An Essex Record Office project to preserve the history and memories of former Marconi Company employees is to receive a grant of almost £100,000 from The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

Part of Essex 2020, the project, Communicating Connections: Sharing the heritage of the Marconi Company’s wireless world, is to receive £93,000 from The National Lottery Heritage Fund. Further funding has come from Chelmsford City Council’s Essex 2020 fund and the Friends of Historic Essex.

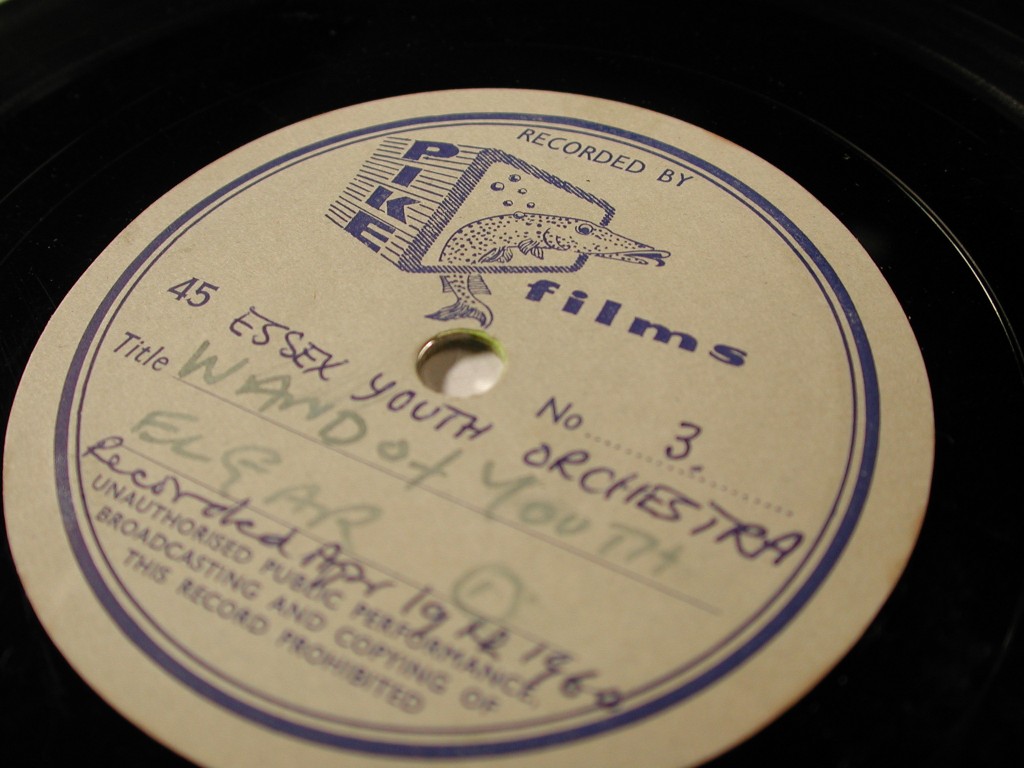

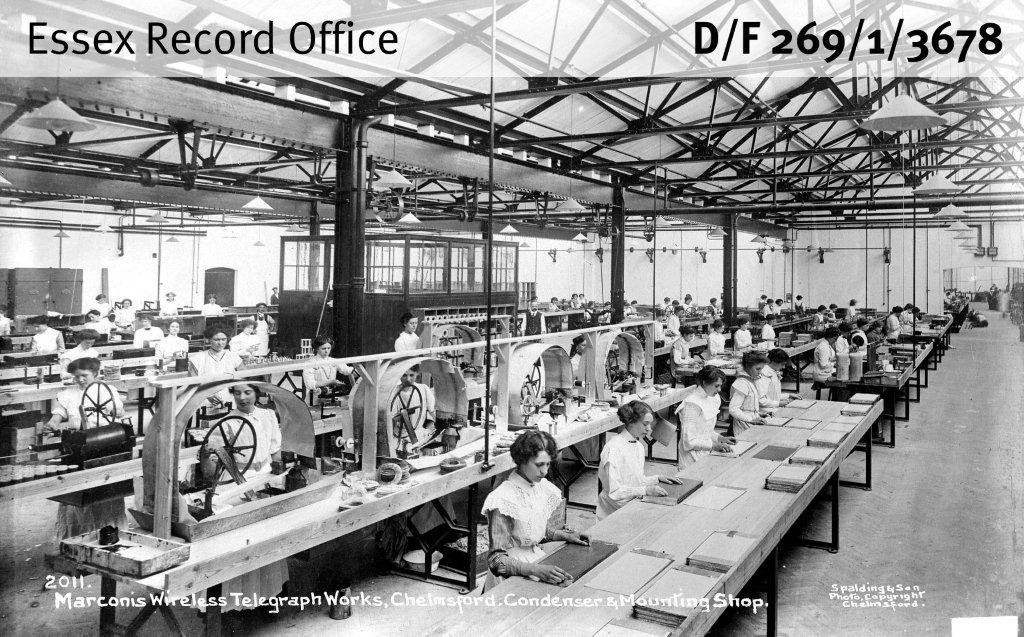

Communicating Connections aims to preserve the memories of former employees and others involved with Marconi through oral history interviews recorded by volunteers. Founded by Guglielmo Marconi, the company is famous for making the first ever transatlantic wireless communication, which was received in Newfoundland, Canada. The company also made the first wireless entertainment broadcast in the UK (renowned opera singer Dame Nellie Melba performing on 15 June 1920), and its equipment was vital for communication systems at sea, allowing the rescue of hundreds of people from the RMS Titanic and the RMS Lusitania.

“To receive such a large grant from The National Lottery Heritage Fund is absolutely wonderful. This project will not only allow us to celebrate the rich history of the Marconi Company and its historical connections with Chelmsford but it will also provide an informative and educational experience for all of our residents and visitors.”

Cllr Susan Barker, Essex county council cabinet member for customer, communities, culture and corporate

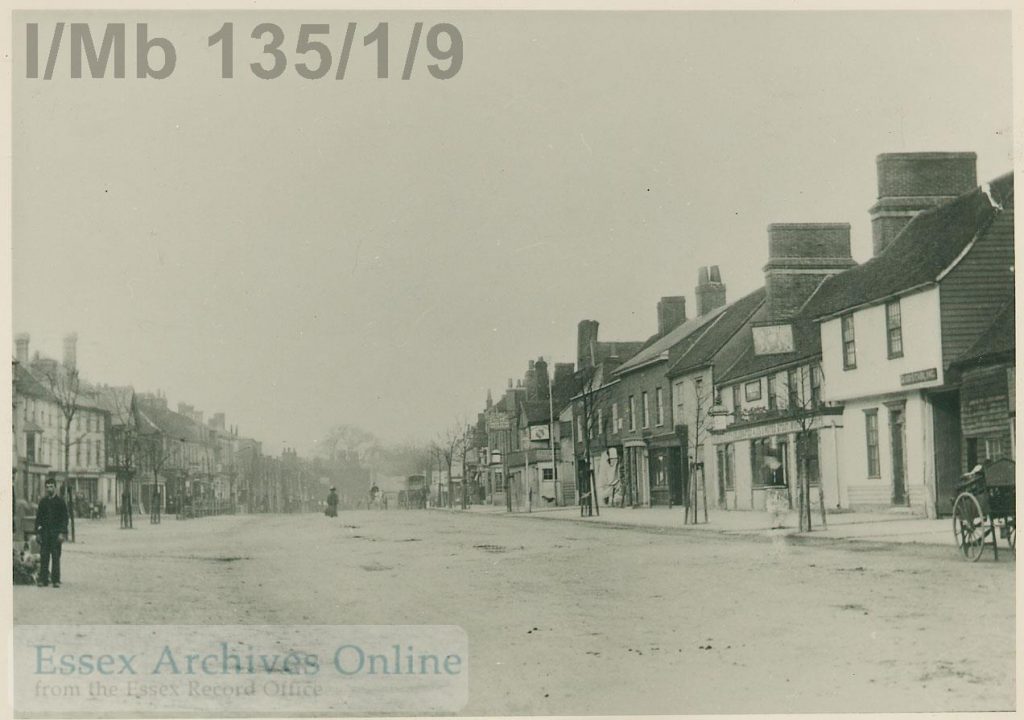

Local residents and visitors will be able to learn more about Marconi, and the company’s connections to Chelmsford, via an audio trail app, while a selection from over 150,000 images at ERO and Chelmsford Museums will be digitised and made available to the public to go alongside the oral history interviews. Temporary exhibitions featuring the interviews and images will be held in the city centre and will be co-curated by a team of dedicated volunteers, with guidance from Chelmsford Museums.

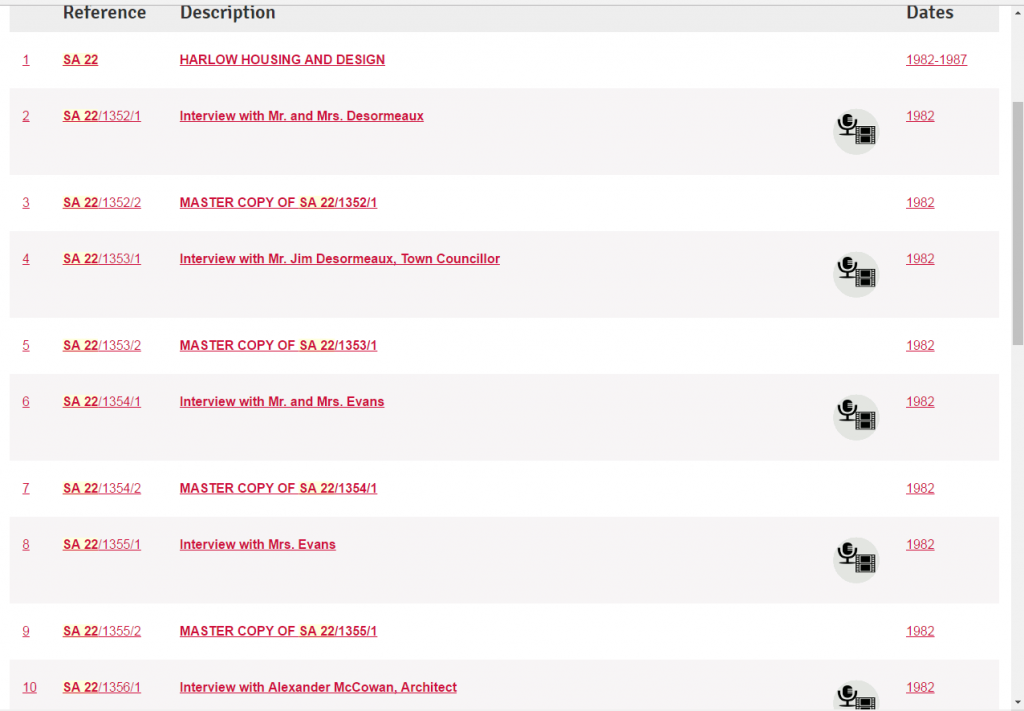

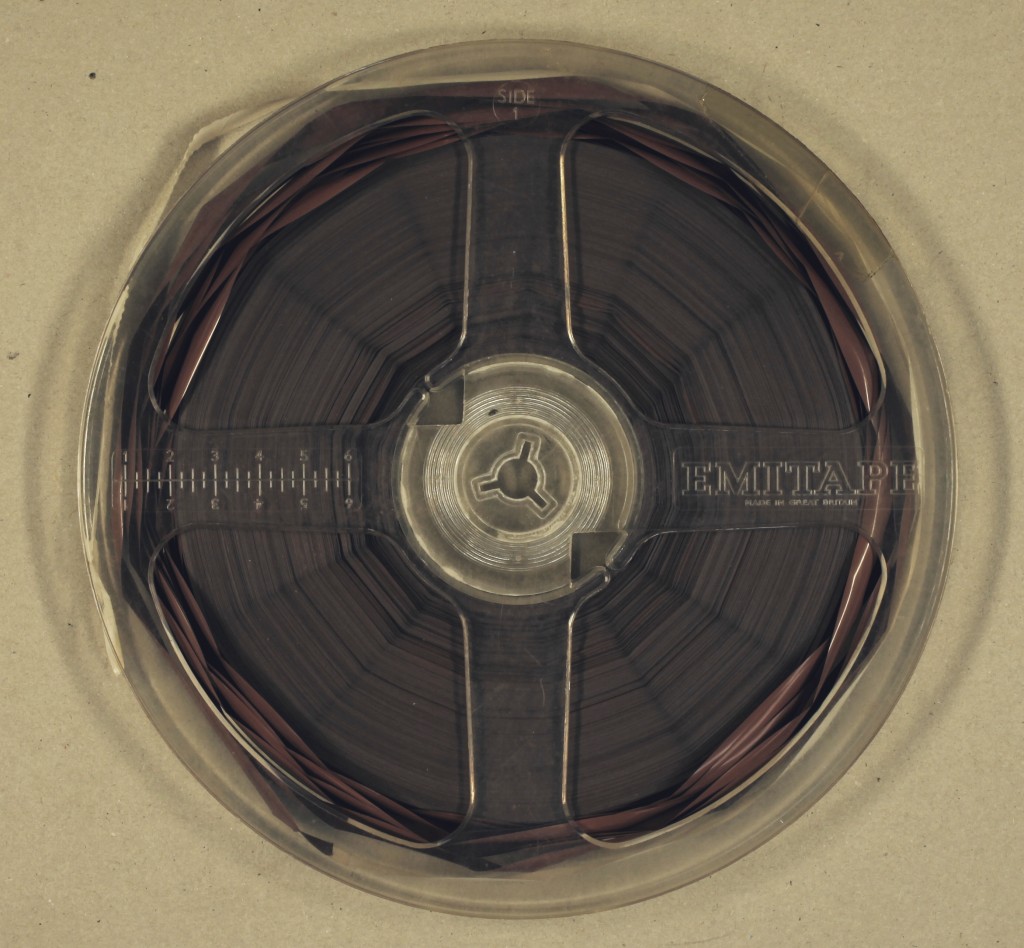

The project will also give us the opportunity to make better use of existing material about the Marconi Company, such as this interview with Gerald Isted, who started working for the Company in 1923 (SA 24/825/1).

Gerald Isted recalls his work at Marconi from 1923; work at New Street assembly shop; wages (SA 24/825/1 Side B Part 5)

Richard Anderson, Archive and Collections Lead at ERO, commented: “We are delighted with the grant from The National Lottery Heritage Fund as it will allow us to raise awareness of the Marconi Company and its links to Chelmsford’s heritage and history. We’re extremely grateful to the Marconi Veterans Association, Chelmsford Civic Society, the Chelmsford Science and Engineering Society, as well as Chelmsford Museums, for their help in developing the project, and to Teledyne e2V as they are directly linked to Marconi and have input into this unique industrial heritage.”

“Chelmsford City Museum are proud to partner with the Essex Record Office on the project. It fits perfectly with our mission to inspire residents and visitors to discover and explore Chelmsford’s stories through shared experiences. In this centenary year, it offers a landmark opportunity to foster the sense of civic pride local people have in our Marconi heritage and demonstrate how this legacy continues to influence our lives today.”

Dr Mark curteis, assistant museums manager at chelmsford city museum

“The archive is such an important local and national resource, as well as a great example of local science and creativity. Our Essex2020 funding panel were keen to support ERO’s ambition to make the archive accessible in new and creative ways. The panel were particularly supportive of the engagement of volunteers in the project and saw it as a strength that their voices and experiences would be represented.”

dr katie deverell, cultural partnerships manager at chelmsford city council and co-ordinator of chelmsford’s essex 2020 hub

Although the original project timetable is being delayed and altered due to COVID-19, keep an eye out for further announcements including opportunities to get involved with the project.

In the meantime, you can explore the world of Marconi through other Essex 2020 activities, including a virtual exhibition from Chelmsford Museum.