Frequently over the last several months commentators have compared living through the COVID-19 pandemic to life on the Home Front in the Second World War. Is that a valid comparison? What was it really like to live through that major event? Thankfully, there are still some people who remember those years and can share their stories with us.

Southend Achievement Through Football (ATF) is an organisation dedicated to changing lives through football, especially the lives of young people at risk of exclusion. By participation in sports and other recreational activities, young people develop skills and capacities to mature into individuals and members of society. But they do not just stop at sport. ATF also helps young people develop their sense of self by finding out about their heritage.

Building on the successful Heroes and Villains project, which allowed young people to explore the stories of individuals from Southend’s past, further funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund has allowed Southend ATF to encourage young people to hear the stories of residents in local sheltered accommodation. After training provided by ERO, Southend ATF interviewed 18 people specifically about their memories of the Second World War.

The participants ranged in age, from those who were still children in the 1940s, to those who were old enough to fight or serve the war effort in some other way. Thus the collection contains multiple perspectives, with different levels of understanding about current events, and different levels of impact experienced. Many of the participants grew up in London and were therefore prey to the Blitz and the stresses and strains that caused. Some were evacuated, some stayed at home. Some had family members who served in the military, some lost loved ones either at home or abroad, and some came through the ordeal relatively unscathed. Therefore there is no one common experience of what living through the War was like: it depended on personal circumstances.

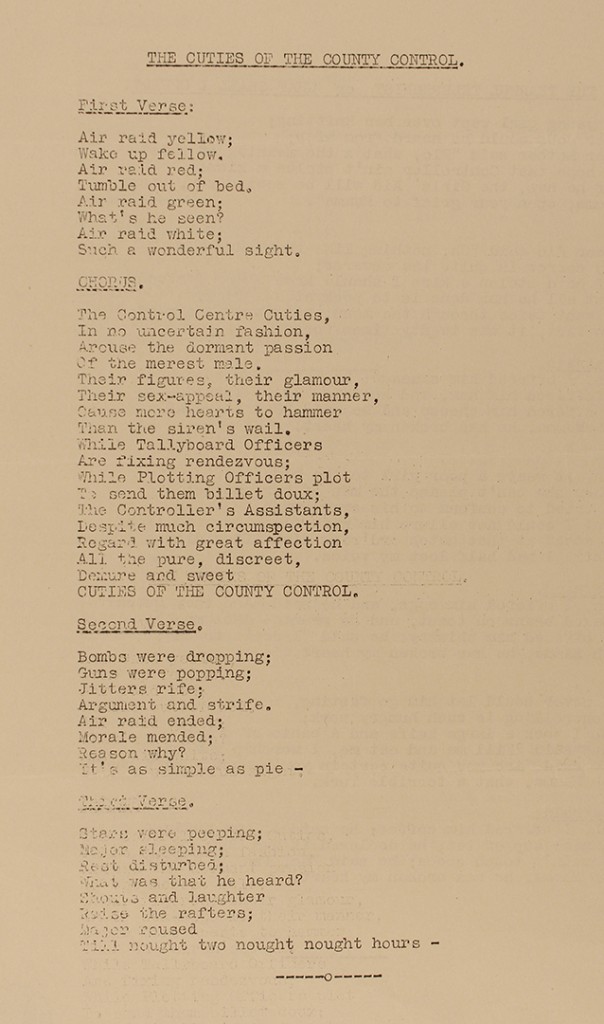

For instance, the extent to which people’s lives were disrupted by air raids depended on where they were living. Robbie spent much of the War as a Land Army girl, posted to a farm outside Witham to help keep the country’s agriculture growing and fill the gaps of men sent overseas to fight.

While all the rural residents had air raid shelters, she found them unnecessary overkill in those quieter areas.

‘We [the Land Army girls] never used it, only the country people used it – they thought they were in the thick of the war, you know, and nothing ever happened.’

The difference between life in London and life outside hit home on a day trip she took to the capital early in the War, when she first saw the scale of the devastation caused by intense enemy bombing.

This heavy fire seriously affected Johnnie, who was living near the docks in East London, with repercussions lasting into his adulthood, anxieties that resurrect during fire alarms. He recalled 68 nights of constant bombing in 1940. The mental and emotional strains could be as grave as physical injuries.

‘Each night… you just wondered, is this gonna be your last night? And you never knew…. You never get over what you went through, even though all those years ago…. In fact I still have, now and again, flashbacks as to, you know, what was going on.’

The experience of evacuation varied widely too. Some people used family connections to send their children to places of safety, and these generally resulted in happier experiences. For example, Norman stayed with his grandmother in South Wales, and found life in that peaceful village so idyllic that he initially refused to return to London when his father came to collect him.

Suddenly being sent to live with strangers was a very different matter. Even for those who stayed with their siblings, it was difficult: getting used to the rural way of life, feeling conscious of imposing on the family’s space and resources, and experiencing animosity from local children. But sometimes even being evacuated with strangers could turn into a happy occasion. Joan enjoyed her experiences living on the edges of the Longleat Estate so much that she frequently returned to the area for holidays in adulthood. As she was only six or seven years old when she was sent away, she came to see her evacuee family as her adopted parents, and didn’t even recognise her mother when she finally returned to her birth family five years later. ‘Home’ was a word of shifting meanings, and it could be difficult to adjust.

However, there are common trends evident among the interviews. While the impact of rationing varied from family to family, largely dependant on how much families could grow for themselves, all participants recalled the need to ‘make do and mend’ to some extent. There was no waste, and parents had to be resourceful to acquire sufficient food and clothing for their families. While treats were limited, this made them more treasured, as some interviewees presented very vivid, detailed memories of eating their weekly sweets ration.

Another common theme is that children still found ways to play. Sometimes their normal play spaces were converted to fields of war, such as the parts of the beaches around Southend, which were fenced off both due to defences against potential invaders and to protect residents from possible mines dropped by enemy aircraft. Instead, children turned scenes of devastation into playgrounds, exploring bomb sites and collecting shrapnel to trade like marbles or Top Trumps cards. The interviewees’ experiences prove that even in the midst of great upheaval, children have a knack for play, a facet of their lives so important that the right to play is one of the rights for all children enshrined in the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Finally, most participants commented on the sense of relief when celebrating VE Day, Victory in Europe Day, on 8 May 1945.

Although the War was not yet over, with fighting continuing against Japan until August, VE Day marked the start of the end: no more fear of bombs, no more disrupted nights of dashing into air raid shelters. But life did not return to normality straight away. Rationing continued into the 1950s. Servicemen returned home only gradually – Fred, who served in the Army, describes long periods of time spent in Germany and Italy after VE Day, just waiting to be sent home. He was not demobilised until 1947. And the war changed people irreversibly, meaning life could never again be the same.

Four of the interviews took place after lockdown (recorded outside, observing safe distances). These presented an opportunity to ask for comparisons directly from survivors of the Second World War, seeking reflection on how that ordeal compared to living through the COVID-19 pandemic. We will let their observations stand for themselves, without further comment or interpretation:

Essex Record Office · Comparing the Second World War to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Many thanks go to the participants who shared their remarkable stories for future generations to learn from, and to Southend ATF for taking the time to record these precious, unique stories and then share them with ERO for others to listen and enjoy.

You can listen to themed compilations of clips from all the interviews on our SoundCloud channel.

Or you can find out more about accessing the whole collection on Essex Archives Online (Acc. SA892).