In a recent internet deep-dive in search of social media inspiration, we came across a recurring statement declaring Agnes Waterhouse, a local Essex woman, as the first person executed for witchcraft in England in 1566. Marion Gibson, currently a professor at Exeter University, has kindly written this blog post for us, to tell us a little bit more about Agnes and why these claims about her are actually fake news.

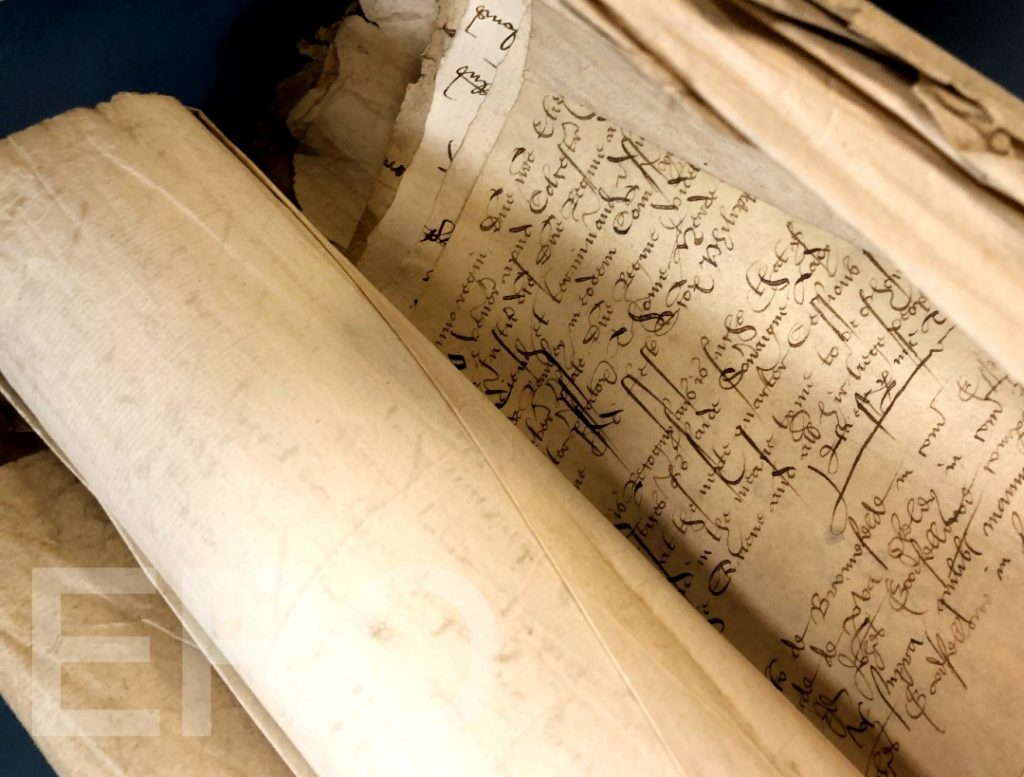

Agnes Waterhouse was a widow from the village of Hatfield Peverel who was tried in Chelmsford for witchcraft in the summer of 1566. It’s as a witchcraft suspect that her name appears on a list of accused felons held by the Essex Record Office, among the Quarter Sessions rolls.

A “felony” was a serious crime, punishable by death, and the group of suspected felons who included Agnes passed through the lower court of Quarter Sessions in 1566 on their way to the higher court of the Assizes. There they would be tried and sentenced.

Agnes was going to the Midsummer Assizes, held in the hot months when England’s top judges got out of London and had time to sit in judgement over suspected provincial criminals. In Chelmsford the Assizes were held in the Market Cross House, which stood just in front of the present-day Shire Hall. The Essex historian Hilda Grieve describes it as:

‘an open-sided building, with eight oak columns supporting upper galleries and a tiled roof. The galleries, which overlooked the open “piazza” below, were lit by three dormer windows in the roof… the magistrates and justices sat in open court, which measured only 26 feet by 24 feet, with the officers of the law, counsel and clerks, plaintiffs and defendants, jurors, sureties, witnesses and prisoners, before and around them, while spectators, hangers-on, and those awaiting their turn, crowded into the galleries above or thronged the street outside.’

The Market Cross House was an unsatisfactory courtroom – packed, noisy and horribly public – but it was Agnes’ destination in summer 1566 after she had been accused as a witch.

Witchcraft was a crime that came to Assize courts regularly, but only after a new Witchcraft Act had been passed by Parliament in 1563. The new Act stated that witches who were convicted of lesser offences – like making farm animals sick – would be punished with one year in prison. Witches who were convicted of killing a person, however, were to be hanged.

Agnes was accused of murder by witchcraft, for which she would be executed if she was found guilty. She was said to have killed her neighbour William Fynee. When questioned, she also admitted harming pigs, cows and geese in her village. Eventually she said she had murdered her own husband in 1557 because they lived “somewhat unquietly” together; it is possible that this confession was drawn out, in part, by some guilt she may have felt over relief at his death and the relative freedom that widowhood granted her.

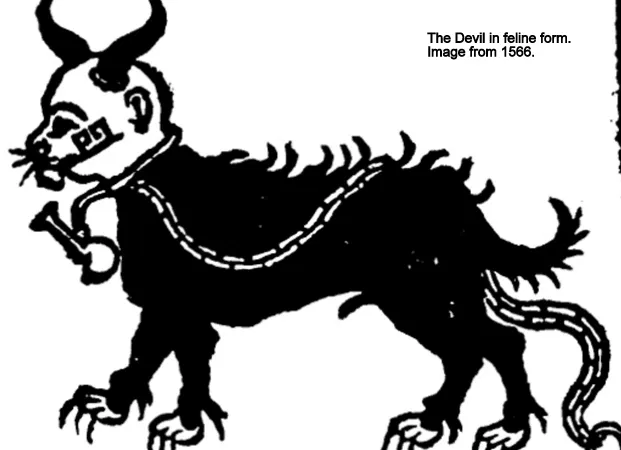

Agnes also confessed to owning a demonic spirit in the form of a pet cat called Sathan, given to her by her sister Elizabeth Fraunces, and this cat had killed her husband and done all the harm of which Agnes stood accused.

Elizabeth Fraunces and also Agnes’ daughter Joan were accused of witchcraft alongside her. Joan was just eighteen years old. She was accused of bewitching another teenager, the Waterhouse’s neighbour Agnes Browne. Joan and her mother, twelve year old Agnes Browne told the court, had sent a black dog to torment her. It brought her the key to the Browne family’s dairy and stole or damaged some of their butter. More seriously, the dog tempted Agnes Browne to suicide by bringing her a knife. He told her this was “his sweet dame’s knife” and when he was asked who this was, Agnes Browne said “he wagged his head to your house, mother Waterhouse”. As well as being a talking dog, this demonic tempter had a monkey’s face and a whistle hung around his neck: a strange beast to see trotting around Hatfield Peverel!

Agnes Waterhouse told Agnes Browne that she was making this story up: “thou liest” she told the girl stoutly. She added that she didn’t even own a dagger. It sounds as though Agnes Waterhouse was in court facing down Agnes Browne – and this account of the trial may be true. But Agnes Waterhouse didn’t need to confront Agnes Browne. She had in fact already pleaded guilty to witchcraft. Most accused felons fought for their lives by pleading “not guilty” but Agnes Waterhouse didn’t. Why did Agnes plead guilty, and why was she still fighting on in the courtroom after she had confessed? The answer is probably Joan. By pleading guilty and then standing beside her daughter to take the blame perhaps Agnes hoped to save Joan from execution.

The case made what we would now think of as “headlines”. Someone gave the statements of the accused witches to a London publisher, who added an eyewitness account of the courtroom scenes, a couple of very bad poems and a description of Agnes’ execution. Yes, that was her fate, and 29th July is the anniversary of her death. Agnes Waterhouse was executed with the other felons convicted at the Assizes, hanged in front of a crowd gathered at the gallows in Chelmsford. The site of her death lies on the road leading towards Writtle.

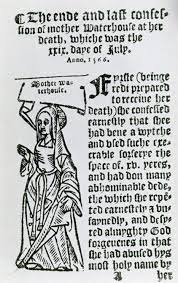

It was a sad end to Agnes’ life, but it was a golden opportunity for journalists. The publisher rushed out a booklet about the case and even added a portrait of Agnes to his story, a woodcut print labelled in blackletter font and showing a woman looking oddly pious, with her hand upraised in blessing. There’s a good reason for this mismatch between story and woodcut.

The picture isn’t actually of Agnes at all. It was just a woodcut from the publisher’s stockroom, with space in the label to insert metal blocks of type. In this way the publisher could give any name to the woman depicted. Witches were usually women, this was a picture of a woman: that would do.

This bit of fake news isn’t the only myth to get stuck to Agnes over the course of the last four hundred and fifty years, however. She’s routinely described as the first witch to be executed for witchcraft in England. In fact, witches had been being executed in England and the wider British Isles for centuries, often because they were judged under laws concerning treason or heresy. Examples include Petronilla de Meath from County Meath, who was executed in 1324 and Margery Jourdemayne from Eye in Suffolk, who was executed in 1441. Both women were burned at the stake. But it is true that Agnes is the first media superstar of the age when witch-hunting got serious in England. She’s a “first witch” because she’s the first witch we know about from a printed news story. In the sixteenth century, that was extraordinary fame.

We should remember Agnes on the anniversary of her execution. She died surrounded by her enemies, likely jeering and jostling for a better view, but she died knowing that her daughter Joan had been acquitted, just as Agnes had hoped.

——————————————————————————————————————–

All the details of the case are taken from the news pamphlet ‘The Examination and Confession of Certaine Wytches at Chensforde in the Countie of Essex (1566)’.

You can read more about Agnes, including the whole text of this pamphlet, in Marion Gibson, ‘Early Modern Witches’ (London: Routledge, 2000)

In the meantime, St Andrews Church in Hatfield Peverel is probably the closest glimpse we can get of the Hatfield Peverel that Agnes knew.

Much of the building dates to the 19th century restoration, but the nave and central tower arch from the original 12th century priory still remain and Agnes would have looked on these features much as we do now, as an enduring memento of history. (Photo by Fred Spalding c.1940)