volumes of her work, Or in the Grass in 1914 and On the Tree Top in 1927. She lived until 1954, leaving the residue of her estate to Marjorie Potbury, her cousin and a fellow suffragette.

Dorothea lived with Zoe Procter at 81 Beaufort Mansions, Chelsea, and Shepherds Corner, Beaconsfield. She wrote plays, in some of which Zoe performed. Zoe died in 1962 aged 94, leaving a substantial estate to Dorothea. Dorothea herself died in 1964, leaving bequests to Grace Chappelow and to Marjorie Potbury.