Today we bring you some more industrial treasures from the archive in the run up to our special one-day conference on Essex’s Industrial Archaeology on Saturday 6 July. Tickets are £15 and can be booked by telephoning 01245 244614. Details on our speakers and their topics can be found here.

In order to attract – and keep – workers, many employers decided to build housing for their workers. Some built the cheapest, most basic housing possible, but others had a genuine concern for their workers’ welfare and built good quality homes, appreciating that healthy, content workers would be more loyal and productive. Most such houses were built after industrialisation had firmly taken hold in the mid-late nineteenth century, but there are also earlier and later examples of such developments, on varying scales.

Tony Crosby will be talking about industrial house from sites all around the county at Essex’s Industrial Archaeology, but here we share with you just a few examples, from Bentall’s in Heybridge, Crittall’s in Silver End, and Bata in East Tilbury.

E.H. Bentall & Co. of Heybridge

E.H. Bentall & Co. were ironfounders and agricultural implement makers based in Heybridge, who in the early twentieth century also dabbled with the internal combustion engine and car manufacturing. Bentall’s sold agricultural machinery all over the country and all over the world, such as this chaffcutter which ended up in Australia. By 1914 the company employed 6-700 people.

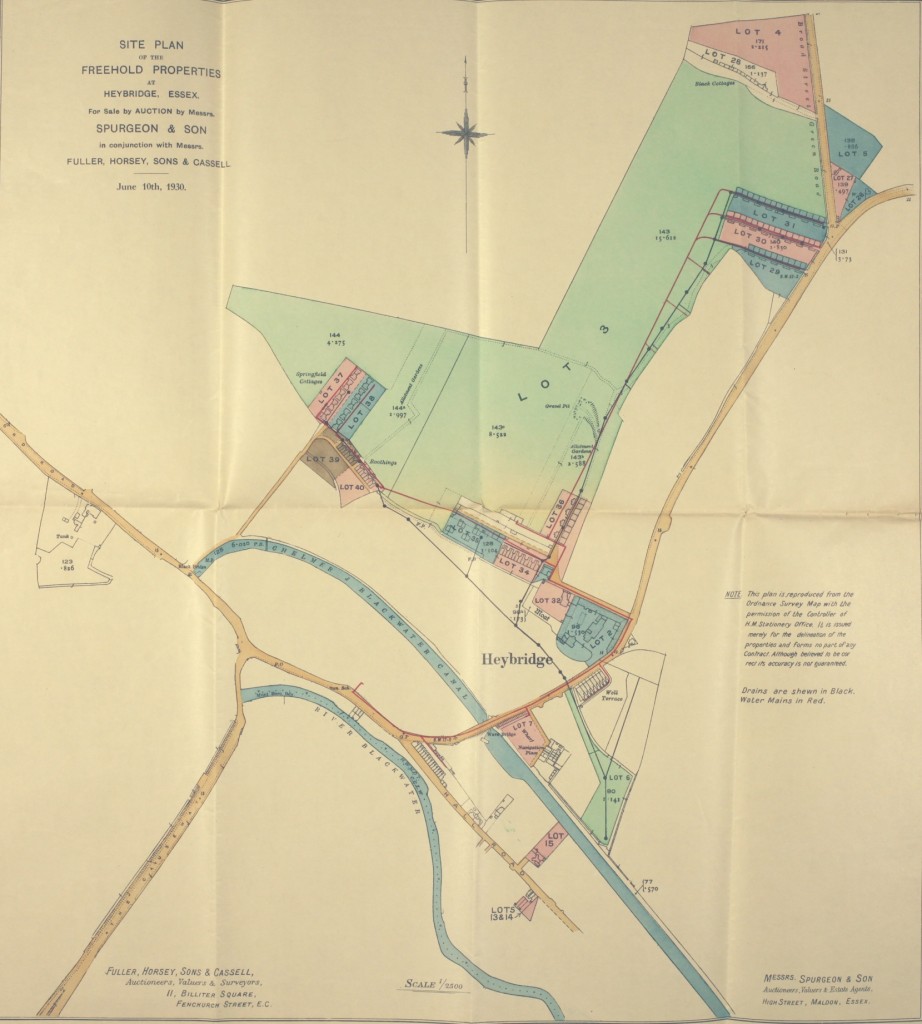

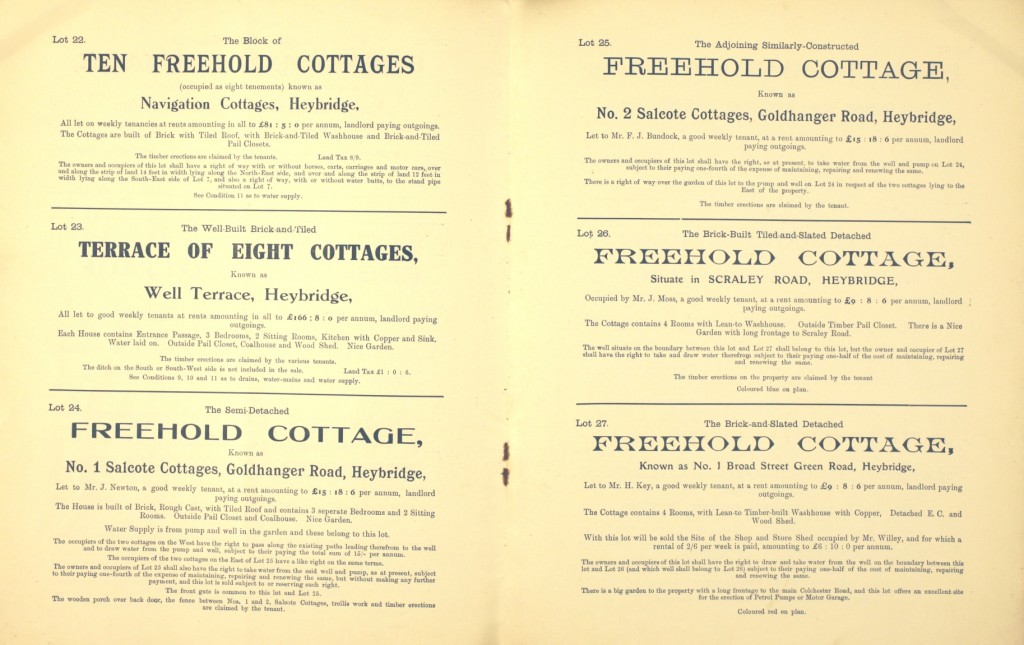

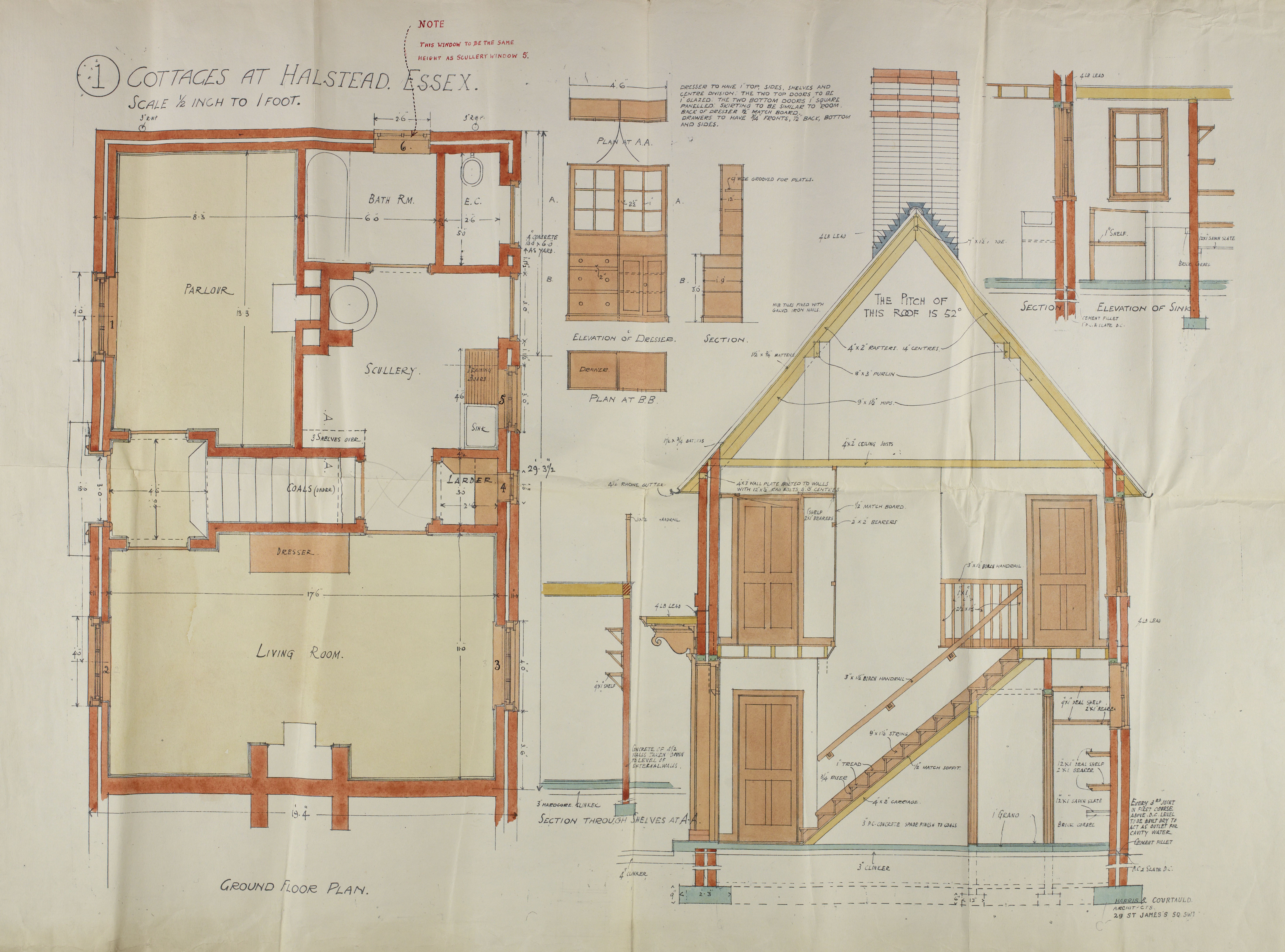

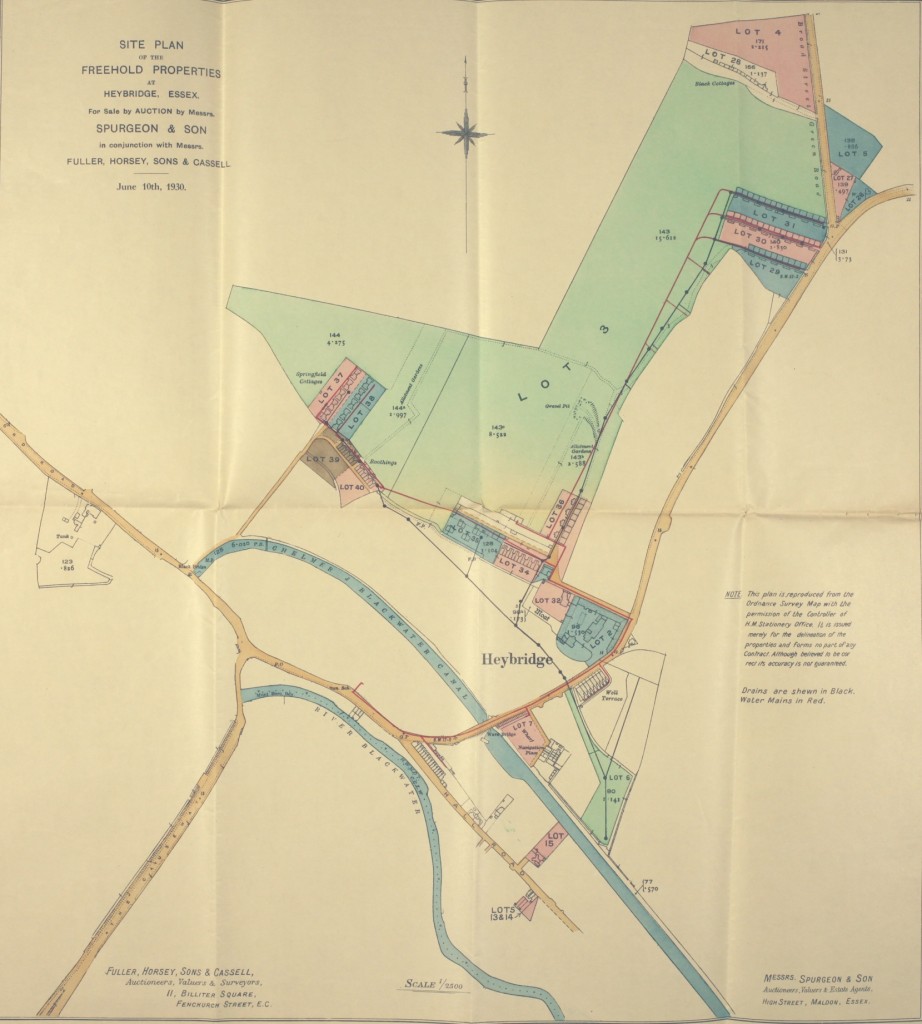

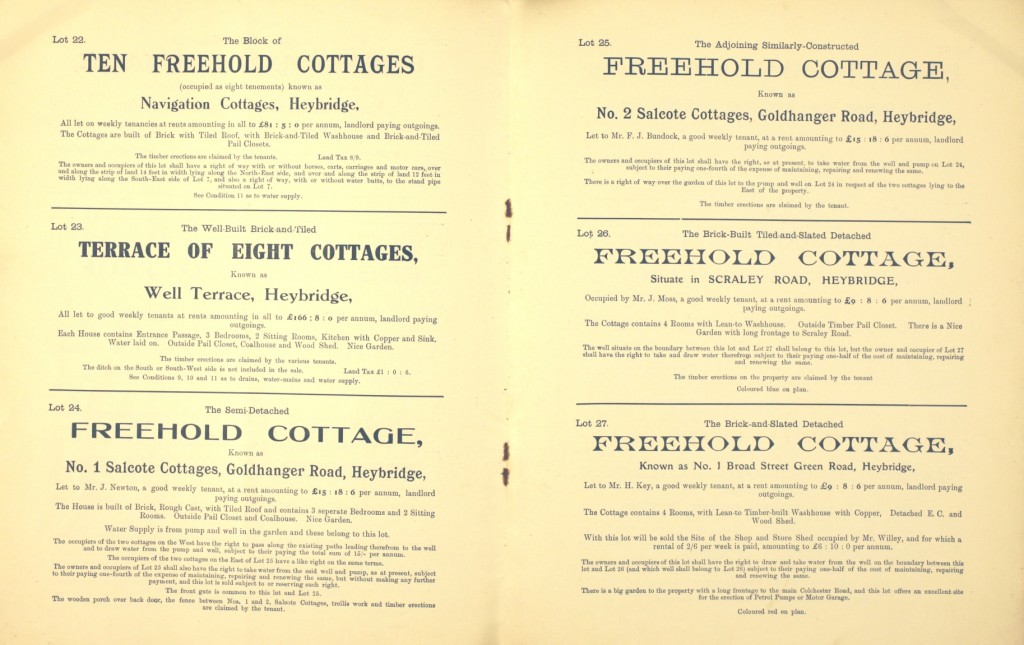

Bentall’s began building housing for their workers in the mid-late 1800s, with houses reflecting the social status of different levels of employees. The eight two-storey cottages built at Well Terrace were let to supervisors, and as such had a higher level of architectural detail than other developments. In the sale catalogue below, they are described as each containing: ‘Entrance Passage, 3 Bedrooms, 2 Sitting Rooms, Kitchen with Copper and Sink, Water laid on. Outside Pail Closet, Coalhouse and Wood Shed. Nice Garden.’ Well Terrace can be found on the map below, just to the north-east of the wharf.

Twelve three-storey houses were built in Stock Terrace for employees with large families, although some were set aside for younger single employees, subject to the supervision of a landlady. Two terraces of eight cottages called The Roothings were also built with minimum detailing for basic grade foundry workers (lot 40 on the map below). Bentall’s building became quite experimental, and in 1873 three terraces of single-storey flat-roofed concrete cottages were built, called Woodfield Cottages, although the roofs were later pitched following water leaks. More of these houses were built at Barnfield Cottages in the early twentieth century, along with several semi-detached Arts and Crafts style houses for managers.

In 1930 Bentall’s sold off a huge amount of housing stock, all with ‘good weekly tenants’, and the sale catalogue and accompanying plan (D/DCf B839) show us the extent of the housing Bentall’s had built up for their employees. The company had hit hard times in the late 1920s and 1930s, which could perhaps explain why they sold off so much property, but they did eventually recover and prosper again.

Plan showing properties sold by Bentall’s in 1930 (D/DCf B839) (Click for a larger version)

Extract from sale catalogue showing just a few of the properties sold by Bentall’s in 1930 (D/DCf B839)

Crittall Manufacturing Company, Silver End

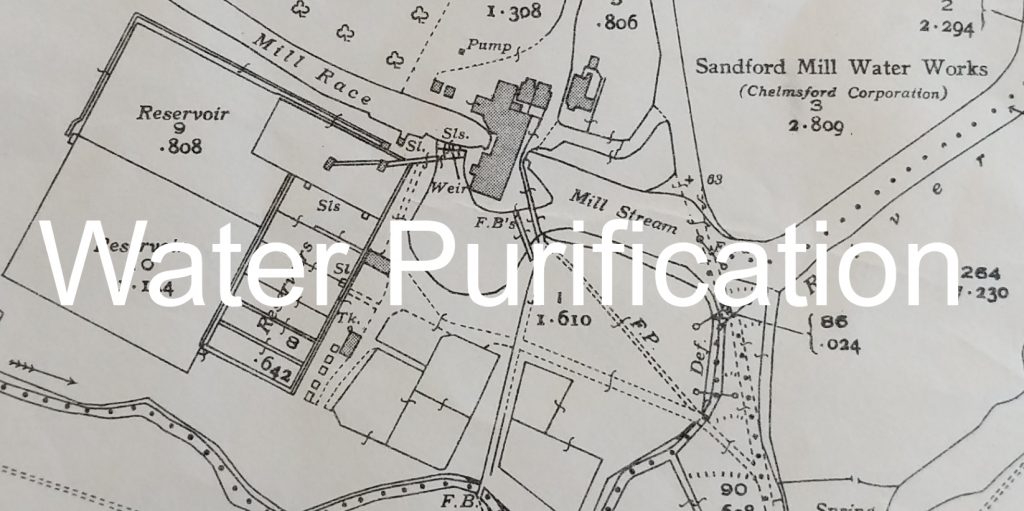

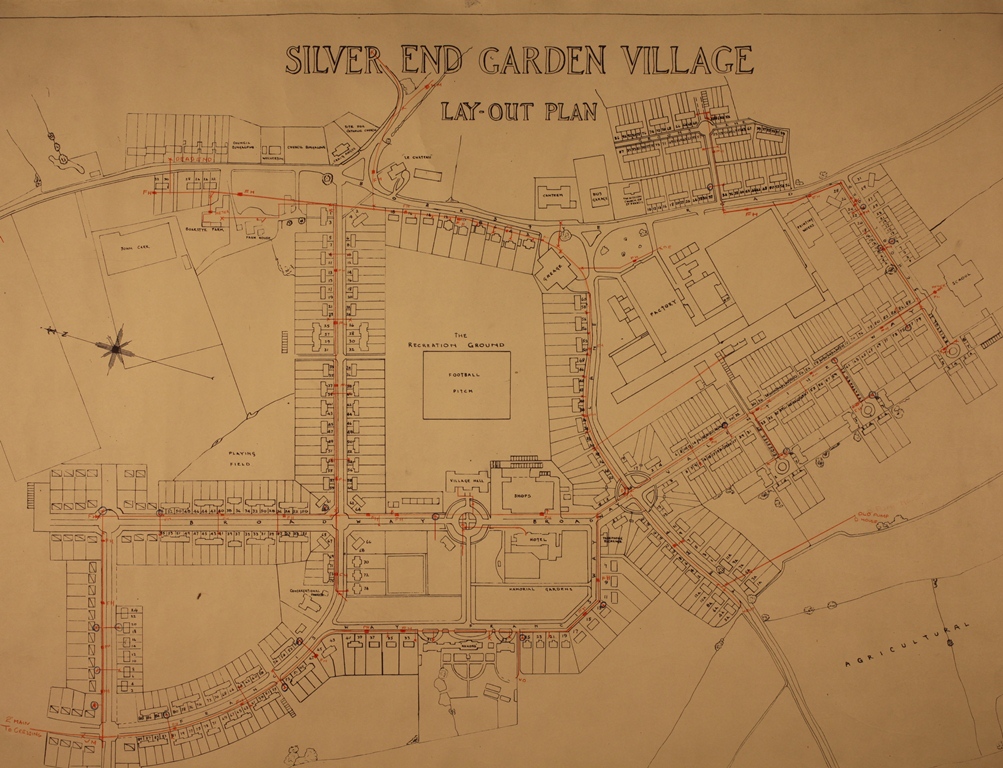

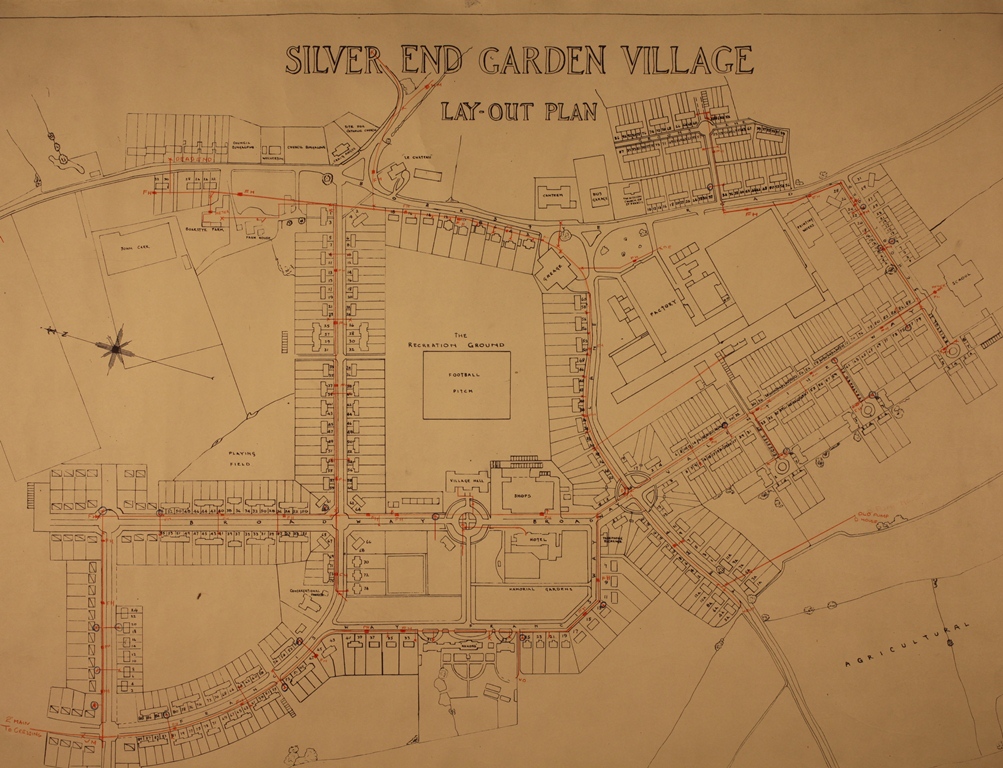

Silver End village plan (D/DU 1656/1)

This plan for Silver End shows the development of housing for workers of Crittall’s, a metal window frame manufacturer. The development was conceived as a model village by Francis Henry Crittall, whose workforce had outgrown his existing factories in Braintree, Maldon and Witham. In the 1920s, he bought the land surrounding the tiny hamlet of Silver End, and built a new factory and a village surrounding it.

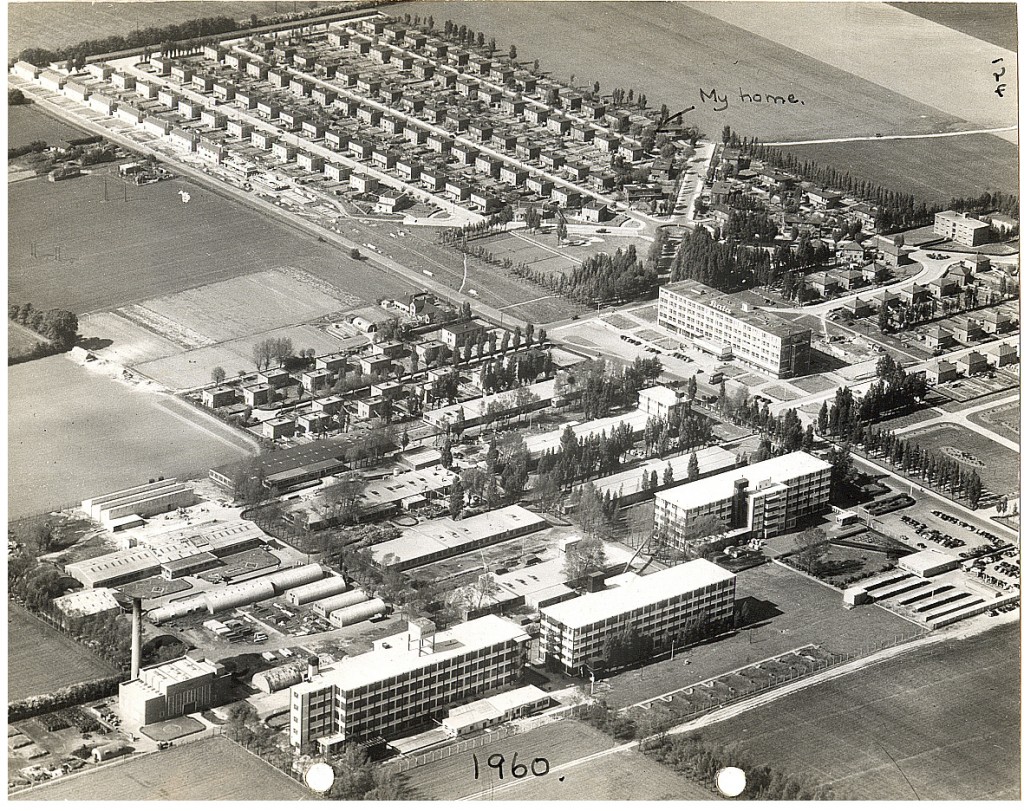

Aerial view of Silver End (I/Mp 290/1/1)

Crittall wanted his workforce to have comfortable, modern housing with hot running water and indoor bathrooms, and large outdoor spaces. The village also included a village hall, a dance floor, a cinema, a library, a snooker room and a health clinic. Crittall also purchased farmland surrounding the village so it could be as self-sufficient as possible and the price of food would be kept low.

Silver End was built in the tradition of enlightened employers providing ‘ideal’ environments for their workers, such as Titus Salt at Saltaire, and Cadbury at Bournville, and was also the first garden village in Essex.

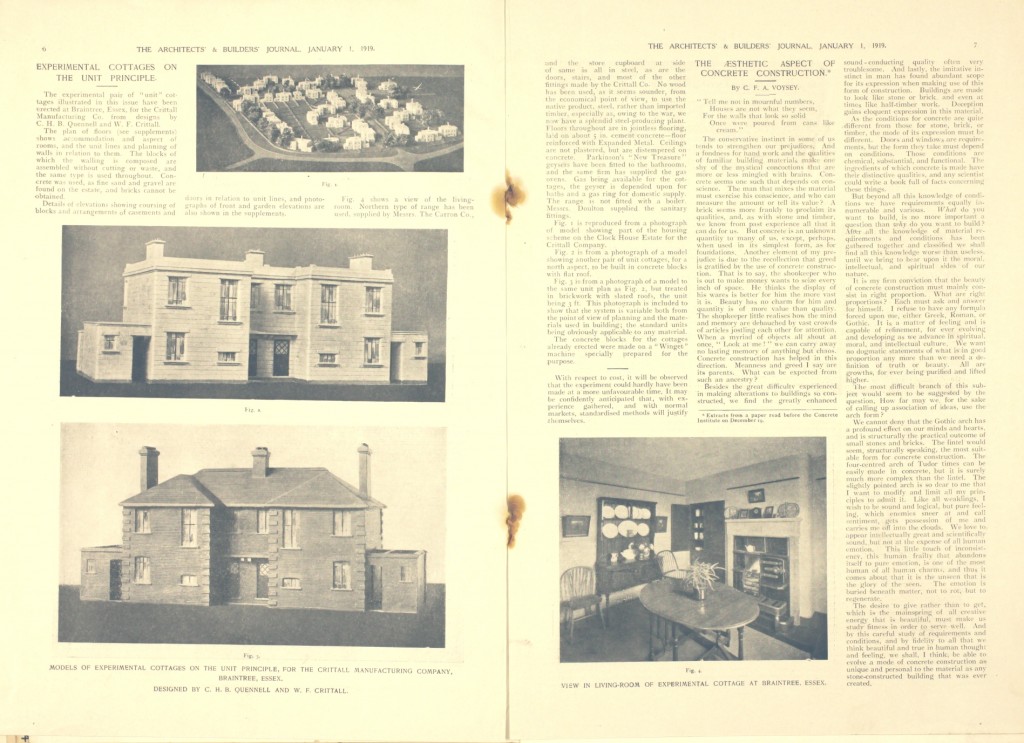

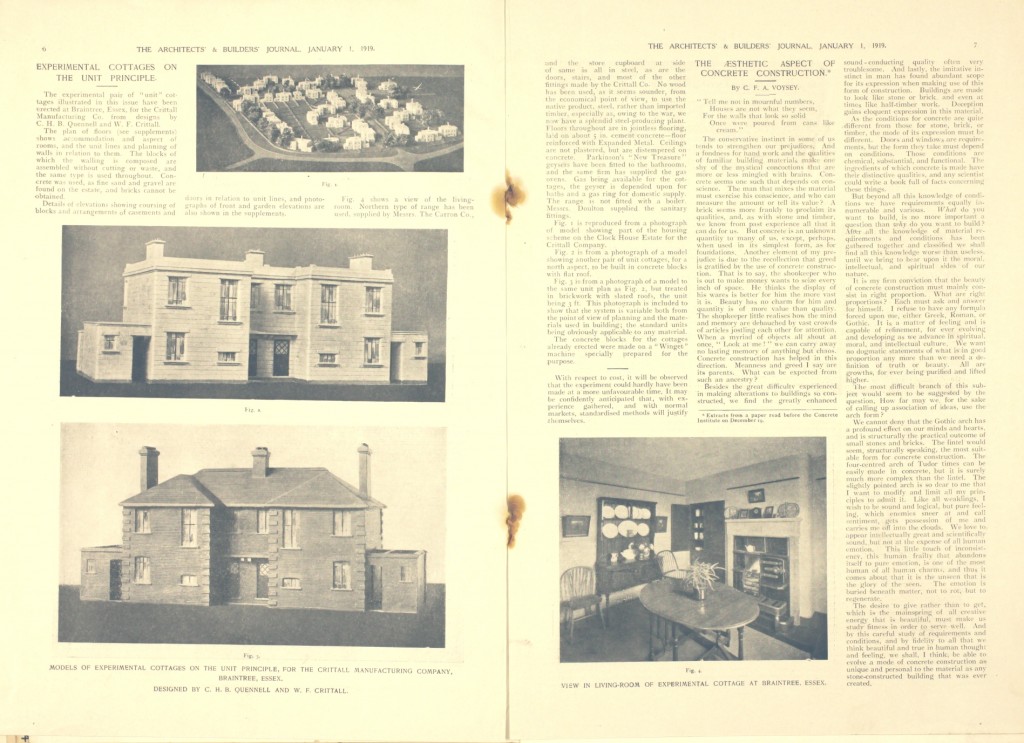

The development at Silver End employed innovative modernist architecture, and was written up in the Builders and Architects Journal in 1919 (D/Z 114/2)

The Bata Shoe Company, East Tilbury

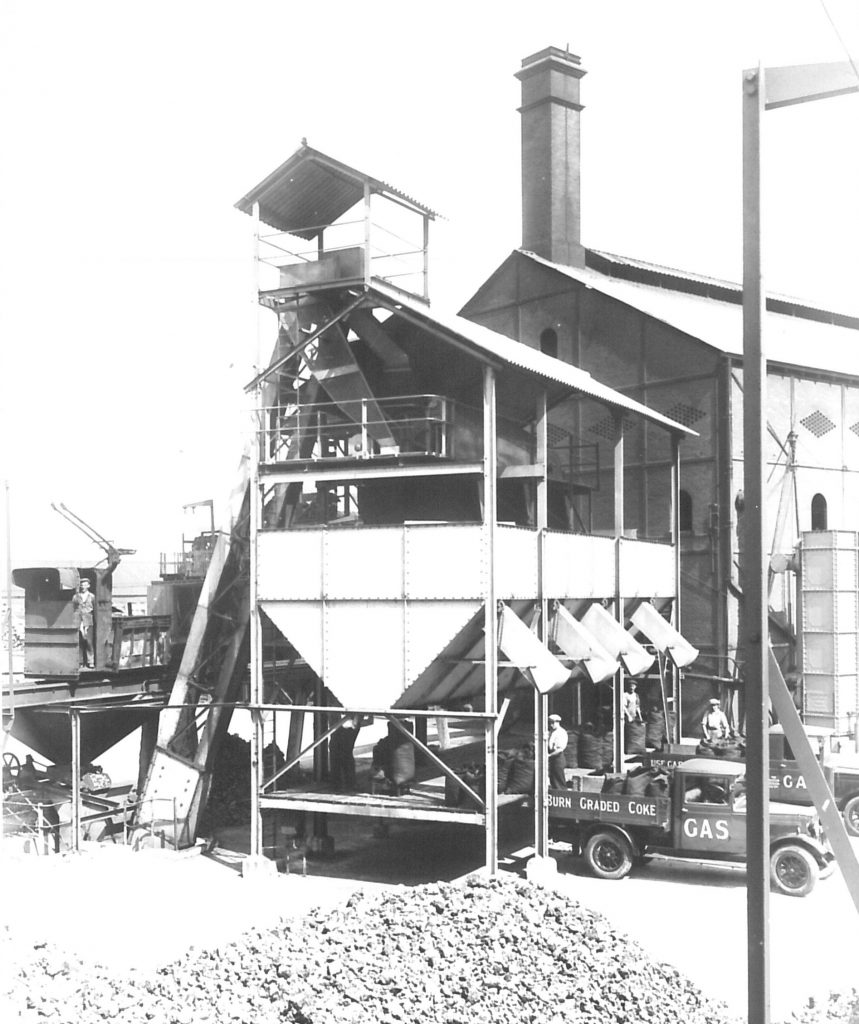

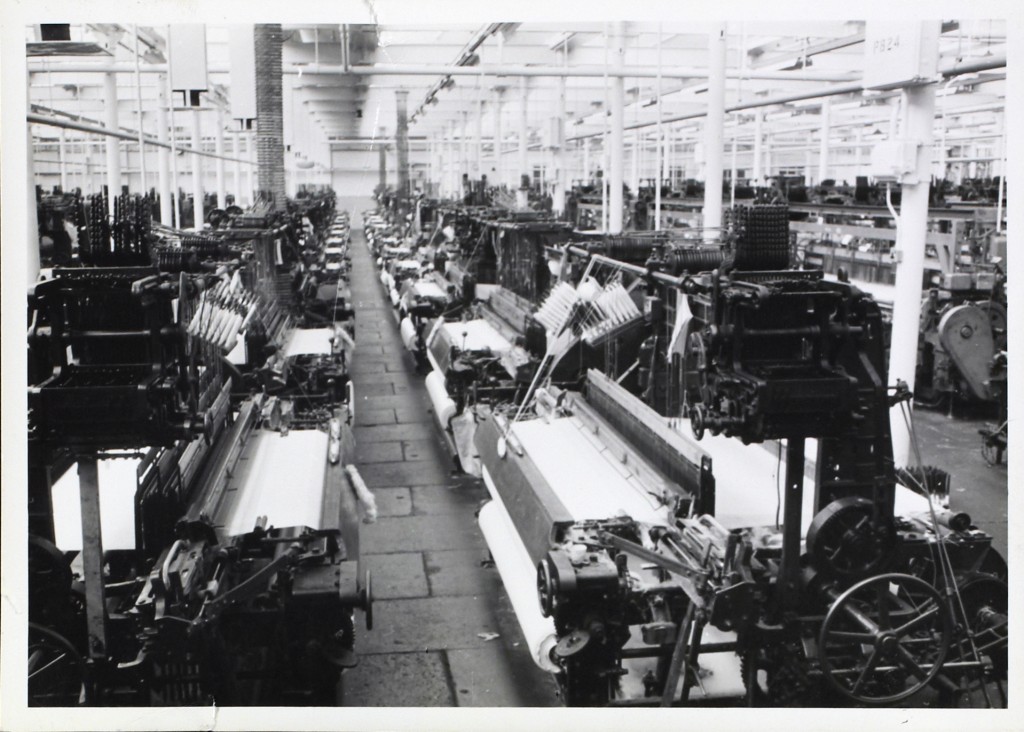

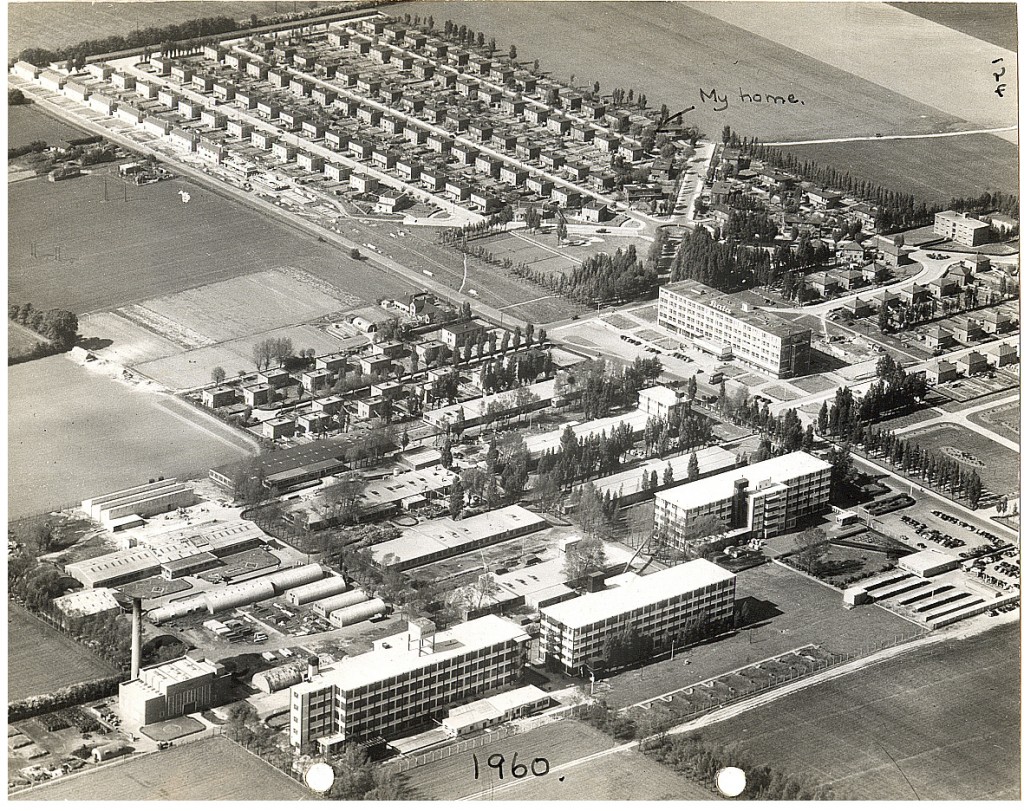

The Bata Shoe Company, founded by Tomas Bata in Czechoslovakia, opened a factory in the Essex marshes at East Tilbury in 1933. Over the following decades the company grew and eventually operated 300 shops across Britain and employed 3,000 people.

The Bata company built not only housing but educational and recreational facilities for their workers, and a real community grew around the factory. The Bata Reminiscence and Resource Centre is collecting the memories of the people who lived and worked at Bata and has built up a vast collection of artefacts and photographs, available to see at the Centre. You can find out more about them here.

Aerial photo of factory and estate c.1960 (Reproduced courtesy of the Bata Reminiscence and Resource Centre)

Bata Hotel, c.1937 (Reproduced courtesy of the Bata Reminiscence and Resource Centre)

Queen Elizabeth Avenue c.1971 (Reproduced courtesy of the Bata Reminiscence and Resource Centre)

Swimming pool on the Bata estate (Reproduced courtesy of the Bata Reminiscence and Resource Centre)

Essex’s Industrial Archaeology

Saturday 6 July 2013, 9.30am-4.30pm

Tickets £15 – please book in advance by telephoning 01245 244614

See here for more information