Ah, the sounds of summer holidays: music blaring through open windows, buzzing bees, the ice cream van, an absence of school bells and cars doing the morning school run… and children playing?

If you believe the common rhetoric, children do not play outside anymore. Children spend all summer indoors glued to electronic screens and no longer have the capacity to invent games, be creative, be free. Is this true? What do Essex soundscapes and personal memories reveal about childhood through the ages?

Sounds of children at play on Dovercourt Beach. Recorded by Stuart Bowditch in 2016 for Essex Sounds.

Childhood memories are a common topic covered in oral history interviews. Interviewers are keen to capture information about the earliest possible period, as the time within ‘living memory’ unceasingly marches forward. We often have the most vivid memories from our childhoods, the time when we are first learning about the world around us. Childhood also tends to be the happiest period, the age we are happiest to talk freely about – or at least the version we are comfortable recalling.

At the Essex Sound and Video Archive, therefore, we have numerous recordings of people talking about their childhoods. For example, this compilation describes the way that people played growing up on Castle Street, Saffron Walden, taken from a selection of interviews recorded for the Castle Street Residents’ Association Oral History Project (Acc. SA496).

Maggie Gyps, Jan Bright, and William Clarke describe playing in and around Castle Street, Saffron Walden in the mid-twentieth century.

The stories are amusing and evoke a golden age when children were free to just have fun. Adults tolerated their exuberance and gave them liberty to range far and wide, making their own games, immersing themselves in nature, packing a jam sandwich and being out all day during summers that were permanently warm and sunny. As the next interviewees remarked, it was a happier time, compared with children today who are mollycoddled, kept on a tight rein due to fears for their safety, and fed on a diet of electronic gadgets to keep them amused – and quiet.

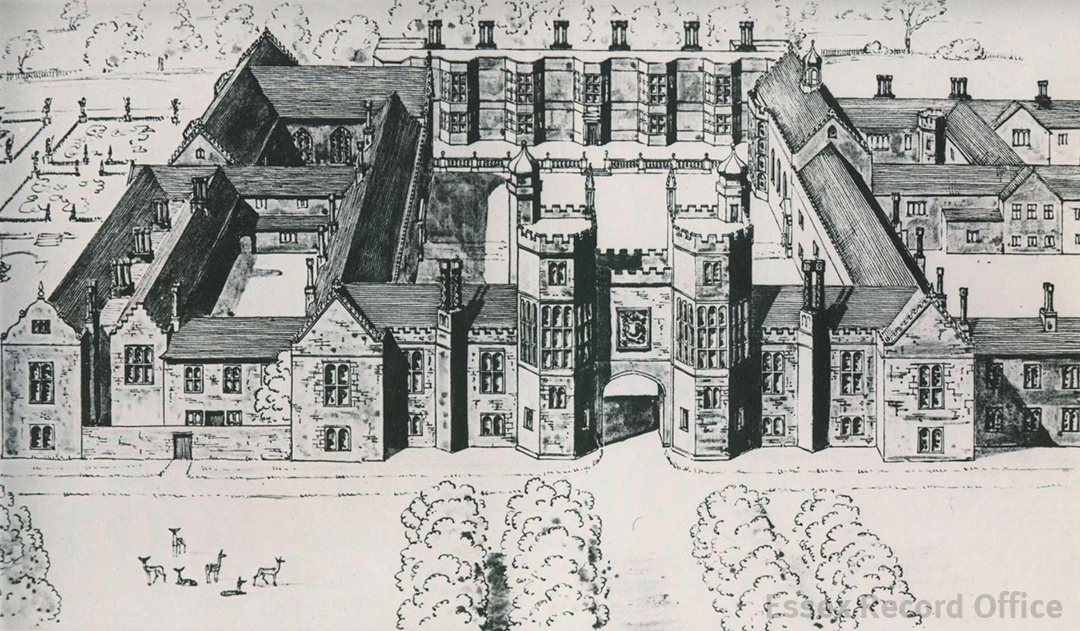

Pearl Scopes and Bill and Daphne Carter ranged free on Marks Hall Estate in the post-war period (SA 51/2/5/1).

Or was it such a golden age? And is it drastically different now?

For our Essex Sounds website, we have two recordings of children at play in north-east Essex: one from 1962, and one made in 2016. Listen to the two and compare: is there a difference in the sounds of play?

Were children better behaved in the past? Many interviewees admit to scrumping, gleaning a bit of fruit from nearby orchards to keep them going on their day-long adventures. We laugh with Bill Carter who ‘borrowed’ his neighbour’s dog to take him rabbiting.

Bill Carter on ‘borrowing’ the neighbour’s dog at Marks Hall Estate (SA 51/2/5/1).

Or Joseph Thomas, who used to sneak into film showings at the Electric Palace in Harwich in the 1920s (SA 49/1/2/15/1).

Joseph Thomas sneaking into the cinema with his friends.

How does this compare with the mischief of those disrespectful youths of today? Will our grandchildren chuckle when they hear stories of what we got up to in our childhood?

Were these children up to no good? Image of Moulsham Street, Chelmsford by Frederick Spalding, 1910 (D/F 269/1/6)

Was childhood really happier in the past? It depends on the individual’s situation, as well as the specific time period. Many oral history interviewees describe working from a young age. Charles Reason, for example, had his first bread round from the age of seven, before he started work full-time after leaving school at 14.

Charles Reason describing his first job delivering bread rolls in Harwich in the 1920s (SA 49/1/2/7/1).

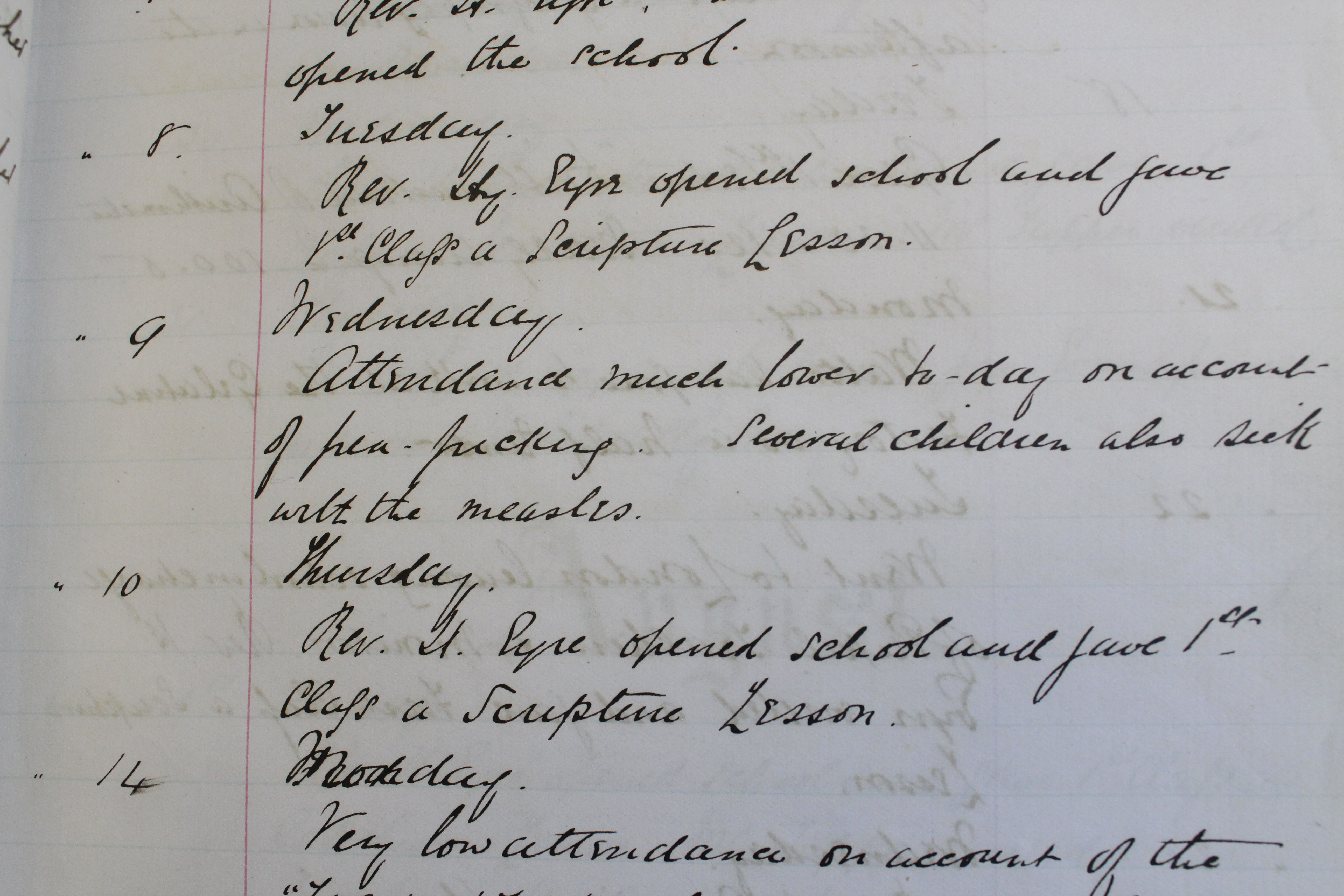

School terms were often set around the harvest seasons, as Gerald Palmer describes, because children stopped attending in order to go pea-picking or fruit-picking anyway (SA 59/1/102/1).

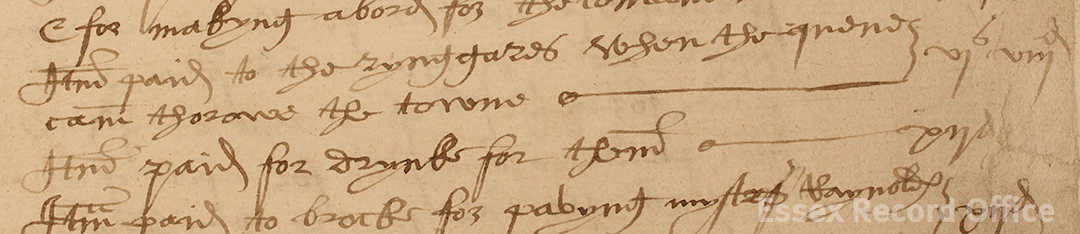

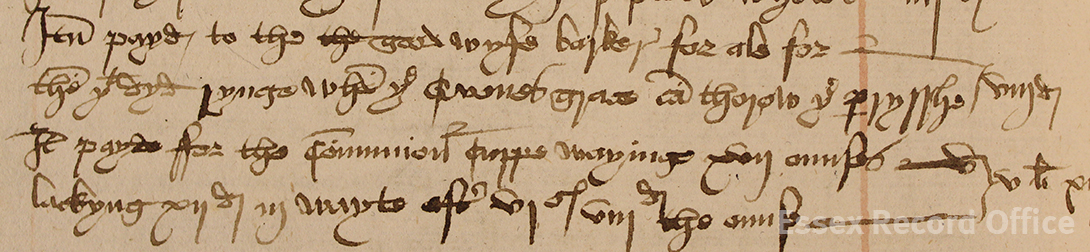

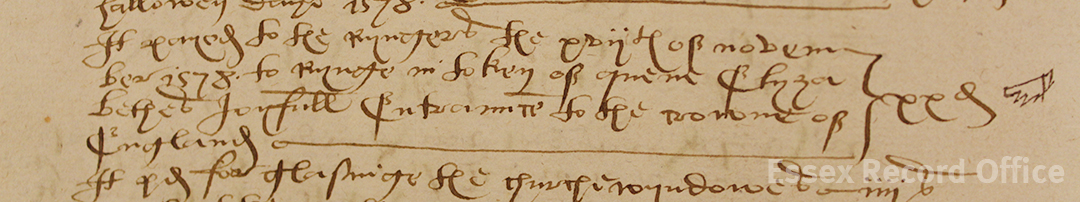

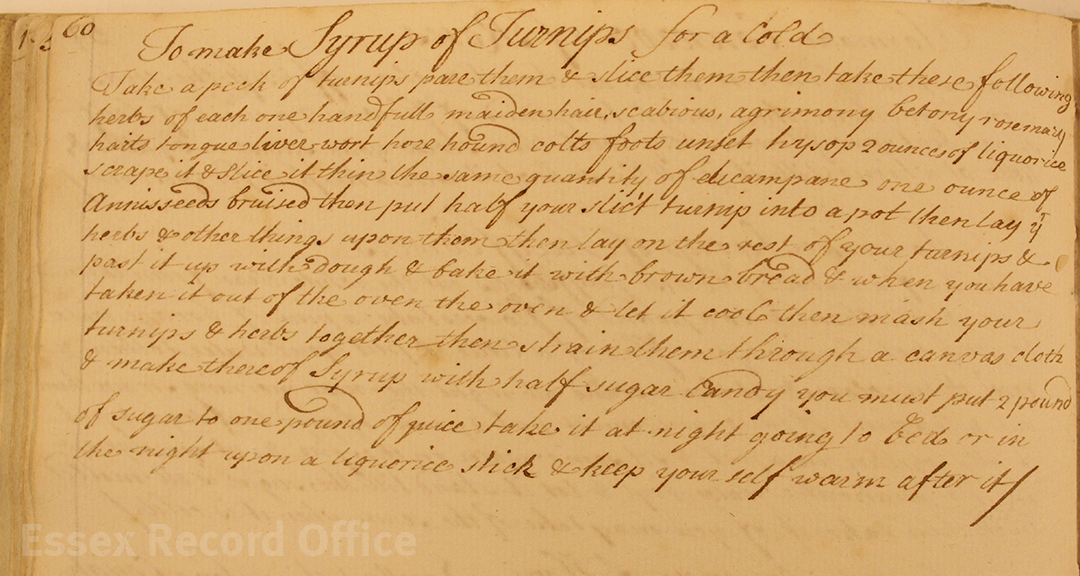

Excerpt from Coggeshall National School log book for 1873 showing low attendance due to pea-picking (E/ML 310/1).

Child labour was vital to the household economy. If children weren’t engaged in paid work, they were often heavily laden with chores around the house, particularly when the mother was absent, as experienced by Rosemary Pitts, whose mother died when she was thirteen years old (SA 55/4/1).

Rosemary Pitts’ memories of childhood in Great Waltham in 1939-1940.

Current scholarship studying Western societies generally traces the start of ‘childhood’ as a distinct phase of life back to the seventeenth century. The nineteenth century saw growing concern about the wellbeing of children, with increasing legislation regulating the employment of young people. In Britain, a series of Education Acts from 1870 onwards gradually made education compulsory and, eventually, free. The 1908 Children’s Act consolidated much previous legislation to protect children from exploitation and abuse (including abuse at the hands of the law). This represents a significant cultural shift: children were seen as vulnerable people to be protected rather than extra hands contributing to the household economy – or enabling cheaper manufacturing. However, many oral history interviews reveal that real change was much slower to take effect. Most people also have at least one memory of a particularly violent punishment suffered by themselves or a peer while at school, in the days of the dreaded cane.

Oral history interviews do tend towards rose-tinted depictions of the past,

particularly childhood memories. However, by comparing many different stories from the same period, we can start to query the common narrative and draw conclusions from specific events rather than vague generalisations. Then we can take a fresh look at children today and reassess if things really have changed that much after all.

The United Nations’ 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child includes the right to play, recognising that it is an essential and characteristic part of childhood. In general, young people in Britain are today free to have fun in their leisure time. It will be interesting to hear how our children recall their formative years if giving oral history interviews later in life. For now, we can use Essex soundscapes to gauge whether or not children still play. What do your ears tell you about childhood in twenty-first-century Essex?

Hugh Cunningham’s book The Invention of Childhood (London: BBC Books, 2006) is an excellent starting place to research the history of childhood in Western societies. For further details of the oral history interviews mentioned above, or other memories of childhood, search Essex Archives Online.