As the centenary of the founding of the RAF is marked across the country, Archive Assistant Neil Wiffen has been looking at the history of the world’s first air force in Essex.

Orville and Wilbur Wright’s first powered flight of a heavier-than-air-aircraft took place on December 17 1903, just over ten years before the outbreak of the First World War. These first aircraft, despite being primitive, were soon appreciated for their potential to assist with reconnaissance over a battlefield. In Britain the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), to support the army, was established in 1912 while the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was formed in July 1914. With the outbreak of war, the first deployment to support the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in France was of three squadrons with around 60 aircraft.

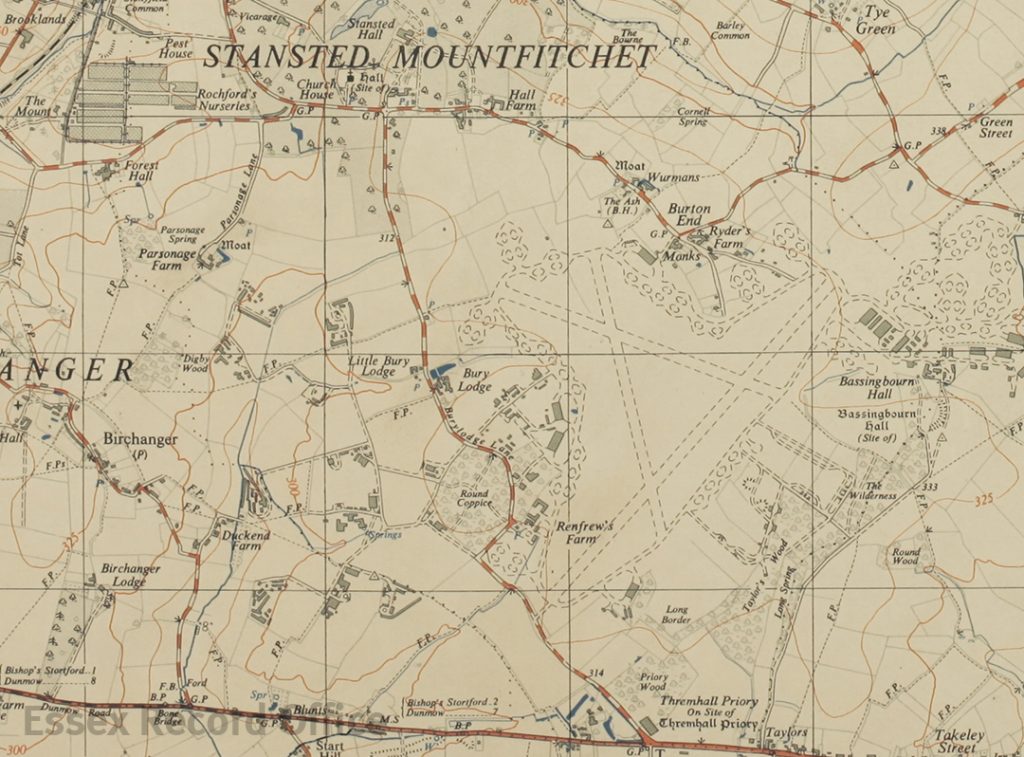

While supporting the BEF was of primary role of the RFC, German air attacks on Britain forced the deployment of Home Defence Squadrons in order to provide some air defence against first Zeppelin and then Gotha bomber raids. The proximity of Essex to London meant that the county was an obvious place in which to base aircraft. The first squadrons were operational by September 1916 with Flights of aircraft being based at Rochford, Stow Maries, Goldhanger, North Weald, Suttons Farm and Hainault Farm.

The Sopwith Camel became one of the most iconic fighter aircraft of the First World War. It was first used on the Western Front, but eventually was used for home defence as well.

Early airfields, or landing grounds, were like early aircraft – basic. Virtually any fairly flat piece of farmland could be utilised to land and fly off aircraft and during the course of the First World War 31 locations in Essex were used with places as far apart as Beaumont near Thorpe-le-Soken, Chingford, Thaxted and Bournes Green, Shoeburyness. The most well-known of these is Stow Maries which still retains many of the buildings that were constructed to support the aircraft and personnel who were based there during the war. (You can read more about Stow Maries here.)

By 1917 official thinking was moving away from having two distinct services to support the army and navy and it was proposed that a single service would make more efficient use of resources. On the 1 April 1918 the RFC and RNAS were combined to form the Royal Air Force, the world’s first independent air force and with over 100,000 personnel and 4,000 aircraft, at the time the world’s largest air force, a far cry from four years earlier.

After the First World War the armed services were cut back, and the RAF did not need so many landing grounds. With so few permanent buildings and infrastructure, the transition back to agriculture came quickly for most sites.

During the 1930s, as Hitler’s Nazi party rose to power and rearmed Germany, the British armed forces expanded again, albeit slowly. The RAF was at the forefront of home defence. Permanent airfields, such as those at Hornchurch, North Weald and Debden were constructed, with well-built brick accommodation for the personnel stationed there as well as large, spacious hangars to help look after the larger and more powerful aircraft that had been developed.

At this point, the aircraft were still mostly biplanes, such as the Hawker Hart and Fury and later the Gloster Gladiator, and were really just modernised versions of the Sopwith Camels of earlier days. These airfields were situated to defend London from German attacks across the North Sea, and they were the most prominent part of RAF Fighter Command’s integrated defensive system, which combined with anti-aircraft guns and barrage balloons, was designed to prevent the German bombers getting though. However, their biplane fighters were starting to look antiquated when compared to the new aircraft being developed by the Luftwaffe.

Gloster Gauntlets belonging to 56 Squadron at North Weald in 1936. The Gauntlet was the last RAF fighter to have an open cockpit, and the penultimate biplane it employed. Image courtesy of North Weald Air Museum.

Fortunately for the RAF, Sidney Cam, of Hawkers, and Reginald Mitchell, of Supermarine, were both engaged in designing the next generation of fighter aircraft, this time monoplanes powered by the Rolls Royce Merlin engine and armed with eight .303 Browning machine guns – double the firepower of the Gladiator. These fighters, the Hurricane and the Spitfire, both flew from Essex airfields during the Battle of Britain (July-October 1940) and were instrumental in defeating the Luftwaffe.

Members of 41 Squadron at RAF Hornchurch during the Second World War (courtesy of Havering Libraries – Local Studies)

It was not only London and other big cities that the Luftwaffe were bombing. This photograph shows bomb damage at Campbell Road in Southend-on-Sea, 4 February 1941. Two men and six women were killed, four men and five women were injured. (D/BC 1/7/7/7)

Once the initial threat was dealt with, the ‘Few’ of the RAF had to be increased to take the fight to the Germans. As part of this expansion new airfields had to be hurriedly built, such as RAF Great Sampford, to take the new squadrons that were being formed and trained. While by the end of the Second World War there were over 20 airfields in Essex, the majority of them new, most had been built for the massive expansion of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF), such as Matching and Boreham.

The majority of the RAF were stationed in the midlands and the north, these being the major concentrations of RAF Bomber Command while Fighter Command fought the Luftwaffe from the east and south of the country, North Weald, and Hornchurch retaining their importance as fighter fields. RAF Bradwell joined them later on in the war, with both night fighters and the RAF’s new Hawker Tempest in the later part of 1944, helping to combat the V1 flying-bomb menace. Things were quieter at North Weald for most of 1945, but excitement returned when Group Captain Douglas Bader, after his release from Colditz Castle in April, was briefly given command of the North Weald Sector. Bader was also chosen to organise a victory flypast on Battle of Britain Day, 15 September, which was made up of some 300 fighters and bombers from both the RAF and USAAF. Bader himself led a Spitfire formation with 11 of his colleagues which took off from North Weald to lead the flypast.

Douglas Bader, centre, led the victory flypast taking off in his own Spitfire from North Weald on 15 September 1945. Image courtesy of North Weald Airfield Museum.

Again, at the end of hostilities the size of the RAF drastically reduced. Most of the wartime-built airfields were quickly disposed of as their Nissen hut accommodation, while suitable for emergency use during the war, were far below the standard of the permanent brick-built barracks constructed in the inter-war years.

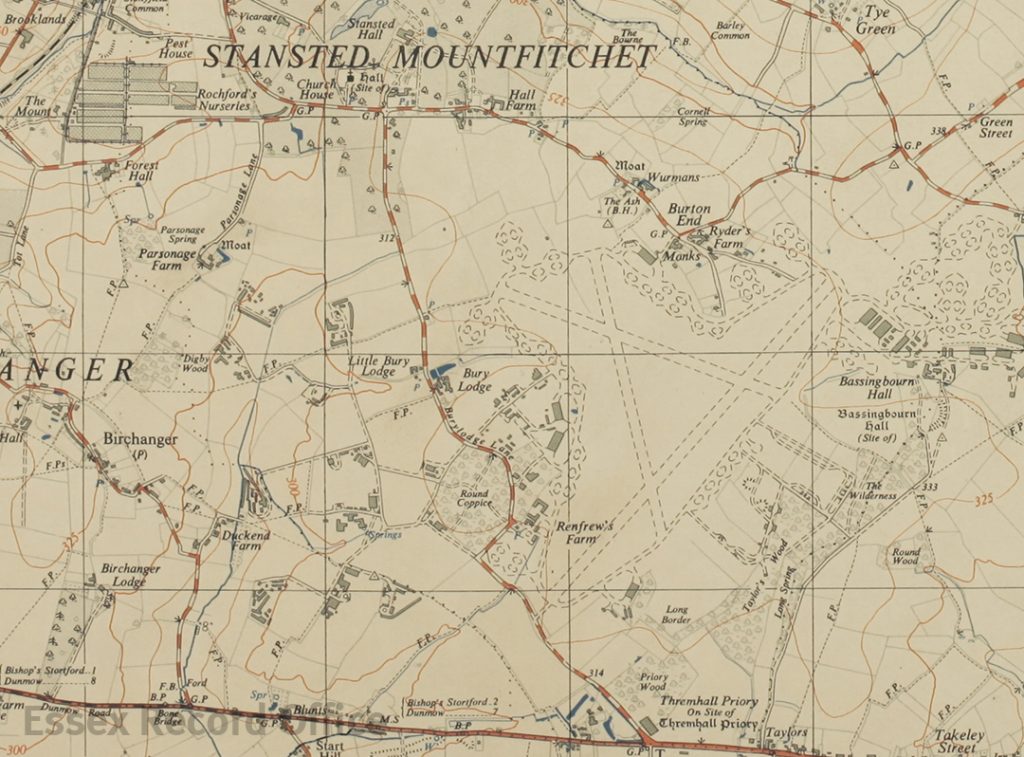

RAF Stansted Mountfitchet, opened in 1943, shown here on a 1956 Ordnance Survey map, was used by the RAF and USAAF during the war as a bomber airfield and major maintenance depot.

However, just as there had been continued improvement of aircraft from biplanes to monoplanes, so now the jet engine aircraft, such as the Gloster Meteor, now took over from the piston-engined Spitfires and Tempests. Along with the new technology so new requirements for servicing and longer runways were required, something which disadvantaged airfields close to London, such as North Weald and Hornchurch. Fast jets and the suburbs did not make for very easy bedfellows. The speeds which could be achieved by new aircraft meant airfields did not have to be so close to London to defend it, and new bases were built nearer to the coasts to intercept Russian bombers over the North Sea.

Most of the RAF bases in Essex closed in 1945 or in the years immediately following the end of the Second World War. RAF Hornchurch remained open until 1962, and RAF North Weald until 1964. RAF Debden is still in the ownership of the military and home to the HQ of the Essex Wing of the RAF Air Cadets and the army’s Carver Barracks. Traces of other former RAF bases have helped to shape our modern landscape; RAF Stansted Mountfitchet became London Stansted Airport, and RAF Southend is now London Southend Airport.

With thanks to Havering Libraries – Local Studies and North Weald Airfield Museum for supplying images for this post.

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.

Can you get to all the benches? Please note the touring bench that was in Raphael Park has now moved to outside the Finchingfield Guildhall. The touring bench in Hadleigh Park will shortly be moving to Weald Country Park.