Julie Miller, a masters student from University of Essex, has taken up a research placement at the Essex Record Office, conducting an exploration into the story of John Farmer and his adventures, particularly in pre-revolutionary America, and has been jointly funded by the Friends of Historic Essex and University of Essex. Julie will be publishing a series of updates from the 12-week project.

Before looking at the next phase of John Farmer’s life I wanted to look first at the complexities associated with the diaries or journals of people living before the 1750s.

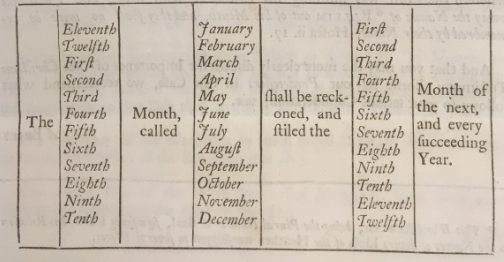

In 1751 England and her empire, including the American colonies, still adhered to the old Julian calendar, which was now eleven days ahead of the Gregorian calendar, introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII and in use in most of Catholic Europe. Years were counted from New Year’s Day being on March 25th, so for example 24th of March was in 1710 and March 25th was in 1711. In addition Quaker’s provided an extra difficulty as they refused to recognise the common names for days of the weeks, or months as they were associated with pagan deities or Roman emperors. So a Quaker would write a date as 1:2mo 1710 which was actually the 1st April 1710 as March was counted as the first month.

In 1751 this all changed when the British government decreed the Gregorian form of calendar was to be adopted and the year would be counted from 1st January 1752. At the 1751 London Meeting for Sufferings the Quakers issued a document advising Friends how to adjust to the new way of counting years but refused to acknowledge the naming of days and months as being based on ‘Popish Superstition’.i

John Farmer’s Journal, stored at the Essex Record Office, is a handwritten account of one man’s travels in the eighteenth century taking the Quaker message to communities in Ireland, Scotland, America and even the Caribbean Islands. Because he was writing in the first quarter of the 18th Century he used old style dating , and the Quaker method for numbering days and months as described above. A first day is a Sunday, a first month is March, so I have calculated all dates into Common Era notation, and dual dated years for dates shown between January and March.

Farmer wrote the journal after he returned in 1714 from his first American journey. He was born in Somerset in 1667, brought up a Baptist, and almost immediately following his Baptism in 1684 he sought fellowship with the Quakers of Stogumber in Somerset and Cullompton in Devon and began work as an itinerant wool comber. He travelled throughout England with his trade before settling in Saffron Walden where he married a fellow Quaker, widow and nurse Mary Fulbigg in 1698 and started family life with his wife, her daughter Mary from her earlier marriage, and they were joined in 1701 by another daughter, Ann. However both John and his wife were also drawn to preaching the Quaker testimony and were prepared to travel many miles in the ministry.

John Farmer quotes numerous biblical tracts within his journal, but one resonates in particular as being his inspiration: “And he said unto ym go ye into all ye world & preach ye gospel to every creature.”ii Gospel of St. Mark, chapter 16, verse 15. And John Farmer certainly travelled far and wide to preach the gospel wherever he could.

The first section of his journal details his intention to have the book published, “for ye good of soules now and in future ages”. The second part details his religious testimony, his early life in Somerset before his conversion to Quakerism, and his struggles with keeping true to his faith. He goes on to describe his travels, alone or occasionally with his wife. He travelled throughout Britain and Ireland holding public meetings to preach his testimony, sometimes with disastrous and occasionally unwittingly humorous results. The third section of the journal is an account of his journey through the eastern states of America, visiting Native American communities and travelling to the islands of the Caribbean, in an extraordinary expedition that lasted nearly 3 years. We will be looking at the various places he visited and the adventures he had in later posts.

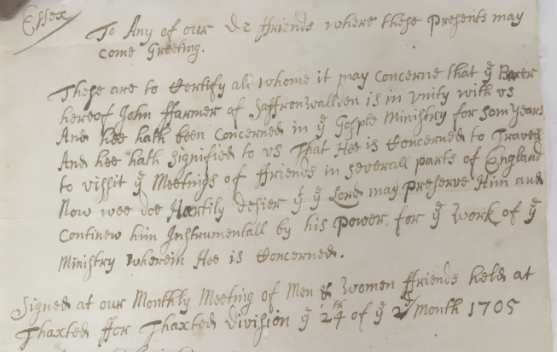

In 1705 Farmer obtained a certificate giving the Thaxted Quaker Monthly Meeting’s blessing on his idea of travelling to ‘severall parts of England.”iii

However when he asked the Saffron Walden Friends to approve his revised plan which was to now include Scotland and Ireland in 1706 he reported there was some opposition to the scheme. A letter in the Essex Record Office archive gives us a clue to the possible attitude of the Thaxted Friends. Written by John Mascall of Finchingfield and dated 25th 2nd month 1707 (25th April 1707) Mascall tells the monthly meeting that “Reciting the case of the Talents Given; to some more, some lesse, which everyone is fitfull to and not go beyond it” he had advised John Farmer to “weight a while… to exercise his talents nearer to home…”iv which must have been very disappointing to a man so desperate to take his testimony out into the world.

This delay led to John Farmer suffering what he saw as God’s chastisement for the delay with a 4-month long bout of piles, an affliction he described as ‘Himrodicall paine’. Clearly this was not a condition beneficial to long expeditions on horseback.

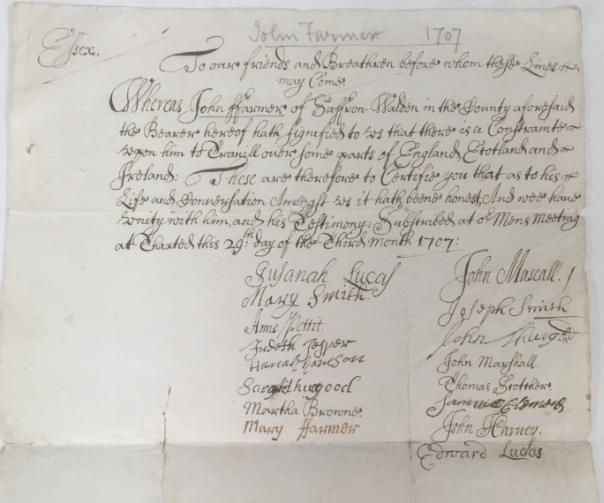

Eventually a certificate was issued by the Thaxted meeting in May 1707 , interestingly signed by both Mary Farmer and the previously doubtful John Mascall, and so John Farmer began his travels in earnest. He and Mary went to Nottingham, and then John went on alone to Scotland.

Whilst in Durham on his way to Scotland John Farmer sent a loving letter to his wife Mary, dated 16th June 1707 where he asks her to send mail care of “Bartie Gibson the Blacksmith of Edinburgh”. He reminds Mary to keep the children reading the bible and “tell ym I would have them remember their creator & love him more than their Idolls”.vi

John made his first visit of six months to Ireland which he briefly covers in saying that he “attended all the meetings there and held several meeting at inns and on the street where people were attentive and civil.” He then headed back to Scotland again where he mentions preaching in Port Patrick, Stranraer, Govern, Ayr, Douglas and elsewhere. He complained some Scottish people were rude and in Penrith, Cumberland (Cumbria) he was assaulted at a Sunday meeting when: “the Divil raged & stired up a man to abuse mee by throwing dirt in my face & striking mee”vii

In Ormskirk John Farmer was imprisoned for a night by the Constable for holding a meeting in the street. From Lancashire where Mary met up again with her husband, the Farmers travelled homeward, stopping in London for the 1708 yearly meeting before going home to Colchester where they had now settled, and where they remained until January 1711 when the urge to travel struck John Farmer yet again.

In the next post we will look at Farmer’s 1711 visit to the West of Ireland, where he was not widely welcomed.

i London Meeting of Sufferings Advice on Regulating Commencement of the Year, 1751, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 52

ii John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p1

iii Thaxted Monthly Meeting Minutes 1705, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 47 Bundle F5

iv Letter from John Mascall 1707, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 47 Bundle F5

v Certificate for John Farmer to travel in the ministry 1705, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 47 Bundle F5

vi Letter from John Farmer to Mary Farmer Durham 1707 Essex Record Office Cat D/NF 3 addl. A13685 Box 51

vii John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p28 [1] John Farmer Journal, Essex Record Office A13685, Box 51, p28