Following on from his first blog post about the Essex folk movement oral history project and his second about the folk revival in England, MA placement student Callum Newton explores what the folk movement looked – and sounded – like in Essex from the 1960s.

Folk clubs

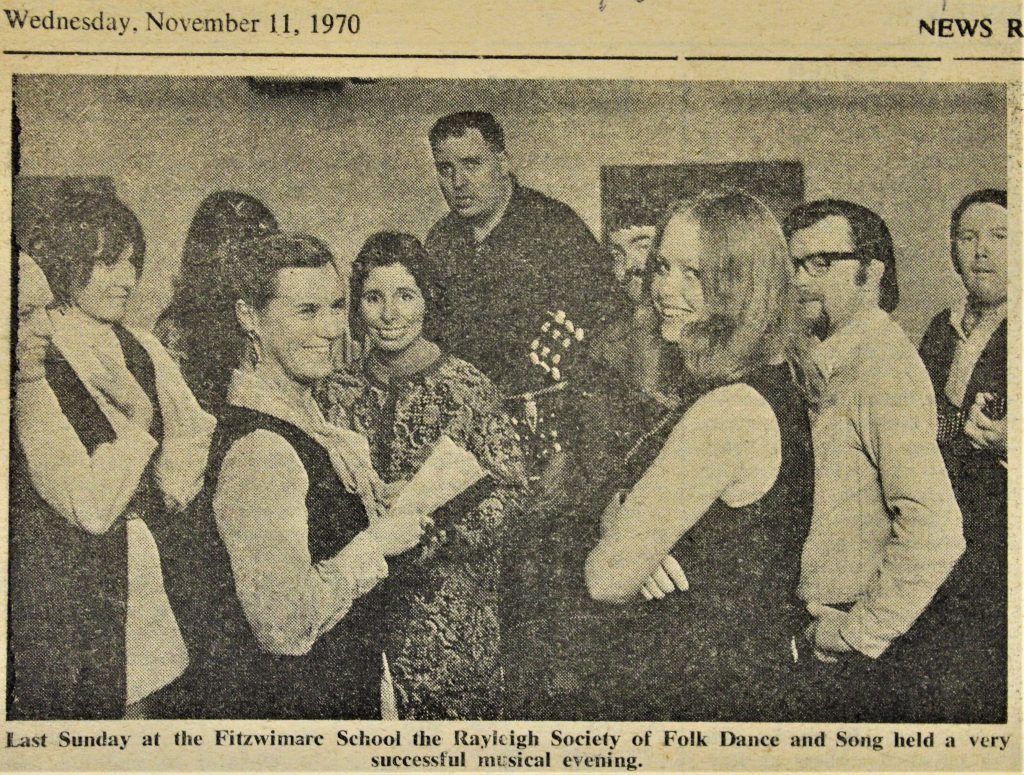

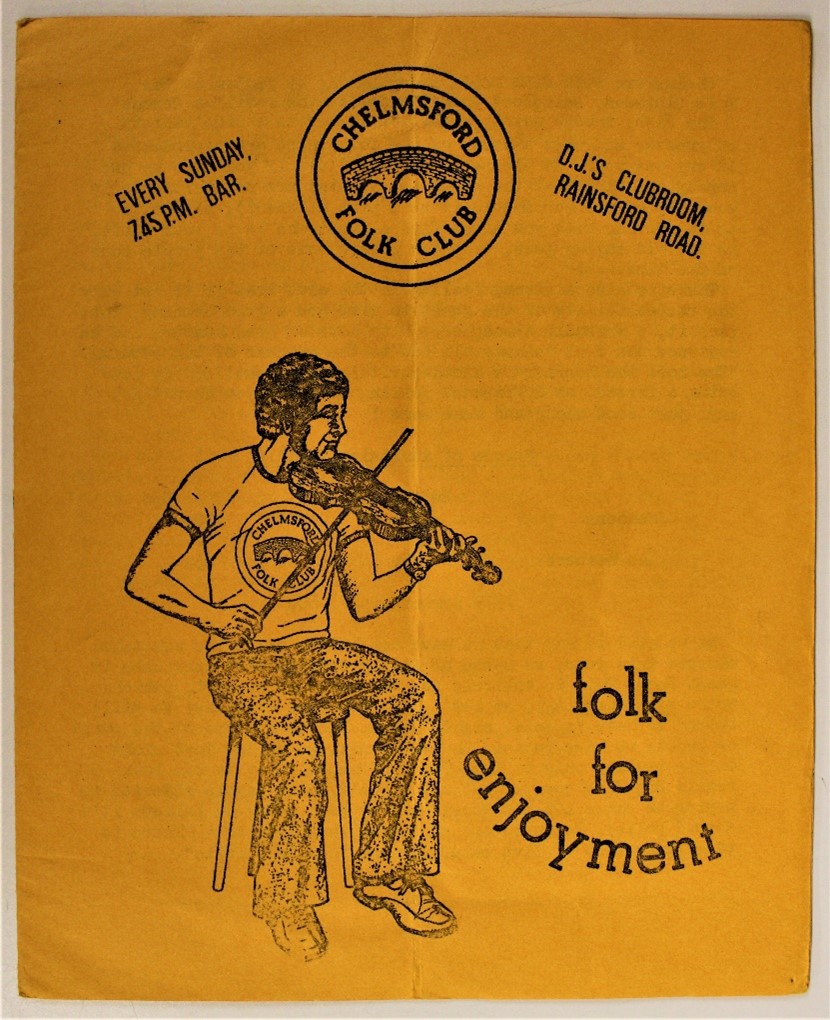

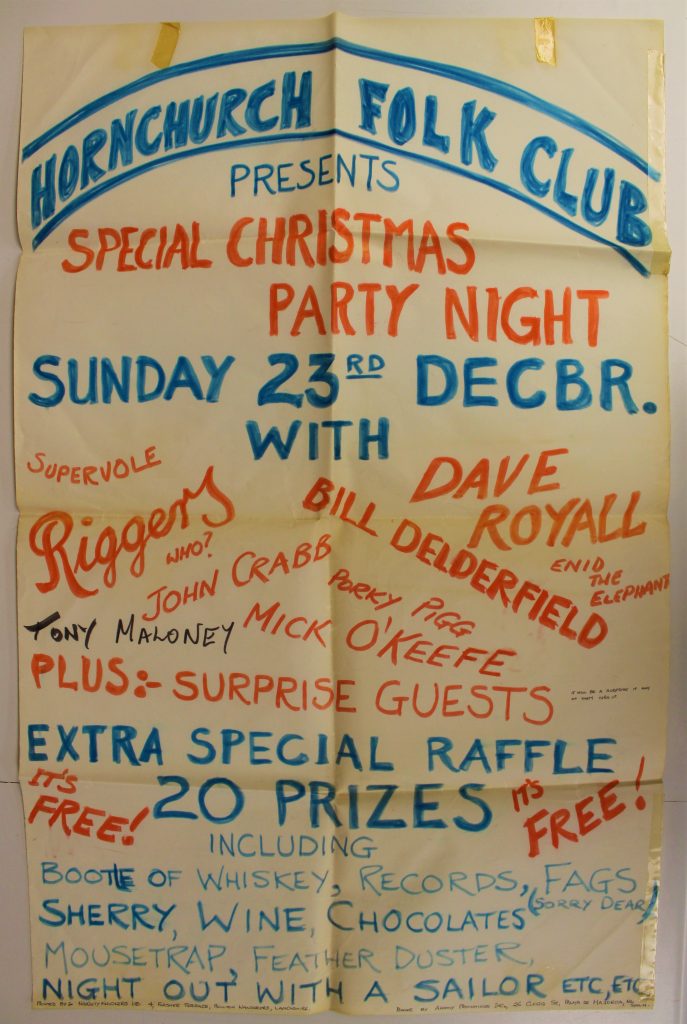

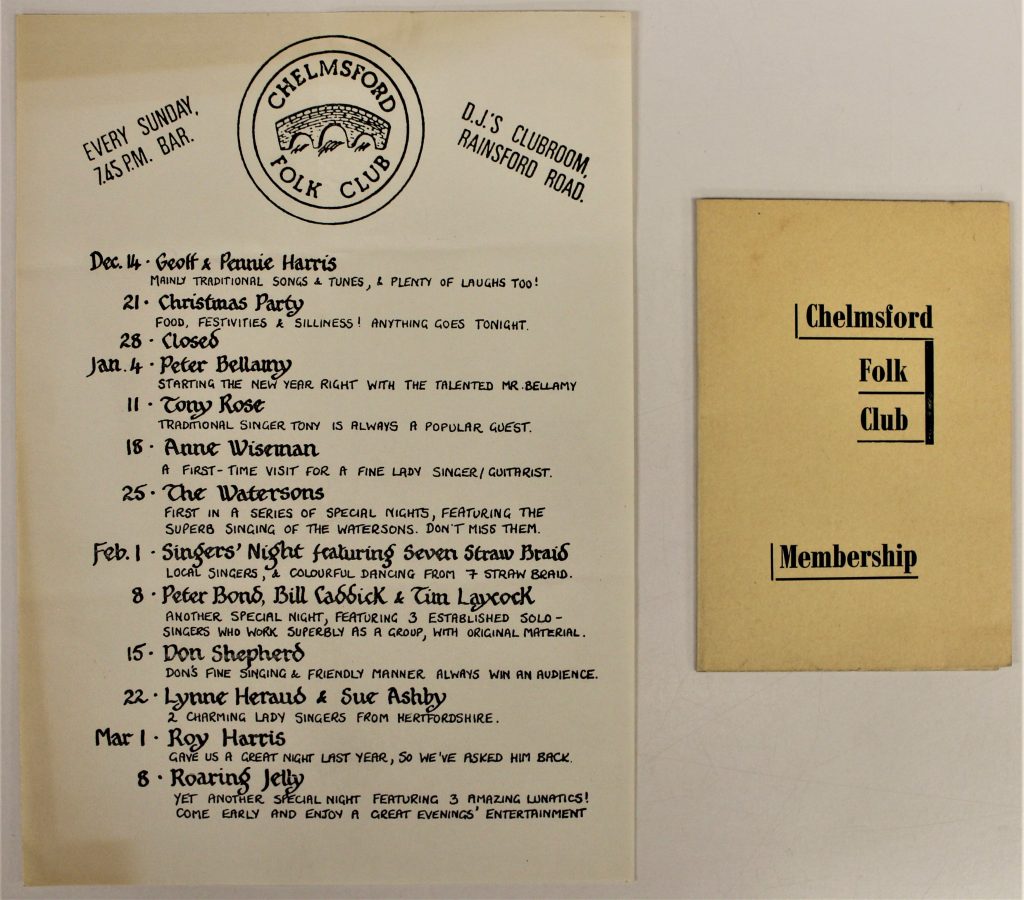

Those interviewed for the Essex folk movement oral history project recall a very active folk club circuit around all areas of Essex, with the more prominent clubs being Blackmore Folk Club, Chelmsford Folk Club, and the Hoy at Anchor in Southend. Blackmore’s influence is felt particularly in the interviews, as Sue Cubbin, the interviewer, and several of the interviewees – including Simon Ritchie, Annie Harding, Jim Garrett and Paul O’Kelly – had performed either within the club or with Blackmore’s associated Morris team. Ritchie, Cubbin and Roger Johnson had also participated in running the club at various stages.

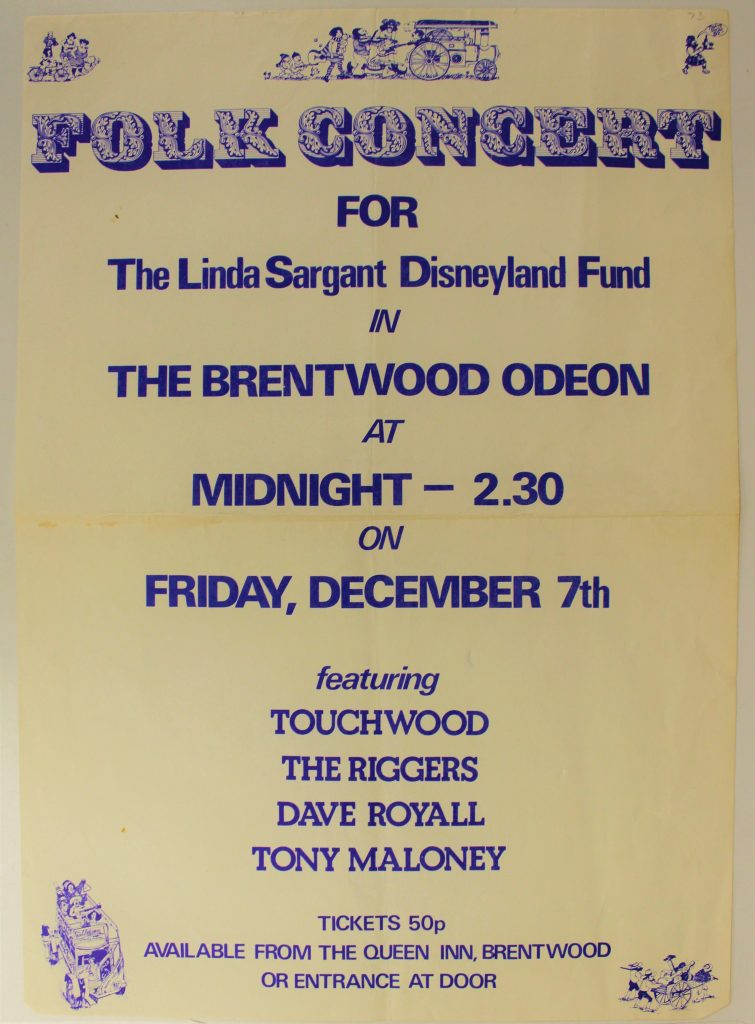

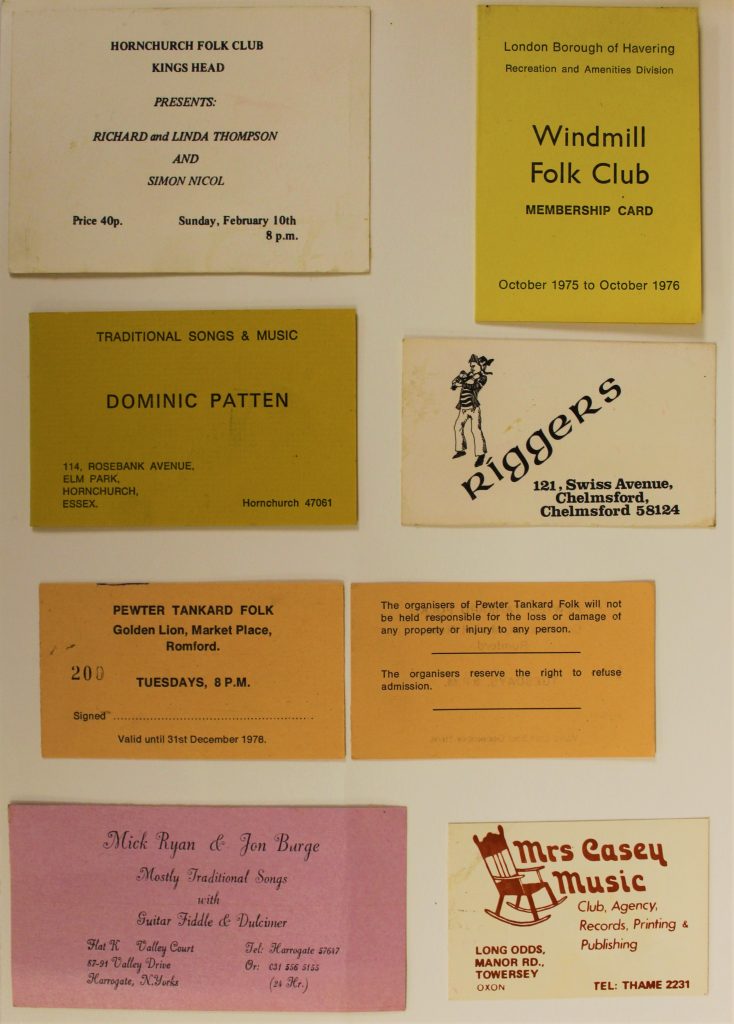

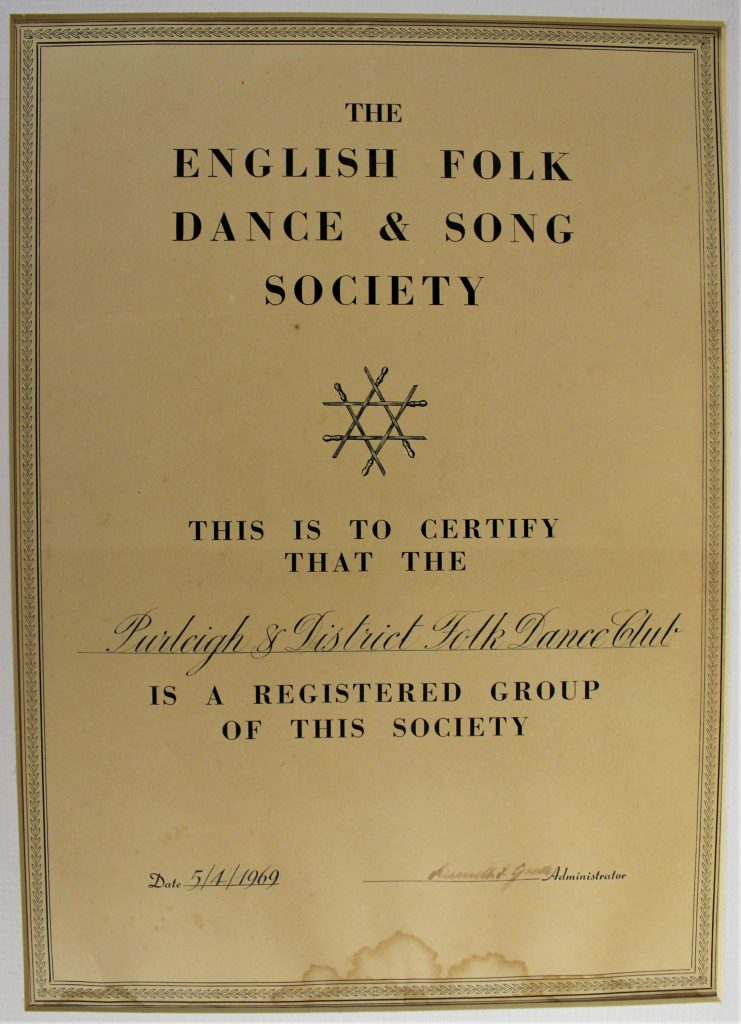

There were dozens of folk clubs across the county, however, from Harwich to Colchester and as far as Brentwood and Havering. Associated with the Essex Folk Association (EFA), or the earlier Essex District Committee of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, all of them were documented in Essex Folk News [LIB/PER 2/22/1-50], so that every club was regularly accessible to anyone involved in the movement.

Essex’s relationship with the larger London folk circuit is also evident due to its geographical relationship. Many practitioners were born in London, discovered folk and later moved to Essex, like Jill-Palmer Swift; or travelled to London specifically for folk, like Dave Vandoorn who ran his first folk club in East Ham in the 1960s despite working in Brentwood.

The close proximity no doubt enabled practitioners to travel between: many already worked in London, like Reg Beecham and Simon Ritchie; or others simply travelled to perform, like Alie Byrne and Jim Garrett. There were considerable differences between the two locations however – while Byrne cites the typically younger audience members in London,Jill Palmer-Swift had always noted the typically wider mix of ethnicities present in London’s folk clubs.

The role of folk clubs was not universal – some existed to have performers, to be watched by those who attended, while others encouraged group singing lead by a particular performer [1].

This was certainly the case, also, in Essex. Paul Kiff describes how the Old Ship in Heybridge acted as a more informal club, entirely focused on singarounds.

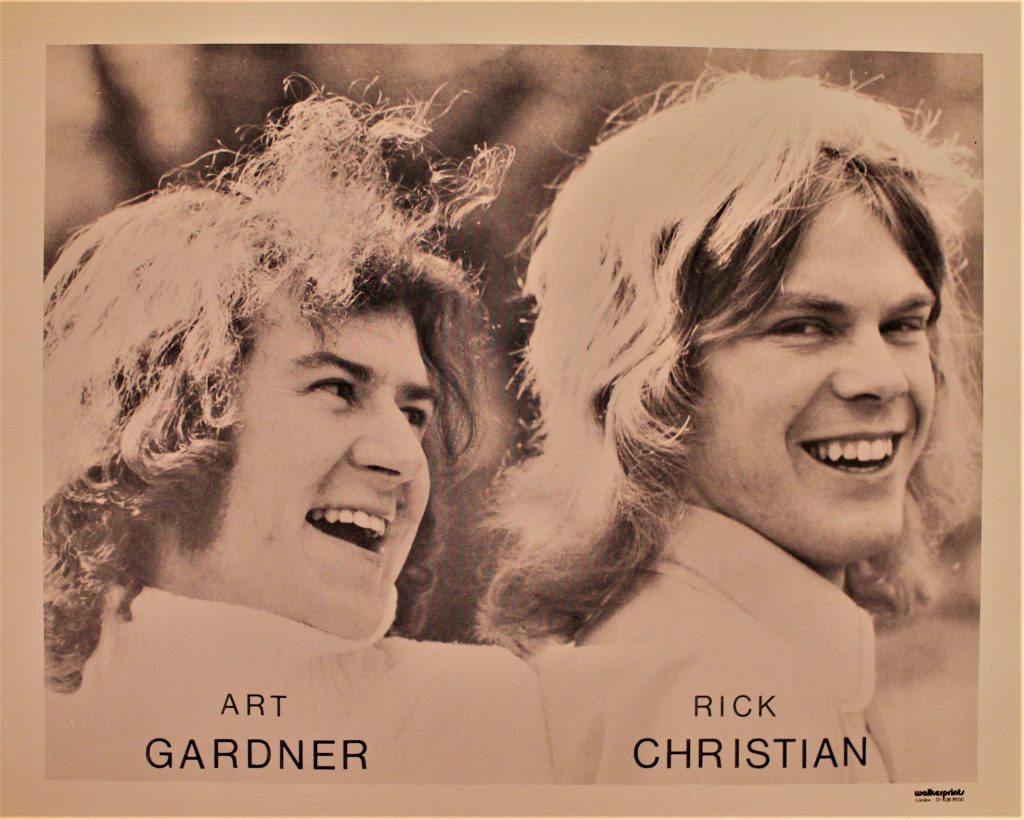

This stands in contrast to a club like Maldon Folk Club, where performers were specifically booked by the host, Rick Christian. It is crucial to consider the individual philosophies of those who ran folk clubs; Christian maintained a professional folk career, and this certainly bled into his organisation of folk festivals, where the performer tends to be the focal point. Paul Kiff, on the other hand, openly rejected festivals and artists as the centre of performance entirely, citing that it was against the tradition, while maintaining a reformist political career within the EFDSS. Ultimately, this is just one of the themes central to finding a definition for the tradition – as in, what is legitimate folk? Sometimes, the vocal, passionate people involved would split bands, or even entire clubs over their position on that question (for more on this topic, see the interviews with Simon Ritchie and Myra and Red Abbott).

Repertoire

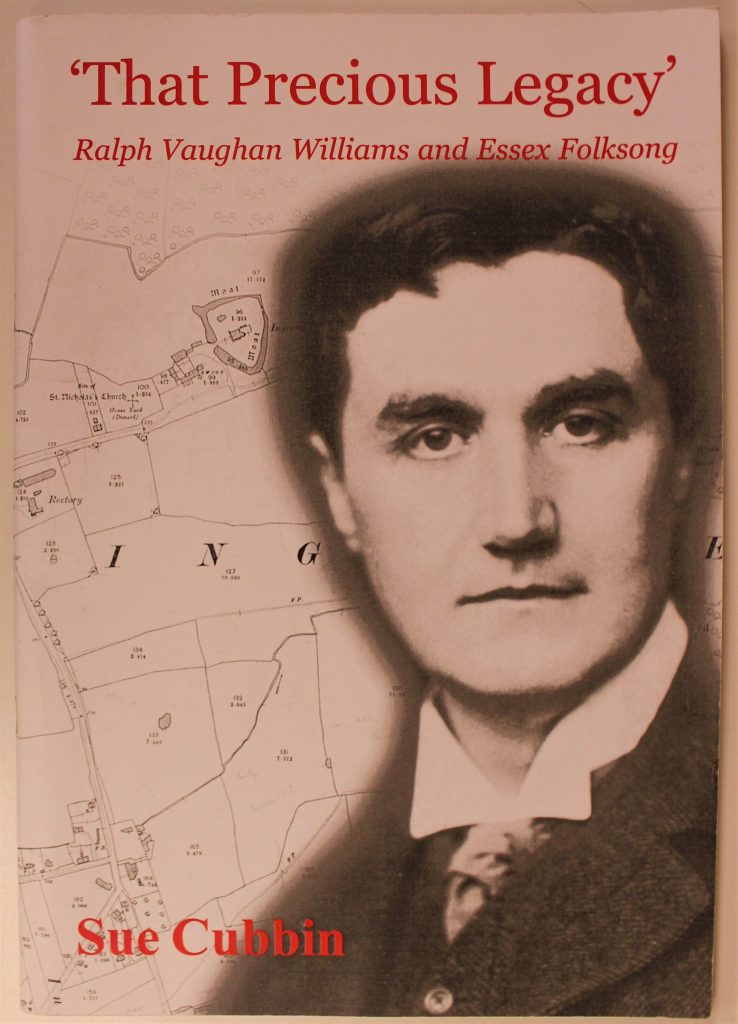

Essex had a very pronounced tradition of its own – largely attributed to the song collections of Vaughan Williams but also from particularly Essex dances like ‘Sally’s Taste’, ‘The Tartar’ and ‘A Trip to Dunmow’ as discovered by John Smith and Jim Youngs (as referenced in interviews with Tony Kendall and Jill Palmer-Swift).

The songs themselves were also a point of contention by some who practiced folk music. Don Budds explained that to his band the Folk Five, folk was an orthodoxy of strictly ‘modal’ style songs like “Maids when You’re Young” or “My Bonny Boy” (see also copy of the Folk Five repertoire, SA 30/1/37/3).

Peter Chopping described folk songs as ‘workers songs; sea-shanties, capstan shanties and halyard shanties’ as well as ‘forebitter’ songs – all some form of worker chant or sea-shanty. Others were less strict; Annie Harding, for example, opted to incorporate jazz and other types of non-folk into her folk act repertoire, alongside traditional songs.

Alie Byrne is indicative of this less orthodox approach as the tradition progressed, as a relative newcomer to the folk scene even at the time of the interview. She suggests that there is a fundamental difference between performing folk and listening to folk, and that while some audiences were strict about ‘purist’ songs “they’ve heard before”, others were more appreciative of less orthodox, more experimental songs. She describes folk as a common ownership of songs, and that there is no one way to perform any song, and that every performer “owns” a song at the moment they are performing it. Byrne’s depiction of folk is a more romantic approach, though certainly this was not always generally accepted. It is certain that there was no universally accepted way to perform folk, even by the people actively performing it, and that the philosophy was actively argued inside and outside of clubs, or between clubs.

The EFDSS and the Essex Folk Association

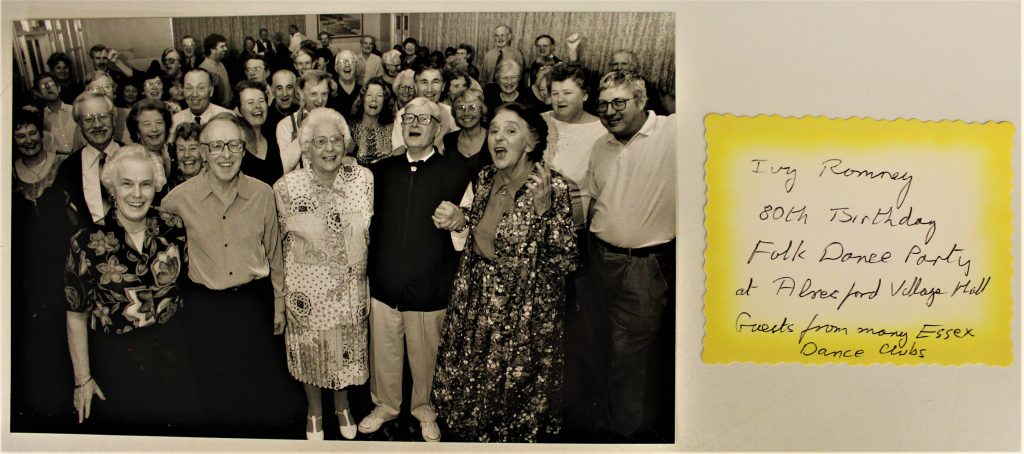

The politics and philosophy of folk was felt quite heavily within Essex, induced by Essex’s relationship with the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), which was seemingly tumultuous at the best of times. In 1995, the Essex Folk Association was founded from the remnants of the Essex District Committee of the EFDSS [EFN Spring 1995, LIB/PER 2/22/23]. Instead of being a regional committee of the EFDSS, the Association instead adopted affiliate status and organised its own affairs. Ivy Romney and Paul Kiff both explore the arguments for this – with Romney claiming that many believed a “non-English” designation would encourage specifically non-English style dancing and music, of which many clubs existed in Essex, such as Scottish country dancing or Irish music, to associate with the Essex movement.

The EFDSS policy, since its founding, of ‘English only’ had prevented some groups, such as Romney’s own Society for International Folk Dancing, from being incorporated properly into the folk scenes despite the universal theme of folk between them. Paul Kiff, additionally, proposed the idea of affiliated clubs within the EFDSS to give each Association its own direction behind some guiding principles, and suggested that some unspecified but consistent names had held back the folk movement within the executive of the EFDSS. This criticism of the EFDSS is explored within the interviews, with some accusing the EFDSS of gatekeeping, and others proposing that dance was always the priority for Cecil Sharp House.

Practically, as a response to the EFDSS monopoly on folk song collecting, the Essex folk movement is of note for its own individual second-revival collectors. Some of those interviewed, like Dennis Rookard and David Occomore, spent countless hours recording in folk clubs.

These collections – alongside those of other collectors, notably John Durrant and Jim Etheridge – are now housed in the Essex Record Office as part of the wider folk music collection, catalogued as SA 30. Additional recordings made by Dennis Rookard are catalogued as SA 19, and David Occomore as SA 21.

Folklore and oral history are inextricably linked because the traditions of folk were themselves an oral tradition. In a modern world, where recording equipment is practically accessible by any person, oral history with a recorder is seemingly the natural successor to this kind of oral tradition [2]. In the spirit of Ewan MacColl’s radio ballads, which combined elements of song and interview into a documentary, folk can and does exist as a wide-ranging, permanent record of the lifestyle people lived [3].

A folk archive then, like the one idealised by Paul Kiff, is fundamentally an extension of the folk movement itself. The collection housed at the Essex Record Office, and the project Sue Cubbin began in 1998, is fundamentally, itself, the folk tradition in the twenty-first century.

Find out more about folk archives preserved at the Essex Record Office in this guide: Sources on Folk Music.

[1] Bean, Singing from the Floor, p.3

[2] Graham Smith, The Making of Oral History, (2008)https://archives.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/articles/oral_history.html [accessed July 2022]

[3] BBC, The Original BBC Radio Ballads, (2006) https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio2/radioballads/original/orig_history.shtml [accessed July 2022]. To find out more about one of the radio ballads produced by Dennis Rookard, Wind Over Tilbury, see one of our previous blog posts.