Each year the ERO offers a placement to students on the MA History course at the University of Essex, jointly funded by the university and the Friends of Historic Essex. Last year, we were lucky to be joined by Callum Newton, who catalogued the Essex folk movement oral history project, conducted by Sue Cubbin between 1998 and 2002 (SA 30/7). Over the next three blog posts, Callum delves into the oral histories and chooses some of his personal highlights from the folk collection held in the Essex Sound and Video Archive. In this post, he explains the background to the collection and explores some of the issues discussed in the interviews.

In 1998 Sue Cubbin began an oral history collection that can only be described as a passion project. Inspired by the everyday lives recorded in the Colchester Recalled project (SA 8) she encountered through her work with the Essex Sound Archive, Sue set about conducting interviews with individuals involved in a lifestyle that she herself was deeply enmeshed with: the Essex folk movement.

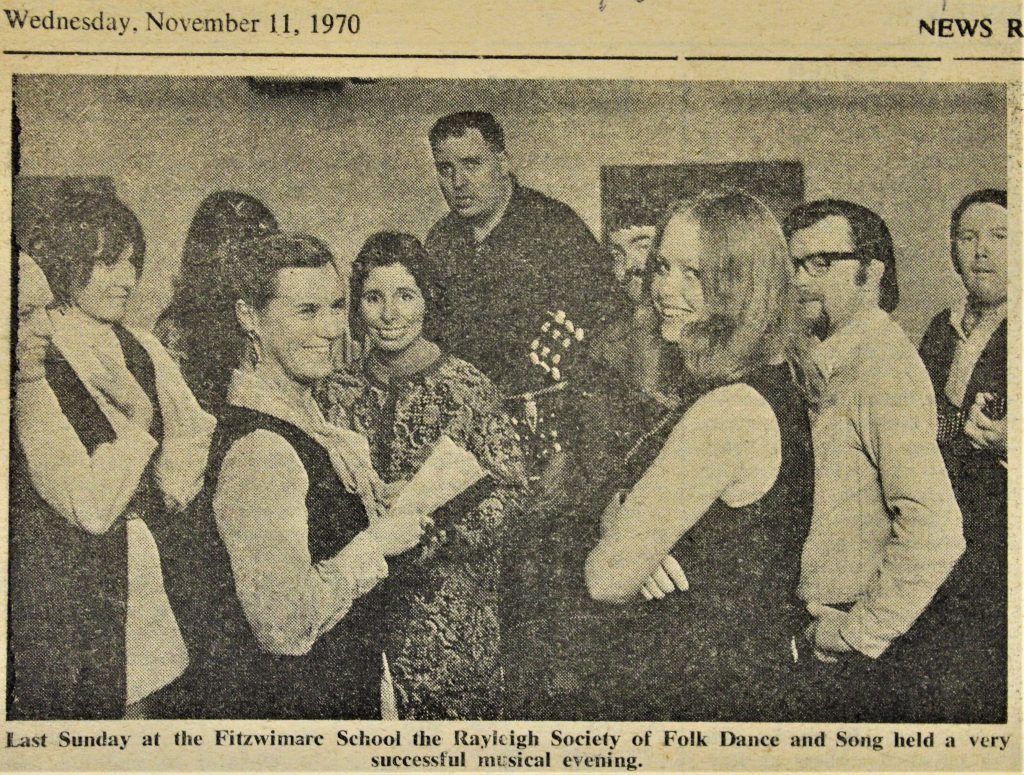

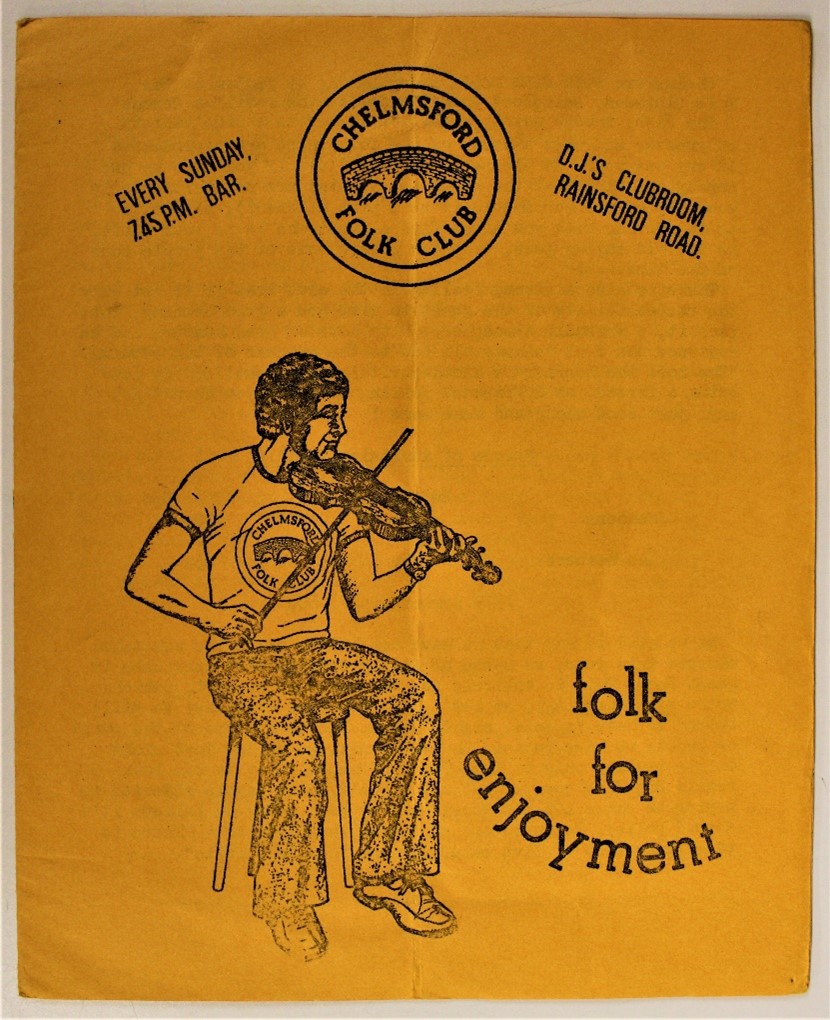

Sue’s belief was that the people involved in preserving the English folk tradition had their lives completely and utterly transformed by their relationship to folk. It was not simply a hobby for those involved; many committed every day of their week to participating in different folk clubs like Blackmore or the Hoy at Anchor. These clubs were home to a dedicated group of singers and musicians, like the Folk Five, Mick and Sarah Graves and the Grand Ceilidh Club. Every year, Essex also became home to folk festivals, most famously at Leigh-on-Sea.

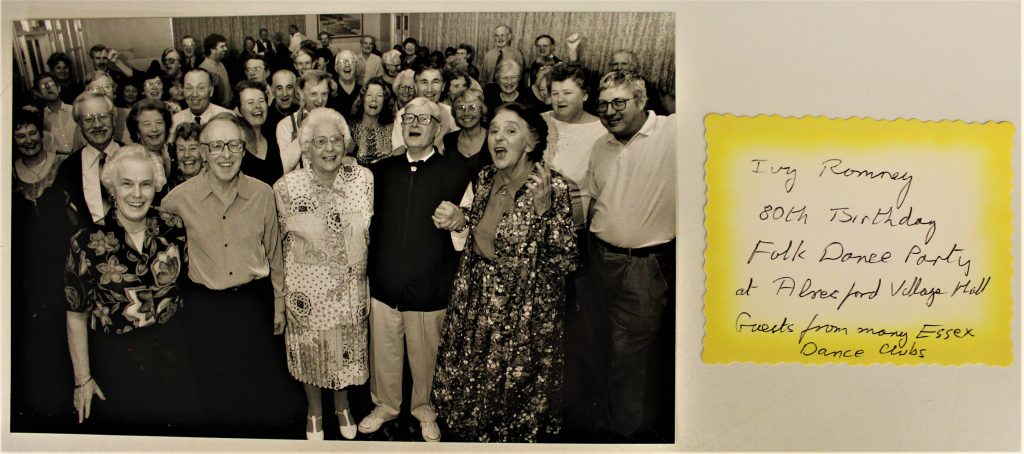

Over the next few years, this archive grew beyond the oral histories to include music recordings, video, photographs, scrap books and all kinds of other assorted materials, all preserved by Sue at the ERO.

From the beginning, Sue saw the project as an opportunity to help protect Essex folk by keeping a record for future generations to be inspired by. This idea is parallel to the oral nature of the folk tradition itself, in which music and dances were inherited generation after generation, by communities for future communities. The nature of this tradition in a modern world, however, was not without question. In a world with commercial records, big-name artists, and large festivals, one might ask what place a folk club might have. As we will see, many interviewees who were patrons of folk clubs asked this same question, suffering a kind of existentialism about the nature of folk and what place their lifestyle and tradition had in a country that often seemed to soundly reject it.

This series of blog posts will explore how the individuals involved interpreted their commitment to the movement, and to the folk revival overall. For the rest of this post, I shall briefly spell out the main themes of the interviews: definitions of folk; the issues posed by commercialisation; and how to keep folk alive. The second and third posts shall explore the story of the folk revival and the nature of the folk movement in Essex.

What is folk?

The definition of folk is not a simple one. To many of us, folk music is often associated with singer-songwriter artists like Bob Dylan or Judy Collins, or perhaps even American country music. Yet many of the interviewees in the collection describe folk as something more: a lifestyle that they commit entirely to, a tradition they have inherited from ‘ordinary people’ of the past. There was not one idea of folk, however. It appears everyone involved had at least their own interpretation of the philosophy.

Some describe it as a continuation of that tradition, a very tangible lineage, rather than something separate or new. But others – like Colin Cater – view this lineage as not necessarily linear.

Others felt strongly that folk was a living tradition, rather than a re-enactment, the ‘folkies’ of Essex often deriding the English Folk Dance and Song Society for aligning with the latter. Folk clubs came under especial scrutiny. Did the music enjoyed locally and communally within these clubs constitute a living tradition? Was having guest performers, on a stage, being watched in silence, contrary to the spirit of a communal folk tradition? Does folk belong to one economic class?

Or, as Paul O’Kelly suggests, is folk for personal enjoyment? Does it need to be communal at all?

Popular folk and commercialisation

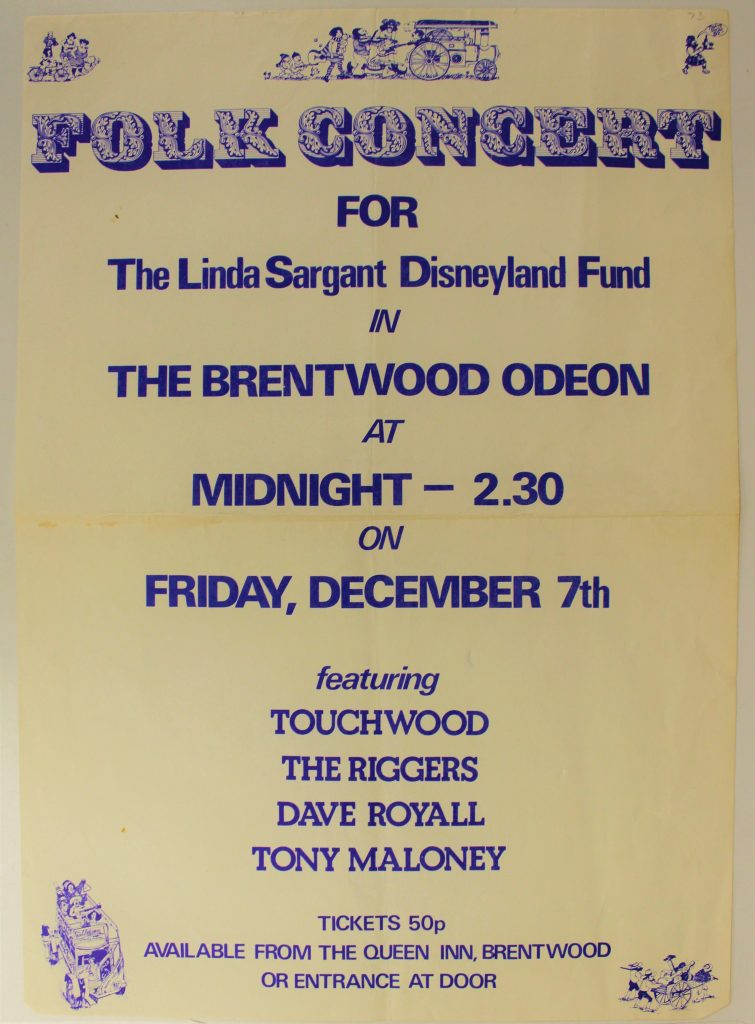

Popular folk music has a fundamental connection to the definition of folk. As the folk revival progressed, many folk practitioners became professional musicians. These artists were writing music, producing records, and gigging under the guise of folk music, very often in folk clubs but certainly within the popular sphere as well. To some of the local folk practitioners, however, this was seen as a degradation of the tradition. Many practitioners thought folk should stay true to its traditional roots, as a communal activity. Putting artists on a stage, separate from its audience, was not considered within their definition of folk, and was even treated as damaging to traditional interpretations of folk music.

This debate also raged within Morris dancing. Those who were lucky enough to be given television appearances were accused of, in the words of Peter Boyce, ‘prostituting’ the tradition, because their costumes were experimental and unique, rather than by the book.

On the other hand, some viewed commercialisation positively. It provided opportunities for those with unique song-writing talent the opportunity to make a living from what they loved and gave folk a platform to present itself positively. Popular folk introduced many of the interviewees to folk clubs in the first place.

Keeping alive and communicating a folk tradition

Unlike the other issues discussed, the interviewees all agreed that more could have been done to keep the folk tradition alive, and that a lack of communication and pride in folk was to blame. Many felt that English people were ashamed of their folk roots, seeing a snobbery or embarrassment that was not present in Irish or Scottish folk traditions. Others tried to encourage the tradition, by writing new dances and songs, as a method of keeping it active and alive, instead of rehashing the older music that some had grown tired of.

Many suggested that young people simply had no interest in folk, with many alternatives for entertainment in a modernising world; none more so than Tony Kendall, who envisioned a revival based in teaching the folk tradition in primary schools across Essex and Britain.

While folk music and dance was certainly still alive when the interviews were recorded, there was an acceptance amongst practitioners that folk was in decline by the 1990s. Some feared this would lead to the folk tradition disappearing altogether, without fast acting documentation.

While the Essex folk tradition does live on, preserved by a dedicated group of practitioners, some twenty years on from when she began, the interviews and the folk song and music collection held at the Essex Record Office acts as an insurance for Essex folk. Forever can the sounds and dances of the movement be experienced and inherited, and the lives attached to the golden age of the folk movement be remembered through their own experiences, in their own words and on their own terms.

Find out more about folk archives preserved at the Essex Record Office in this guide: Sources on Folk Music.