On Monday 11th November 1918, news that an armistice had been agreed and that the fighting would cease at 11am that day spread through Essex. After over four years of sacrifice and slaughter, how did people react to the news that the war was finally coming to an end?

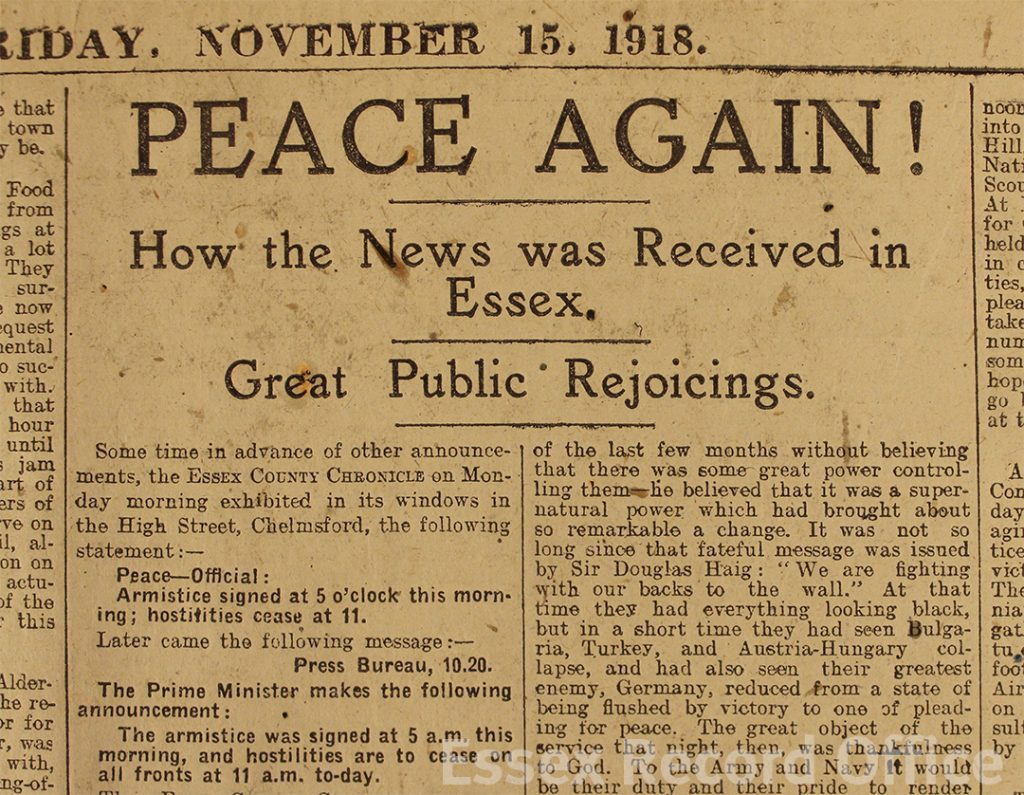

The Essex County Chronicle reported on the Armistice on 16th November 1918

The news was announced in various ways; in Chelmsford the Essex County Chronicle exhibited a notice in their office window:

‘Peace – Official:

Armistice signed at 5 o’clock this morning; hostilities cease at 11.’

Factories sounded their hooters and whistles, church bells rang out, and the drivers of railway engines sounded their whistles. According to reports in the Essex County Chronicle of 16th November 1918, within a short time most towns were ablaze with flags and bunting, and the streets crowded with people. In Braintree, for example, ‘all work ceased and joyous scenes began’. (In Bishop Stortford, it was reported that a good trade had been done in flags and bunting over the weekend in anticipation of the good news.)

The day was declared a holiday; in Chelmsford, ‘Hoffmann’s great works emptied themselves of the thousands of workpeople’, while in Braintree ‘girl and men workers’ from Crittall’s and Lake and Elliot’s works flooded out. In Dagenham, the managing director of the Sterling Telephone and Electric Company, Mr Guy Burney, was the one to break the news to the workers. The factory staff sang the National Anthem and Rule Britannia, and had a ‘short impromptu dance’.

Across the county, high streets and market squares were filled with people, impromptu speeches were made, and bands played patriotic songs, hymns, and the National Anthem. In Chelmsford, reported the Chronicle, ‘Soldiers and civilians shook each other by the hand, and everyone wanted to laugh, cheer, and shed a tear of gladness at the same time’.

In Witham, a procession paraded the streets composed of women workers from a local munitions workshop, and Scottish soldiers billeted in the town, ‘carrying a large Union Jack and singing joyfully’.

In Halstead, alongside celebrations in the streets, 21 shots were fired from a cannon at Halstead Brewery by one of the owners, Lt. Adams, who also held a commission in the Naval Volunteer Reserve.

In Romford, music was provided in the afternoon by the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Band, who were stationed nearby. There was no military band in Writtle, but recovering wounded men paraded ‘with a tin kettle and bath band’.

In Dagenham, a spontaneous football match was arranged between the RAF based at Sutton’s Farm, and workers from the Sterling factory; the result was a 4-2 win for the factory side.

In Doddinghurst things were a bit more sedate; a whist drive was held in the afternoon to raise money for prisoners of war.

In many places the Christian religion played a central role on Armistice Day, with most churches holding services of thanksgiving in the evening. Vicars spoke to very large congregations; at Chelmsford Cathedral people spilled out into the porch and outside. The central theme of the sermons reported in the Chronicle was giving thanks to God for the Allied victory. One vicar in Brentwood spoke of how he believed that ‘a supernatural power’ had brought about the Victory, and gave thanks for ‘what was to be, they believed, a permanent peace’.

Celebrations continued into the evening (troops in a camp near Bishop Stortford were told by their commander that they would be allowed out until the heady hour of 11pm). In Braintree, the evening brought a concert, arranged by discharged soldiers, held in the Institute Hall. In Bishop Stortford, a large number of people were still gathered in the market square, and local Volunteers paraded, with light being provided by the Fire Brigade carrying torches, and the parade being joined by soldiers, women workers, wounded, and school children. ‘Most of the lamps in the streets had been lighted, and welcome lights again shone from windows.’

Celebrations in Witham were a little different; at 10pm, ‘a great bonfire was lit in the old Market Place in the middle of Witham High Street. Tar barrels, with a quantity of tar, boxes, timber, and other fuel were provided, and a great flare was created, reaching as high as the tops of houses adjoining the street. A crown of many hundred people, soldiers, sailors, munition girls, and townspeople, assembled round the fire, dancing, singing patriotic songs, and generally enjoying themselves. The fire, which lasted four hours, was the greatest seen for many years in Witham Street, where on previous historic occasions such fires were lighted’. The townspeople enjoyed the bonfire so much, they had another one the following night on the green opposite the church, this time with fireworks, while patriotic songs were sung and the church bells pealed.

In Bures the occasion was also marked with a bonfire, the villagers going as far as to burn an effigy of the Kaiser ‘amid loud shouts of approval’.

In Dunmow, meanwhile, German prisoners of war accommodated in the town workhouse also welcomed the news with a smoking concert in the evening. The end of the war ‘gave them obvious pleasure, as did the turn events had taken regarding the Kaiser’. The over 200 Germans sang German songs ‘for some hours’, and apparently many ‘expressed the hope that they would not be compelled to go back to Germany, but allowed to stay at their present employment in England’.

Some towns continued the celebration over the following days. In Braintree, factories remained closed on Tuesday, and ‘processions paraded the town all day, headed by the ugle bands of the Cadets and Boy Scouts, and the newly formed Brass Band’ (which had got together the previous day). In Halstead, a service of thanksgiving was held in the Town Hall on Wednesday, with people coming from all the town’s places of worship. The service finished on Market Hill, and bells of nearby St Andrew’s church rang out, the tower being decorated with national flags and bunting

Alongside the celebrations though, people also remembered those they had lost. In Braintree, amid ‘all the rejoicing people could be seen weeping for their relatives who had made the supreme sacrifice, and generally the gladness manifested was tinged with sorrow for the fallen.’