In this guest blog post, Prof. L.R. Poos shares a preview of the research he will be sharing with us at Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July (more information here). Prof. Poos is an expert in late-medieval and early-modern English social and legal history, and is Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

In this guest blog post, Prof. L.R. Poos shares a preview of the research he will be sharing with us at Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial records on Saturday 12 July (more information here). Prof. Poos is an expert in late-medieval and early-modern English social and legal history, and is Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.

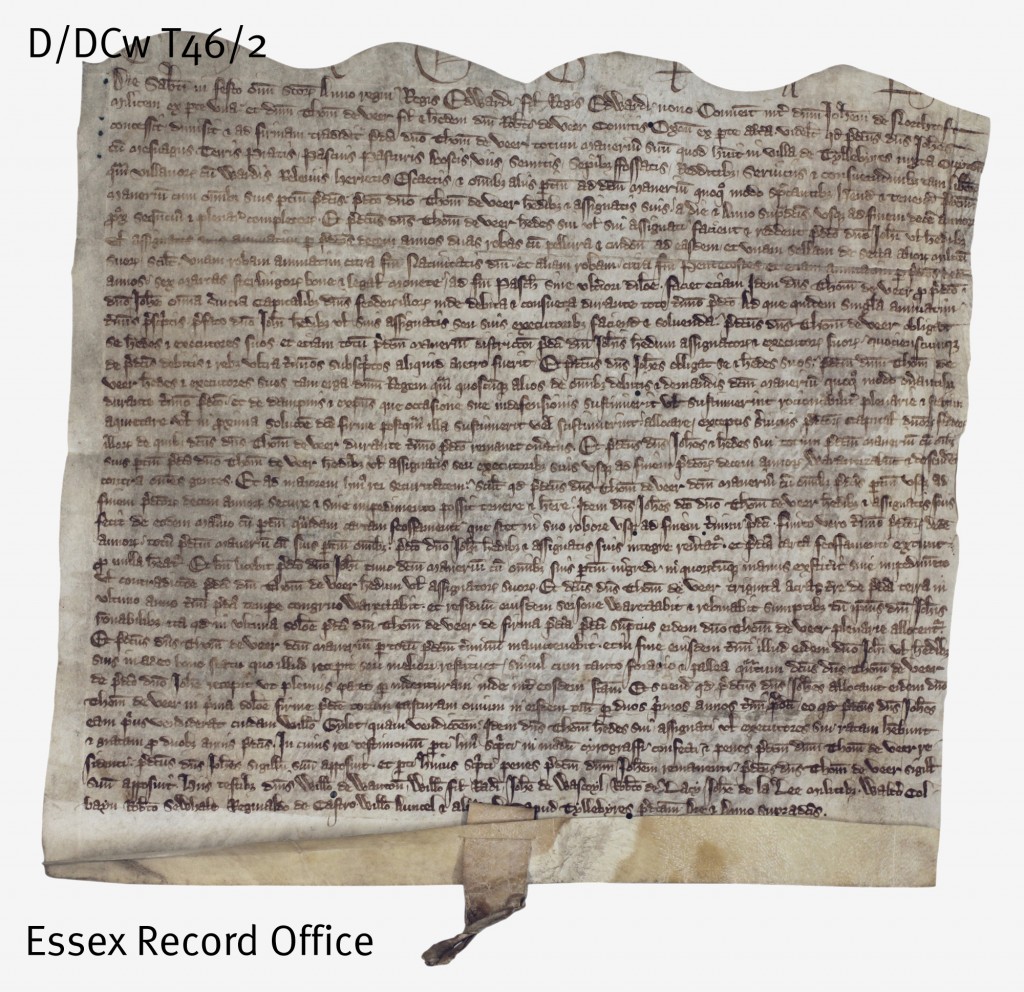

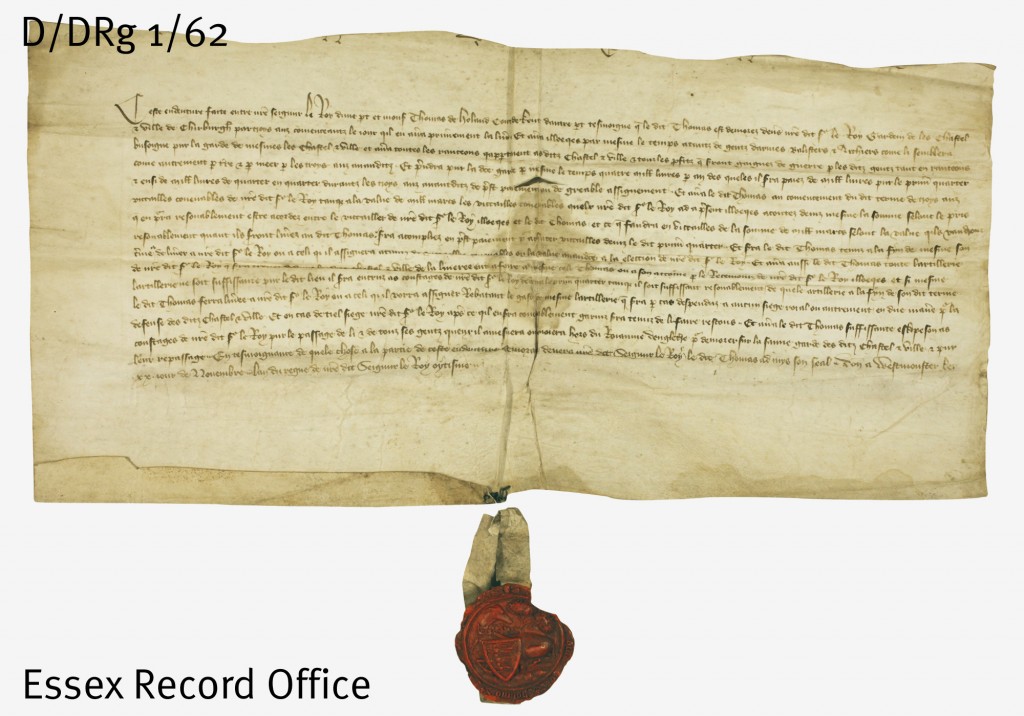

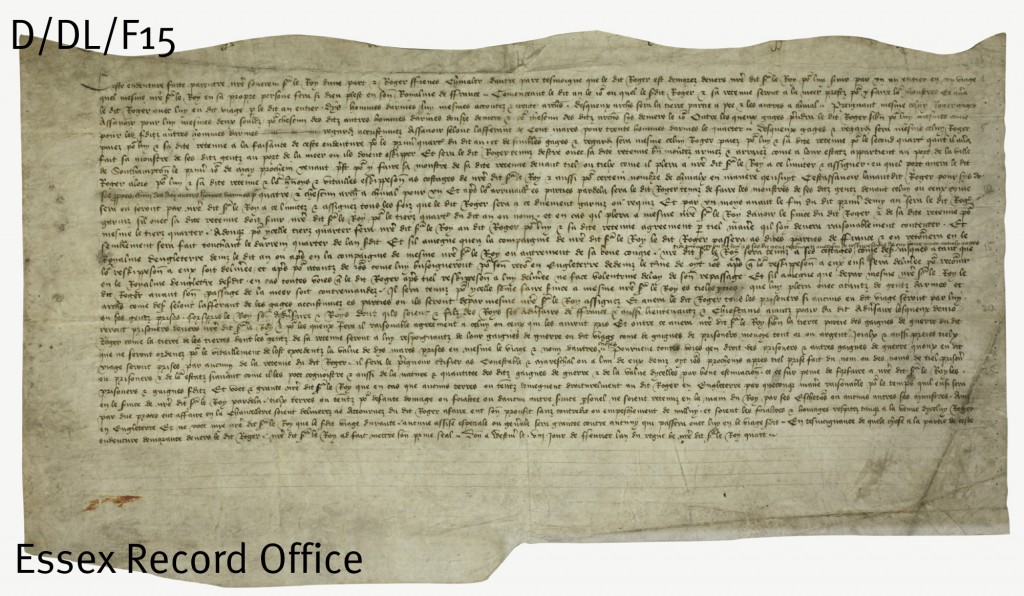

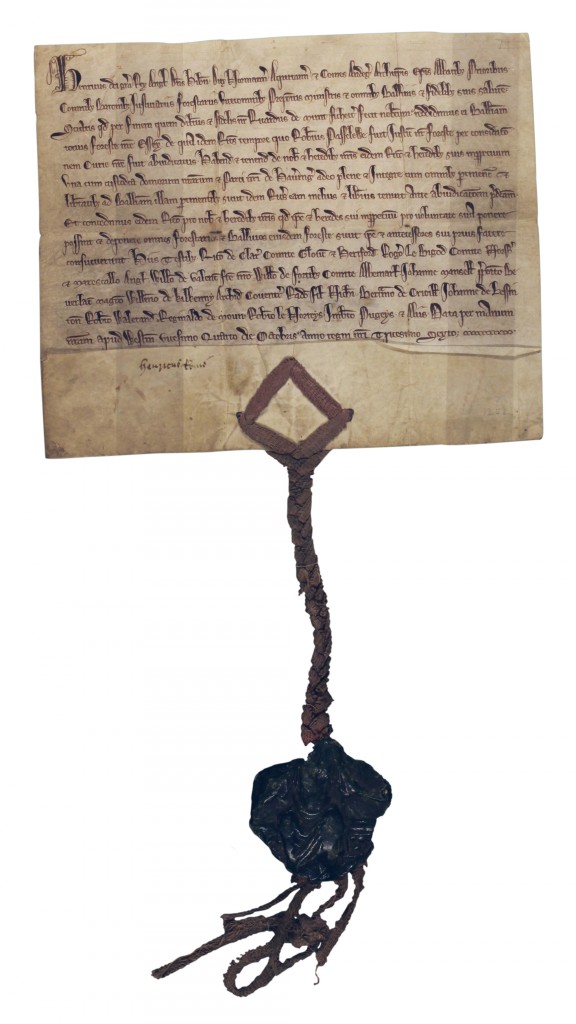

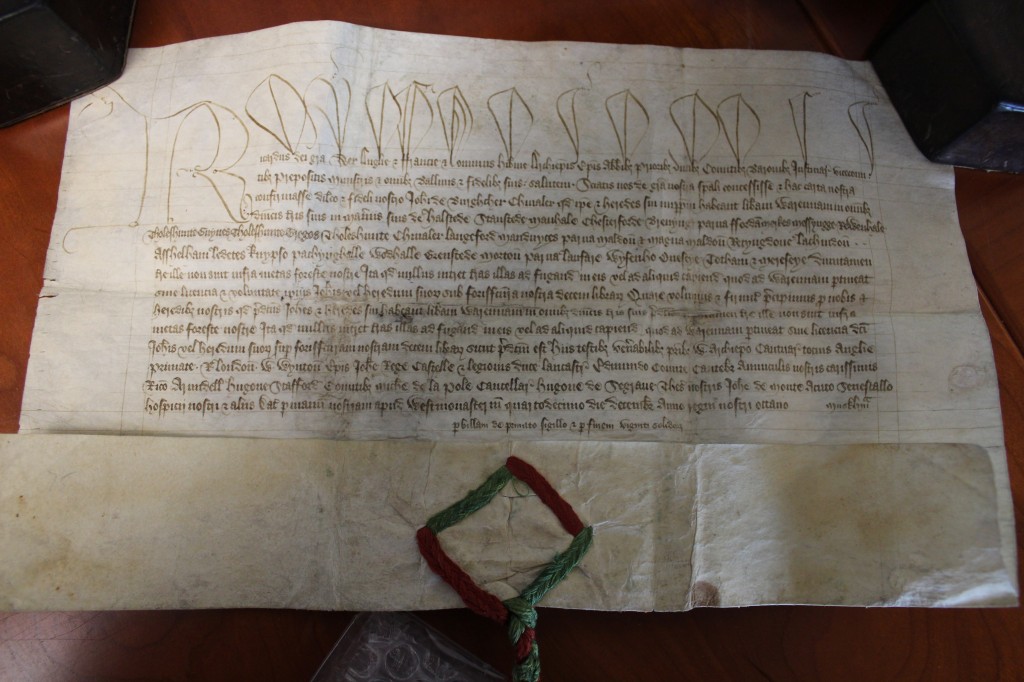

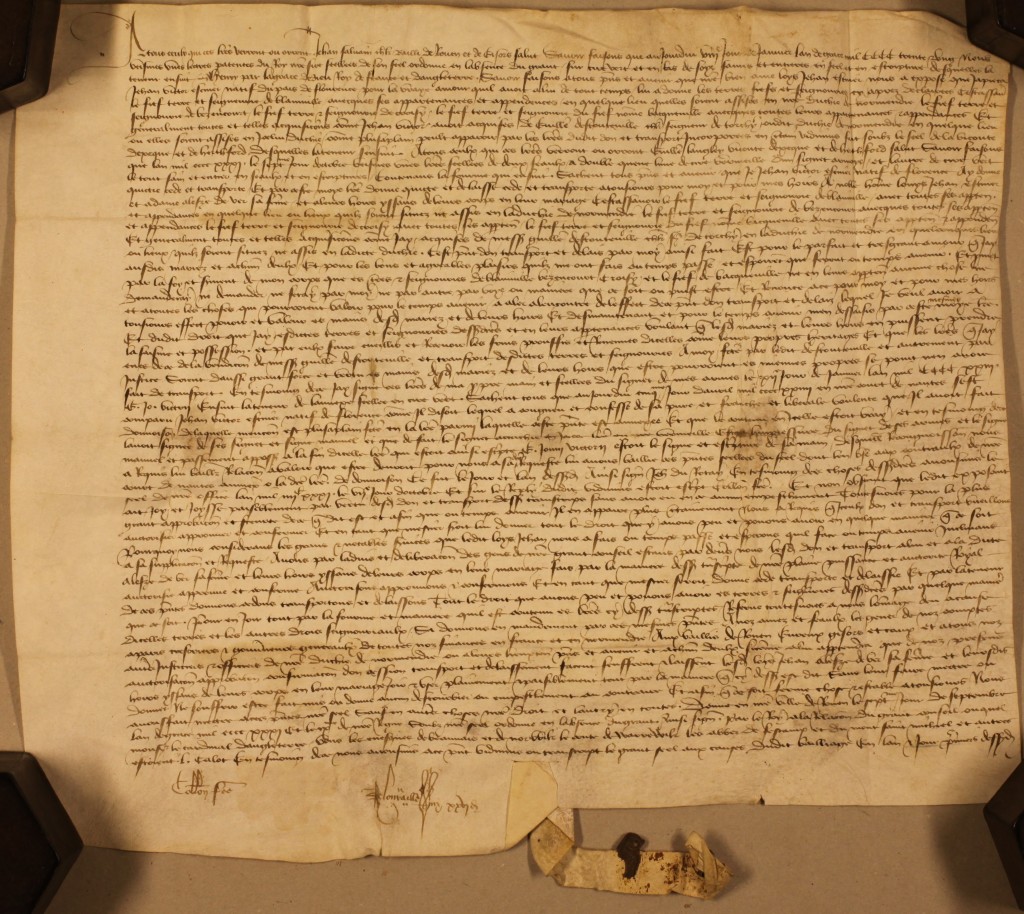

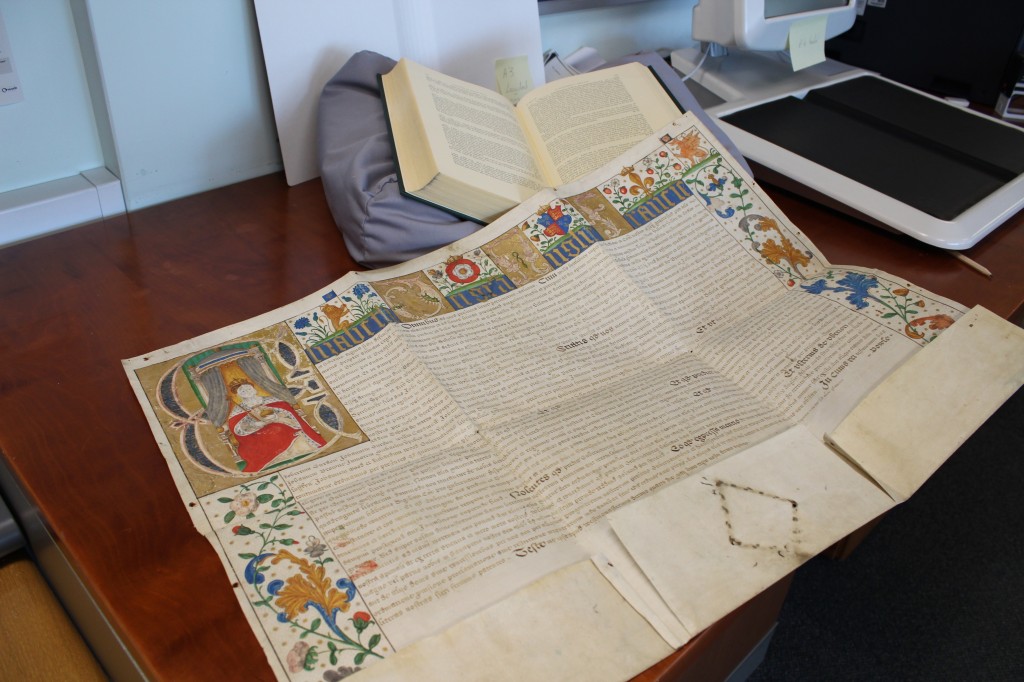

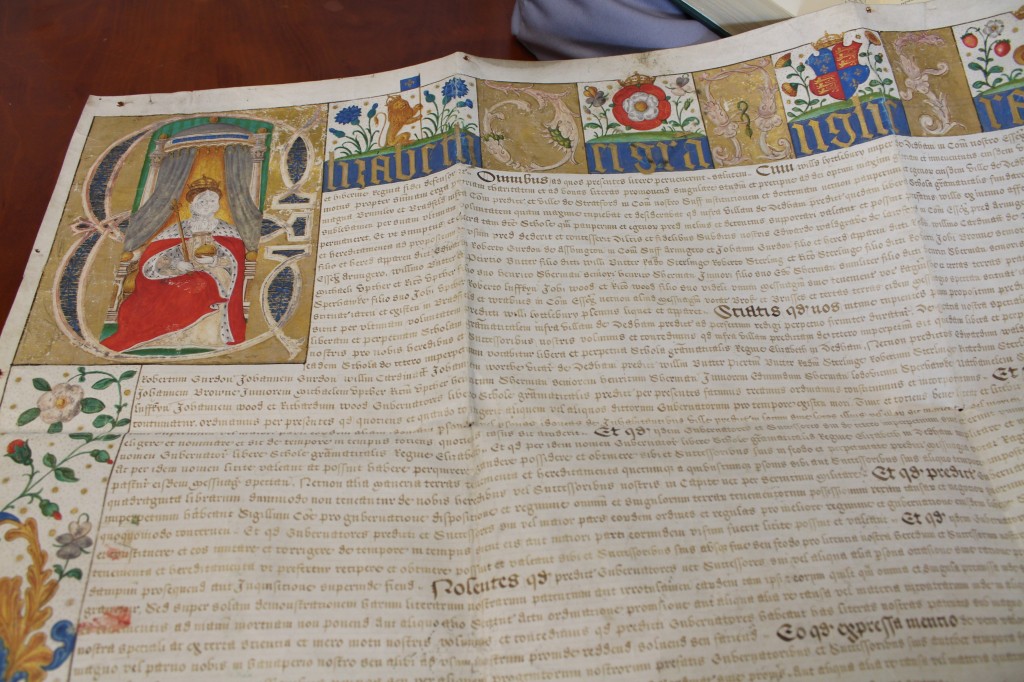

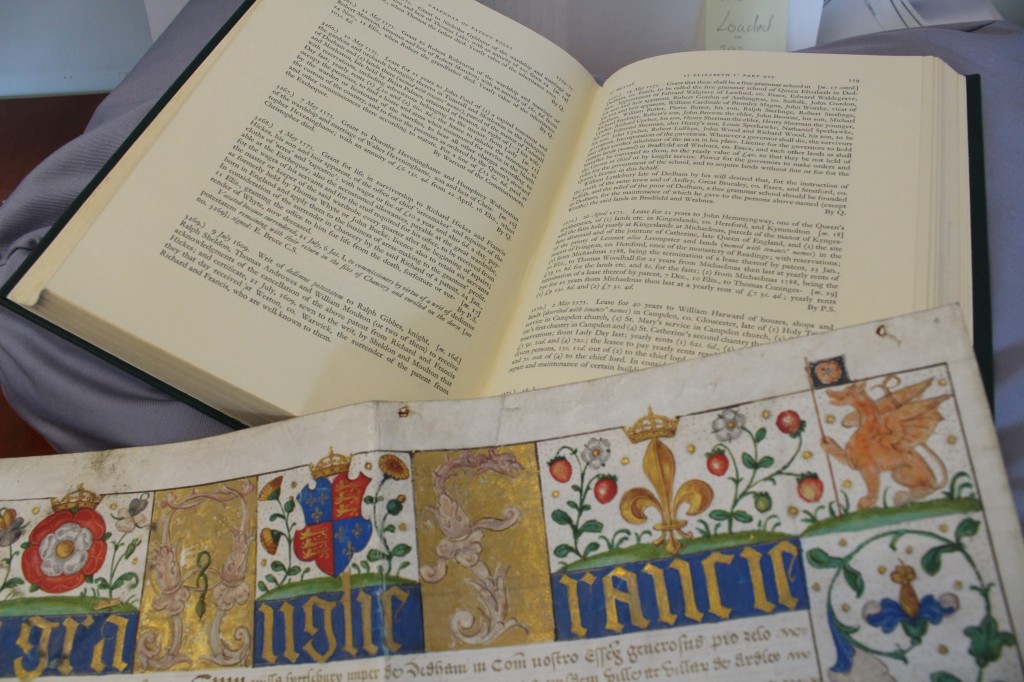

In 1922 the British Library acquired most of the muniments of the Capells, Earls of Essex, from their estate at Cassiobury Park. The Cassiobury Papers include collections of documents from many manors in Essex. Among these are extensive document collections from Porters Hall and Stebbing Hall, the two principal manors in the parish of Stebbing, acquired by the Capells in 1481 and 1546 respectively.

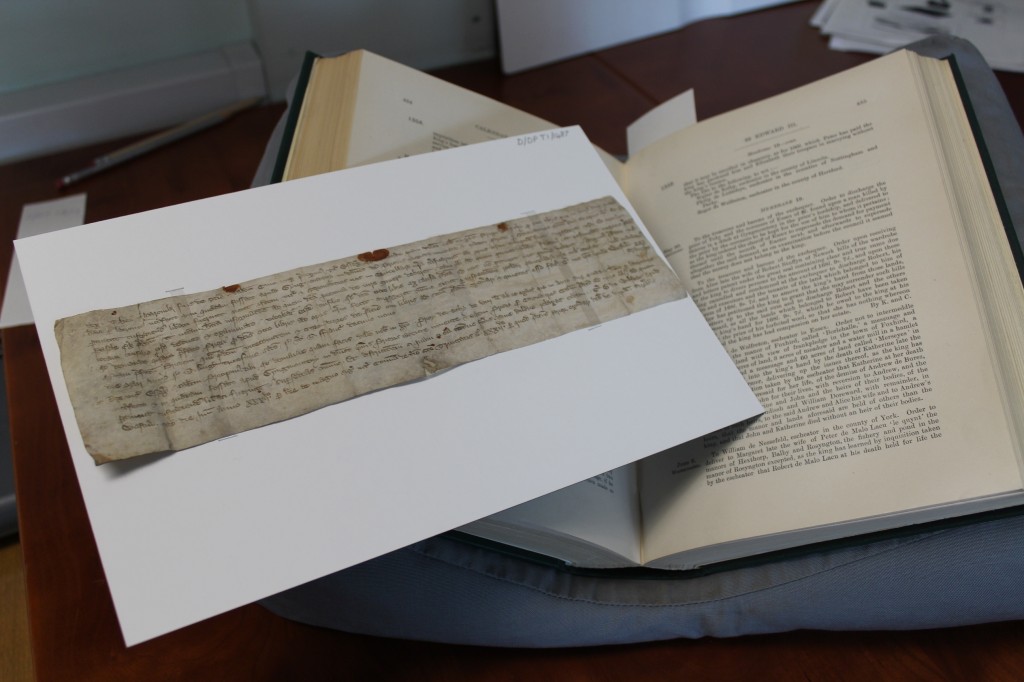

Neither of the published guides to the Cassiobury Papers – the Historical Manuscripts Commission’s Report on Manuscripts in Various Collections, vol. vii, and the British Museum’s Catalogue of Additions to the Manuscripts, 1921-1925 – contains much more than summary descriptions of the collection. It has taken several trips to the U.K. and significant time in the B.L. Manuscripts Room to begin to appreciate the possibilities of the records for a reconstruction of late-medieval and Tudor Stebbing. How appropriate that I should have the opportunity to talk about them as part of an event honouring the Manorial Documents Register and its dedication to making manorial collections more accessible to historians!

I had worked briefly with Stebbing’s manorial records years ago as part of the research for a book, A rural society after the Black Death: Essex 1350-1525. My re-acquaintance with those records is a story in its own right: two years ago I received an email out of the blue from Graham Jolliffe, Chairman of the Stebbing Local History Society, who had seen my references in A rural society to Stebbing documents and enquired politely whether I had any translations of the texts of them that I could share. The answer was no, then. But as we continued to chat I realised this was a chance for a worthwhile project.

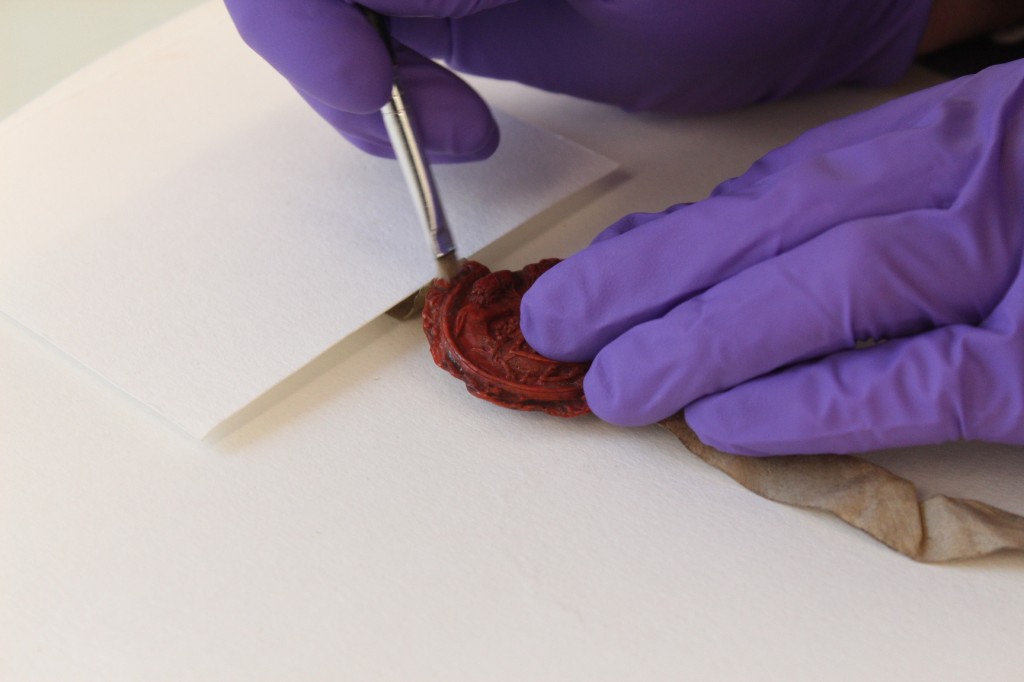

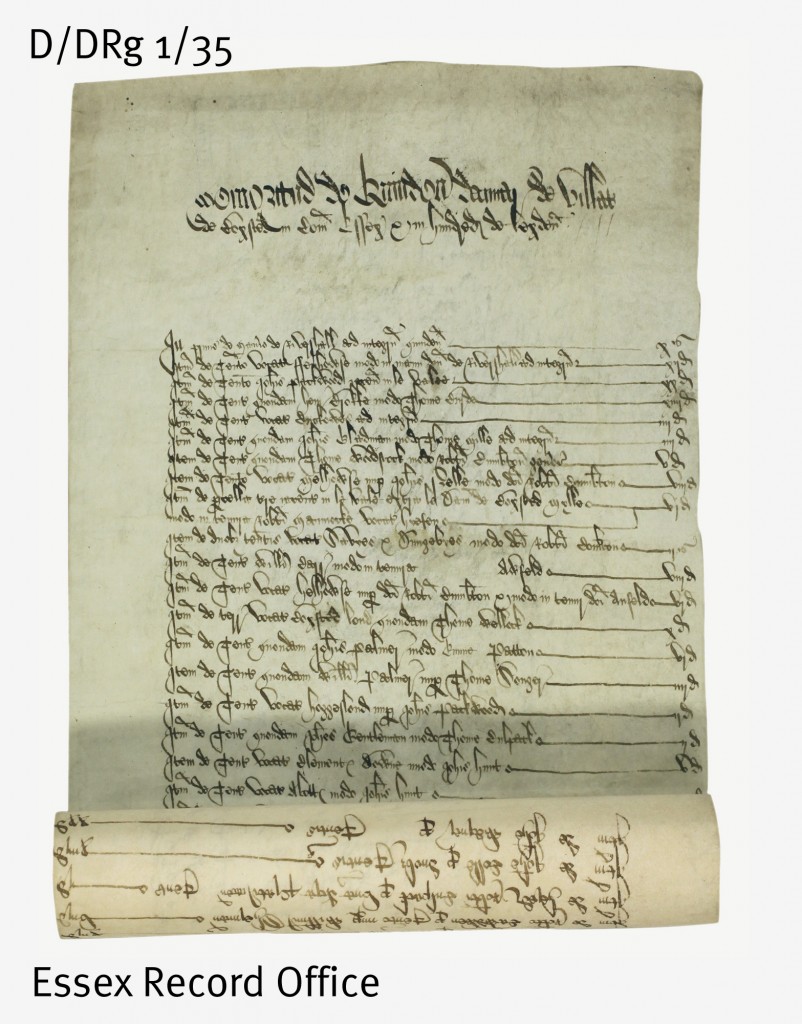

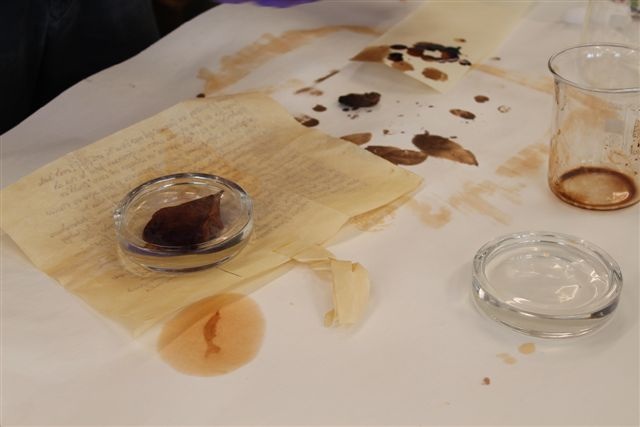

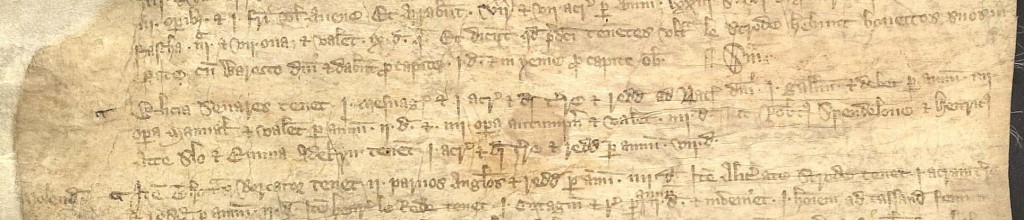

The Stebbing records are not rich in manorial court rolls and even less so in manorial accounts. However, they are exceptionally rich in surveys, rentals, and other records setting out the landholding patterns of Porters Hall and Stebbing Hall from the late thirteenth into the seventeenth century. In addition, the collection includes some remarkable records that are not typical of manorial documentation and in some cases pertain to the parish as opposed to the manor.

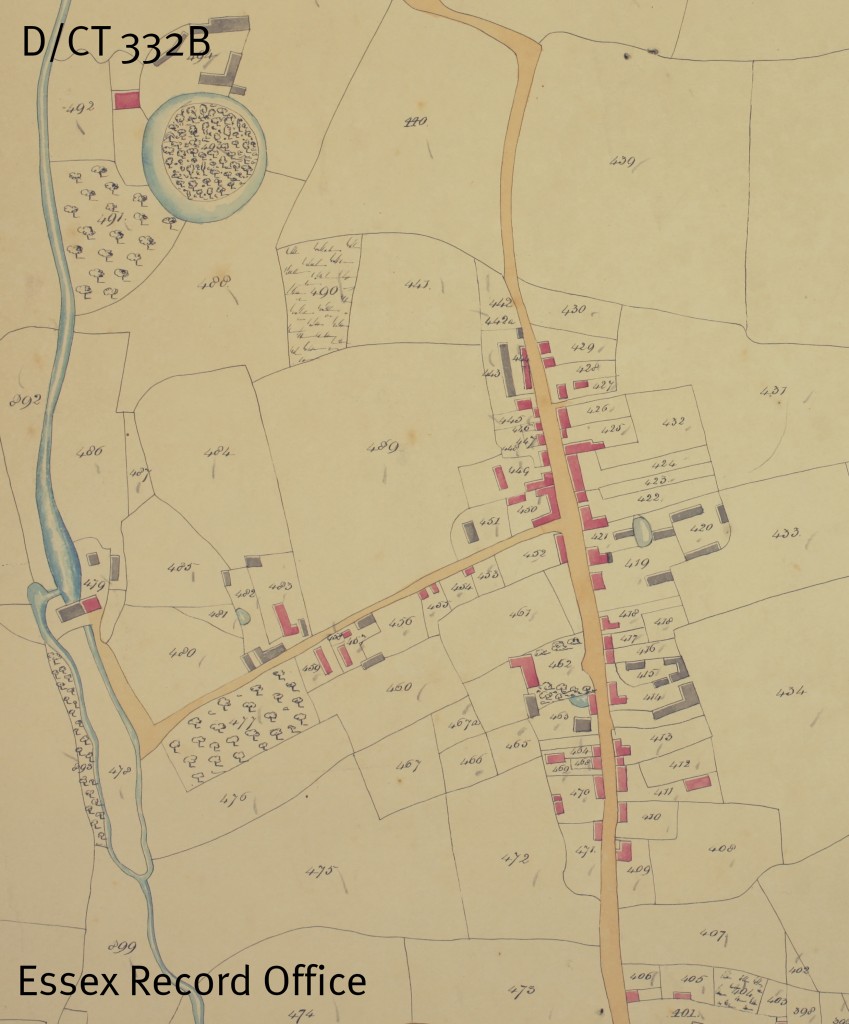

Combining and cross-referencing the Stebbing manorial and parish records have set in motion several lines of investigation. These include: Stebbing’s involvement in the 1381 revolt – which appears to have been previously unknown – and the backgrounds of some of its participants; a remarkable farmer’s account for the year (1482-1483) after William Capell acquired Porters Hall, and the detailed view it affords of local trading networks; the very rare survival of an assessment roll for parishioners’ contributions to wax money for the parish church and the glimpse this affords into the parish community and economy. The main Stebbing project currently underway is editing and translating for publication the series of land surveys and rentals, and – in collaboration with Graham Jolliffe and with an American colleague who is an expert in GIS (Geographical Information Systems) – to create a computer map of Stebbing and its tenancies. ‘Essex through the ages’ will be the first opportunity to present these projects to an audience.

Join us to hear more from Prof. Poos about this fascinating project at Essex through the ages: tracing the past using manorial documents on Saturday 12 July 2014. There are more details, including how to book, here.