Katharine Schofield and Hannah Salisbury

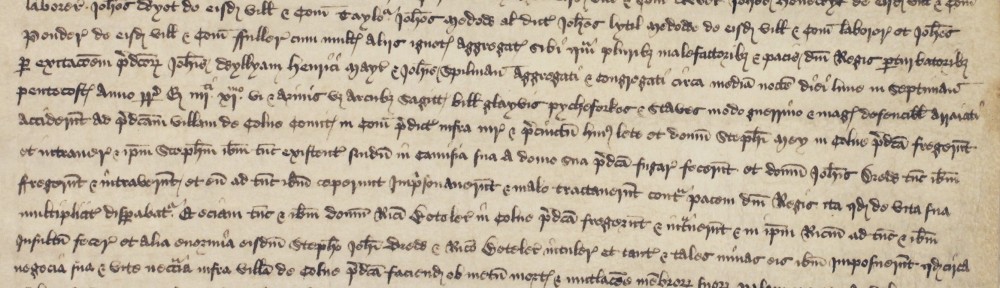

This year, for the first time, we are running a workshop on our Quarter Sessions records. These records provide fascinating glimpses into hundreds of years of the past, and we are fortunate in Essex that our Quarter Sessions records are among the earliest and most complete in the country, dating back to 1555. So much of human life is to be found within these rolls and bundles of documents, and they can provide much of great value for social historians and potentially for genealogists.

Quarter Sessions records come in all shapes and sizes

Later records were bound in volumes rather than stitched into rolls

The roots of the Quarter Sessions can be traced to 1361 when the office of justice of the peace was created to maintain local law and order. By the end of the 14th century they had started to meet quarterly to dispense justice, and these meetings became known as the Quarter Sessions. In addition to their legal duties, the justices soon began to acquire responsibility for other aspects of local life, becoming a centre of local government, until the establishment of the County Council in 1889.

The records created by the Quarter Sessions encompass a huge range of topics, from the licensing of alehouses and printing presses, the maintenance of roads and bridges, the planning of railways and canals, to the prosecution of crime and the running of gaols and houses of correction. (We have mentioned before the Quarter Sessions records which record all public officers.)

Delving in to these records, you might come across the likes of Henry Adcock (alias Cole) of Birdbrook, who was indicted in 1584 for keeping ‘a common house of tipling’, and for allowing Robert Brown, William Butcher, Henry Hempsted and others ‘of evil conversation and idle life’ to play unlawful games, namely ‘cards, tables and quoits’ (Q/SR 90/43). Alehouse keepers were required to take out a bond (called a recognizance) to guarantee good behaviour in their alehouse. To operate without a licence, or break the terms of the licence, left you open to prosecution.

Likewise, the Quarter Sessions tried to keep order amongst food dealers, such as badgers, laders, kidders, carriers of corn, fish, butter or cheese, and cattle drovers. Badgers, kidders and laders were dealers in food which was purchased in one place and carried for sale to another. Like alehouse keepers, these people were required to have licences from the Quarter Sessions, and could be prosecuted if they did not. At the Epiphany 1686 Sessions John Chalke of Leaden Roding and John Green of Moulsham, were indicted ‘both for Common badgers’ (Q/SR 449/46).

Part of the intention was to prevent food dealers from ‘engrossing’ (buying standing crops), ‘forestalling’ (buying goods on the way to market) or ‘regrating’ (buying at market for resale). The Sessions Rolls include many prosecutions for these crimes. The presentments made by the jury for the Hinckford Hundred at the Michaelmas 1588 Sessions included Richard Walford of Castle Hedingham who ‘doe forestall and buy hogges and sell the bacon at an excessive pryce contrary to the lawe’ (Q/SR 106/33).

On a journey into these records you might also find traces of those who were registered to vote or obliged to pay certain taxes. Under the Game Duty Act, from 1784 ‘every person qualified in respect of property to kill game’ had to register their name and abode (Q/RTg 1-4). Likewise, from 1795 persons using hairpowder were obliged to take out an annual certificate with a stamp duty of 1 guinea (Q/RTp 1-3).

Register of those who were licensed to use hair powder in the 1790s

To discover more of these stories for yourself and find out how you could use these records in your own research, come along to Discover: Quarter Sessions Records on Wednesday 11 May, 2.00pm-4.00pm. Tickets are £10 and places are limited, so please book in advance on 033301 32500.

![The deeds are not dated but this one must date from before the second half of 1140, before Geoffrey was made Earl of Essex, as he is named only as G de Mand[eville]. In this deed de Mandeville grants the land of Alan de Scheperitha to Eustace and Humphrey de Barentun. (D/DBa T2/1)](https://i0.wp.com/www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/D-DBa-T2-1-1080-watermarked.jpg?resize=584%2C390&ssl=1)

![In this second deed Geoffrey he is described as Gaufr[ido] Comes Essexe (Geoffrey, Earl of Essex). In this document he confirms a grant of lands in Hatfield [Broad Oak] and Writtle to Humphrey de Barentun. (D/Dba T2/3)](https://i0.wp.com/www.essexrecordofficeblog.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/D-DBa-T2-3-1080-watermarked.jpg?resize=584%2C332&ssl=1)