Neil Wiffen, Public Service Team Manager here at ERO, writes for us about a bombing raid that took off from Essex 70 years ago today…

Seventy years ago the skies above Essex would have been filled daily with the aircraft both of our own Royal Air Force but to a much greater extent by the massed forces of the Eighth and Ninth United States Army Air Forces.

By April 1944 there were eight Bomb Groups of Ninth Air Force Martin B-26 Marauder medium bombers and three groups of Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers in Essex, totalling over 700 aircraft with many thousands of personnel and their supporting units. These aircraft and their crews were tasked with ‘softening up’ the German defences and associated transport infrastructure in Europe in order to facilitate a successful invasion and liberation of occupied territory, something dreamed of, and planned for, since the dark days of June 1940.

Some of these Bomb Groups had been in Essex since the summer of 1943, such as the 387th BG based at Chipping Ongar and the 322nd at Andrew’s Fields (Great Saling). Seven groups were relative newcomers, only arriving ‘in theatre’ in 1944. One of the more recently arrived was the 394th Bomb Group with around 64 B-26s who were based at Boreham, flying their first mission on March 23rd when 36 aircraft set out to bomb a Luftwaffe airfield at Beaumont-le-Roger in France.

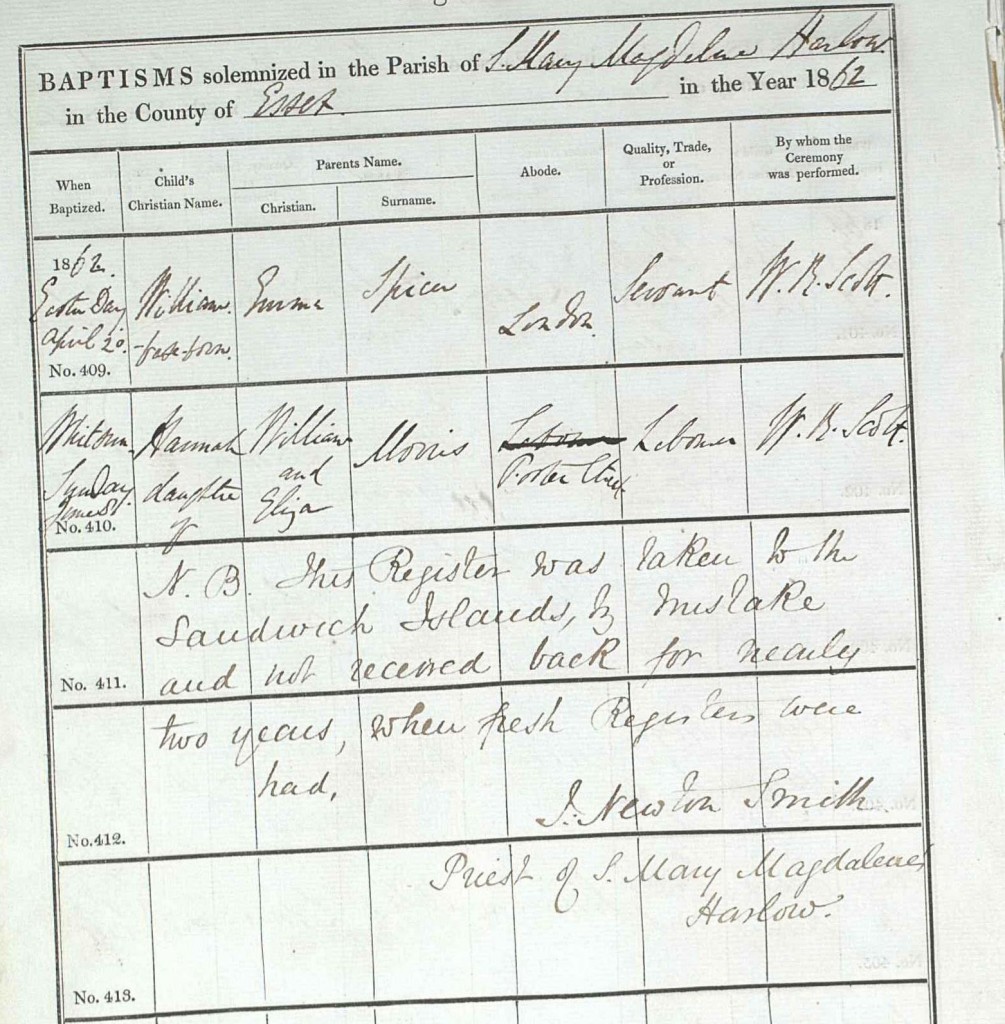

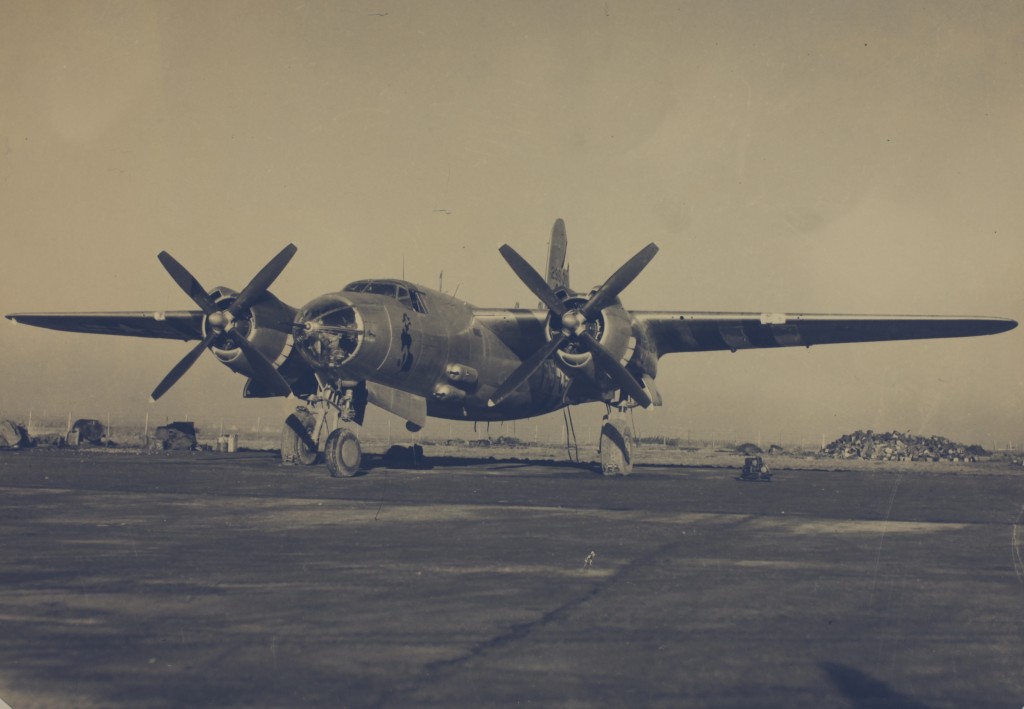

A B-26 Marauder of the 394th Bomb Group (at Boreham?) This was taken sometime after D-Day as evidenced by the worn black and white invasion stripes which can be seen under the wings. Note what appears to be aircraft’s Auxiliary Power Unit under the port wing. This was used to ‘power-up’ the aircraft before main engine ignition. (A10950 Box 1 ‘Book 1’).

Bombing raids were run as regularly as the English weather allowed, with as little let-up as possible, and with sometimes two raids a day. With the date for D-Day set there could be no relaxation for the planners in endeavouring to give the assault troops as much assistance as possible before they hit the beaches. This meant that the Allies’ combined air forces had to keep on pounding away whenever they could.

The 394th was tasked with carrying out one such raid on this day 70 years ago. Their target for what would be their 53rd mission since arriving at Boreham was a bridge in Rouen (J.G Ziegler, Bridge Busters: the story of the 394th Bomb Group (Phoenix, Arizona, 1993), p.38.) This was to be the 10th mission in the last eight days, such was the intensity of the air campaign to date and with only a week to go for the planned launch of D-Day on the 5th June.

One of the 36 Marauders that was designated to fly the mission that morning was being piloted by Lt John Connelly of the 587th Bomb Squadron. Connelly was 11th in line to take off (S.D. Bishop & J.A. Hey, Losses of the US 8th & 9th Air Forces: aircraft and men 1st April – 30th June 1944 (Bury St Edmunds, 2009), p.543). Taking off for a heavily loaded combat aircraft was always a crucial time but especially so for an over loaded twin-engine Marauder. Fat with fuel and armed with two 2,000lb bombs the loss of an engine on take-off could have devastating consequences, and was something which Connelly was about to experience first-hand.

Lt Jack Havener of the 344th over at Stansted later recounted his experience of losing an engine after take-off: ‘We had just taken off…and were about halfway through the first turn to join up…when the right engine started sputtering and losing power. As we frantically clawed the…controls, trying to get some life back into the engine we realised we had a serious problem…By the time I had trimmed for single-engine operation we were still losing altitude, so I gave Sgt Skowski the order to pull the emergency bomb salvo lever…He immediately reached up and pulled the lever and greatly relieved the tension in the cockpit when he yelled out: ‘We got a haystack, Lieutenant!’ Havener and his crew were able to land back to their base – just (R.A. Freeman, B-26 Marauder at War (London, 1978), p.120).

Connelly decided, however, against dumping his bomb load as he decided that opening the bomb-bay doors would cause too much drag and force his Marauder to crash. Trying to regain the runway he was not able to stay aloft and crashed short of it into one of the extensive orchards that once surrounded Boreham airfield. Of the six man crew all survived wounded but Connelly and his co-pilot, Flight Officer Preston Fulgham, received major injuries.

Two views of the Connelly’s Marauder (Serial number 42-96069). How any of the crew survived is unbelievable. Note the bomb lying on the ground. (A10950 Box 1 ‘Book 3’)

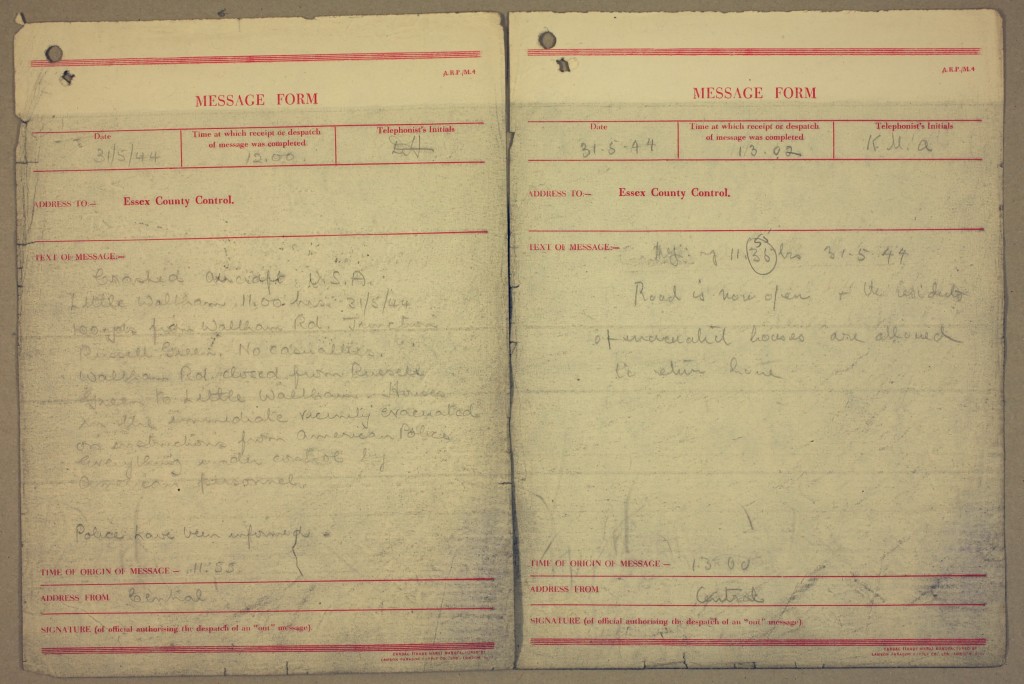

As with all things that fell out of the sky, be they enemy bombs or friendly aircraft, the local authority civil defence system sprang into action. Even though this was an American aircraft and it fell within easy distance of all the US emergency services there were two very large bombs and several hundred gallons of high octane fuel that had been spilled over the Essex countryside. Around mid-day a message was reported to Essex County Control that ‘Waltham Rd. [was] closed from Russell Green to Little Waltham. Houses in the immediate vicinity evacuated on the instruction from American Police’ (ERO, C/W 1/11/3). Shortly after 1pm the road was re-opened and residents allowed back to their properties. While all this was going on the raid that was launched earlier was carried on with – just one more day in a long war.

The Crashed Aircraft Report for 31st May 1944 with the details of the crash from the British viewpoint. (ERO, C/W 1/11/3)

Using the description I wondered if it might be possible to pinpoint the exact location of the crash. The orderly rows of fruit trees show up very well on aerial photos and Looking at am image held at ERO, taken immediately after the end of the war, there does appear to be a scar in the landscape (circled on map), so very close to the runways at Boreham that Connelly nearly made. Seventy years on, I wonder if anyone remembers this event and can confirm the crash site?

Boreham Airfield post war. The runways, taxiways, hardstands and accommodation areas, along with the orchards, are all shown. Circled is the suggested area of the crash. (OS TL71SW, 1:10560)