Ahead of the centenary of the end of the First World War, Archive Assistant Sarah Ensor tells us about one record of how Essex people remembered their lost loved ones. Discover more First World War stories of Essex people and places on Saturday 10th November 2018 at ‘Is this really the last night?’ Remembering the end of the First World War.

This month is the centenary of the end of hostilities of the Great War. To some the Armistice was a reason for joyous celebration, but for the many who had lost loved ones it was a time tinged with sadness. The ultimate sacrifice made by people throughout the conflict was marked in many ways such as on stone war memorials in villages and towns, on memorial boards in schools and councils, and on plaques in churches and businesses.

The Reverend Robert Travers Saulez had been rector at St. Christopher’s in Willingale Doe from 1906. He and his wife Margaret had four children, three sons and a daughter. Their sons were all educated at Felsted School and then joined the army, serving overseas during the Great War.

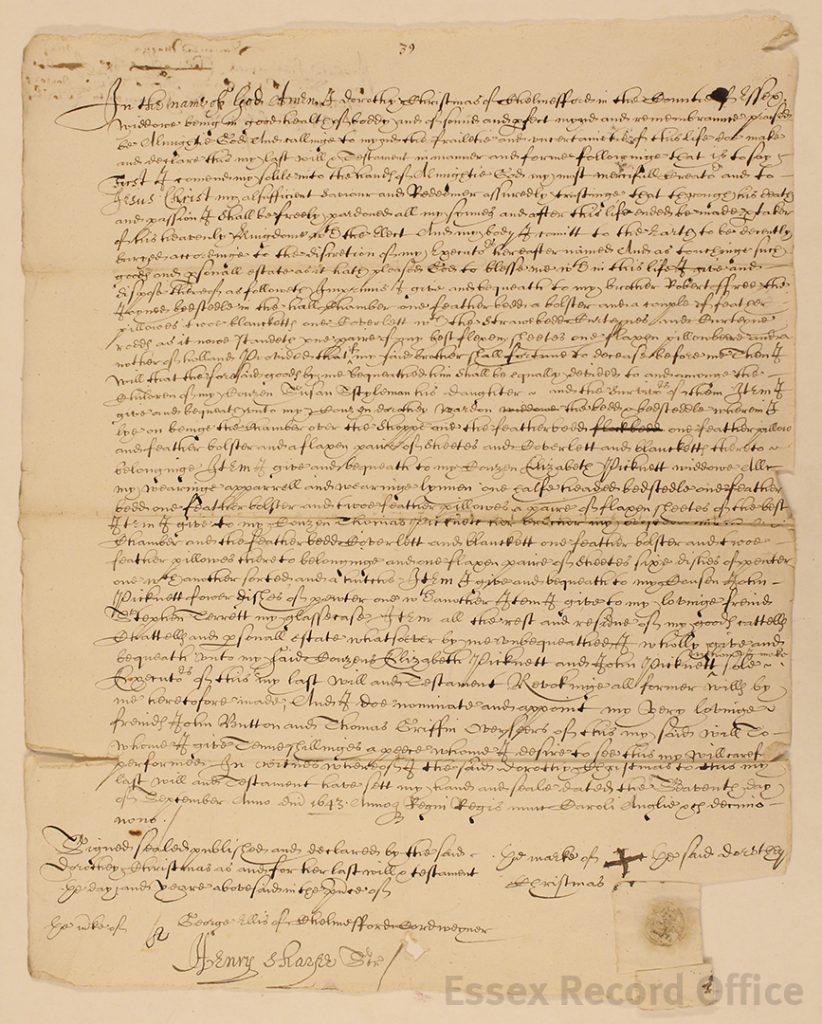

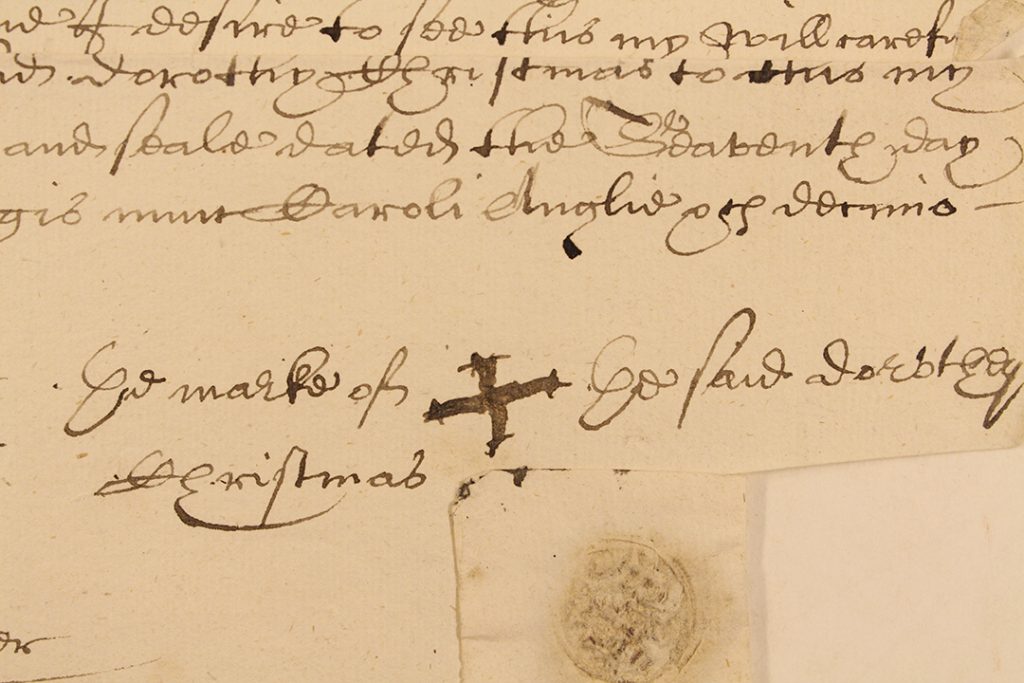

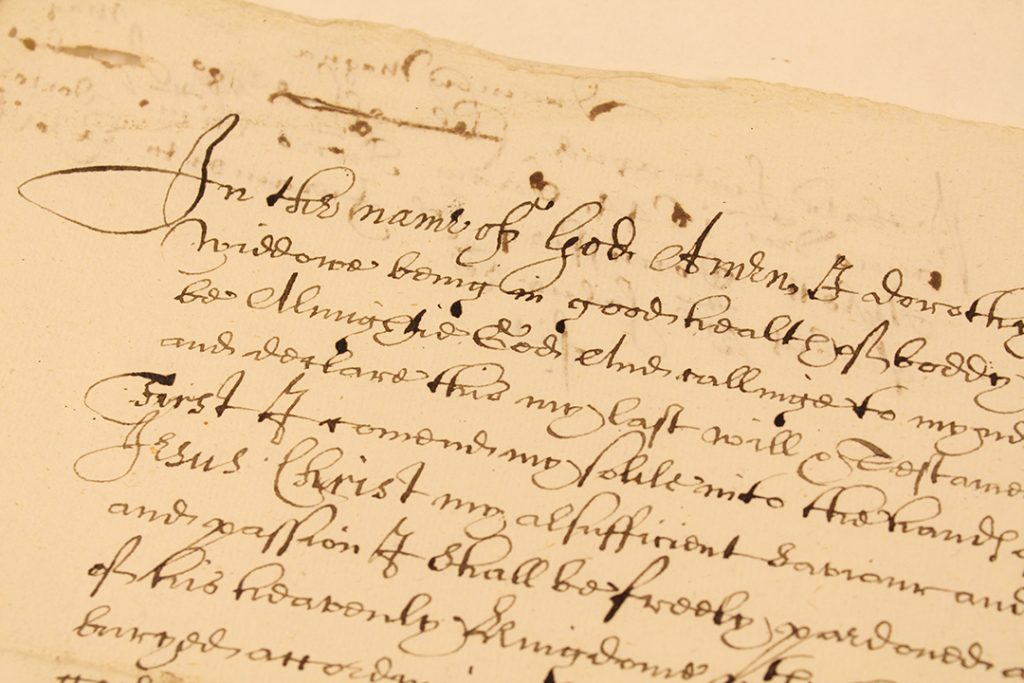

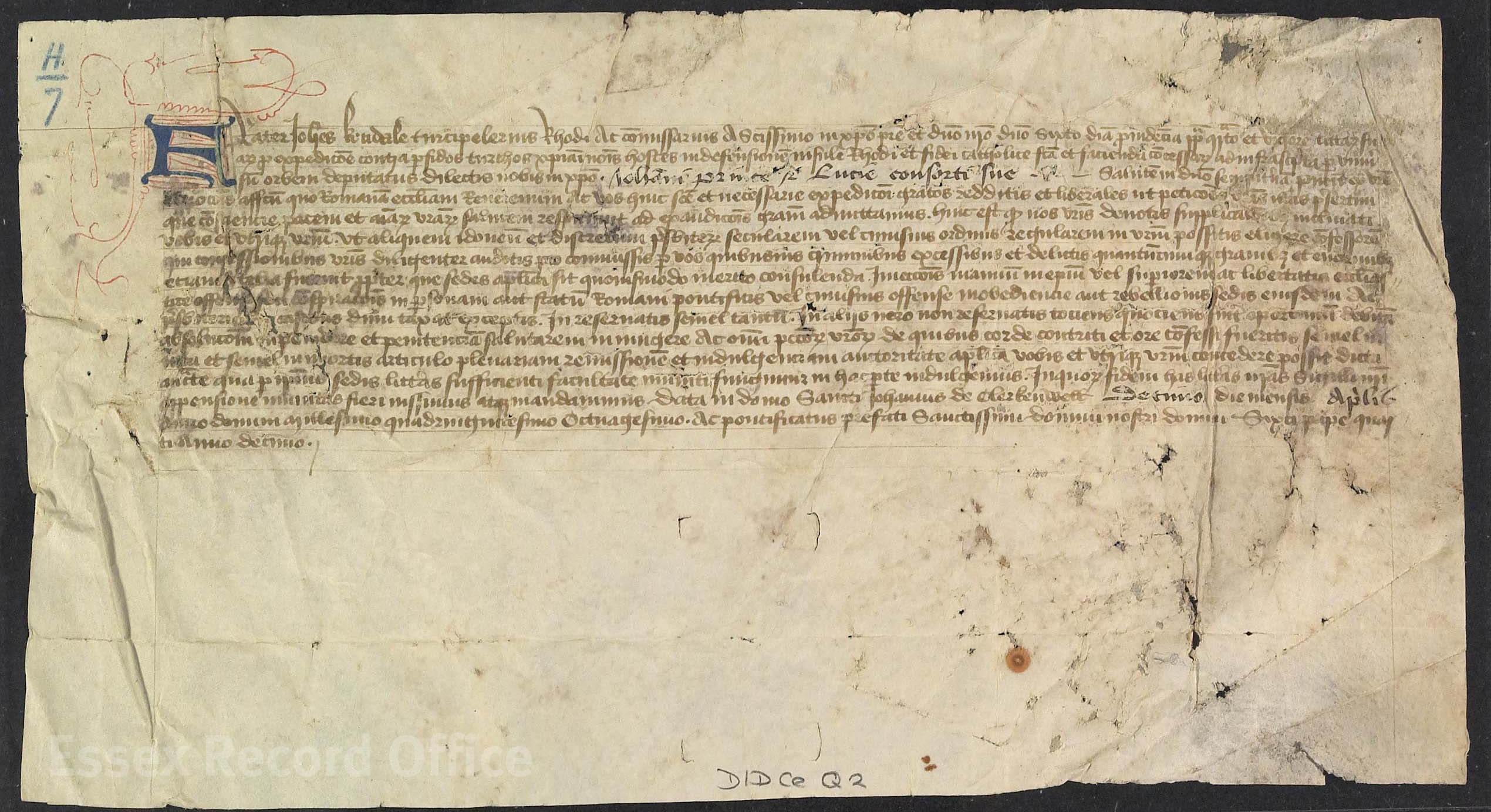

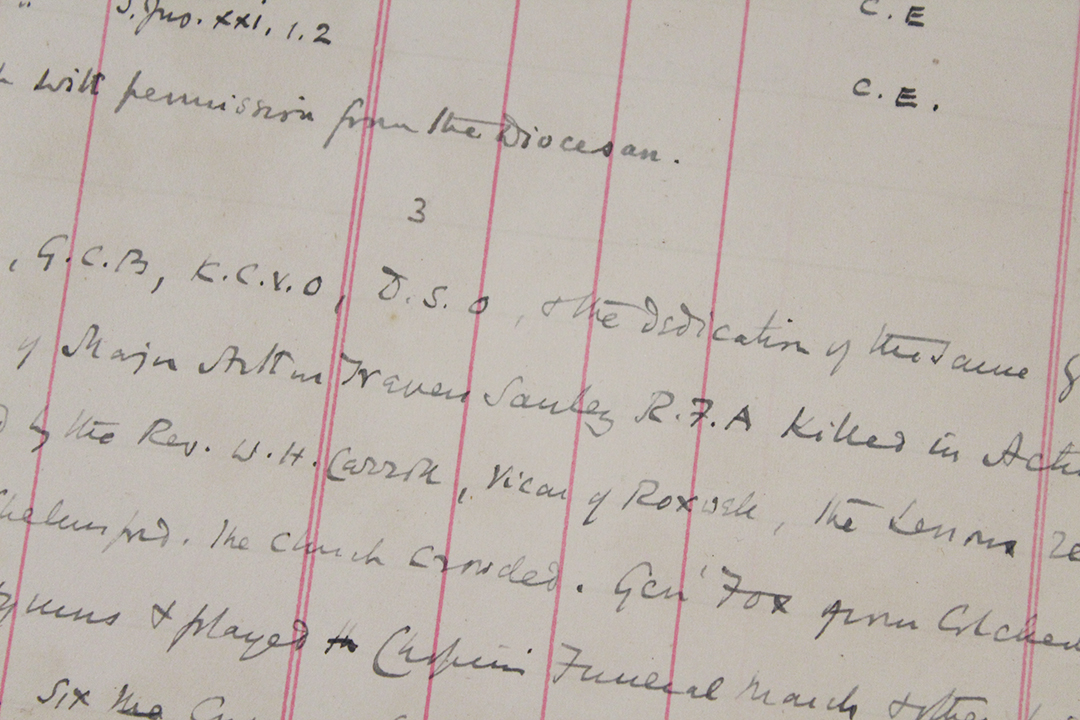

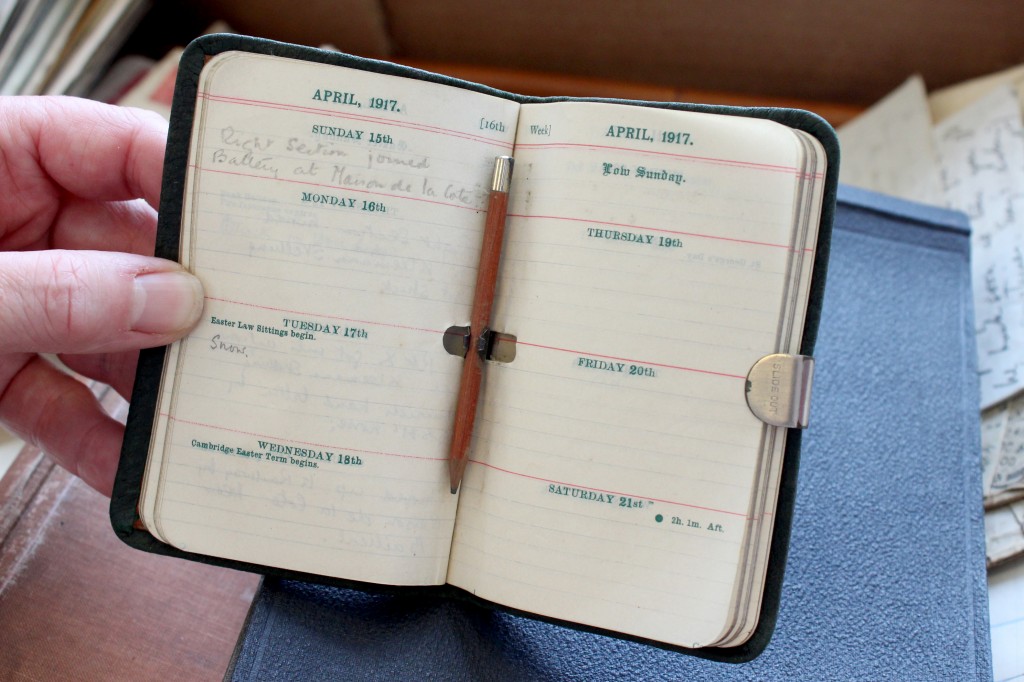

Their middle son, Arthur Travers Saulez, was a major in the Royal Field Artillery and mentioned twice in Dispatches, before he was killed at the Battle of Arras on 22 April 1917. This service register for St Christopher’s, Willingale Doe,(D/P 338/1/14) shows that almost exactly one year later at 3.15pm on 22nd April 1918 a window in the church was unveiled in his honour, erected by the officers, NCOs and men of his Battery. The Illustrated London News of 8th June 1918 mentioned that it was the first representation of a man in khaki in stained glass.

The entry in the register notes that the church was crowded, and that ‘The band of the Royal Artillery accompanied the Hymns & played the Chopin Funeral March and other pieces. 2 Buglers played the Last Post.’

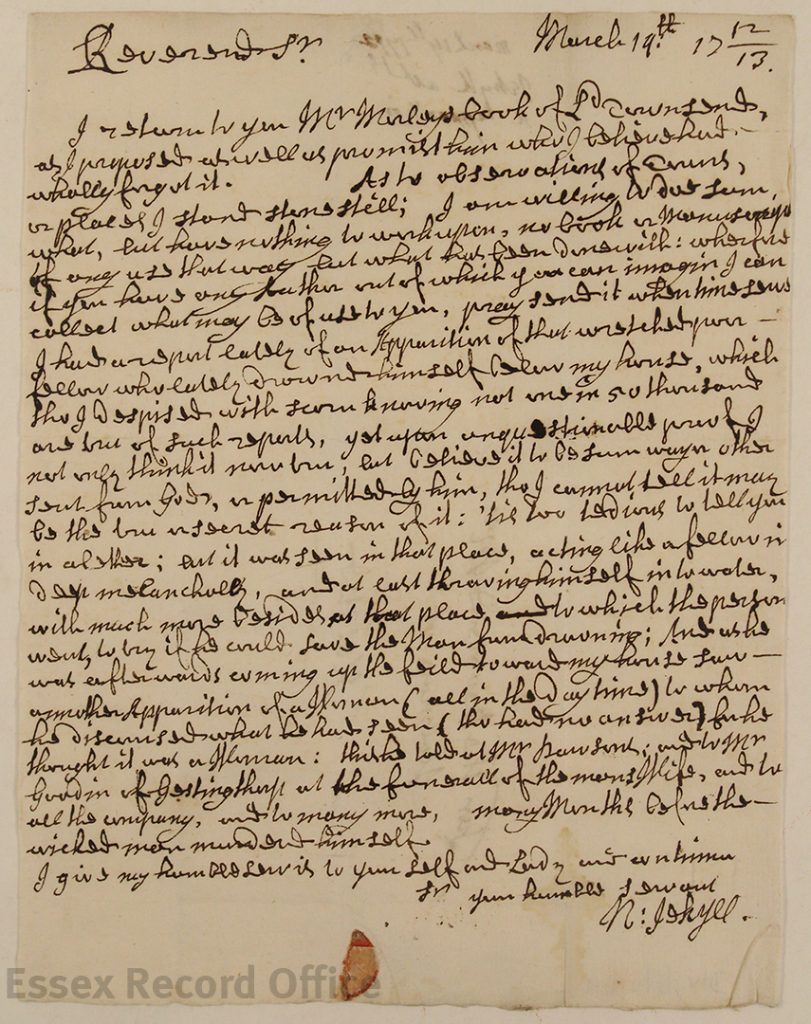

This entry from the service register for St Christopher’s, Willingale Doe, records a service to unveil a window in memorial to Major Arthur Travers Saulez on 22 April 1918, a year after he was killed in the Battle of Arras. Arthur’s father, Revd. Robert Travers Saulez, was the parish’s rector.

Memorial window to Arthur Travers Saulez at St Christopher’s church, Willingale Doe. It was reported at the time to be the first image of a man in khaki military uniform made in stained glass. Image by Paul HP on Flickr.

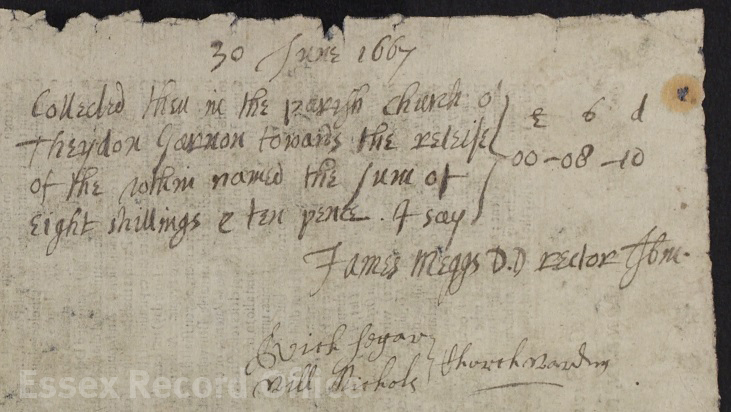

Arthur Saulez’s diary, with a pencil still in place at the week he was killed in April 1917

Arthur Saulez was aged 33 at the time of his death. His younger brother, Alfred Gordon Saulez, died in Baghdad while serving with the Army Service Corps in 1921, aged 35.

The Saulez brothers had maintained a correspondence with family members back home during the war and these form part of a collection held at ERO (D/DU 2948). We are grateful to the Friends of Historic Essex for acquiring the Saulez collection as part of the Essex Great War Archive Project and for subsequently paying for the cataloguing, conservation and storage of the letters. If you wish to find out more about this charity that supports the Essex Record Office please see their website.