Earlier in the year we published a list of useful resources for those researching aspects of the First World War, which you can find here. There are new resources appearing all the time, so we thought we would share some more with you.

The British Library

The British Library have recently launched their fantastic First World War web pages, using which you can explore over 500 historical sources from across Europe, together with new insights from First World War experts. The web pages include nearly 500 historical sources from both sides of the conflict, contributed by institutions from across Europe, specially commissioned articles from historians, and resources for teachers. The pages cover a huge range of different themes, from the origins of the war, to the lives of soldiers, to propaganda, to historical debates.

You can find the World War One resource here:

http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one

The National Archives

The National Archives hold the official UK government records of the First World War, including a vast collection of letters, diaries, maps and photographs. You can explore these collections and advice on how to use them on TNA’s First World War web pages. You will also find details of their extensive programme of events marking the centenary.

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/first-world-war/

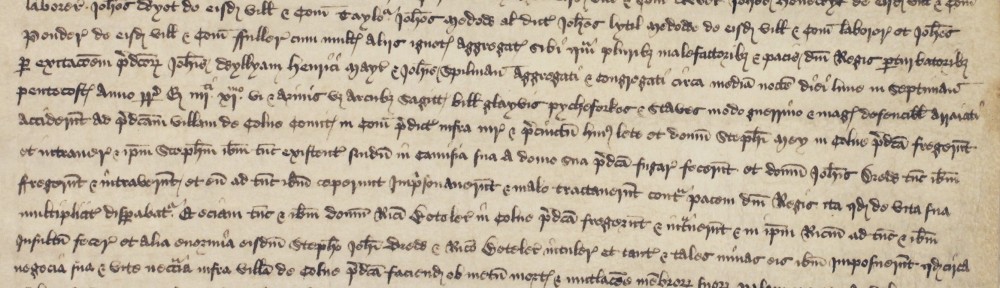

Middlesex military service appeal tribunal records, 1916-1918

The National Archives have recently digitised the records of the Middlesex military tribunal appeals from 1916-1918. When conscription was introduced in 1916, men could apply to a local military tribunal for exemption, and could appeal against a local decision to the county appeal tribunal. They often include supporting letters written by family arguing why their son, brother or husband should not be called up.

The tribunal heard over 11,000 cases, most of which were rejected outright. Only 26 men succeeded in being completely exempted from being called up. Only 577 of the cases the Middlesex tribunal heard were conscientious objection cases (just over 5%), and most of them were rejected.

The Middlesex records are rare survivors; at the end of the war, the government ordered the destruction of the tribunal records due to the sensitive material they contained. Only the Middlesex records and a set in Scotland were kept as representative samples.

The records have been difficult to access, but are now searchable by name, place, or reason for appeal. You can access the records here, and you can find out more about the background here.

Some incomplete sets of records relating to local tribunals are held at local record offices. At ERO we hold the Chelmsford Local Military Tribunal records, because it was largely staffed by Chelmsford Borough Council councillors and was clerked by the clerk to the council. The records are catalogued as D/B 7 M3/2/1; you can find their catalogue entry on Seax here.

Operation War Diary

The National Archives and the Imperial War Museum are running an online project called Operation War Diary. The 1.5 million pages of the unit war diaries kept on the Western Front have been digitised, and TNA and the IWM are asking for volunteers to help reveal the stories contained within them. You can find the Operation War Diary web pages here, and find out more about the project here.

Closer to home…

Chelmsford Civic Society has been awarded a £10,000 Heritage Lottery Fund grant for their project Chelmsford Remembers, which will investigate the impact of the war on our county town.

A new website has recently been launched focusing on men from Southend and district who lost their lives during the war, with details of the names inscribed on memorials, graves, and rolls of honour. You can find the site here: http://www.southend19141918.co.uk/

Havering Museum are asking for Havering residents to contribute memories and photographs of relatives who fought in the war to a memory wall, which will be included in an exhibition launching in August. Find out more here.

You can also keep up with what is going on in Essex on the Last Poppy project blog. Recent posts include:

If you have a resource that would be of use to First World War resources do let us know by writing to hannahjane.salisbury@essex.gov.uk