On this World Day for Audiovisual Heritage, our Sound Archivist Sarah-Joy Maddeaux shares news of a new collection of moving stories that have recently been added to the archive.

What does ‘home’ mean? What does it mean to be ‘British’? What does it mean to be Black in Britain? What can we learn from our elders? And what does all of this have to do with a Caribbean restaurant in Colchester?

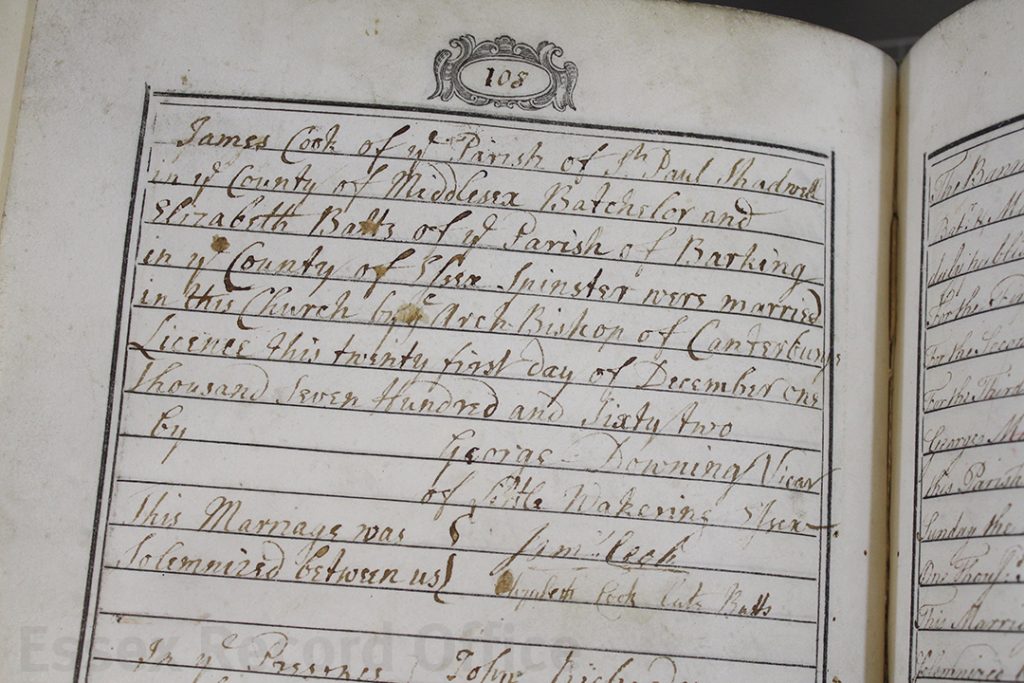

We are delighted to announce that we have received, catalogued, and published the interviews created by Evewright Arts Foundation for their Caribbean Takeaway Takeover exhibition. From 2017 to 2018, artist Everton Wright (EVEWRIGHT), staff, and volunteers of his art foundation recorded oral history interviews with 10 elders who moved to the UK from the Caribbean in the 1940s to 1960s.

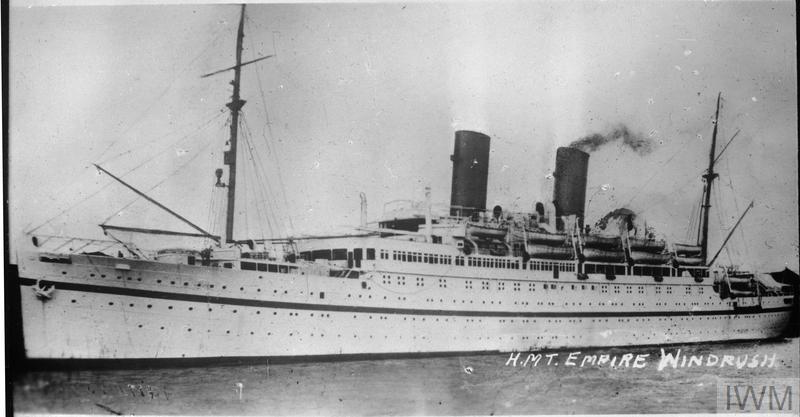

Last summer, on the on the weekend of the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the SS Empire Windrush to Tilbury, Evewright ‘took over’ the S&S Caribbean Café in St Johns Street, Colchester, redecorating the walls and tables with pictures and documents relating to these elders’ lives. Ten-minute segments from their interviews played on a loop in the café, making the exhibition fully immersive. A number of community events encouraged engagement with the exhibition, and thereby with the incredible stories of these elders.

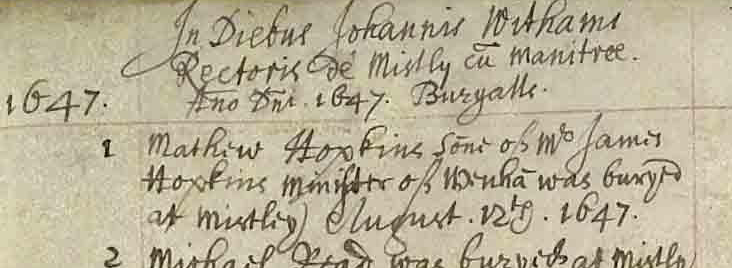

Detail of art installation at S&S Caribbean Café, 2018 (c) Evewright

The elders generously granted us permission to make their interviews freely available through our catalogue. Search for ‘EVEWRIGHT’ on Essex Archives Online, or type ‘SA 69’ in the ‘Document reference’ box to find all ten interviews.

One of the most exciting interviews is that with Alford Gardner. Now aged 92, he is one of the few remaining passengers who travelled on the SS Empire Windrush, the first ship to bring West Indians to settle in post-war Britain. His vivid description of life on board the ship gives an impression of a fun communal experience. His optimism for the future took time to realise, as he faced initial opposition when he tried to settle in Leeds. He was treated very differently in 1948 than when he had previously spent time there as part of the Royal Air Force.

HMS EMPIRE WINDRUSH (FL 9448) Underway Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205120767

Alford Gardner describes the struggle to find accommodation in Leeds in 1948 (SA 69/1/3/1).

As a collection, the interviews reveal a number of similarities in the elders’ experiences, but also some significant differences – factors that determined whether their move was overall a positive step, or a negative one which they came to regret.

As we might expect, many commented on adjusting to cold, wet England, and coming to appreciate the heating that required houses to have chimneys, which in the Caribbean only appeared on factories or bakeries.

Nell Green‘s first impression of the houses in England (SA 69/1/4/1).

Some recalled their first taste of fish and chips – but others were glad that they could access London markets to purchase the tastes of home, such as yams, tanier, dasheen, or plantain.

Carlton Darrell on fish and chips and the weather (SA 69/1/2/1).

In the 1940s to 1960s, British people might have felt like they were being overwhelmed by new arrivals from the Caribbean and other Commonwealth countries, an impression heightened by unfair media portrayals and some politicians stoking fear. However, to the West Indians moving to Britain, black faces were all too scarce. Many interviewees described finding and socialising with other West Indians, particularly in London. Some women became adoptive mothers, inviting young people into their homes and cooking meals for them, helping them adjust to life in this strange, cold country. Was this because it was difficult to make friends with English people? Or was it because we naturally gravitate towards those who share our heritage, with whom we can feel ‘at home’ and recapture something of the country that we left behind?

Carol Sydney‘s social life as a young trainee nurse (SA 69/1/5/1)

Experiences depended, partly, on the financial position and status of the individuals before they moved. Life was easier for those who had money to spend on decent accommodation. Life was also easier if you already had family in England to support you, or if you found a job that you enjoyed and where you were treated with respect. In contrast, it was most difficult for the earliest migrants, the Black people trying to settle in the 1950s amidst Teddy Boy attacks and ‘No cats, no dogs, no Blacks’ signs. It became a little easier for those who arrived in the 1960s and beyond. Many Black people began purchasing their rented homes using a traditional saving scheme called Susu or Pardnor. This enabled them to become landlords to other Black people seeking rooms to rent.

Don Sydney explains the Susu saving scheme that allowed West Indians to support each other in saving up for accommodation and furnishings (SA 69/1/6/1).

Yet, sadly, racist treatment was a shared experience right through the time period covered in the interviews, reported to some extent by each elder.

Carlton Darrell was dismissive of these examples of prejudice against him (SA 69/1/2/1). Is this because he felt it was inevitable, or because he considered himself fortunate compared to others?

Did Britain ever become ‘home’? Yes and no. Some indicated that they still missed their ‘home country’ and wished they could return. Others alluded to a feeling that they were not ‘foreigners’ anymore, but neither were they fully British – even though, coming from Commonwealth countries, they were British subjects before they even set foot on England’s shores.

Carol Sydney reflects on what it means to be ‘British’ (SA 69/1/5/1).

Overall, most of the interviewees were pleased with how their lives had turned out. Does this reflect the type of person they were? That they took the initiative to move to England, the so-called ‘Promised Land’, in search of self-improvement and a better life? Even if they did not believe the ‘streets paved with gold’ promise, many mentioned that Britain did hold a promise of better education, better jobs, and better salaries. Did this proactive attitude make them more resilient, more likely to be happier with what they have accomplished?

Alton Watkins looks back with satisfaction on his life and his accomplishments (SA 69/1/8/1).

They certainly contributed to British society. In their work as nurses, teachers, and midwives, they helped produce the next generation of Britain’s workers. They paid taxes. They contributed to the economy. In retirement, they are volunteering in schools, sports clubs, and libraries.

However, even now, there is more that these elders can contribute. Most of the interviewees acknowledged a persistence of racist attitudes in Britain, some indicating that it is growing worse. Perhaps the interviews, and the exhibition that was held in the summer, will help in the battle to humanise migrants and demonstrate all that they have overcome in their lives.

In this year of the 70th anniversary of the Empire Windrush ship arriving in Tilbury; the 70th anniversary of the foundation of the National Health Service that partly prompted recruitment calls across the Commonwealth; this year of the Windrush scandal, we are grateful to Evewright Arts Foundation for capturing these individual stories that add meaning to national headlines.

And on today, the World Day for Audiovisual Heritage, we are proud to play a part in preserving these ‘Moving Stories’ for the future, and in sharing them with you.

Read more about the Caribbean Takeover Takeaway or find out more about the Evewright Arts Foundation.

All of the interviews can be heard on our SoundCloud channel, or through our online catalogue – search for ‘Evewright’.