Archive Assistant Neil Wiffen reflects on the changing pattern of land usage and the historic value of meadows to the Essex landscape.

There is currently much in the media about climate change and environmental degradation. We hear on almost a daily basis about the threat to different ecosystems and landscapes, as well as about worldwide species loss. We in the UK are not immune, and subjects such as the loss of meadows and the threat to bees are now quite common topics of discussion. Recently the BBC reported that, ‘over 97% of wildflower meadows have been lost since the 1930s, that’s a startling 7.5 million acres (3 million hectares). Species-rich grassland now only covers a mere 1% of the UK’s land area’ (http://www.bbc.co.uk/earth/story/20150702-why-meadows-are-worth-saving).

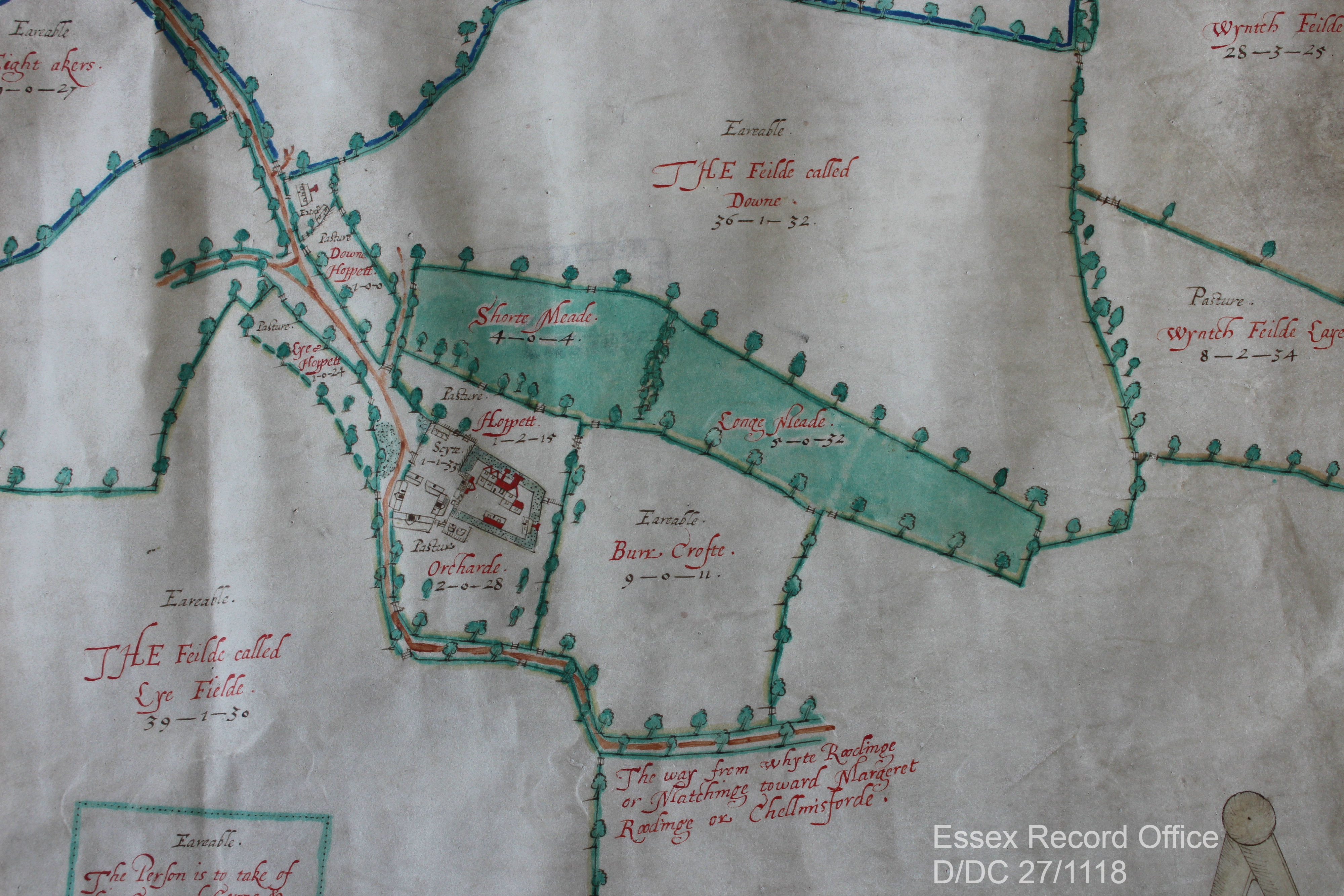

What have bees and meadows got to do with the Essex Record Office (ERO), we hear you ask? Well, working among our wonderful archives we are used to seeing lost landscapes of the past as depicted in maps or described in documents – a land before industrial agriculture and large-scale urbanisation.

One important, almost universal feature of any parish’s landscape would have been that ‘species-rich grassland’ mentioned by the BBC. They were generally described as meadows, which the ERO’s trusty copy of the Oxford English Dictionary (1933) defines as, ‘a piece of land covered with grass that is mown for use as hay. In later use often extended to include any piece of grass land’ (pasture, on the other hand, was used for general grazing of livestock). Look at any tithe, enclosure or estate map and there the meadows will be, often listed and somewhere along the way appraised as well.

— An image of the same location from Google Satellite, 2019.

The importance of meadows to people in the past was immense, particularly before the introduction of fodder crops, such as turnips, through the 17th and 18th centuries. Meadows were mown for hay in summer which was then used to feed overwintering livestock. Therefore the amount of hay harvested determined the number of cattle that could be kept over-winter. So a good hay crop was an essential product of the agricultural year, with the whole community coming together to ensure it was harvested and stored successfully.

The high regard that meadows were held in can be seen by how they were valued. When the Escheator compiled the Inquisition Post Mortem (TNA, C 134/74/19) on the death of Nicholas Dengayne in 1322/3, his manors of Colne Engaine and Prested Hall (Feering) were valued. The 240 acres of arable land in the former was valued at 4 pence per acre, while 140 acres in the latter was 3 pence per acre. By comparison the 6 acres of mowing meadow at Colne Engaine and 5 acres at Prested Hall were all valued at 2 shillings per acre – the equivalent of 24 pence per acre, or six to eight times the value of the arable land.

Quite what types of grasses and flowers these ‘traditional’ meadows were made up of is unknown, but we have to assume in an age before widespread use of agricultural chemicals they were very species rich with lots of insects as well. Not all ‘grassland’ was equal to a well-established meadow. By the 1930s 302,803 acres of ‘permanent grass’ was recorded in Essex (The Land of Britain: the Report of The Land Utilisation Survey of Britain part 82 Essex, copy in ERO Library, Box 95), of which 92,300 was for hay – possibly this was mainly ancient meadows. The remaining 210,503 acres might not have been of the highest quality but rather a result of the agricultural depressions of pre and post First World War. This would have been the case with the 38,977 acres of ‘rough grazing’ – not all grassland was equal!

Now, we are beginning to appreciate our meadows once more and recognise their value as habitats to vital wildlife. While there has been a great loss of meadows, more are being planted, for example by conservation charity Plantlife. Perhaps our maps and documents will guide where new meadows could be sown?

What can you find out about your local landscape history? Check our introduction to the main sources for starting a place history, then come and explore what we have in our Searchroom.