Today at ERO, we welcomed a number of High Sheriffs of Essex, past and present, to a reception hosted by Cllr Kay Twitchen, Chairman of Essex County Council, to mark the deposit of a unique set of records.

Would you like to know where to find a trumpeter, or how much it costs to put on a good garden party, or how to deal with a really cold judge? These and other more serious questions will soon have better answers thanks to the High Sheriffs of Essex.

When asked to think of a sheriff, our mental picture library might supply a greedy, grasping figure (possibly played by Alan Rickman), predictably defeated by the rather less interesting forces of goodness and virtue. Beyond that, usually, nothing. Considering that with the exception of the Crown itself the shrievalty is the oldest public office in England, this is a pity, but it is about to become less true.

The post of High Sheriff dates back to before the Norman Conquest. The origins of the post are in Saxon times – the title of ‘reeve’ was used for senior officers with local responsibility to the king within the shire, and over time ‘shire reeve’ became ‘sheriff’.

In Anglo-Saxon England the sheriff was responsible for the maintenance of law and order through the system of tithings, groups of approximately 10 men who were bound together in mutual assurance. All able-bodied men aged 12-60 had to belong to a tithing, and each man in the group was responsible for the good behaviour of each of the others. They were bound to observe and uphold the law; if a member of tithing broke the law then the others were obliged to report the culprit and deliver him to the constable, failure to do this would result in everybody in the tithing being fined. The sheriff was responsible for inspecting the tithings (although after the Norman Conquest many lords of the manor acquired the right to do this for themselves).

Under the Norman regime the sheriff was the means of enforcing (literally) the King’s writ in the localities, with the authority to summon the posse comitatus (county force or power) to help maintain law and order. The sheriff discovered criminals and delivered them to the royal courts for judgement and executed writs issued by the Crown. In addition the sheriff supervised Crown lands in the county and handed over the revenue to the Exchequer and he could also compulsorily requisition food and supplies for the King (e.g. to fight war). With no oversight from central government, these powers could give the sheriff opportunities for extortion and corruption (hence the Sheriff of Nottingham).

The sheriff also presided over the shire court (the shire courts along with the hundred courts are thought to be one of the means by which Domesday Book was compiled in 1086). From the mid-13th century knights of the shire were elected in the shire court to sit in Parliament and coroners were also elected there. The last duties of the shire court only passed to county courts in 1886 with the County Courts Act.

The medieval sheriffs were also over-burdened with routine business (they have been described as ‘workhorses’ of medieval local government) which meant that law enforcement could be patchy and on occasions arbitrary. As early as 1327 ‘good and lawful men’ were appointed in every county to ‘guard the peace’, called conservators or wardens of the peace and in 1361 justices of the peace were created. In the 1540s lord lieutenants were appointed to take over the military duties of the sheriff.

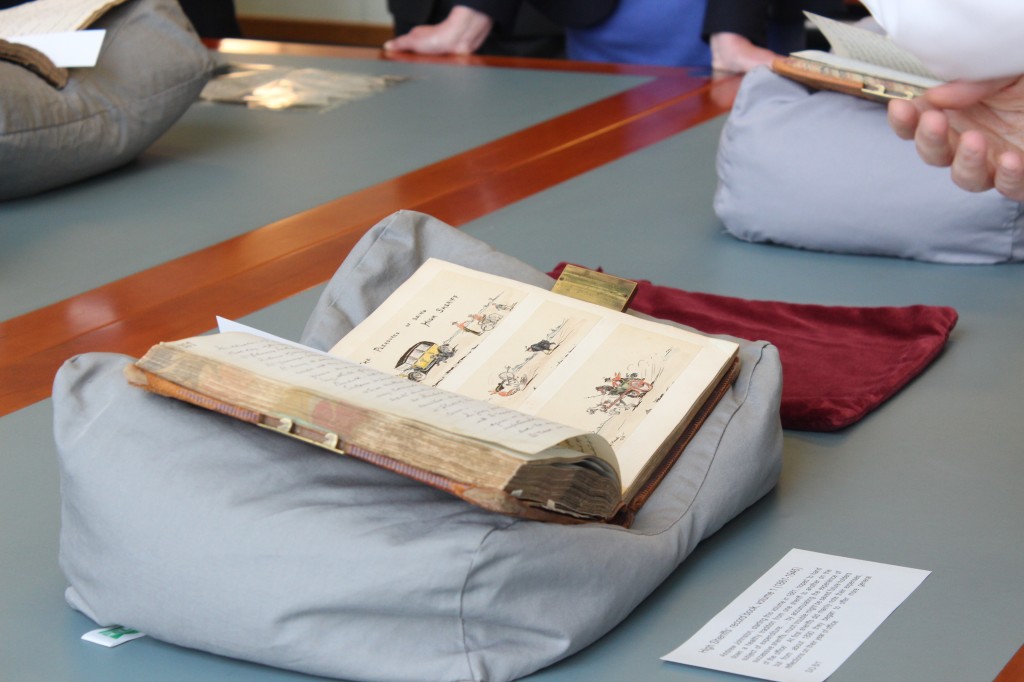

By 1881 when the High Sheriffs of Essex started to keep the record books which are being deposited with ERO, they had long given up persecuting peasants. Their real powers and duties were, in fact, quite limited. This makes their later history a fascinating parallel to that of the monarchy itself: an exercise in finding new roles, while still keeping up appearances. This was not always easy.

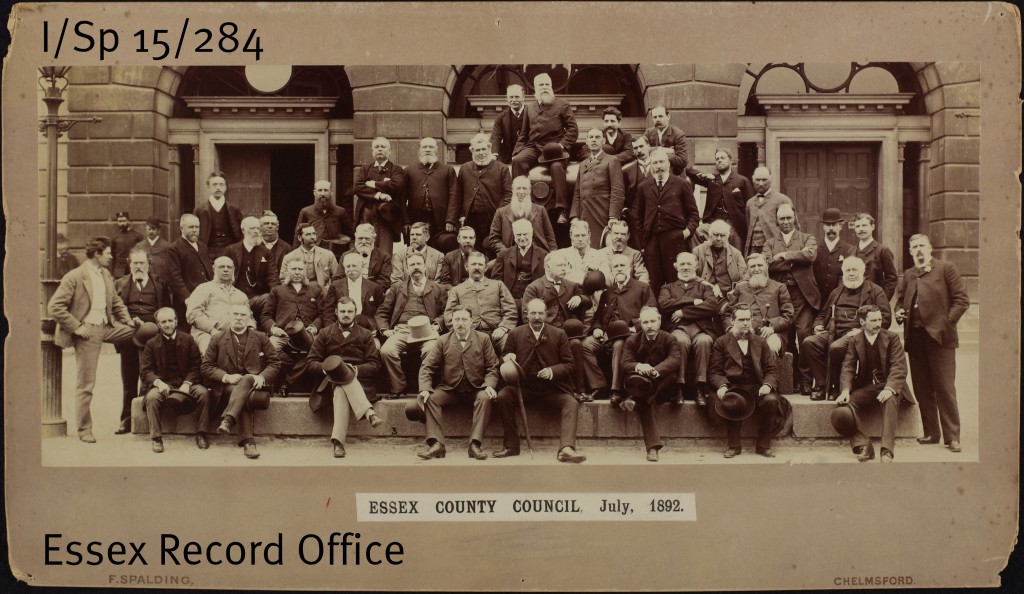

Essex County Council, 1892. Andrew Johnston, the Council’s first Chairman and the High Sheriff who began the journals, is in the top centre of the photograph, sitting aside the cannon which used to be outside Chelmsford’s Shire Hall

At first they were concerned especially with the expenses of an un-salaried office set about by all sorts of costly ceremonies (hence the trumpeters, part of the formal escort provided by the sheriffs for the assize judges when they visited Chelmsford). From about 1890, however, sheriffs started to write more general reflections on their year of office. In 1916 one sheriff’s car broke down on the way to the assizes, leaving him and his chaplain to complete their journey to Chelmsford ‘in an open hawker’s cart’. In 1959, when the hot water system at the judges’ lodgings failed during the Winter Assizes, the High Sheriff ‘nearly had [his] neck wrung’, the judges threatened to leave for London forthwith, and the sheriff ended up having to stoke the boiler himself.

Even so, during the 20th century the sheriffs were able to simplify many of their office’s remaining ceremonial duties and to develop a new social role. Today’s High Sheriffs continue to attend on visiting High Court judges, and, together with the Lords Lieutenant, to act more generally as the Crown’s local representatives, especially, in their case, in areas of crime and punishment. They also work to promote the voluntary sector. A mainly symbolic role, maybe, but who says that symbols are not important?