Hannah Salisbury, Engagement and Events Manager

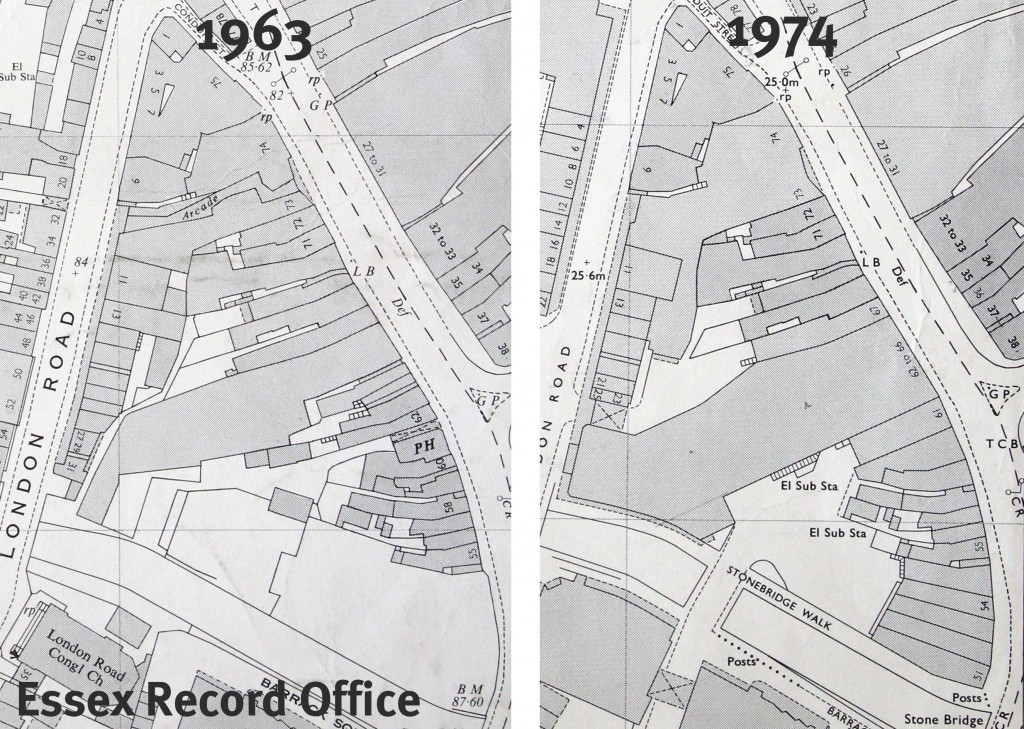

We have two great events coming up in late October looking at the history of Chelmsford. On Wednesday 26 October we have a guided walk of the city centre based on John Walker’s fabulous 1591 map (see below if you have never seen this before), and on Saturday 29 October we are hosting Chelmsford Through Time, a pop-up display of historic maps and photographs, with a talk by Dr James Bettley on the post-war development of Chelmsford. You can find details of both of these on our events webpages.

In preparation for these events we have been sifting through some of the masses of material we have on Chelmsford history, and I thought I would share here five of my favourite Chelmsford items from our collections, that provide fascination snapshots into the past of our county town.

- John Walker’s map, 1591

Any round-up of significant documents of Chelmsford’s history must surely start with John Walker’s spectacular map, dating from 1591 (long-time readers of this blog will most like have come across this in some of our previous posts). It shows the town in exquisite detail, with each building individually drawn with its own doors, windows and chimneys. What’s more, a written survey that goes with the map tells us who was living in each of these properties at the time. It’s a very special window into the past that I never get tired of looking through.

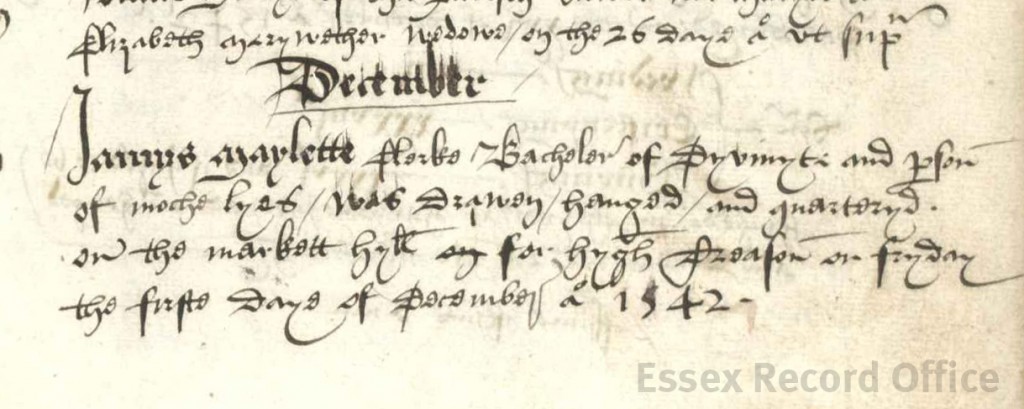

- James Maylett execution

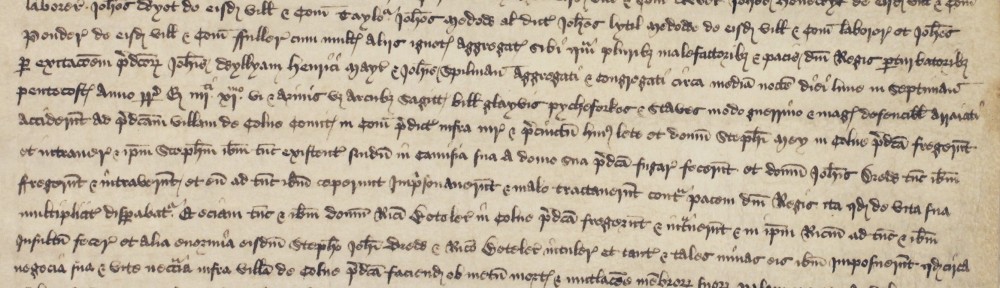

A grimmer choice, but I have always been interested in Tudor history and this snippet from the Chelmsford burial registers serves as a reminder of how brutal life could be. This burial entry dates from December 1542, and reads:

Jamys Maylette clerke Bachelor of Dyvinyti and p[ar]son of moche Lyes was drawen hanged and quarteryd on the market hyll for high treason on fryday the firste daye of December ao 1542.

That is to say, James Mallett, the parson of Great Lees, was hung, drawn and quartered in the market square at Chelmsford for high treason. 1 December that year was a Friday, market day, to ensure maximum witnesses for the gruesome spectacle.

Mallett had been a chaplain to Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII’s first wife whom he divorced in order to marry Anne Boleyn. Mallett had also been rector of Great Leighs for 28 years. His treasonous offence was to comment unfavourably on Henry’s policy of dissolving religious houses. His public execution must surely have been intended as a warning to other clergy not to pass comment on the king’s decisions.

Extract from the Chelmsford parish registers showing the burial of James Mallett, December 1542 (D/P 94/1/4 image 26)

- Spalding photo of High Street, c.1869

This is one of the earliest surviving photographs of Chelmsford High Street, dating to about 1869. It shows a view looking north up the High Street towards Shire Hall. It was taken by Fred Spalding, Chelmsford’s first commercial photographer. Spalding’s son and grandson both became photographers too, and we have about 7,000 of their photographs at the ERO today. This one, like all of Spalding’s early photographs, was taken on a glass plate coated with chemicals; a challenging process to get right, especially in the open air.

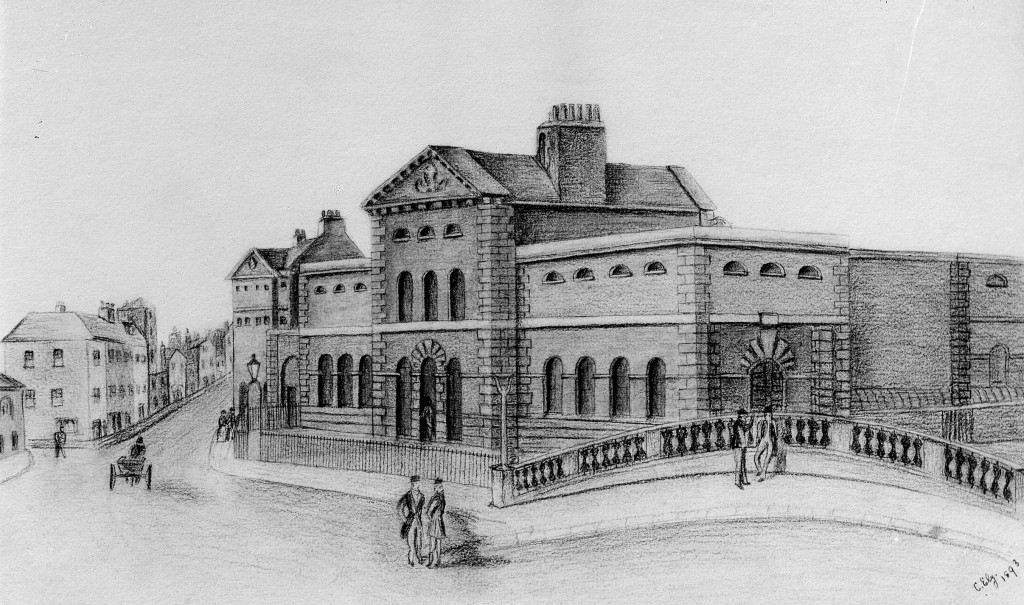

- Photograph of Chelmsford Corn Exchange

If I could wave a magic wand over Chelmsford I would love to be able to bring back the Corn Exchange. This neo-Renaissance building was designed by Fred Chancellor in 1857, and sat on Tindal Square (Shire Hall is just out of frame on the right of this photo). It was demolished, along with the whole of the west side of Tindal Street, to make way for the High Chelmer redevelopment in 1969.

- Women at work in Marconi’s

This photograph is one of a series of images taken of Marconi’s Hall Street works, sometime between 1898 and 1912. At the start of the twentieth century, women were mostly expected to marry, have children, and stay at home. As an archetypal `new’ industry, the wireless industry involved complex assembly operations and `high-tech’ components requiring manual dexterity. The Marconi Hall Street works pioneered the early recruitment of a trained female workforce. Women are so often invisible or difficult to find in historical sources, so to find such striking photographs giving an insight into what their lives were like is always exciting. (You can see some more photos from this set on our Historypin page.)

Join us for Walking with Walker (Wednesday 26 October 2016) or Chelmsford Through Time (Saturday 29 October 2016) to delve deeper into Chelmsford’s history.